A

Missio-Relational Reading of Romans:

A

Complementary Study to Current Approaches [1]

Enoch Wan

Published in www.GlobalMissiology.org “Relational Study” April 1, 2010.

Originally published as “A Missio-Relational Reading of Romans” in Occasional Bulletin, EMS, Vol. 23 No. 1, Winter 2010:1-8

ABSTRACT:

As

a complement to current approaches to the study of Romans, this paper employs a

missio-relational reading of the Epistle to Romans. Missional and relational aspects are highlighted as well as

the community

orientation (instead of individualistic orientation) of selected passages and

themes in Romans.

INTRODUCTION

As

a complement to current critical approaches to the study of Romans (e.g.

historical-critical, doctrinal, etc.), this study attempts to read the epistle in

a missio-relational manner. This

approach will highlight the missional focus and relational aspect of selected

passages and themes in Romans, paying particular attention to the community

orientation (instead of individualistic orientation).

Romans

is an occasional letter written by Paul, a Jew of second Temple Judaism[2]

and the apostle to the gentiles.

Paul wrote Romans in order to address certain internal concerns within

the Christian community in Rome, and to introduce himself to them in

anticipation of a later mission trip to Spain.

Even

though Paul had a specific, historical reason for writing this letter to the

Christians in Rome, it still contains missional and relational elements that

can be applied to the contemporary context of post-modern and post-Christian

western society.

The methodology of this

study is a missio-relational approach as compared to the regular practice of

doctrinal-rationalist approach. This is a sequel to earlier works on

“relationality” (Wan 2006a), “relational realism paradigm” (Wan 2006b) and

“relational theology and missiology” (Wan 2007).

A MISSIOLOGICAL READING OF ROMANS

There is no question that Romans was considered a very

significant book of the Bible at the time of the Reformation; this is especially

true for the doctrine of “justification by faith.” However, text covering the doctrinal topic of “justification

by faith” is found for the most part only in Romans 3:21-5:21. Taken as a whole, the book of Romans is

more missional in nature.

The

beginning and conclusion of Romans contain a consistent emphasis on “obedience

to the faith among all nations”[3]

(by apostolic duty, 1:5, and by the prophetic scriptures, 16:26). Paul had a

strong motivation “to win the Gentiles” (Rom 15:15-16) and a strong desire to

push on to new frontiers beyond Rome to Spain (Rom 15:19-20, 23-24, 28).

Peter T. O’Brien

had proposed that from Rom 15:14-33 alone he could identify six “distinguishing

marks” of Paul’s missionary activity.[4]

Similarly, Steve Strauss (2003) formulated five significant principles for

missions strategy from Rom 15:14-33. Dean S. Gilliand (1983) extensively examined

the missiological dimension of Romans.

The missiological focus

of Romans is “the gospel”

In

Romans, Paul articulated well his understanding

of the truth of the gospel

and grace.[5]

The main theme of Romans is “the gospel” with Romans 1:16 as the theme verse.

The “message of missions” in Romans in the “prologue” is itemized below in terms

of “the gospel” motif:

Š

The theme is

“gospel” which is called “the gospel of Christ” (1:16)

Š

It is also

called “the gospel of God” (1:1)

Š

It is also

called “the gospel of his Son” (1:9)

Š

The effect of

the “gospel” - “it is the power of

God unto salvation” (1:16)

Š

The target of

the “gospel” is “every one that believes” (1:16)

Š

The gospel

manifested - “the righteousness of God revealed from faith to faith”(1:17)

Š

The missional

sequence of the gospel[6]

is “to the Jew first, and also to the Greek” (1:16)

A missiological reading of

Romans can be supported by the motif of “the Gospel” and

can be thematically

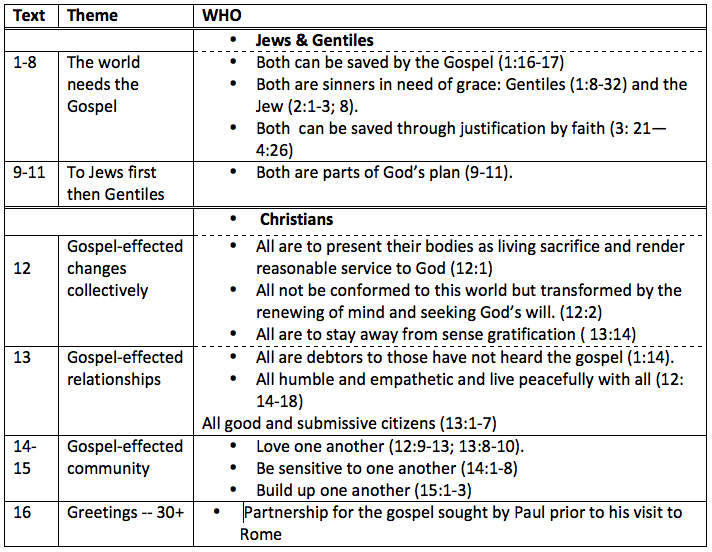

diagramed, as shown below:

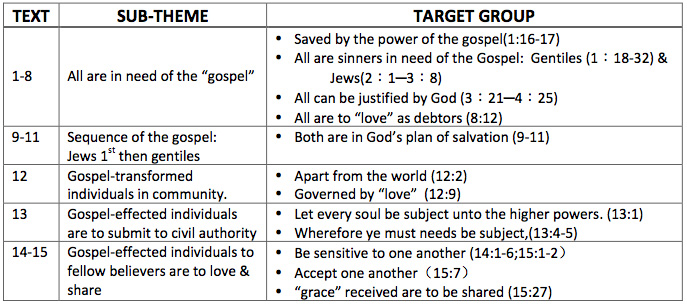

Figure 1 — “The Gospel” - Thematic diagram of

Romans (Wan 2005:1)

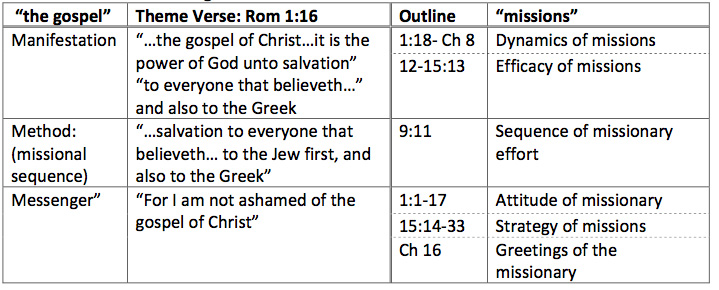

A

missiological reading of Romans can also be supported by a thematic diagram of

“missions” as shown below:

Figure 2 — “Missions” - Thematic diagram of Romans

In Figure 3 below, Romans is outlined in terms of double motifs: “the gospel” and “missions.”

Figure 3 — Outline of Romans with Double

Motifs

Paul’s missionary

identity in Romans

Paul’s

self identity is the apostle called to be the bearer of the gospel (Rom 1:1).

He is the messenger of missions specifically called

and separated unto the gospel of God. With the constant gratitude of a forgiven

debtor (1:14) and with endurance and hope (5:1-5), the blessed servant reached

out with the gospel message and was empowered by the Holy Spirit.

Paul had two elements in his personal mission

policy as shown in Romans: (Wan

2005:2)

1:16 “For I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ: for it is the power of God unto

salvation

to every one that believeth; to the Jew first, and also to the Greek.”

15:20 “Yea, so have I

strived to preach the gospel, not where Christ was named, lest I

should

build upon another man's foundation.”

The first element of

Paul’s personal mission policy is sequentially first to the Jews then gentiles.

Paul’s mission strategy was made clear in the missional sequence of “to the Jew

first, and also to the Greek” (1:16; 2:9-11). This strategy was also

exemplified in his personal efforts (Acts 9: 20-22). In his first itinerary

mission trip (Acts 13:5, 14, 42; 14:1; 15:21), Paul was resisted, slandered and

persecuted (Acts 13:44-49) and even stoned (Acts 14:19). He announced that he would turn to the

gentiles (Acts 13:46-49). However, again he returned to the Jewish synagogues

on his second itinerary trip (Acts 17:1, 10, 13; 18:4-5, 19). Even on his third

mission trip (Acts 18: 26; 19:8, 17), Paul continued preaching “to the Jews

first, and also to the Greek.” This consistent mission strategy and personal

policy is expounded in great detail in Romans 9 to 11.

The power of the gospel is well demonstrated by

Paul’s experience of repentance and

salvation, mentioned repeatedly in his letters (Eph. 3:1-13; 1 Cor.

15:9-11; 1 Tim. 1:12-17). In

Romans, he points out that all men have sinned, but all have access to God’s

grace through faith (Rom. 3:21-31; 5:1-2; 21), regardless of whether they are

Jews or Gentiles. Paul also emphatically declares the efficacy of the gospel as

universal (vv 3:21-31), but beginning with the Jews and expanded thereafter.

“Set apart as an

apostle for the Gentiles,” Paul made the will of God his priority, but not

without mission strategy and practical movements. According to the will of God,

Paul was “called [to be] an apostle, separated unto the gospel of God” yet he

made great efforts to preach the gospel. Although Paul was “the apostle of the

Gentiles”(11:13), as Gillian observes, “Paul never lost the vision for his own

people. He could not forget that the Messiah’s kingdom was intended primarily

for them” (Gillian 1983:30).

In Romans 1:3, Paul

notes that Jesus was a descendent of David. Paul was aggressive in reaching his kinsmen who resisted the

gospel. Moved by the Spirit and with the gratitude of a debtor, he endeavored

to proclaim the gospel to all nations (1:14-15; 9:1; 15:17-210. But his heart-felt passion for his

kinsmen was deep and solid (chapters 9-11), bringing them the gospel even at

the risk of his own life (15:31). (Wan 2005:3)

The second element

of Paul’s personal mission policy is to conduct pioneer work

without duplicating what others had done

(Rom. 15:20). Therefore his anticipated visit to Rome is very important to his

mission strategy. He desired to win the partnership with individuals and the

congregation in Rome (Rom. 15:22-29) for a westward movement based in the

capital, launching beyond Rome to Spain.

Rome, as

the capital of the Roman Empire, was the cultural, political and military

center of the time, therefore strategic for gospel outreach. The church in Rome

had grown (1:8, 13) with the potential to become the center of the western

church and the base for a westward expansion of the gospel. Roger E. Hedlund’s suggestion is

helpful, that Paul’s vision of mission was universal; yet his strategy was to

use urban centers (Strauss 2003:462-463) as his

missionary base. Rome as the capital was strategic to Paul’s missionary plan.[7]

Paul was motivated “to win obedience from the

Gentiles” (Rom. 15:15-16); therefore he was determined to launch out to new

frontiers (Rom. 15:20). He wanted the church in Rome to partner with him in his

missionary ministry westward (Rom. 15:25, 28-30). Paul’s ministry of preaching the gospel included “evangelism and church

planting…church nurturing” (Strauss 2003:463-464) and his ministry in the

eastern Mediterranean region was his way of “fulfilled the gospel” (Bowers

1987:186.) from Jerusalem to Illyricum (Rom 15:18-20).

The first

part of Romans (1:17-11:36) is Paul’s extensive exposition of the gospel that

will become the basis of its missio-relational application in the second part

(12-16). The following quotation

bears out this point clearly:

“So,

it is significant that he begins and ends his great missionary exposition of

the gospel (which he hopes to take to Spain and invites the church at Rome to

support him in doing so) with a summary of his life’s work as being aimed at

achieving “the obedience of faith among

all the nations.” (Wright 2006:527)

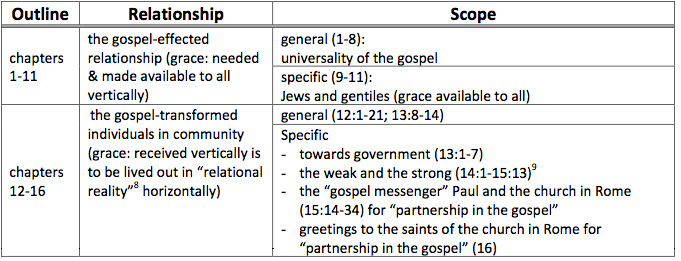

A RELATIONAL READING OF

ROMANS

This study uses the same framework of vertical and

horizontal relations modeled by Christopher J. H. Wright (2006:208-211), but

focusing on selected themes and texts in Romans. The theological understanding of Paul in Romans (i.e. the gospel,

salvation and grace) provides the basis for a relational reading of

Romans. With the aid of a “relational framework” (Wan 2006a, 2006b, 2007) and a

relational interpretation of “grace,” Romans can be divided into two major

sections:

Figure 4 –

Outlining Romans Relationally

Figure 5 illustrates this approach in Romans in

terms of “relational gospel,” i.e. a relational understanding of the gospel.

Figure 5

– Directional outline of Romans - “Relational Gospel”

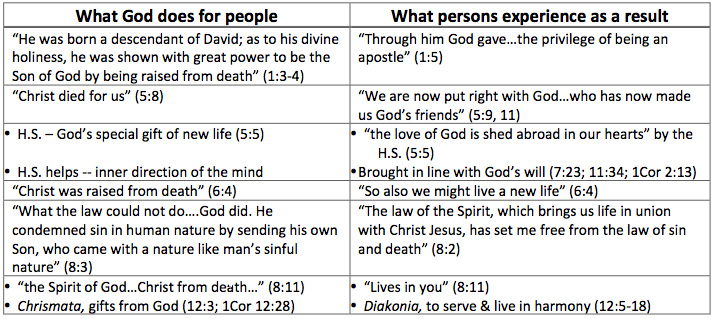

On the

point of “relational gospel,” Gilliand (1983:34-35) observes that there is a

“dual theme” in all of Paul’s epistles, “what God does for people and…how

people respond to the divine initiative.” The references in Romans are listed

below:

Figure 6

– Relational Gospel in Romans: Dual-directional Understanding[10]

The

“relational gospel” began with God’s grace vertically and it requires personal

faith vertically from believers “in Christ Jesus” (Rom 3:26, Gal 2:16). Faith is the way a believer expresses

his “total response to the love of God”[11] and God’s grace for sinners.

The key

concepts for salvation in Romans are all relational: “justification” (4:25;

5:16), “redemption” (Rom 3:24), “adoption” (8:23), “reconciliation” (5:10-11;

11:15) and “in Christ” (3:24; 8:1,2,39; 9:1; 12:5; 16:3,7,9,10). In Paul’s life and writings, “the heart

of the gospel will always be found to derive from the action of God, through

grace…” (Gilliand 1983:49).,

Paul sometimes

uses the word “justification” and “reconciliation” interchangeably, as

illustrated in Rom 5:9-10, “now justified by his blood” and “we were reconciled

to God by the death of his son.” “Justification” is a favorite term of scholars who are

“doctrinal and rationalist” inclined when studying Romans. Their emphasis is on

the “forensic” aspect of “justification” at the expense of the relational

dimension of the word. Martin (1981:37) is helpful in clarifying that

“justification” indicates broken interpersonal relationships that have now been

put right.

Relational reading of

Romans: prologue (1:1-17) and conclusion (chapter 16)

A simple

relational reading of the prologue of Romans (1:1-17) can be

listed below:

Š

Relational call: “called to be an apostle, separated unto the gospel

of God” (1:1)

Š

Relational gospel source: “promised by his prophets,” “of the

seed of David” (1:2-3)

Š

Relational gospel effect: “we

have received grace,” “I am …the gospel to you” (1:4-17)

Paul

defines his apostolic mission in Romans 1:5 and repeats it again in 16:26

(Wright

2006:247). The thematic verse for

Romans, 1:16, serves as a prelude to “Paul’s full exposition of the gospel” that

forms the framework for a relational reading of Romans. (Wright 2006:180, 208-215)

The

extensive personal greetings that conclude the book of Romans, chapter 16, can

best be explained in terms of Paul’s missionary strategy of “partnership of the

gospel” with individuals and churches in Rome (Rom 15:22-29). The personal

greetings in just Romans 16 is strikingly intentional and more extensive than

greetings found in all other Pauline epistles combined. (Wan 2005:2)

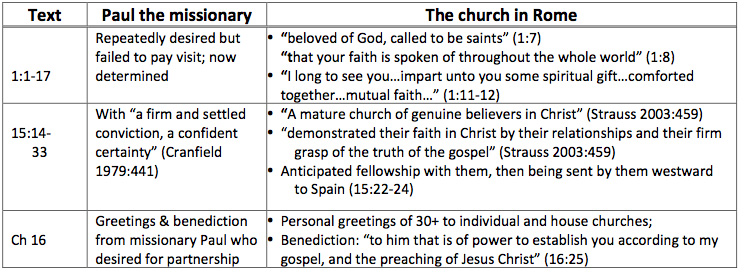

Relational reading of

Romans: gospel partnership of Paul and the Christians in Rome

When penning Romans, Paul had not visited

the church in Rome, located in the

capital of the Roman Empire and therefore strategic

in the plan of westward outreach of the gospel. Paul “purposed” to come to

Rome, but was not successful (1:8-13). So he wrote this letter to announce his

travel plans and to ask the believers there to pray for him (1:8-10). He

intended to get there after urgent business was properly handled (1:11-13), and

be sent to Spain from there (15:23, 28).

The figure below shows the horizontal relationship between Paul and the

churches in Rome.

Figure 7 — Horizontal

relationship: Apostle Paul and the Church in Rome

More than winning converts

and sharing spiritual blessings with those in Rome (Rom 1:11-13), the intention

of Paul’s systematic coverage of “gospel” and “grace” in Romans 1:18-15:13 was

to prepare “these believers in every way possible, especially in the right

belief, to rise to the challenge and become a missionary center (Rom 15:24,

28)” (Gilliand 1983:32)

Relational reading of

Romans: the gospel of reconciliation[12]

(Rom 5:10-11; 11:15) and the Lordship of Christ

One

form of the vertical relationship found in Romans is “reconciliation” between

the just God and fallen man. The gospel of reconciliation is a relational

reality as described by Gilliand (1983:25):

“Reconciliation that comes by the means of grace describes salvation in

its simplest terms. Men and women are brought into harmony with God through a

voluntary act on God’s part…”

Paul became a

changed person after his confrontation with the resurrected Lord who reconciled

the persecutor Saul to begin “a ministry that always took its message and

strength from the reality of a reconciling gospel.” (Gilliand 1983:29)

The Hellenistic

world of the Greek is full of their gods. The gospel of reconciliation takes on

a new meaning when viewed from a Hellenist perspective:

“The gospel is a

message of restored relations, and it is this that Paul deals with in Romans

5:6-11 and in II Corinthians 5:18-21. For the Greeks reconciliation was

all-encompassing. The whole world of the convert is indeed changed as a result

of the deeply personal nature of the harmony that has been restored between a

sinful man or woman and his or her God. Those who were once outright ‘enemies’

of God and had every right to fear the consequences of the wrath of God are now

at peace and are saved by the initiative that God took through Jesus Christ

(Rom. 5:6-11).” (Gilliand

1983:100)

Another form of the vertical relationship found in Romans is the

“lordship” of the

risen Jesus over Paul since his conversion

(Act 9:4), the new Christian (Rom 10:9) and to be “affirmed over all people,

both the dead and the living (Rom 14:9),” “extends over both the lives of

people and the world in which they live” (Rom 10:9) (Gillian 1983:26, 51).

To Paul, the lordship of Jesus over “the world” is a relational

understanding. As

G.E. Ladd in A Theology

of New Testament. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. 1974:397-399) explained, the word “cosmos” (“the world”) as used by Paul referred to the universe

(i.e. the totality of all exists” (Rom1:20), the inhabited earth and the

dwelling place of man (1:8; 4:13), mankind (i.e. the totality of human society)

and angels (3:6, 19; 11:5). He

explicitly stated that “It is not merely the world of men but the worldly

system and the complex of relationships that have been created by men.”

Relational reading of

Romans: “indebtedness” (Rom 1:12; 8:12; 13:8; 15:27)

The

term “opheilete,” is used four times

in Romans with multiple meanings that can be described in terms of vertical and

horizontal relations spiritually, socially and missiologically.

Š

“Debt” in mission outreach - Rom 1:14

Paul

freely received “grace” from God (“received grace and apostleship” Rom 1:5). He wishes henceforth is to pay back his vertical

“debt” by sharing the gospel horizontally with Greeks and Gentiles, wise and

unwise (“I am debtor both to the Greeks, and to the Barbarians; both to the

wise, and to the unwise – Rom 1:14).

Paul

took many concrete steps to pay the “gospel debt” to those in Rome: praying for them (Rom 1: 8-10),

planning to pay them a visit (Rom 15:22-24), sharing with them spiritual

blessings (Rom 1:11), etc. Paul’s strong passion for the lost, his sacrificial

service, suffering for the sake of the gospel…are characteristics of a “debtor”

striving his best to pay back what he owed vertically to God’s grace and

horizontally to serve others.

Š

Not “debtors” to the flesh spiritually – Rom

8:12

A

gospel-transformed individual is not obliged to the flesh (“Therefore,

brethren, we are debtors, not to the flesh, to live after the flesh.” –

Rom 8:12). His experience is described in Rom 8:10, “And if Christ be in you,

the body is dead because of sin; but the Spirit is life because of

righteousness.” Vertically “the

Spirit of him that raised up Jesus from the dead dwell in you…quicken your

mortal bodies by his Spirit” (Rom 8:11). A gospel-transformed individual is a

“son of God” …led by the Spirit of

God” (Rom 8:14) and ought not be ruled by the “fresh” as if he is a “debtor” to

the fresh (Rom 8:12).

Š

“Debt” as the practical way to love - Rom 13:8

Horizontal relationships within the community of gospel-transformed

individuals are is to be characterized by “love” (“Owe no man any thing, but to love one another” - Rom 13:8). “Liberty” misused will result in “hurting your brother…no

longer acting in love” (Rom 14:15). “Liberty” can divide the weak from the

strong (Rom 14) but “love” (Rom 13:8) will bind gospel-transformed individuals

together. “Love” is to be practiced with an attitude of a “debtor” who after

receiving the “love” vertically from God is then obliged to “love” the brethren

horizontally as a way to pay back. “How Paul’s injunctions to love stand out!

They cover all attitudes, judge all motives, and guard every action. The

individual Christian is to learn love because he has been changed by love. Love

is characteristic of the Spirit and Spirit is the source of love (Rom 15:30;

Gal. 5:22).” (Gilliand 1983:130)

Š

“Debt” from spiritual blessings - Rom 15:27

Horizontal relationships of those who are

recipients of spiritual blessings are is marked as “debt” - “It has pleased them verily; and their debtors they

are” (Rom 15:27). Both the Jerusalem saints and believers in Rome are

recipients of God’s grace from God vertically. Yet horizontally believers in

Rome have been spiritually blessed by the suffering saints in Jerusalem and thus

are “debtors” to them spiritually. Now they are to share horizontally to meet

the material needs of those in Jerusalem.

Relational reading of

Romans: the truth of “gospel” and “grace”

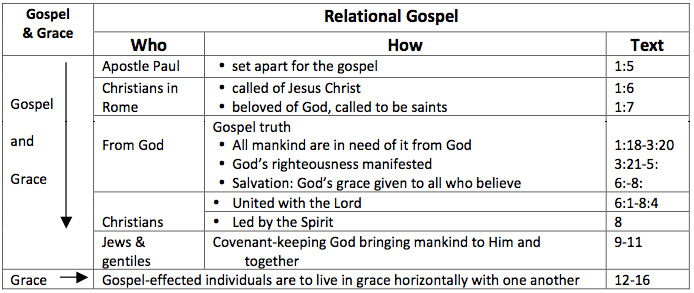

Paul

experienced firsthand the grace of God and the truth that the gospel is “the

power unto salvation” (Rom

1:16) thus to him the gospel is “truth about a living Christ…The vibrant

connection between himself (Paul) and the risen Christ amazed and encouraged…Paul

was to see this life-changing confrontation on the way to Damascus as an

expression of God’s loving grace.” (Gilliand 1983:23)

Paul’s

experience of being confronted by the risen Lord, which led to his conversion,

calling and commission,[13]

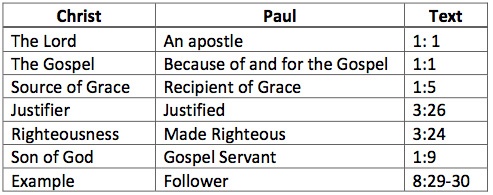

is closely linked to his theology. “Paul made personal relationships between

men and God a basic theme in his theology…It is impossible to imagine the

message of Paul without the idea of grace at the center.” (Gilliand

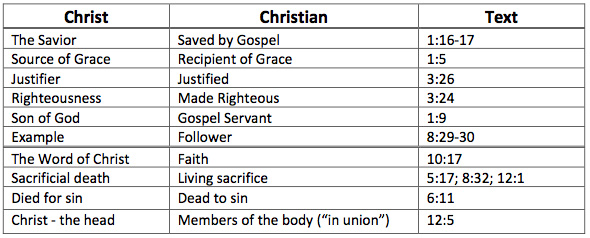

1983:25) The figure below lists

references in Romans and the relationship between Christ and Paul.

Figure 8

— Vertical relationship of the Gospel: Christ and Paul

Paul’s

self-identity is “I am an apostle to the Gentiles” (Rom 11:13) as distinct from

other apostles, if viewed in the light of Gal 1:15-16:

“God…chose

me even before I was born, and called me to serve him…he decided to reveal his

Son to me, so that I might preach the Good News about him to the Gentiles”

For

Paul, this “grace” (Rom 15:5) is a personal experience of transformation from being

a persecutor of the “risen Lord” to becoming an apostle to the gentiles.

Similarly, it is “grace” that the gentiles are collectively “grafted in” as

wild shoots (Rom 11:17), while the Jews have been “broken off” the tree of

Abraham. Thus the truth of “grace” introduced in Romans and the imagery Paul uses

(Paul personally and the gentiles collectively) are more suited for a

relational interpretation than doctrinal or rationalist interpretation.

“The ruling impulse” of Paul’s life was “to carry

Jesus’ Good News of universal grace far and wide” (Gilliand 1983:30) and his

sacrificial ministry for the gospel is his way of relationally reciprocating

the grace received.

In addition to the comments on “gospel” and “grace”

shown in Figure 5 above, “the obedience that comes from faith” of Rom 1:5 and

16:26 is to be reconsidered relationally. We can see that “the obedience of

faith” is exactly what Abraham demonstrated in response to God’s command and

promise.

“Faith” and “obedience” are the two words that are

most definitive of Abraham’s walk with God” (Wright 2006:247). The gospel of

grace from God vertically downward to man is to be responded vertically upward

by man to God by faith and obedience. Wright in the quotation below articulated

well this relational perspective:

“So

Paul sees Abraham not only (as all

Jews did) as the model for what should

have

been Israel’s covenantal response to

God but also as the model for all the

nations who would be blessed through him. We can summarize this double

message thus: The good news of Jesus is the means by which the nations will be blessed through Paul’s

missionary apostleship; the faith and obedience of the nations will be the

means by which they will enter into that blessing, or indeed in Abrahamic

terms, ‘bless themselves.’”

(Wright 2006:248) (italic – original)

Relational

reading of Romans: Paul’s priestly service

From

Rom 15:14-16, one can glimpse the “relational gospel” in

terms of Paul’s “priestly

service” (Strauss 2003:459) to the

Gentile nations (15:15-16). His vertical relationship with God resulted in him

being a servant of the gospel (Rom 1: 1-17). All these are closely tied with

his own conversion, calling and consecration, filled by the Spirit and

commissioned to be the bearer of the gospel to the region beyond (Act 9:10-17).

Paul

“pictured his ministry among the Gentiles” (horizontal dimension) as “an act of

worship, similar to that of an Old Testament priest bringing a burnt offering

to the altar” (Strauss 2003:460) (vertical dimension). Paul was accompanied by representatives

of Gentile churches in his journey to Jerusalem (Act 20:4-5) (horizontal

dimension) and may be considered by Paul as “a token and a seal of his own

greater and more far-reaching sacrifices to God” (Strauss 2003:460) (vertical

dimension).

“As

a priest, Paul had simply been the agent of God’s work” (vertically) in his

ministry of “bringing about the obedience of the Gentile nations” unto God

(vertical and horizontal dimensions combined).

Vertically

Paul’s apostolic calling is to be set apart for the gospel (Rom 1:1 & 1 Cor

1:17) and his subsequent service in the gospel (Rom 1:9) is horizontally

ministering to Jews and nations in his entire life. Paul’s priestly ministry of

evangelism is found in Rom 15:16, “the only place in the New Testament where

anyone speaks of their own ministry in priestly terms” (Wright 2006:525).

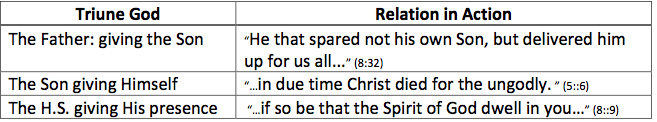

Relational

reading of Romans: the Trinity

It is impossible to review the many passages in

Romans dealing with the vertical relationship between the Trinity and

Christian; the figure below is only a sample from Rom 8.

Figure 9

- Vertical relationship: Triune God and Christians in Ro 8

Paul uses the term “philadelphia” only twice (i.e. earthly

and friendly love,

Rom 12:10; 1Thess 4:9); but he uses “agape” extensively elsewhere. The self-giving love of the Triune God moves

towards man vertically as the basis of self-giving love among gospel-effected

individuals moving horizontally.

Figure 10 — Pattern of the “Self-giving

Love” of the Triune Godhead

God accepts hostile

humankind into his holy fellowship and thus sets a pattern for people to deal

with one another. Miroslav Volf

(1996) conducted an extensive study on the social significance of “the divine self-sacrifice”

(i.e. God embraced rebellious mankind into

a divine fellowship and is the model of horizontal relationship within humanity,

1996:20) (Volf 1996)

Relational

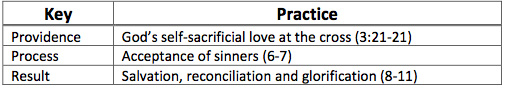

reading of Romans: the Cross and the Christian

The

“centrality of the cross” in Christian mission is well developed by Wright

(2006:312-323) and Romans

provides plenty of data to support it. “The cross” is the center of Paul’s

concern relationally in Romans as shown in the figure below:

Figure 11 —The Cross: God-man

vertical relationship

To

Paul, “the cross” is the death of Jesus and believers are to joint Jesus first in

his

death then resurrection.

Christians are spiritually dead because of disobedience and sin (Rom 6:8, 11;

Eph 2:1, 5) but are now alive to God. Thus for Paul “the cross” is a relational

reality, not merely a propositional understanding. The figure below shows the vertical relationship between

Christ and Christians.

Figure 12 - Vertical relationship: Christ and Christians

Since

the fall began with Adam (Rom 5:12-16), “humanity is a prisoner of war (Rom

7:23);”(Martin 1981:58-59) but in Christ (vertical relationship) there

is justification and life (Rom 5:17-21). In fact, the entire created order is

awaiting the full salvation (Rom 8:18-25). Therefore, there is more “in the

biblical theology of the cross than individual salvation, and there is more to

biblical mission than evangelism” (Wright 2006:314). Deriving from Rom 8:18-25,

Wright proposed that the theology of the cross is cosmic, holistic and social

in scope (Wright 2006:312-316).

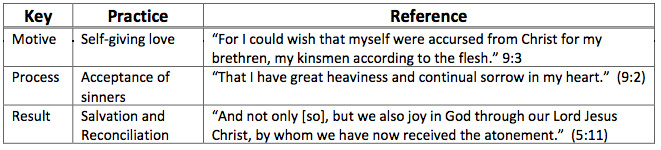

Figure 13 —“The Cross” -

Horizontal relationship between Paul & his kinsmen

In

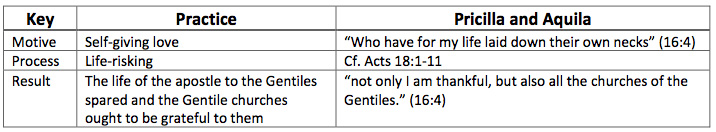

the concluding chapter of Romans, we find a case study for “the cross” in the

life- story of Aquila and Priscilla. They were political refugees from Rome and

hosted missionary Paul, even saving his life in Corinth. They were transient church workers and coached

Apollos in Ephesus. Later they

founded a house church in their home in Rome (Act 18; Rom 16:3-5). Paul’s commendation on their practice of

“the cross” is listed below.

Figure 14 — Horizontal

relationship of “the cross”— Pricilla and Aquila

Relational

reading of Romans: the gospel-effected community

The gospel is not merely a matter of vertical

“personal guilt and individual forgiveness” (Wright 2006:314). It has also a horizontal

or social dimension that should not be overlooked. This social or horizontal dimension is vividly described below:

“Sin

spreads horizontally within society and sin propagates itself vertically

between generations. It thus generates contexts and connections that are laden

with collective sin. Sin becomes endemic, structural and embedded in history.”

(Wright 2006:431)

Paul’s teaching about the

church in Rom 12:4-5 is best described in the vertical relationship to the

Head (“in union with Christ”) and

horizontally to one another as “members of the body” (12:5).

Figure 15

- Horizontal

relationship of gospel-effected individual

The

aggregate of gospel-transformed individuals are to live out the unmerited

“grace”

collectively in community, demonstrating the power of the gospel horizontally

in real life practice. [14]

The various

spiritual “gifts” (charistmata, Rom

12) are to be understood as unmerited endowment vertically from God and to be practiced

horizontally in service (diakonia) within

the context of the church.

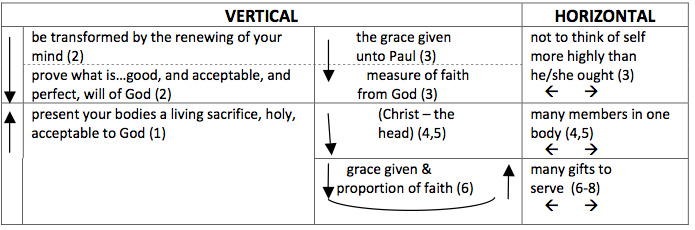

In Romans 12:1-8,

Figure 16 below shows the vertical and horizontal relationships of the

transformed individuals living collectively in community. They work out “grace” received in

“relational reality” (see earlier publications on “relational realism,” Wan

2006b. Wan 2007)

Figure 16 - Gospel-transformed

Individuals in Community: Rom 12: 1-8

4. CONCLUSION

In this study of the Epistle to

Romans, the author has employed a

missio-relational reading, complementary to other approaches, to gain

missiological understanding and demonstrate the viability of a relational

approach. A missiological reading of Romans was carried out

by identifying the double

motifs: “the gospel” and “missions” and Paul’s self-identity as “a missionary

to the gentiles.” A relational approach was demonstrated to be helpful in

studying the themes of “relational gospel,” “indebtedness,” Paul’s “priestly service,” and gospel-effected relationships

vertically and horizontally.

The missional aspects of Romans have been

highlighted for readers in the post-Christian west and relational insights are

introduced for the post-modernists who are starving for personal and communal

relationships.

LIST OF REFERENCE

Bowers, W. Paul. “Fulfilling the Gospel: The Scope of the

Pauline Mission,” Journal of the

Evangelical Theological Society (1987), 30:186.

Cranfield, C.E.B. The Epistle to the Romans (Edinburg: Clark, 1979), 1:441.

Gilliand, Dean S. Pauline Theology & Mission Practice. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1983.

Hedlund, Roger E. God and the Nations: A Biblical

Theology of Mission in the Asian

Context. 2002.

Martin, Paul P. Reconciliation: A Study of Paul’s Theology. Atlanta: John Knox, 1981.

Miroslav Volf, Exclusion & Embrace – A

Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness

and Reconciliation. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1996.

Tomson, Peter J., Paul and the Jewish Law: Halakha in the

Letters of the Apostle to the

Gentiles. The Netherlands, 1990.

Wan, Enoch “Relational

Theology and Relational Missiology,” Occasional Bulletin,

Evangelical

Missiological Society. (Winter 2007), 21:1, p.1-7.

Wan, Enoch with

Mark Hedinger. “Understanding

‘relationality’ from a Trinitarian

Perspective,” Global Missiology, Trinitarian Studies, (January

2006a).

Wan, Enoch. “Missionary strategy in the Epistle to the

Romans,” To the End of the Earth,

Hong Kong Association of Christian Missions Ltd. (July-Sept., 2005):1-2. (in Chinese)

Wan, Enoch. “The

Paradigm of ‘relational realism’,” Occasional Bulletin, Evangelical

Missiological Society. (Spring 2006b), 19:2, p.1-4.