We Compromise the Gospel When We Settle For Truth: How “Right” Interpretations Lead to “Wrong” Contextualization

Jackson Wu (PhD, Applied Theology)

Wu teaches theology and missiology to Chinese church leaders in Asia.

He maintains a blog at jacksonwu.wordpress.com

Published in www.GlobalMissiology.org Jan 2013

“Why did you marry your wife?” The man confidently answered the question, “That’s easy––because she’s a woman.” It is hard to dispute the point that this man’s reply is correct. At some level, even if only a technicality, his wife’s gender is a reason why he married his wife. Though the conversation is fictional, it aptly illustrates two points. First, the question “why” can have multiple answers. Recently, I heard a small group leader ask some other Christians, “Why did you become a Christian?” One woman answered, “Because my grandmother believed in Jesus and shared with me.” However, this was not the group leader’s meaning. He was not inquiring about the circumstances on their conversion; he was asking about their heart and motives. Second, one sees that an answer may be completely true, yet it may thoroughly miss the point at hand. Among the various true words that could be said, not all are relevant to a given context. Many people have had a similar experience when studying the Bible. Someone asks about the “meaning” of a text, at which time some people immediately talk about the application of a Scripture passage, skipping over the intended message of the author in its original context.

Much damage is done to the gospel and thus to missions when we settle for what is merely true. On the one hand, countless church divisions arise from false dichotomies that may amount to barely more than questions of emphasis. On the other hand, Christians may preach a “true” gospel yet be written off as irrelevant and foreign. To make things worse, missionaries may entrench themselves even more in their theological positions, claiming that the gospel is “foolishness” to their hearers, who are simply “blind” to the truth. We must consider the possibility that missionaries (as well as any other Christian) may in fact compromise the gospel even while affirming “right” interpretations. As a result, contextualization becomes excessively complicated and our theologies contorted.

One does not have to surrender his or her conviction of absolute truth to recognize the relative nature of biblical truth statements. For instance, many would be inclined to fire a pastor who emphasizes that “a person is justified by works and not by faith alone,” despite the fact that this is a direct quotation of Jas 2:24 (cf. Rom 2:6–7, which echoes Job 34:11; Ps 62:12; Prov 24:12; Jer 17:10 and even Jesus in Matt 16:17). Conversely, few would quibble with the person who similarly exhorted, “one is justified by faith apart from works of the law” (Rom 3:28). The statements by James and Paul are both true––from a certain perspective. Similarly, Chinese evangelists inquire with perplexity how it is that “God cannot be tempted with evil” (Jas 1:13) if Jesus is divine yet was tempted by Satan in the desert. Obviously, having an “either-or” perspective is not always helpful when interpreting the Bible. Often, one needs to seek a “both-and” solution in order to preserve the whole body of truth. If this point is not heeded, then a person can defends a “right” interpretation but wrongly severe it from the original text and thus undermine its significance for a particular context. At worse, “right” statements can so distort the truth they undermine the gospel entirely. For example, Paul’s Jewish would have been quite right to say that Israel had been chosen as God’s people to be blessed; however, this misses the bigger point of the Abrahamic covenant. Israel was blessed in order to be a blessing to the nations![1]

“It’s Not Wrong” and Other Ways We Miss the Point

Given that interpretation should determine application, then it is mere issue of nuance how one decides on a range of biblical and theological controversies. The way we read a certain phrase or the weight given to one motif over another sets the trajectory for the theological conclusions and missiological applications that follow. Potential problems are compounded when missionaries lack either theological training or the humility to see the weakness in their views. When debates are settled by “commentary wars” (in which people assert the comments in their study Bibles), then a stalemate is reached when someone finally exclaims about his or her own view, “It’s not wrong!”

In what follows, we survey a number of highly controversial topics where we have to examine whether or not people are “right” in what they affirm but “wrong” in what they deny, in which case contextualization is stunted by partial readings or by confusing the main point of a text with its implications. Given the volumes that have been written on each of the topic to be mentioned, this article cannot attempt to elaborate upon nuances and defend the competing perspectives. Furthermore, it would be shocking if most readers did not disagree with or at least have great reservations about some of the proposals I suggest below. Even if one disagrees with what is said, humility requires that interpreters at least consider the implications of such "both-and" interpretations. What if they are true and we have confused the primary point and its implications? In that case, one is not fighting against some heterodox or dangerous interpretation. Rather, one would be pitting Scripture against Scripture. The problem of conservative readings then may resemble that of so called liberals, since the meaning of the text may still be distorted via selective focus and emphasis. For disclosure’s sake, my background and close friends vouch for the fact that I am an evangelical with conservative leanings. Yet, whenever one takes seriously the possibility of “both-and” interpretations, many people will be ready to accuse him or her of being a closet liberal.

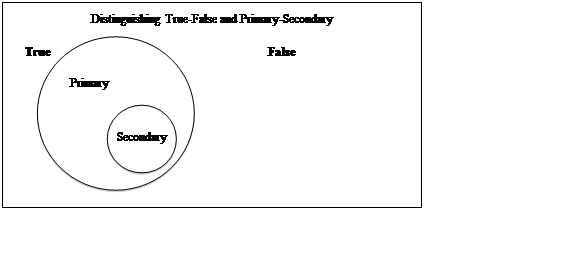

Emphasis is part of the original meaning of the author. For those who hold the Bible to be authoritative for Christian life and ministry, it is not enough to settle for mere truth. No doubt many fear that relinquishing a traditional interpretation is a step down the slippery slope of compromise. Of course, any Protestant can easily recognize an equal danger at this point––holding too tightly to tradition at the cost of Scripture. Admitting the possibility that we may not be fighting about what is true and false but instead what is primary and secondary can allay fear.

C. S. Lewis puts it succinctly, “Put first things first and we get second things thrown in; put second things first and we lose both the first and second things.”[2] His principle is not only relevant and encouraging but also sobering. Reflect again on the opening conversation about a wife being a woman. Being a wife implies being a woman; being a woman does not necessary mean being a wife. Though the logic is basic and obvious in this instance, one could miss such implications when talking about complex theological and missiological ideas. If we do in fact emphasize true but secondary points in Scripture, then what many things might we be overlooking which God has revealed and that may greatly impact missionary practice around the world? It is critical to not to confuse the questions of truth and matters of emphasis.

“It’s Completely True and Wonderful, But . . . ”

What are some biblical truths commonly taught within the church but miss the main idea of the text? Let’s start with some ideas that most people could agree with. The David-and-Goliath story is typically presented as teaching that God takes care of the little guy. Though this is a true point to draw from the passage, it should not be missed that God is using David so “that all the earth may know that there is a God in Israel” (1 Sam 17:46). God is center, not the individual. Pastors often suggest that being made in the image of God means we are rational, moral beings. True enough, but this is almost trivially true in that people are rational and moral since being made in the image of God primarily points to how we are to honor God via our vocation to be fruitful and exercise authority over the earth as God’s under kings (Gen 1:26–28; cf. 1 Cor 11:7’s emphasis on honor). One can survey a litany of gospel tracts that emphasize eternal life; that is, the length of time is given prominence. Yet, Jesus reorients our western fixation with time when he says, “And this is eternal life, that they may know you the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent” (John 17:3).

Why did Jesus die? John Piper has rightly puts first things first when he highlights from Rom 3 that Christ died for God, in order to show God’s righteousness.[3] If the church merely assumes the importance of God’s glory such that it has no practical effect upon one’s regular reading of Scripture, it will not be long before it be forgotten altogether. In addition, N. T. Wright observes Paul’s answer to the question as to why Jesus became a curse for us. It is not simply because Jesus loves us (though true). More precisely, it is “so that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles” (Gal 3:14).[4]

More controversial are questions about the gospel. In these debates, one side tends to accuse the other of being “reductionistic” and creating false separations. For instance, Scot McKnight’s The King Jesus Gospel (Zondervan, 2011) drew much concern from those who feared he was dichotomizing “salvation” and “story,” or salvation from Christ’s kingship (even though McKnight repeatedly says otherwise). However, what if McKnight is right (and, thus far, I have found no one who challenged his exegesis itself)? There is great consensus that historically and biblically speaking the concept “gospel” refers to an announcement on kingship or to a king’s victory.[5] If the gospel announces Christ’s Lordship over the world (cf. Rom 1:1–4; 1 Cor 15:4–8, 20–28), salvation is the wonderful implication of that gospel, then how would it radically reshape the way we evangelize to give priority to Christ’s identity and work then making clear the hope of (individual) salvation? The “then” implies “and.” There is no true separation. Because Jesus is Christ (i.e. King) and has defeated death, therefore people can be saved. Likewise, what happens when one preaches that salvation is “going to heaven?” This “true” comment may obscure ideas that are more central to the biblical hope, such as resurrected bodies and new creation. In addition, it is true that the gospel magnifies the death of Christ, but Paul says Jesus’ death means nothing if he did not resurrect (1 Cor 15:14–19). For Paul and the sermons in Acts, the resurrection is prioritized. Sadly, too many gospel tracts and confessions barely mention and even omit the resurrection.[6] Yes, Jesus died on a cross. While this is glorious and true, there is an even bigger point to be made––he rose!

One of the most important debates among theologians over the past few decades concerns the “New Perspective on Paul,” which examines the meaning of justification. Is justification about ecclesiology or soteriology? Although the “old” and “new” perspectives would admit that justification affects both, few show how Paul integrates both into his doctrine. In particular, some says that the “Law” refers to the Mosaic Law and is an ethnic badge signifying Jewish identity. Traditionalists affirm that “law” in Romans and Galatians refers to a general moral law and that Paul opposes legalism or works-righteousness, not ethnocentrism.

The gospel that missionaries preach will be greatly affected by how one answers the question as to whether the law is primarily an ethical or an ethnic category. For example, what is one to do with the typical Chinese or atheist who is in no way trying to gain God’s salvation via works-legalism but instead goes about his life seeking to gain face from family and peers? What are we to do about the fact that “law” is not a major cultural motif in Chinese thinking, but rather honor-shame is the foremost concern? Is one forced to first change his worldview to a more legal orientation so that he can understand the westernized gospel presentation? Once he becomes sufficiently western, then he can become a Christian? Consider the Chinese word for “sin,” translated zui, which means “crime.” By choosing a legal motif, missionaries often confuse Chinese people, who are immediately confused to hear that they are “criminals.” Not even Paul absolutely prioritized the legal motif when describing sin. Romans 2:23–24 says, “You who boast in the law dishonor God by breaking the law. For, as it is written, ‘The name of God is blasphemed among the Gentiles because of you.’” In Greek, the verb of v. 23 is “to dishonor.” “Breaking the law” is simply the means by which these Jews dishonored God. Breaking the law is sin but sin most basically is the dishonoring of God (cf. Rom 3:23).

One can rightly affirm the points that justification has a legal dimension and that “law” is a moral, God-oriented category; nevertheless, consider the implications if Paul actually reverses what people traditionally think to be first and second. What if Paul is fighting against an ethnocentrism that supposes being Jewish is the most basic precondition to being justified as one of God’s people? What if the Jews regarded works of the law as a means of “ascribed” honor, not simply “achieved” honor?[7] From an honor perspective, legalism in not the only reason one might boast. The Mosaic Law is ethnic inasmuch as it distinguished Jews from Gentiles; it is ethical in that the Law issues forth God’s own commands to his people. Yet, Paul is not rebutting the moralistic Gentile who thinks circumcising himself will save him apart from his becoming a Jew. The Mosaic Law’s ethical force was felt within an ethnic context. However, if we emphasize a right doctrine––that God’s Law is authoritative and shows people to be sinners––we can easily miss how Paul is overtly confronting ethnocentrism as a soteriological problem, not merely a sociological issue. By putting first things first, we see how Paul addressed the same sort of problem evident around the world in our day––ethnic and group pride––without losing the legitimate application that we are not saved by slavish conformity to God’s decrees.

Consider whether it is right to say the following: “God is love but he is also righteous; therefore, he must punish sin.” No doubt, someone can affirm this as true. On the other hand, this is not the typical way that the Bible talks about God’s righteousness. Certainly, punishing sin is right and various texts link God’s righteousness and punishment; yet, these punishment verses typically come in a context in which God is saving his people.[8] To look at it from another angle, assess which of the following sentences is correct: “Although God is righteousness (and must punish sin), yet he saves sinners,” or “Because God is righteous, therefore he saves sinners.” The first sentence makes God’s righteousness an obstacle to salvation; the latter treats God’s righteousness as the reason for salvation. The first sentence is a rather standard way of speaking within evangelical circles.[9] Although true enough, it obscures the Bible’s main point when using this sort of language. Among many passages that could be cited, Ps 143:1, 11 illustrate the Bible’s own way of talking about God’s righteousness. The psalmist prays, “Hear my prayer, O LORD; give ear to my pleas for mercy! In your faithfulness answer me, in your righteousness! . . . For your name’s sake, O LORD, preserve my life! In your righteousness bring my soul out of trouble!” Likewise, Ps 51:14 says, “Deliver me from bloodguiltiness, O God, O God of my salvation, and my tongue will sing aloud of your righteousness.” The verse makes no sense if David refers to God’s righteousness as God’s punishing David’s sin. We should not set God’s “saving” righteousness against his “penal” righteousness. After all, God saves his people by judging their enemies. Wrath is the means by which God remains faithful to his promises. It is true that God’s righteousness most broadly points to God’s doing right. However, we do not want to functionally edit out the Bible’s primary connotation of God’s righteousness because theologians have traditional highlighted what is merely a true implication.

Other topics suffer a similar fate whereby the main idea is sacrificed because some other idea “is not wrong.” Yes, the resurrection has apologetic value, but the Bible stresses its theological importance. Yes, we are all sinners because of Adam, but this statement may not account for the function Adam serves within Paul’s theology; within Acts, no one begins with Adam as a proof text for the fact we are all sinners. Yes, Jesus is both divine and human, yet what is sacrificed when missionaries miss the primary meaning of the terms “Son of God” (i.e. Israel’s King; cf. 2 Sam 7:14; John 1:49; et al) and “Son of Man” (cf. Dan 7:13)? How would it affect missiological labor to use titles as Nathanael used them, “Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” (John 1:49)? Yes, it is true Gen 1 teaches that God created the world, but this ought not cause us to focus on secondary concerns of the text itself. Rather, like the psalmist who interprets Gen 1, so also we should give our foremost attention to the fact that this one true Creator God is glorious, sovereign, and worthy of praise (cf. Ps 104). Theism and monotheism are true enough (even the demons believe this and shudder, Jas 2:19); yet, overemphasizing these and other “right” interpretations can lead to innumerable “wrong” approaches to contextualize our message and strategy.

Are missionaries teaching “the right doctrine from the wrong texts?”[10] If so, we may overlook many ideas that God has revealed and the original authors intended to convey. The point of this essay is not to offer a scholarly defense for each of the various points of debate. Instead, it argues that we risk compromising the biblical message when we settle for truth––what is merely true but not the main point of a text. In the process, one sees the fundamental importance of hermeneutics (not just theology) in missions and the global church. Missionarytraining must emphasize biblical theology, not simply systematic theology. In so doing, the Bible will not merely answer our questions; furthermore, it will pose many unexpected questions of its own, which should shape one’s theology and missiology.

Why All Theologians Should Become Missionaries: An Evangelical Model for Interpreting Ancient Scripture with Contemporary Culture

We are predisposed to see as the emphasis of a text the kind of things that are emphasized in our own cultural backgrounds. This is because we naturally try to organize biblical teaching into the mental categories native to our worldview. If one is to make sense of the world, it is only natural to use familiar patterns of thinking. One’s assumptions are countless and unconscious.[11]

In order to interpret and apply Scripture, it is critical that we balance our particular perspective by becoming aware of other ways of seeing the world. As one theologian rightly states, “[A] cross-cultural reading is more objective than a monocultural reading of the biblical text.”[12] Inevitably, people from some cultures will more easily grasp aspects of biblical teaching than those from other cultures (and time periods). However, such varied ways of judging and prioritizing human experience would also seem to render contextualization nearly impossible. Even when people share common cultural backgrounds, biblical interpretation is already difficult enough, since one tries to understand a text from the view of the original writer within his own historical setting. Various interpretations have differing points of emphasis due to each person reading Scripture a contrasting cultural milieu. Trying to reconcile these competing ideas only complicates the interpretive process. Interpreters will be tempted to accuse one other of eisegesis, whereby people force a meaning unto the text that is actually foreign to the author’s intent. Likewise, readers will be quite unaware of their own eisegesis, since they unwittingly presume the biblical author categorized the world in the same general ways that they do. Naturally, one should not assume that these differing interpretations contradict; they may simply have distinct points of emphasis.

At one level, general revelation and the basic structure of the world ensures that people can find common ground for communication and interpretation. Regardless of time or place, people understand concepts like family, authority, law, honor, morality, and relationships. Biblical authors use a myriad of such “human” categories (perhaps in the form of metaphors) to communicate significant truths. In that sense, people’s ability to understand special revelation is quite dependent on their experience and/or general revelation. For example, just the doctrine of salvation alone employs various concepts, including slavery, glory, fatherhood, sonship, law, shame, righteousness, mercy, loyalty, and sacrifice. Since people are made to know God as revealed in Scripture, one naturally expects the Bible to speak in some manner that makes sense to people in every culture.[13]

On the other hand, any number of biblical motifs will seem obscure to countless people due simply to basic human limitations and differences. For example, daily life in 21st century America will not make it easy to grasp the significance of ancient near eastern kingship, the covenant concept, and collective identity (as opposed to the individualism endemic to western society). Some texts will typically cause more tension to grow within an Eastern reader than in a Western reader. For example, Gen 2:24 says, “Therefore, a man shall leave his father and mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall be one flesh.” Those who are more individualistic will hardly feel the weight of Jesus’ words, “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple” (Luke 14:26). Every cultural perspective has inherent blind spots, which then hinder biblical interpretation and thus contextualization. What can be done to account for the plethora of global perspectives while at the same time centering our interpretation (and eventual application) on the author’s original meaning?

The following model suggests that missionaries and theologians alike can actually use contemporary cultures as a means of interpreting the ancient biblical text.[14] This could be referred to as “reaching back by reaching out.” In one sense, all people living today face the same challenge of crossing thousands of years to regain the perspective of the biblical writers. Ultimately, this chasm cannot be overcome; however, what is variable is the perspective from which we examine the historical evidence that sheds light on Scripture’s meaning. As a person learns about or even internalizes ways of thinking typical in other parts of the world, he or she gains two things––a measure of objectivity and a broader understanding of what it means to be human. As a result, various assumptions are exposed and questioned. More positively, fresh insights are possible due to the new awareness one gains. One must be careful to admit that no contemporary culture is identical to any of the many ancient cultures depicted in Scripture.

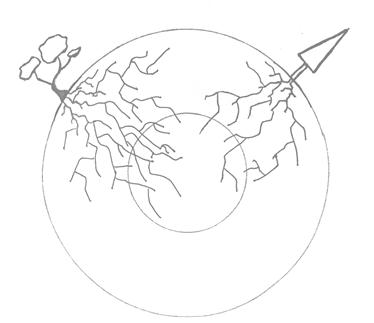

However, there will certainly be differing degrees of overlap or congruence. In some respect, East Asian cultures today may better resemble the Ancient Near East than would those of Chicago or a Los Angeles suburb. In other ways, one may find echoes of Scripture more clearly in traditional African thinking. Such themes may be less pronounced in London or Paris. Inasmuch as similarities exist between modern and ancient worlds but differ in degree between contemporary settings, interpreters from various locations will have advantages and disadvantages when reading the Bible. Of course, the advantages are not absolute. They are relative to the topic and theme. Human cultures complement one another.

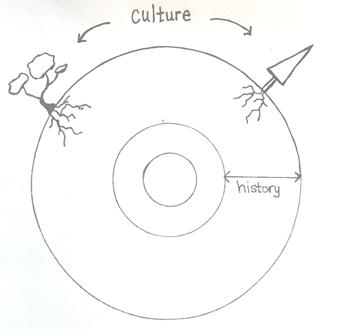

The graph illustrates the process of interpretation whereby one can better grasp the biblical context by reaching across the world’s contemporary cultures. The world’s cultural history can be mapped as a globe. We must think in two directions. The earth’s surface represents modern-day societies. Everyday, planes move people laterally on the global map. At the earth’s core are the very first human communities. The movement from the center through the earth’s layers to the crust delineates the evolution and interweaving of human cultures. While there are no neatly defined lines to demarcate one culture from another along successive periods, one can still speak in broad categories, trends, and characteristics. There is both continuity and discontinuity. More recent civilizations (nearer to the earth’s crust in the diagram) are birthed out of the cultures that came before them. Otherwise said, contemporary cultures are amalgamations, having histories fused in incomprehensible ways. Vast differences aside, these younger societies have in common many aspects from the world’s ancient civilizations. Therefore, some may describe a place like China as an “honor” culture rather than a law-guilt based culture, yet law related concepts (e.g. judges, order, politics, etc.) are not foreign ideas. In much respect, the earliest human cultures typify what is most basic to being human. What follows from the first peoples of the world are simply creative adaptations and expressions of essential humanness. To use the notion of imago Dei, every culture distinctly manifests the same image of God, according to which humans are created.

Cultures can be represented as trees, because they are living, varied, and rooted in the ground from some time past. Naturally, some trees have shallow roots; others go much deeper. They all spring from the earth below from which they get nutrients. In the model presented here, the roots represent the ways in which contemporary cultures emerge from previous civilizations. The process is natural but complex, mysterious but reasonably comprehended at the risk of abstraction. People can understand a culture’s influences if they dig closer to the surface, such as researching recent historical events and figures. It is less difficult to understand the influence of the civil rights movement on 21st century America than it is to see how 6th century Egyptian society precisely weaved its way through medieval Europe to eventually shape present day American culture. Although it is difficult to make conclusive judgments about the ancient world, scholars can unearth a range of useful insights with collaboration and effort. Of course, historical and cultural research takes place around the world. As people trace their roots back in time, they find increased interaction among the mother civilizations to the modern world. For example, the Silk Road famously spanned Asia. As a result, countless cultural exchanges no doubt spawned new communities and ways of thinking that continue to influence us today. Simply put, present-day cultures at one level or another share common ancient histories. Inasmuch as the world’s people share common origins or background, various themes will reappear again and again in cultures both across time and geography. For example, ancient cultures are often depicted as collectivistic and honor-shame oriented. Such descriptions do not deny ancient cultures had individualistic or law-oriented features as well. Not surprisingly, wherever one looks in history or around the world, humans still continue to be concerned with things like group-identity, reputation, and related matters.

One begins to see how crossing contemporary cultures equips people to better interpret Scripture yet without succumbing to naivety regarding the revelatory power of culture. This model posits a view of world and revelation similar to Albert Wolters, who writes,

Because [Christians] believe that creational structure underlies all of reality, they seek and find evidence of lawful constancy in the flux of experience, and of invariant principles amidst a variety of historical events and institutions. . . . In every situation, they explicitly look for and recognize the presence of creational structure, distinguishing this sharply from the human abuse to which it is subject.[15]

Of course there are no guarantees that a person with a multicultural perspective will actually be a better theologian; after all, “the everyday components of our lives––our family, our sexuality, our thinking, our emotions, our work––are the structural things that are involved and at stake in the pull of sin and grace.”[16] The point is that all things being equal, a multicultural approach is advantageous for seeing things in the text that are actually there but could otherwise be missed with a monocultural view. When it comes to interpreting the Bible, the distinction between missiology and theology should be less clear. Missionaries and missiologists should be among the world’s finest theologians. Likewise, theologians would be helped not only by reading books about the Ancient Near East but also by visiting or living in the modern-day middle and far east.

In the model presented here, moving horizontally across cultures gives a person varied degrees of access to past civilizations and worldviews. For example, an American who travels to China will quickly realize the importance of collective identity, “face,” and hierarchy to the Chinese people. Such priorities echo those of ancient biblical cultures. As one better understands these values and the internal logic of this kind of worldview, Christians will “have eyes to see” key themes and motifs within passages that previously seemed so familiar. Suddenly, their new awareness and appreciation for the way people think around the world becomes key to digging deeper into the biblical author’s original meaning.

There are certainly objections that could be raised and which are needed warnings. First, we should not equate any modern culture with an ancient biblical culture. Chinese culture is not that of Abraham, David, Jesus or Paul. The point being made is that these cultures have overlapping themes of emphasis or “creation structures,” to use Wolters’ phrase. Even if particular details differ between them, readers at least are made aware that these values and categories of thought are to be taken into consideration. A second concern is eisegesis, whereby the reader’s own assumptions (not shared by the original author) force an interpretation unto the text. Frankly stated, this is a danger for every interpreter and even more so for the person who only uses a monocultural perspective. In fact, one could counter that a multicultural perspective actually helps to minimize eisegesis because he or she is more aware of a broader range of issues that have concerned humans throughout history. Finally, a third concern is that of relativism. Does this model collapse into relativistic interpretations and so water down the absolute authority of God’s revelation? No, not at all. All interpretations center on the meaning of biblical text as intended by the writers in their contexts. All biblical interpretations are bound by this common locus. Reconsider the proverbial analogy of the blind men who all touch different parts of the elephant. Lesslie Newbigin rightly points out that the word picture is self-defeating because the narrator, rather than proving relativism, actually presumes an absolute perspective and a common object of study.[17] There are only so many parts of the elephant that can be touched. If the blind men talked with each other, they would in fact get a very solid understanding of what they were all touching. Though each person has his or her own blind spots, collaboration opens one’s eyes to see far more than would ever be possible alone.

Briefly, I will highlight a few implications. First, this model makes a good case for long-term missionaries. Short-term work does not afford the kind of reflection and internalization needed to grasp the way locals see the world. In fact, brief exposures to another culture can easily reinforce pride in one’s own culture, fueling prejudice and narrow-mindedness. An overemphasis on short-term missions must not become a detriment of long term funding, training, and placement. It is long-term workers, who have deeper relationships with locals, that will have the greater opportunity to develop contextualized theologies. Second, it is imperative that we encourage and develop global theologies, not being content with only Western (i.e. traditional) theological formulations. Doing this will require tremendous humility, cooperation, intentional training, and a shift in priorities. Third, any particular cultural perspective by itself is insufficient to holistically interpret Scripture. Fourth, it follows that we should purposefully use other cultural perspectives to interpret Scripture. Fifth, the model illustrates the importance of the doctrine of humanity and of general revelation. Sixth, second culture people (including second generation children) could potentially be key people to assist the contextualization process. Seventh, we humans are more alike than we think. This observation should humble us and make us more open to the insights of others around the world.

Why Are Christians Talking Past Each Other?: An Examination of Seven Differences in Cultural Worldviews and How They Shape Theology

We can talk endlessly about points of theology but we eventually have to address underlying, deeper level issues. If one does not take seriously the significance of other cultural perspectives, he or she can very easily begin to either patronize or resent those from other cultures. Again, taking seriously other’s views does not at all mean wholesale agreement. In fact, serious engagement will often result in much disagreement precisely because the differences become clearer. At times, initial protests against another worldview (or its resulting theology) will subside as one gains better understanding. The purpose of comparing views is not to choose one over another. To begin with that as the goal is simply to beg the question, to assume that one faces an either-or dilemma. Instead, we hope to discern whatever truth does exist within the various choices. Habitually forging dichotomies can be fatal to theologizing. After all, two seemingly contradictory alternatives may in fact be true, but from different vantage points.

Take for example the frequent contrast made between law-guilt and honor-shame. Writers commonly treat law-guilt as an objective category (thus most important for theology) but then treat honor-shame as a mere social or psychological category (rather than a major theological concern). Accordingly, theologians often give their most rigorous attention to issues of law-guilt. Honor-shame can easily be overlooked as a mere cultural metaphor useful for contextualization but not essential for theology. It is easy to miss the obvious point that law is just as much a social metaphor as honor or shame.

This section that follows compares seven areas that are typically used to contrast a “Western” and an “Eastern” worldview. One should not suppose that these seven differences are exhaustive. In addition, the following are simply general characterizations. Analyzing cultures requires some degree of abstraction. There are also exceptions and varying degrees of conformity between individuals and their culture. Nevertheless, the descriptions represent broad trends as identified by scholars in various fields. Scores of books and articles have discussed issues related to each of the highlighted categories. The purpose of this section is simply to illustrate how seeming dichotomous ways of thinking each find support in Scripture. Since this is simply an introductory discussion, I will not attempt to present an extensive defense of each view. However, it is hoped that this section will spur fruitful reflection among theologians and missiologists. In particular, what aspects of our theologies and contextualizations need refinement and expansion? Although this article focuses on contrasts between East and West, other comparisons could just as well be used to one’s benefit.

Easterners and Westerners, stereotypically speaking, have two views of history respectively––cyclical and linear. Eastern cyclical thought is most pronounced in Buddhism, with its notions of samsara or reincarnation. Western thinking is often linear and emphasizes logically sequence. Western theologians are quick to contrast a “Christian” view of history and Eastern views.[18] According to a linear construction of history, creation marks the beginning of a long but purposeful process that culminates at a definitive end, namely Christ’s return, God’s judgment, and the new creation. The universe is not random. Christians deny the futility of fatalistic views of history. It is difficult to find Christians who disagree in this general assessment of history. Is this the only way to conceive of history?

Is cyclical thinking contrary to Scripture? Biblical theology gives good reason to temper objections. At one level, the cyclical nature of the world is the fundamental assumption of Ecclesiastes.[19] In addition, scholars have long recognized that authors frequently use typology to convey their meaning. Paul for instance says that Adam was a “type” [tu,poj] of the one who was to come” (Rom 5:14). In 1 Cor 15:45, Christ is called “the last Adam.” Some also “view Adam to be a type of Noah in the Genesis narrative itself.”[20] The tabernacle, its gifts, and sacrifices “serve a copy and shadow [u`podei,gmati kai. skia/|] of the heavenly things” (Heb 8:5). The OT sees “Israel as a new Adam/humanity”[21] yet in another sense Israel simply repeats the fall of Adam. Exodus language is used in the prophets (pointing to the end of exile and the salvation of God people) and in the New Testament.[22] This typology is also evident in rabbinic literature.[23] Beale speaks of “segments of the OT where there are repeated narrations of Yahweh’s commissioning people to fill certain offices (e.g., judges, prophets, priests, kings, and other leaders), the repeated failure of the one commissioned, followed by judgment, and the cycle starts again in the following narrative.”[24] In the Davidic covenant (2 Sam 7; 1 Chron 7), there is hope that the cycle will end. David himself becomes a type-figure for Israel’s kingship and ultimately for Jesus himself. Furthermore, Wright summarizes what many other scholars have also observed in Matthew’s Gospel:

[T]he life of Jesus recapitulates key elements in the earlier story of Israel. For a moment, as Jesus stands on the mountain giving the famous sermon, he is Moses. For a moment, answering his critics about his actions on the Sabbath, he is David. For a moment, as he calls and names the twelve disciples, he is perhaps Jacob, bringing the twelve patriarchs into the world. For a moment, healing the sick and raising the dead, he is Elijah or Elisha. And so on.[25]

More could be said than this brief overview allows. From one perspective, the Bible presents history as cyclical. God accomplishes his purposes through a series of events in which later events echo past ones. In a sense, history continues to repeat itself. This is not a vicious cycle that amounts to fatalism. Rather than thinking in two dimensions (either as a line or a circle), one can think of a spiral or cone. There is progress with each cycle; nevertheless, the circular fashion in which God works is unmistakable. In light of these observations, perhaps one could say Jesus brings final salvation such that the new heaven and new earth finally breaks the cycle of birth, sin and death.

A second contrast could be made and concerns one’s view of humanity, naming whether a culture is generally individualistic or collectivistic. Traditional Western theology and gospel presentations have especially highlighted individual salvation.[26] By comparison, it is less obvious that theologians have allowed a collectivistic worldview to strongly influence their theologies; in some cases, there seems to even be strong resistance to collectivistic readings.[27] This neglect is difficult to justify. Throughout Scripture, great attention is given to the question, “Who are God’s people?” or “Who are Abraham’s offspring?” One immediately thinks of the Jew-Gentile controversies highlighted in Acts 15, Romans, Galatians, and Ephesians 2–3. Jesus had a similar dispute in John 8:31–58. The fundamental distinction in the OT narrative is Israel and the nations. The nations disperse from the Babel (Gen 11), are made disciples via the Great Commission (Matt 28:18–20), and gather to worship Jesus in Rev 5:9; 7:9. Individual identity is not determined merely by how one is different from others; it also consists in how one is similar to others. Identity is formed by one’s membership in a group, such as family, country, school, team, friend group, etc. Individuals exist within relationships. In Matt 25:31–46, Jesus taught that the way we treat his people is the way we treat him. Paul hears the same message from Jesus on the road to Damascus (cf. Acts 9:4–5). The Church is a body with many members (1 Cor 12:12–27; Col 1:18, 23). Fundamentally, is the Church then “one” entity or a “collection” of parts?

Some people may see oneness where those from other cultures see separation. It is impossible to be dogmatic and claim that the Bible must be oriented individualistically rather than collectivistically. Both views could be pressed to unhealthy extremes; however, both have a place in forming a robust biblical theology.

A third set of differences has briefly been addressed––law-guilt versus honor-shame. A few additional observations and comments are still needed. Are legal categories central and honor-shame peripheral? An Eastern worldview sheds light on a number of passages. In Romans for example, Paul gives unmistakable priority to honor-shame when he writes, “You who boast in the law dishonor God by breaking the law. For, as it is written, ‘The name of God is blasphemed among the Gentiles because of you’” (Rom 2:23–24) In Greek, the verb in v. 23 is “dishonor” (avtima,zeij); “breaking the law” is a noun set within a preposition (dia. th/j paraba,sewj tou/ no,mou). Verse 24 reinforces the interpretation. Law-breaking is simply a means of the essential problem––not giving God “face.” Unrighteousness in Rom 1 is not defined in terms of law-breaking but rather in overt honor-shame language (1:18–28). Sin is “falling short of the glory of God” (3:23). Those who are justified “will not be put to shame” (cf. 9:33; 10:10–11). The faith that justifies gives glory to God (4:20). Being justified, one “[boasts] in the hope of the glory of God . . . and hope does not put us to shame” (5:2–5).[28] Indeed, God does everything for the sake of his glory (cf. Rom 15:8–9).[29] Rather than setting law and honor in tension, those engaged in contextualization and theological study do better to find how they are interrelated. More has been said on this topic elsewhere.[30]

Fourthly, Westerners and Easterners tend to have different approaches to the question of knowledge and reality. Western education and scientific inquiry highlight the importance of analysis, abstract thinking, and logical coherence. Many Easterners, on the other hand, are less inclined to such speculation, whether philosophically or in religion. In Analects 2:2, Confucius teaches, “Until you are able to serve men, how can you serve spiritual beings? Until you know about life, how can you know about death?”[31] Chinese have a pragmatic approach to life. They first seek to know if an idea works for some practical end. Thus, religion is viewed as a means to getting blessing in this present life. Chinese philosophy stresses harmony. The European and American church has contributed greatly to a systematic understanding of Scripture. A typical seminary student spends two or three courses at least in studying systematic theology. However, those with more pragmatic proclivities serve the church by drawing our attention to parts of the cannon that may easy get overshadowed by the Pauline epistles. Proverbs for example is full of practical advice for living a righteousness life. Psalms and Ecclesiastes give sobering reflections that challenge Christian idealism. The more pragmatic theologian will help us see a better connection between Paul’s theology and the latter half of his letters, where he applies the former. When the global church interprets Scripture together, Christians are helped not merely to settle for right ideas but also to glorify Christ in right practice.

With respect to moral truth, Western apologists affirm absolutism and reject relativism, which is a common perspective among Eastern societies. Once again, Christians would not disagree that God himself is the absolute standard by which one measures truth, right, wrong, good and evil. Relativism generally asserts that truth and morality depend on circumstances and culture. One cannot claim dogmatically that what is right for you is right for me. It would seem that relativism has no place in biblical interpretation and must be resisted in contextualization. However, even here, it is important to patiently take the time to understand the values that underlie relativistic thinking. First, by “relativism,” one need not imply utter and direct contradiction. For instance, anyone can easily recognize that deciding on what is right and wrong, practically speaking, depends on one’s situation and relationship. Sexual relations are right in marriage but wrong with someone else’s spouse. In the OT, God approves of Israel destroying her enemies yet Jesus’ command to love our enemies also means that it is wrong to take revenge (cf. Rom 12:19). In one sense “no one is righteous” (Rom 3:10), yet in Ps 14, from which Paul quotes, the psalmist then adds “God is with the generation of the righteous” (Ps 14:5). Meaning is relative to context and perspective. Hence, 1 Chon 21:1 says Satan incited David to take a census whereas 2 Sam 24:1 says is was the Lord who moved David to do it. Scripture commands us both to honor and hate our parents (Ex 20:12; Luke 14:26). We should always preach the gospel, except when we shouldn’t (cf. Matt 14:13, 23). We should always rejoice and yet “weep with those who weep” (Rom 12:15; cf. Phil 4:4). Famously, Jesus “relativized” the OT Sabbath laws. A fruit of the Spirit is self-control yet Paul says, “But if they cannot exercise self-control, they should marry. For it is better to marry than to burn with passion” (1 Cor 7:9). Discerning the relative value of absolute truths will help us better to discern sin from what is simply weakness. An Eastern perspective contributes a dose of humility to the Christian life. Critical realism can steer the interpretive process away from a naïve dogmatism that affirms merely correct answers but with little regard for context.

Western and Eastern habits of thinking can influence the interpretive process itself, not only the results of one’s theologizing. As Richard Nisbett points out, Westerners are prone to dichotomous, either-or thinking whereas Easterners tend towards harmonizing ideas, identifying both-and relationships.[32] Chinese seek a “middle way” (zhongyong) between the two extremes.

In research, it was found that Chinese judged a “more plausible proposition as less

believable if they saw it contradicted [the alternative] than if they didn’t” whereas Americans were likely to believe the “more plausible proposition more if they saw it contradicted [the alternative idea] than if it didn’t.” [33]

Neither tendency is necessarily desirable. Within Western Christian history, how many controversies and divisions derive from a lack of appreciation for both-and thinking? Countless disputes polarize two options, whether concerning the divine/human nature of Christ, God’s sovereignty and human responsibility, the place of works and faith, or the divine/human authorship of the Bible. On the surface of things, if there were ever a contradiction, it would appear to be when Paul says, “one is justified by faith apart from works of the law” (Rom 3:28) yet James says, “a person is justified by works and not by faith alone” (Jas 2:24). Both East and West could benefit from one another. Perhaps a number of tensions within Western theology would be eased as western Christians become proficient as both-and thinking. Likewise, as Easterners understand Western thinking, they may find themselves guilty of syncretism, thus compromising biblical truth.

Finally, it would not be surprising to find Eastern and Western Christians diverge in their appreciation for biblical genres. Chinese education emphasizes memorization. Students must spend considerable time not only memorizing classic works; also, simply learning the Chinese language requires extensive time and practice since it is a character based system. Lacking an alphabet, every single character must be learned through rote memory. Chinese have a high regard for tradition and history. By contrast, Western pedagogy stresses logical problem solving and debate. Creativity and novelty are valued. Not surprisingly, much time is spent in the West on systematizing theological points and developing new ministry methods. Without question, this effort has benefited the church. Western Christians have a high regard for Paul’s letter (as they should). Relatively speaking, there is less stress laid on narrative books and the OT wisdom literature. The Bible utilizes a number of genres. We must be careful not to create a cannon within a cannon, centered on our preferred genre. Theological provincialism is a natural result when churches do not seek to think outside the local and traditional box. Unfamiliarity breeds uniformity and conformity, undermines the unity of the global church, and compromises biblical theology.

Context is King All Over the World

This essay highlights a simple point that is easy to miss: One may have a “right” answer but still be wrong. From one perspective, the logic of our conclusions may be sound. However, when interpreting the Bible, we may ignore the main point of a text or be ignorant to the ways our own context influences our reading. Consequently, the church will be hindered in its application of Scripture. As missionaries cross cultures, they unknowingly have blind spots that affect their teaching and practice. Ironically, local Christians may inherit the missionaries’ cultural blind spots (when it comes to their faith) even though that area of weaknesses is not inherent to the local culture. For example, a Chinese Christian may understand the importance of group identification as a Chinese person yet be quite individualistic in his or her involvement with the church. We compromise the gospel when we settle for what is merely true because many “right” answers can lead to applications that are not appropriate to the text or the local context. These so-called “contextualizations” may lead to an unexpected sort of syncretism. This is a syncretism oriented to a denomination, theological tradition, or the missionary’s home culture.

Contextualization starts with interpretation, which centers on the Bible. This essay shows that the maxim, “Context is king” can be interpreted and applied in two ways. Biblical interpretation seeks to find the biblical author’s meaning within his original context. In addition, interpretation means that the interpreter’s own cultural context limits the kind of things he or she will tend to see and emphasize. Since the Bible is God’s revelation for all humanity, one would expect a global perspective to open one’s eyes to new insights that previously lay in a cultural blind spot. Fundamentally, we are humans, made in the image of God and not simply “Westerners” or “Easterners.” Accordingly, this essay suggests a model by which one uses present-day cultures to better understand ancient Scripture. Interpreters are urged to seek a broader understanding of the human context, both globally and historically; in so doing, they become acutely aware of themes that are in the Bible but have never figured prominently in their daily life. As a result, a multicultural perspective can help reconcile various tensions in Scripture and equip the church to develop faithful, contextual theologies.