Understanding and Responding to the Prosperity Gospel in Africa

Jim Harries[1]

Professor of Religion (Global University)

Missionary in East Africa, Chairman of the Alliance for Vulnerable Mission

Published in www.GlobalMissiology.org April 2013

Abstract

Much of African appropriation of the prosperity gospel, it is here suggested, arises from Western missionaries’ wealth-based approach to their task. Research in western Kenya finds African religion to be pragmatic. Meanwhile ‘religion’ in the West has been ‘distorted’ by the challenge of secularism. The notion of ‘the global village’ is considered in a new light. Material dependency, aggravated by peculiar African understandings of causation, is found to underlie much of the relationship between Africa and the West. The desire for wealth from Africa combined with the West’s determination to share can make any critique of the prosperity gospel in Africa to appear nonsense. Critics of the status quo are often handicapped through having a limited understanding on one or the other side of the intercultural gulf. Vulnerable Mission; ministry engaged in by Westerners using the languages and resources of African people, is suggested as a contribution from the West to the solution of the prosperity gospel dilemma.

Introduction

The prosperity Gospel is widely considered to be plaguing the African church. For Westerners – replacing God with money is sacrilege. Many in Africa do not seem to see the problem in the same way. African Traditional Religion is pragmatic – to a degree that it is hard for Westerners to grasp. In Africa religion is often engaged in so as to provide wealth and healing from various ailments. To be told that to do this is wrong, can be confusing to say the least. The orientation to the understanding of a religion as a means to prosperity sets the whole course of life for holistic Africans. Religion is not a gap to be filled at the edges of science as in the West. It has always been understood to be the source of prosperity.

The lifestyle of wealthy Westerners easily becomes the religious ritual of the African.[2] People attend to he who has power – of which financial power is generally a key part. Imitation is a part of how they hope to share in such power. A poor person (unless they master other means to power that I here call ‘magical’) is likely to be despised, or at best ignored. This ‘upward’’ orientation of African life is not based on rational reason (as known in the West). Hence it does not of it-self lead to socio-economic development; but to dependency. An overcoming of this orientation is vital for the future of the African people, and is here suggested can be assisted by what we are calling ‘vulnerable mission’.

The research that underlies this article was carried out largely in western Kenya, especially amongst Luo and Luyia peoples. I use the term ‘African’ because underlying traditions resemble widely throughout the continent, and so as not to make out that the people of western Kenya are somehow unique or peculiarly different from other ‘Africans’.

ATR is Pragmatic

While scholars understand African religion to be pragmatic, the implications of this ‘pragmatic’ nature of belief may be less widely appreciated. When a holistic religion, such as that in much of Africa, is ‘pragmatic’, money easily becomes its main objective.

Religious belief is in Africa less concerned about a means to answer the ‘ultimate’ questions in life than in the West. It is not even a system of belief that is a psychological crutch for the weak – as Christianity has sometimes become in the West. We are not talking about a way of blunting the sharp barbs of crass materialism, or to soften the harsh hopelessness of secularism. Rather, so called ‘religion’ in Africa, is first and foremost about how to put bread on to the table, and how to avoid death.

Sharing the fault for the gendering of endless misunderstandings of African ways of life is the fact that they are given the label in English of ‘religion(s)’. This peculiar term is hardly scriptural. It is a modern term that has arisen in response to the modern era. The modern era has seen science and its advocates swallow-up explanatory systems that used to be a part of life-understanding. Science has become like a robotic monster running havoc through human populations. What were once valid explanatory systems, the West has been told in recent centuries, must no longer be believed. Rather like an obstinate cancerous growth can gradually fill a body organ, strangling it of its original function, so the claims of secularism have squeezed the church in the West into an odd shape and role in the margins. That is into being ‘a religion’; a system that fills the gap between what is evidently scientifically true and certain (arbitrary) limits of human perception.

Western ‘religion’ therefore functions, to put it bluntly, at the peripheries of scientific and objective endeavour. It long ago gave up its claim to sovereignty or hegemony. Not so ‘religion’ in Africa. That is not to say that our metaphor of a contagious ulcer gradually strangling a body organ is necessarily negative. Science clearly has its benefits. The point I am making is that such a growth determines the shape of the remaining organ or in our case ‘religion’ in the West in a way that has not happened in Africa. The rightness or wrongness of this process – I guess is God’s call. Unfortunately, one outcome of all this, given the limitations of ‘translation’, is to falsify the West’s default understanding of what is happening in Africa. The West assumes, simply by default, but it is hard to counter that default thinking, that Africa like the West takes religion almost as a leisure-time pursuit.[3]

The literature so abounds with references to the ‘pragmatic’ nature of African religion that this point does not seem to need emphasising. African churches are oriented to healing. (Healing may be from disease, marriage breakup, business failure, barrenness, AIDs, family tension, poor exams results in school and so on.) Many people join churches as a result of being ‘healed’, often in fear that if they do not take up the faith their ailment will return.

Globalisation and God in Africa

Globalisation has brought a lot of talk of ‘the global village’. The assumption underlying the notion of global village is – that people can nowadays relate globally as easily as in the past they would relate to their fellow villagers. There is another way in which the phrase could also be understood; there is something about people that is inherently ‘village’. This is to say that the kinds of community people can handle; even the kind of community that they are instinctively a part of, is a village community. In that sense – even if you put people into a town or city, they will still behave as if they are in a village. A subset of the towns’ populous become ‘theirs’ and the rest become ‘others’’, but, of interest to us here; others’ that are not ‘theirs’ are assumed to function (broadly) as ‘theirs’ also function. That is, people in one village assume other villages to be functioning in much the same way as their village functions. In another sense, as a result of the need to communicate with people who resemble them, people in one part of the globalised system are really rather restricted to their part (if by other than geographic constraints) of the system. In other words, while you may be able to remove someone’s head from a village, you may not be able to remove a village from their head. Rather than removing village thinking, globalisation has sometimes simply meant that villages operate with less regard to geographical space.

That is to say, in other words again, that the human mind is a limited creature. While it can talk about grand things like a ‘global conscience’, follow through may be more difficult. “… Some people’s provincialism – globalisation – is so hegemonic as not to be seen for what it is” says.[4] The human mind is not designed, it seems, to cope with the massive communication options that are today open to it. In that sense – globalisation is merely an overcoming of geographical distance rather than a breaking down of inter-human cultural rifts.

I say the above in part from sheer personal experience. Personal experience has its limitations – maybe mine is peculiar? But yet, like it or not, personal experience has to be the basis from which everyone interprets all that goes on around them. My experience as a British born male, after living in an African village for two decades,[5] is that it remains very difficult if not impossible to put aside assumptions about my neighbours that are actually carried over from the UK; the foundational understanding of ‘others’ that I acquired in a UK upbringing continues to result in my seeing my African neighbours as if they are more UK-like than they actually are.

The same applies to my observations of the understanding of others from the West. That familiarity that I do have with people’s way of life in my home area in Africa easily has me amazed at the kind of things that fellow Westerners say and do when they come here. They of course do not realise how foolish their behaviour can appear. Locals are often too polite to put them right, or do not know how to in the first place; so incredible can be the foreigners’ antics.

My reason for emphasising this point is to say that much assumed mutual understanding inter-culturally between Westerners and many Africans is more imagined than real. Relationships between people are complex things, and no doubt there are many factors that form them and sustain them. Overriding however in today’s world what binds in relationship between many Africans and Westerners are material considerations, especially material dependency and aspirations on the part of Africans to material gain and Westerners to alleviate poverty.

That this material component of relationships is often not very evident to Westerners is made clear by Maranz[6] and will be examined more closely later in this article. At the moment my point in mentioning it is because it tends to exclude or obfuscate truths of which there may otherwise be more awareness. The ‘truths’ of particular concern to me, are those regarding God and those regarding causation. (There are many other additional reasons for the obfuscation of various truths inter-culturally which I cannot go into in depth in this article – an especially important one being that almost all interaction between Westerners and Africans occurs using western languages.)

I have in Harries[7] explained how, contrary to popular opinion, African understandings of causation can continue to run in parallel with rather than be at loggerheads with scientific views on the same. That is, because understanding based on so-called ‘superstition’ runs in parallel with that of science, scientific processes can be engaged in even by someone whose basic comprehension is far from being scientific. This fact has mystified Westerners. The latter have considered that education ‘ought to’ undercut magical superstitions or fatalistic beliefs. Sometimes it does nothing of the kind, although it can put such beliefs ‘into hiding’. Contrary to Rudolph Bultmann’s notion (that admittedly nowadays seems incredibly exaggerated) that the use of a light-switch is enough to ‘drive away’ pre-rationalistic thinking,[8] ‘magical world views’ (see Harries[9]) need not clash with their rational opposites in major ways. Rather; the two can co-exist.

African understandings of God can be akin to what are sometimes in English known as beliefs in ‘the force’.[10] Despite their adoption of Western terminology for the sake of international recognition, prestige and payment African people’s belief in ‘magic’ may continue.[11] This is recognised by Maranz[12], although Maranz does not go into detail in trying to explain it.

I do not pretend to have a complete understanding of the operations, for example of economics, that I notice occurring around me in an African community. Maranz has done an excellent job of explicating many of these.[13] One important point to learn here though – is that as I as a Westerner who has lived closely to African people using their language for decades have as yet such a ‘limited grasp’. So then African people who often have a much less close association with Western ways of life surely have a limited grasp of Western rationality as it pertains to economics as well as other areas of Western life? I can write more of what is absent in Africa than of what is actually present. To do the latter would any way, for good linguistic reasons, be very difficult using English.[14]

In short, large segments of African people’s thinking about economic and rational processes, are rooted in what could (for want of a better label, because these things I am suggesting are after all largely absent from the English speaking world) be termed to be magical or mystical. I suggest that the actual evidence for this being the case is enormous in the literature, but that such literature is often ignored. I do not have the space to go into the reasons for this in more detail here.

Many African people see wealth as arising as types of blessing. Such blessing is brought about through expressing care in certain relationships, for example one basis of it that I often hear of, is in giving priority care to visitors. The ultimate origin of material wealth is mysterious. The acquisition of a share of it is achieved through relationship, through friendship, prayer, mysterious rituals, and through association with obvious sources of wealth. God is the name given to the link between that ubiquitous mysterious world ‘out there’ and personal prosperity. God’s identity is these days barely distinct from that of Westerners and their ways of life, in so far as these days Westerners are the providers of goods to Africa. This is why western educational institutions are really akin to temples – places at which powerful mystical procedures can be learned using just as powerful and almost as mystical European languages.[15]

Wealth in Inter-cultural Perspective: Between Africa and the West

There has been a long tradition in the West of considering African life to be rooted in poverty. This should not surprise us. African values are not oriented to the ‘rational’ acquisition of wealth as are Western ones. The comparative difference in amount of material possessions is clear. It could be mentioned almost as a ‘by the way’ that confusion on this issue has arisen, as in so many such issues, due to lack of care in translation. To tell an African living in an African community that they are ‘poor’, because they do not live up to certain modern standards is close to being a mockery. Poverty is relative! But the latter has happened, is constantly happening, and is increasingly happening, bringing the very troubling state of affairs in which whole peoples, nations and cultures are labelled as ‘poor’, as if this is the case in some ultimate and not relative way.

I want to attempt to illustrate what has happened in terms of wealth-differentials from the time of the arrival of colonialists on the African continent. My focus is on East Africa and the inland parts of Kenya where this occurred relatively late, just over 100 years ago, although the same pattern is surely representative of much of the continent. I will show what has happened using diagrams, to illustrate my points visually.

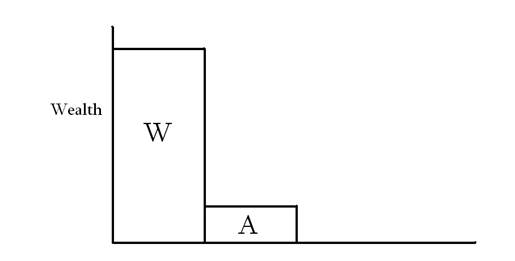

Figure 1: The Wealth Differential Found on the Arrival of Westerners in Africa

In Figure 1, I graphically illustrate that Westerners (W) were in many ways materially much more bestowed than the people they found when they came to the African continent (A). This was not in terms of number of wives, children or cattle – but in wearing clothing, having various machines, technology that enabled them to travel, mysterious objects such as books, enhanced security of food supply, weapons of war and so on. From early on, while there were no doubt those in Africa who were too content to ‘desire’ what the white man brought, many (especially amongst the young) became inquisitive and in due course desirous. Such ‘desire’ on the part of Africans to share in what the West has, has at times been a very powerful force. Contrary to popular wisdom – probably – Brutt-Griffler found that it was the ‘pull’ from the nationals, and not the push from colonialists that resulted in the wide spread of English in British colonies, for example.[16]

A ‘push’ from the West also gradually arose. That is, pressure from the West for Africans to adopt Western things and ways of life. The origin of this was (is) variously in guilt (especially over the slave trade), and well meaning expressions of Christian charity on the part of Westerners who wanted to share with others that which they have which they consider to be superior. Added to this, once the level of desire of Africans built up, especially in the cold-war era, was the need to ‘buy’ allies in the stand-off between democracy and communism.

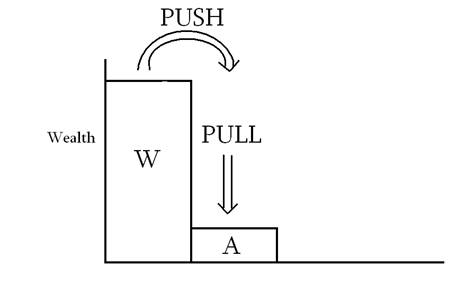

All the above factors together and others in addition, resulted in the beginning of a wealth-transfer process, that continues to date. It is a process, illustrated in Figure 2, that operates on both ‘push’ and ‘pull’.

Figure 2. ‘Push’ and ‘Pull’ of Wealth and Technology Transfer to Africa

African levels of ‘wealth’ began to rise. Western levels of wealth did not go down as a result, perhaps contrary to the expectations of some, due to ongoing advances in technology. Note the ‘magical’ character of the transfer. That is, especially since the 1960s, much of the transfer of wealth has not been on a commercial basis. (Even if it was commercial before that, such would not always have been fully evident to Africans.) That is, Africans did not have to earn the aid they were receiving. It kept coming to them even if they did very little, except perhaps to pray. That is; the means that brought it appeared to be akin to ‘mysterious forces’.

This is the context in which Christianity also was brought to the continent. At the time that African-traditional-religionists were wondering about this unexpected boon to their well being, they received news of a hitherto unknown ‘god’ (God) who died for mankind, and desired that people spend a few hours one-day per week in church to worship him. That was a small price to pay in exchange for the massive material benefits that generation-after-generation was beginning to receive. Among those Westerners who were the most visible in promoting this unexpected material boon were of course Christian missionaries, who often spent years ‘on the ground’ with African people.

A widespread African respect for ‘wealth’, over-and-above that often known in the West, could be articulated at this point. This struck me on reading Mboya’s account of Luo people’s traditional way of life. Those with wealth (i.e. wives, land, cows, etc.) became community leaders, and were expected to become community leaders and were most desired as community leaders.[17] Such association between political power and material power continues to be evident in countries such as Kenya, as evidenced by the massive attention paid to national-level political players by the media, in which those who are not top-politicians seem hardly to get a look in.[18] This is of course the famed ‘patron-client’ system in which the social value of a person is assessed largely by the level of their material sharing. Maranz shows how as a result wealthy people get enormous attention from the general populous.[19]

Enormous respect is in Africa given to Westerners often known in East Africa and beyond as wazungu, that can be translated as ‘people with amazing unfathomable capabilities’. Much of this is concentrated on missionaries, who are the most visible. The understanding of what was going on that made most sense to people in Africa was that most closely related to their innate comprehension – that wealth comes through mystical means – something like those found in the pages of the Bible and continually brought to their attention in the now favoured churches ... The situation that developed is that illustrated in Figure 3 below.

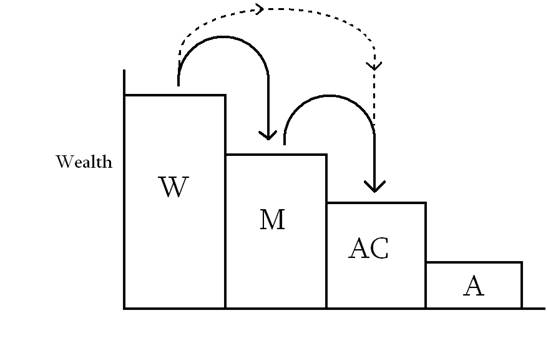

Figure 3. Diagrammatic Representation of Wealth Categories in the Missionary Era

Arrows indicate the direction of movement of wealth.

Differences between the groups represented in Figure 3 may not be to scale but serve to illustrate what goes on. W here represents Westerners, M is Western missionaries who have often taken a drop in living standard through coming to the field. AC is African Christians who have acquired wealth from missionaries and others, whereas A represents those Africans who have rejected much of the Westerner’s ways, including his religion, and thus have acquired relatively little material reward from the Westerner. The arrows show the direction of wealth transfers. The reverse direction to the arrows is paid back in ‘respect’. Note that ‘Christianity’ is in Africa often defined almost as what could in Western-English be called ‘Westernisation’. My intention is not to judge, but is to suggest that not all African ‘Christians’ are truly ‘Christians’ in the theological-sense. Those Africans who reject the West, western Christianity and western languages (A), benefit less from the West than the more compliant AC people.

Telling an African Christian that becoming a Christian is not about acquiring prosperity, it should be clear from the above, can be received as being close to a nonsense. It does not make sense. It is a sacrilege! It contradicts the very basis of faith in superior Western wealth, ways and the gospel that Africans have been given.

The discourse that criticises ‘prosperity gospel’, causes some African people to be puzzled, mystified or distraught. A Ugandan friend once explained that he was at a Christian gathering, at which people were told that God would give them motorbikes. Fresh out of college, with ‘proper’ theology in his head, he stood up and told them that this was a lie. He was not well received, he told me. It was like he was trying to take away the motorbikes – clearly a selfish act!

Trying to find biblical ‘proof texts’ that ‘disprove’ the prosperity gospel, it seems to me, is about as unhelpful as the above. I do not think that you can use the scriptures to ‘disprove’ things like this, because the scripture has to be interpreted. There are of course authoritative interpreters and interpretations – such as that claimed by the Catholic Church, and others. Even they, if their words have a gross mismatch with the evident context, are hard to accept. I believe this is a ‘normal’ principle in Biblical interpretation. It is not to say that the Bible is not authoritative or influential. But it is to say that people will interpret intelligently, and discount options that are evidently wrong, crazy, or clash with their ways of life or thinking in unacceptable ways.

I do not consider prosperity Gospel to be a good thing, however, I agree with Robert Reese, that as things stand it is an almost inevitable outcome of the interaction between African and Western Christians.[20] This is not a healthy position to be in for a number of reasons, of which I can straight away mention two: One is the evident risk if someone comes to Christ in anticipation of material gain, that he or she may again ‘leave’ if that gain proves not to be forth coming. Two, is that this ‘holistic’ approach to the acquisition of wealth is misleading, perhaps deceiving, and not putting people on to a helpful course of ‘development’.

I think the former point is more widely appreciated than the second, so I want to elaborate on the second a little more. I take it in mentioning ‘deception’ above, that one can be deceptive other than by intent. That is, that encouraging African people to continue on the ‘holistic’ route of assuming that it is their prayers that bring the kind of wealth that Westerners know actually comes through the use of a certain kind of reason combined with hard work, is a deception.[21] In short, the ‘system’ is such that it communicates a lie. If this is the case, then Africa as a whole as well as the church is at the moment not being set onto a sustainable course towards modernisation. If the efforts being put into for example education are so misguided, then simply allowing things to continue as they are is to be silent in the face of looming disaster. It is appropriate to act, and to do so as a matter of urgency. The question is; how to act?

Vulnerable Mission

Many, it seems, are unfamiliar with the reasoning presented above. To the contrary, the tendency at this time is still, to see that to give more and more money to Africa, and to continue its domination through foreign languages (by loading them with numerous financial inducements) is the best way forward. The status quo invested in the current blind but charitable system is so enormous, that to try and stop it is like trying to change the direction of a charging ocean liner by ramming it with a small inflatable dinghy.

Fortunately the status quo has its critics. Most of those critics lack insider insights through being rooted in the West, or lack linguistic acumen or contacts to engage effectively in the critical debates occurring in the influential West if they are rooted outside of the West. That is; those critiquing the ongoing constant charitable financial assistance to Africa from the Western end are unfamiliar with African languages and indigenous discourse, but those familiar with African discourses can’t or won’t engage what they know in the debate in the West.

The arguments I present above should have made it clear why many African people choose to remain silent on these issues; either they are happy to accept the ‘magic’ involved, or their own vested interests are in the continuation of the current system, with all the immediate benefits involved especially for people in key positions with a knowledge of English. There are those Africans who are raising their voices; James Shikwati of Kenya[22] and Dambisa Moyo[23] are well known. Of course the missionary moratorium of the 1970s was related to this issue, but the approach advocated by those such as Gatu apparently did not resolve the issue.[24] There are so many vested interests in the ongoing activity of Western mission on the continent, so that to ask missionaries simply to ‘go home’ was impractical.[25]

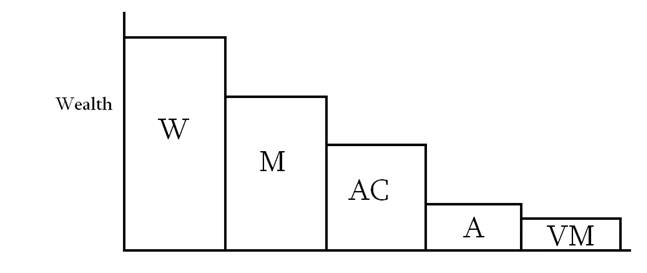

I would agree with Moyo (although she does not write about the church context) that initiative must be taken by Westerners.[26] They hold the power. So what are they, in our case especially Western Christians, to do? I illustrate this in Figure 4.

Figure 4. How to Overcome the Prosperity Gospel

All the positions on the left of Figure 4 (W: Westerners, M: missionaries, and AC: African Christians) appear to A (African) to be hypocritical if they condemn the prosperity Gospel. Being so hypocritical is, I suggest, no small matter to be brushed over. It renders the critic’s voice ineffective in reaching the hearts of many people. In a world full of ‘magic’, using less-than-truths in order to further one’s own interests is not so unusual. Telling others to be ‘poor’ so as to be true to Christ, while personally utilising one’s technological and economic advantages in ministry, is tough.

An alternative option that I want to suggest is VM (Vulnerable Mission). In carrying out VM, a Western missionary deliberately puts himself economically (and linguistically) on a par with or below the local African in their ministry. The suggestion that some Westerners should do this may meet opposition from Westerners who don’t like the idea of living in poverty for its own sake, and from those Africans who might be offended by those who do so. I address these critics by making the following three points:

1. The poverty that I advocate is in ministry and not in lifestyle. That is, that VMs from the West not buy their way into ministry opportunities but build ministry on local languages and resources. This does not mean that their ‘home life’ must be poverty stricken or that they not use more resources outside of their ministry context.

2. Can African people take someone seriously if they are a ‘wealthy’ foreigner, but choose not to use their wealth to boost their ministry? “Covet not” the tenth commandment tells us (Exodus 20:17). Luke 9:3 comes to mind, in which Jesus instructed the missionaries he sent not to carry any resources with which to assist their ministry. Christian ministers have no business looking over their shoulders at others because they are financially better off, I suggest from John 21:22-23. Jealousy is a poor foundation for ministry. In order to make sustainable progress, I suggest, the African must put aside his inclination to jealousy and witchcraft.[27] Westerners need to orient their ministry in such a way as to reach those people who are ready to put these aside.

3. The above will likely be a slow process. But also, I suggest, a very necessary process. Only through the above means can a Westerner really draw near to Africans. Only by the above means can there really be a needed “second touch”[28] for the church in Africa.

Some Western missionaries need to carry out ministries in Africa using local languages and resources, that is vulnerable mission[29]. Some may ask; will African churches accept such an incarnational approach and be ready to engage in ministry with Western missionaries who do not offer material incentives for working with them? The answer to this question remains to be discovered.

Much more could be said regarding both the theory and practice of this style of mission. I have discussed some of this in the above articles (see note 29), many of which have already been published. There may be some opposition from Africa from those who are benefitting from the status quo. Do such have the long-term best interests of their people in mind? Why are they not prepared to accept fellow workers in the church unless paid (directly or indirectly) from the West to do so? How long are one-sided relationships rooted in dependency to continue? Can Christians in the West be said to be serious in their attempts to counter the prosperity Gospel, if at the same time all their activities in connection with Africa perpetuate it? If Western missionaries continue to purchase access into ministry in ‘poor’ parts of the world such as in Africa; do they need to be held responsible for underpinning the prosperity gospel? If ministry cannot be done without western resources, then models of ministry being promoted may be leading to dependence. If ministry can be done without western donors – then it is important that it be done.

Conclusion

A close look at African Traditional Religion, has revealed it to be very pragmatic in nature. It is oriented to the putting of food on to the table, to healing, avoiding death, and to prosperity. Such ‘religion’ responds in a certain way to the coming of Christianity from the West hand in hand with material goods. Christianity having been taken as more lucrative than ‘older’ religions has been widely adopted. African Christianity has (inevitably) adjusted to indigenous forms of understanding. In these ‘indigenous forms of understanding’ the Westerner appears to be akin to God (god) and prosperity an important part of the objective of prayer and worship.

The above position rightly causes some consternation to Christian believers in Western lands. The latter are dualistic in their thinking, and so understand wealth creation as being largely a distinct activity to that of worship to God. The conflating of these two by ‘holistic’ Africans appears idolatrous. Yet the proclivity of the West to combining spiritual guidance with material aid is aggravating this idolatry.

The current status quo in intercultural relations between the West and Africa inside and outside of the church is deeply rooted. It seems not to be very susceptible to alternative forms of thinking. The response suggested in this article to the above dilemma is that the principles of vulnerable mission be adopted by at least some Western missionaries. That is, that some Western missionaries engage in their key ministries using the languages and resources of the people being reached. This applies whether they are engaged in gospel work and evangelism, or in ‘development intervention’. It remains to be seen how receptive African communities will be to Western Christian workers who do not come with the promise of financially uplifting their hosts. Those ‘vulnerable’ missionaries (workers) will become part of the intellectual foundation which will guide inter-cultural mission and communication in general into future inter-cultural relations inside and outside of the church.