ContextualizING the One Gospel in Any Culture:

A Model From the BiBlical Text For a Global Context

Jackson Wu (Ph.D, Applied Theology)

He teaches theology and missiology to Chinese church leaders in Asia.

He maintains a blog at jacksonwu.wordpress.com

Published at www.GlobalMissiology.org, April 2013

Although there is only one gospel (Gal 1:6–8), evangelicals find it difficult both to answer the question, “What is the gospel?” and thus to contextualize it. Many people concur with the idea that Scripture must be central and decisive in contextualization. Moving beyond this basic principle has proven more difficult. Hundreds of books, articles, essays, and blog posts mull over the relationship between the Bible and culture. Despite such labor, evangelicals struggle to develop methods of contextualization that both recognize the Bible as supremely authoritative and reveal God’s truth in ways that make sense in diverse settings, not importing a foreign culture under the guise of the “gospel.”

This essay puts forth a model whereby one can contextualize the gospel in any culture of the world. While presuming an evangelical view of Scripture, it seeks to correct conventional ideas about how to contextualize the gospel. First, we must consider how recent debates concerning “What is the gospel?” relate to our views on contextualization. If the goal is to contextualize the gospel, then a particular question begs answering: How can people agree about contextualization if they disagree on the gospel?

Second, the essay proposes four questions to serve as a framework to understand and present the whole gospel from the whole Bible. The purpose of the model is not simply to “reconcile friends” within theological debates. Christians need a method that has both flexibility and firmness. The gospel does not change; therefore, the framework of the gospel is firm. The world’s cultures are diverse and ever changing; therefore, a method of contextualization needs flexibility. After all, even within the Bible, there is no single prescribed way of preaching the gospel. One could despair of striking the right balance.

Third, we survey Scripture to find how the Bible answers these questions and thus explains the gospel. Within the diversity of answers, missionaries will find considerable overlap with the cultures in which they serve. Fourth and finally, the article illustrates in part how one applies this model in a cultural setting. Although this is the ultimate aim of the essay, it is necessary to give our greatest attention to the preceding interpretive question, “What is the biblical gospel?” A possible “definition” of the gospel is derived after careful observation of the entire biblical canon. The contextualization method proposed also comes from Scripture and does not require people to separate so sharply a biblical and cultural perspective. One does not need to pick a particular theological camp over another simply because s/he does not know how to balance complementary emphases and the themes of the Bible. Therefore, Christians do not need to compromise the gospel by settling for (mere) truth.[1]

Without some method to guide the process, Christians around the world run the risk of two opposite dangers. First, missionaries may communicate the gospel using familiar expressions from their home culture. For example, a missionary from America might uncritically translate a presentation like The Four Spiritual Laws or The Roman Road without consideration as to whether categories like “law” and “guilt” convey the same thing in a place like East Asia as they do in the American “Bible belt.” In this case, gospel presentations can suffer from theological syncretism; that is, theological presuppositions limit the scope of biblical passages one uses to share the gospel (e.g. Romans, Galatians). People confuse the gospel with their own theological tradition. On the other hand, local Christians in less Christianized settings may wrongly interpret the gospel because they use cultural lenses that distort the Bible’s original meaning. In this instance, gospel presentations suffer cultural syncretism. The culture context acts as the authority over the biblical text. People confuse Scripture and culture.

How Do We Agree on Contextualization If We Disagree About the Gospel?

How do we contextualize the gospel when people have difficulty agreeing on what exactly it is? In recent years a flurry of books, articles, and blogs have debated the question, “What is the gospel?”[2] Trevin Wax has compiled an extensive collection of “gospel definitions” as articulated by various Christians throughout history.[3] There seems as much diversity as there is agreement when defining what exactly the gospel is. He broadly summarizes that Christian gospel presentations often recount the story of the individual believer, Jesus, and of creation.[4]

Authors may admit that the gospel at some level contains these elements; however, people either tend to emphasize one aspect of the gospel over another or perhaps they deny altogether that other parts are to be included in the “gospel.” For example, Matt Chandler says, “The Bible establishes two frames of reference for the same gospel.”[5] Specifically, the “gospel on the ground” refers to the call upon individuals to repent and be forgiven of sin because of Christ’s death. The “gospel in the air” links “human salvation to cosmic restoration” as told in the “meta-narrative of the Bible’s story of redemption.”[6]

In slight contrast, Greg Gilbert offers a narrower view of the gospel. He challenges what he calls “three substitute gospels.” He claims, “‘Jesus is Lord’ is not the gospel,” the paradigm “‘creation-fall-redemption-consummation’ is not the gospel,” and “cultural transformation is not the gospel.”[7] He adds, “It should be obvious by now that to say simply that ‘Jesus is Lord’ is really not good news at all if we don’t explain how Jesus is not just Lord but also Savior.”[8] Problematically, he presumes that those who preach the gospel as Jesus’ kingship separate his being Lord from his being Savior, perhaps even “mak[ing] their center something other than the cross.”[9] As a result, Gilbert denies other emphases in order to isolate one strand of thought––the individual sinner in need of forgiveness by the God who judges in wrath.

For many people, the “gospel” is virtually synonymous with justification.[10] In the Gospel Coalition’s book The Gospel as Center, contributors use words like “justification” and “righteous(ness)” at least 385 times. More specifically, a search of the book shows approximately 185 instances of the words “justify,” “justified,” and “justification.”[11] “Righteous(ness)” is used no less than 200 times. Also, the terms “impute(d)” and “imputation” appear about 27 times. Not surprisingly, Romans 3 alone is cited 25 times.

In The King Jesus Gospel, Scot McKnight contrasts yet complements the views already mentioned. He calls such presentations “soterion” in that they reduce the gospel to a message about how an individual gets saved.[12] While not denying the importance of individual salvation, McKnight responds, “Who wants an irreducible minimum gospel? . . . I want the full, biblical gospel.”[13] McKnight suggests that traditional evangelicals “skip from Genesis 3 to Romans 3” when trying to understand and communicate the gospel.[14] He argues that salvation is the result of the gospel, which is the story of how Jesus brings about “the resolution and fulfillment of Israel’s Story and promises,” culminating in the kingship of Christ over Israel and the world.[15] Wax finds no problems with McKnight’s exegesis but worries that “sharp distinctions can sometimes lead to subtle distortions.”[16] Rather than dichotomizing “gospel” from “salvation,” McKnight sees individual salvation as one important aspect of the gospel. He rejects formulations that separate Jesus as Christ/Lord and Jesus as Savior.[17] McKnight attempts to help readers “relearn how to frame the gospel as the apostles did.”[18] Accordingly, he says the apostles frame their gospel presentation not around an atonement theory but more precisely by “the story of Israel.”[19]

In some respect, one can easily see the truth behind each of the perspectives that we have reviewed. It is difficult to see where exactly the problem lies within the gospel debate. It is not so much what is affirmed that is mistaken. Instead, the tension seems to be found in what particular views omit or deemphasize. It is very difficult to debate points of emphasis or to compare one metaphor against another, especially when one camp does not overtly deny another’s view. However, theologians and missionaries must constantly make decisions about what themes should be highlighted and how to relate main ideas to their contexts. Westerners are generally prone towards either-or thinking.[20] When this enters the church, people easily confuse what is true/false with what is primary/secondary. We need an approach to contextualization that takes a both-and approach that helps to relate the assorted building blocks of truth, whether they are white, yellow, black, or brown.

An analogy illustrates the problem we face. Suppose someone asks, “Tell me about your body.” In reply, one might say, “Well, it has four chambers that are full of blood. One half pumps blood through veins. The other half uses arteries.” That would be accurate in a strict though peculiar sense. Depending on one’s perspective, the heart both is and is not the “body.” That is, the heart is an essential part of the body; yet, it in no way constitutes the whole of what is referred to when one speaks of a “body.” Still, such a reply does not really answer what presumably is really being asked. One should describe the body from a broader perspective rather than just one part of it, regardless of how crucial that individual part is to the whole.

Similarly we can ask, “Is the ‘Plan of Salvation’ the gospel?”[21] To say whether the Plan of Salvation is or is not the gospel––either way––requires a bit of unavoidable linguistic gymnastics. Just as the heart “is” the body, so too is the Plan of Salvation. Yet, it is not the gospel in the same way that the heart is not equivalent to the “body.” Most people would not talk as if the heart itself were the whole of the body.

Perhaps it is best simply to say the Plan of Salvation is not the whole gospel. If people only explain “how one is saved,” they do not proclaim the full gospel as the disciples preached it especially as the disciples preached it. “How” one gets saved can easily reduce the gospel to issues of mechanics. One can lose the whole in view of the parts, forsaking the proverbial forest for the tree. However, the gospel also answers other questions besides “how” one is saved. The gospel mainly says something about God himself. It is an announcement about who God is and what he does in history.

That said, if we do not highlight salvation, which is the significance of the announcement, then we also have not preached the gospel. After all, saying “Jesus is King” to someone who knows neither who Jesus is nor the role of a king would hardly be to speak “good news.” It would be akin to claiming “Fred 当老师” to someone who only speaks English. This statement is simply garbled news, being neither good nor bad. Implicit within any such announcement is that the listener understands the significance. Problems come when one only talks about a single aspect of significance (e.g. human salvation), skipping the fundamental announcement of who Jesus is and the fact that God’s glory will permeate his new creation. Otherwise, we de facto make the gospel centered on humans. Along this line of thinking, once one gets “saved,” there is not much left to say that compares in importance.

A hypothetical scenario may explain why it matters whether one skips the announcement and goes directly to salvation. Perhaps, someone might say, “That couple just married. They slept together and now she is pregnant!” What happens if we overlook the first part? We are left hearing only about a function or activity robbed of its proper relational context that gives significance to the benefit or results. Announcing the pregnancy apart from the first part may even sound unbelievable or scandalous, depending on one’s context (e.g. Mary’s pregnancy with Jesus). While intimacy and children are wonderful blessings of the marriage, they still do not make up the whole of what it means to be married.

Finding the Whole Gospel in the Whole Bible

In order to agree on how to communicate the gospel, we must find common ground as to the content of the gospel. People should be able to agree on the big ideas that shape the biblical gospel, even if there is disagreement about smaller points of emphasis and verbiage. However, a fundamental problem plagues the “What is the Gospel?” debate. Authors cannot seem to agree on which Scripture passages to use when defining the gospel. Not surprisingly, the texts one chooses will determine the major themes and scope of one’s gospel presentation.

Greg Gilbert, for example, says we should not limit our understanding of the gospel to a word study on the word “gospel” since there are many passages that do not use the word but surely convey the message. Instead, he suggests using Romans 1–4 to find a “shared framework of truths around which the apostles and early Christians structured their presentation of the good news of Jesus.”[22] Gilbert’s argument is problematic. Simply because one should not limit one’s understanding of the gospel only to explicit references of a word, this does not mean that such passages are not essential for defining the explicit contours of the gospel. Such passages are critical for making sure we are not overly selective in emphasizing on aspect of the gospel over another. We should be wary of defining the gospel in a way that does not echo the usage of the word “gospel” in the most explicit contexts. When Gilbert examines Rom 1–4, his oversight causes him to skip over Paul’s single most explicit summary of the gospel in the letter. In Rom 1:1b–4, Paul writes that he is “set apart for the gospel of God, which he promised beforehand through his prophets in the holy Scriptures, concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh and was declared to be the Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord.” Unfortunately, Gilbert calls Rom 1:1–7 merely Paul’s “introductory remarks [after which] Paul begins his presentation of the gospel by declaring that ‘the wrath of God is revealed from heaven,’ (v. 18).”[23]

Other popular evangelical books do not focus on biblical passages that directly use “gospel” language.[24] In The Gospel as Center,[25] Paul’s summaries in Gal 3:8 and 2 Tim 2:8, Luke’s accounts of Paul in Acts 13:32, 14:15, and OT texts like Isa 40:9, 52:7 are never discussed. Also, 1 Cor 15:1–8 is mentioned briefly in only two places.[26] Romans 1:1–4 is cited once.[27] Neither Rom 1:1–4 nor 1 Cor 15:1–8 are used in the chapter “What is the Gospel?”[28] In The Explicit Gospel, Matt Chandler acknowledges the importance of perspective and of using the whole Bible in order to perceive the whole gospel.[29] His usage of 1 Corinthians does go beyond that found in The Gospel as Center.[30] Yet, explicit gospel summaries such as Rom 1:2–4, Gal 3:8, 2 Tim 2:8 and others are entirely left out of the book.[31]

Paul’s sermons in Lystra and Athens (Acts 14, 17) further complicate questions about what is the gospel and how to contextualize it. His message in a purely Gentile context seems to contrast sharply with his presentations elsewhere among more Jewish audiences.[32] Rather than overtly citing Jewish Scripture, Paul is more philosophical, pointing to nature in order to identify the one true God.[33] Despite his initial presentation, it is informative that “Jewish elements” of the gospel are pervasive in letters to Gentiles, such as in Romans, 1 Corinthians, and Ephesians. How is one to grasp Paul’s view of the gospel and contextualization given such contrasting evidence? Even though Paul does not explicitly cite Old Testament texts, does he have a framework by which he presents the gospel in Lystra and Athens?

A Biblical Contextualization Requires a Biblical Theology

By examining a range of texts throughout the cannon, one sees a pattern emerge whenever biblical writers discuss the gospel. One also discovers how to relate the complementary answers given to the question, “What is the gospel?” In addition, it becomes more apparent how one might balance these competing perspectives.

There are advantages to seeking common ground between the various “gospel” texts rather than restricting ourselves to a “canon within a canon.” First of all, people guard themselves from provincialism and rancorous debate when they acknowledge that other views have legitimate biblical support. One need not pose false either-or scenarios wherein the different theological camps feel their position is being threatened. Second, we increase the possible number of outcomes that could be gained in the contextualization process. After all, one is not limited to a particular theme prominent within a narrow set of texts. As a result, people can draw from a rich array of images, and interweaving motifs that span the canon.

Finally, this contextualization methodology is less arbitrary and even gains credibility in that it begins with the entire biblical text in view. The resultant gospel contextualizations can fairly claim a degree of balance and comprehensiveness because it accounts for the diverse biblical answers to the question, “What is the gospel?” This approach also does not presuppose that those in the non-western churches will develop theologies that emphasize as strongly that which Luther, Calvin, or Edwards stressed. Majority world theologians and pastors can remain firmly biblical without denying the insights of history. By analogy, one could compare the books of Genesis, Ecclesiastes, Ezekiel, Luke, Galatians, and 1 Peter. Their message, themes, tone, and style vary drastically. Their theologies are different but without contradiction.

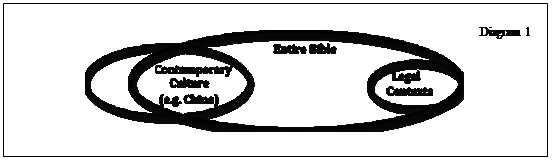

Diagram 1 illustrates the importance of using the full biblical context, the entire canon, in order to do contextualization.[34] Contextualization is more than bridging particular biblical ideas to a culture; it requires us to find where the major themes throughout Scripture overlap with a contemporary culture. If people only use a narrow set of verses and themes to evangelize, then a few consequences naturally follow. First, contextualization is reduced to finding communication “bridges” from a particular motif. Second, depending on where people are from, non-Christian listeners may have to convert culturally in order to accept the gospel presentation being conveyed. Take China as an example. If Chinese listeners hear a traditional law-oriented gospel presentation, they must use categories of thought typically not native to Chinese thinking. Instead of thinking in terms of face, relationship, and collective identity, the traditional western gospel message focuses on legal guilt and is individualistic. On the other hand, when one draws from a fuller biblical theology (not merely systematic theology), then contextualization is not only more holistic but also more biblically “faithful” and culturally “meaningful.”[35]

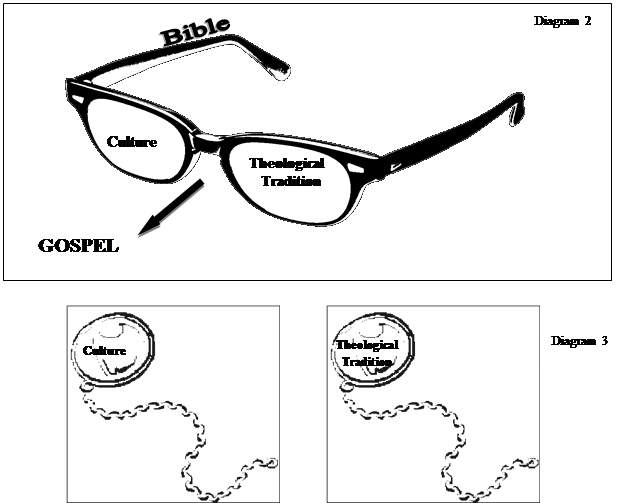

Diagrams 2 and 3 depict the way Christians perceive the gospel. All people see the gospel through a cultural lens. Additionally, one’s theological or denominational background shapes how the gospel is understood. Each perspective has limitations. The entire Bible provides a framework through which to balance these two lenses. If not careful, a person will use a monocle by which one sees the gospel through the narrow, lone lens of one’s culture or theological camp.

Therefore, it is biblical in only a narrow sense to limit the gospel to one single idea, namely individuals being saved from the wrath of God through Christ’s death. Although a gloriously wonderful truth, it must not be separated from the totality of what Christ accomplishes. Focusing on this solitary achievement is like one seeing the sun’s light refracted from a tin roof in contrast to one being blinded by the sun when looking at it directly. For all practical purposes, Gilbert refracts the glory of the gospel when he claims that “Jesus is Lord” and “Creation-Fall-Redemption-Consummation” are not the gospel.[36] We must not fragment the gospel with false dichotomies. He presumes that other perspectives “marginalize” the cross.[37] The assumption is unfounded. In fact, he may give a strawman argument. He explicitly addresses “evangelical Christians,” yet does not cite anyone who actually makes the cross to be less central as he accuses.[38]

We therefore see other reasons why it matters to root contextualization in biblical theology, not merely traditional systematic theology. By limiting the gospel to those texts that teach justification by faith, one threatens to divide the church into needless controversy. In addition, missionaries defend a single expression of the gospel as if that expression was the totality of the gospel. Consequently, the work of missions is greatly hindered. David Sills aptly puts it this way: “Because most missionaries and preachers want to avoid anything that would alter the gospel message, they shrink back from the hard work of contextualization. However, if one does not contextualize, he is doing just that––changing the gospel. He becomes a modern-day Judaizer. He is in effect telling his hearers that they must become like him to be saved.”[39]

In addition, if we are not careful, we unintentionally distort the truth. Consider the repeated argument made by Gilbert:

It should be obvious by now that to say simply that “Jesus is Lord” is really not good news at all if we don’t explain how Jesus is not just Lord but also Savior. Lordship implies the right to judge, and we’ve already seen that God intends to judge evil. Therefore, to a sinner in rebellion against God and against his Messiah, the proclamation that Jesus has become Lord is terrible news. It means that your enemy has won the throne and is now about to judge you for your rebellion against him. . . . Just like the proclamation that “Jesus is Lord” is not good news unless there is a way to be forgiven of your rebellion against him, so the fact that God is remaking the world is not good news unless you can be included in that.[40]

At surface level, there is no problem in what Gilbert says. However, using biblical language in this way obscures if not unwittingly undermines what the Bible says. No doubt, it is a matter of perspective whether one calls this “good” news. Nevertheless, in Scripture the gospel remains “good news” not matter who are its hearers, Christian or non-Christian. In other words, the gospel is good news not only when spoken to Christians but also when speaking to non-Christians. For example, when directly speaking to non-believers, Paul in Acts 13:32, 14:15 explicitly tells his hearers that he is preaching the “gospel,” (cf. Mk 1:15). The gospel is good regardless of what God’s enemies think. The gospel is no less good simply because someone denies God exists (i.e. atheists) or hates the biblical God (i.e. Hitler). Unfortunately, by limiting Christ’s “lordship” merely to “judging evil,” Gilbert’s message makes it more difficult to understand passages where Paul overtly equates Jesus’ Lordship and the gospel. Paul says,

. . . if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved. . . . For the Scripture says, “Everyone who believes in him will not be put to shame.” For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek; for the same Lord is Lord of all, bestowing his riches on all who call on him. For “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.” How then will they call on him in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in him of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone preaching? And how are they to preach unless they are sent? As it is written, “How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the good news!” But they have not all obeyed the gospel. For Isaiah says, “Lord, who has believed what he has heard from us?” So faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ. (Rom 10:9–16)

According to Gilbert’s logic, Paul essentially says that one is saved by confessing Jesus as judge. Further, Rom 10:12 becomes difficult to understand since, according to his logic, our “enemy” (Gilbert’s term) bestows his riches on us sinners.

In other words, if we get contextualization wrong, we mistake the gospel and bring harm to our listeners by setting up a fractured theological framework, making it hard for them to interpret Scripture after the initial presentation. Consequently, new believers naturally build upon the initial categories that are presented to them under the name of “gospel.” For example, if evangelists only stress “law” and “judicial righteousness,” new believers will constantly try to fit their theology and experience in these terms. If we limit lordship to judgment, then readers are not able to make sense of numerous passages that celebrate Christ’s lordship. They will not see that “lordship” language more broadly connotes kingship. Jesus is the King who frees us from the reign of sin and death (cf. Rom 5:17–6:23).

Similarly, many people, including Gilbert, restrict God’s “righteousness” to refer to his holiness to judge evil.[41] Demarest’s contextualization echoes Gilbert. Demarest goes even further, claiming that “the holy and righteous character of God” is an “obstacle” to salvation.[42] Again, this reductionistic contextualization directly contradicts biblical writers like David, who appeals to God’s righteousness in order that God would save him (cf. Ps 51:4; 71:2; 143:1, 11). In short, these contextualizations of the gospel mistakenly reduce the meaning of “Lord” and “righteousness” to that of “judge” and “angry against sin.” These ways of speaking may be true from a particular vantage point. They may evoke a response from listeners.[43] However, these contextualizations do not represent a holistic biblical theology and ultimately stunt the growth of the believer.

A Flexible Method to Frame the Biblical Message

We need a method of contextualization that is both firm, flexible and based on a distinct biblical framework. A framework maps the contextualization process. Maps are inherently abstract but very practical. The biblical text provides necessarily firm boundaries for any contextualization method. Scripture guides the process, builds a framework for gospel presentations, thus designating the essential gospel message.

Furthermore, one’s methodology needs to be flexible to fit both the biblical text and the cultural context. There is one gospel but many methods of expressing it. Flexibility comes from the overlap of multiple contexts. One the one hand, different passages talk about the same topic or share common motifs. Within a single passage, multiple images and concepts may be used, such that Peter can say Christ is a “cornerstone,” and “whoever believes in him will not be put to shame,” for Christians are a “chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation,” yet are “sojourners and exiles” in the world (cf. 1 Pet 2:6–11). On the other hand, various ideas in Scripture overlap with the values and categories of thinking found within contemporary cultures. For instance, there are people in Scripture as in modern times who uphold family honor, who struggle with hypocrisy, or who have ethnic/national prejudice.

How does one utilize the similarities found between the ancient text and the contemporary context? First of all, it should be clear that resemblance does not mean equivalence. In different periods and places, what it means to “lose face” will vary. Also, one cannot expect to remain an effective communicator if we consistently talk using abstract jargon. Therefore, it may not be helpful to always use anthropological terms like “honor-shame,” “guilt-oriented,” “collectivism” and “individualism.” Instead, people can use the symbols within a society that convey these concepts.

Take “honor and shame” for example. Reputation, name, job title, gender as well as cars, clothing, and salary can indicate one’s social status, thus honor and shame. Likewise, we could ask what things people deem valuable, what topics do they like to talk about, or even what do they fear or boast in. In China, while many idioms use the characters for “honor” (荣) and “shame” (辱), it would be more common to convey these concepts using terms having to do with “face” (e.g. 面子, 脸) or someone’s name (名字). Of course, it would be helpful for people to consider nuances between words in a language. For example, mianzi and lian both mean face but carry slightly different but important connotations.[44] By attending to these subtleties, one can more effectively convey biblical truth.

Countless visual and verbal markers represent honor and shame across diverse cultures and subcultures. Consider Paul’s complaint in Gal 4:17 about those who trouble the Galatian church, “They make much of you, but for no good purpose. They want to shut you out, that you may make much of them.” How do people around us today “make much of” others? Maybe this means sitting in a particular seat at a banquet (cf. Luke 11:43). In China, this means the seat directly facing the door of the room. Or perhaps, we curry favor with someone by pushing “like” on her Facebook page or mentioning her in a Twitter message. A person in America may not use words like gaining or losing “face” but they might talk about “people pleasing” or “trying to look good in front of others.”

The Gospel Answers Four Key Questions

In debates about the “gospel,” a few contrasts are frequently made. On the one hand, people present the gospel in either a propositional or a narrative fashion. On the other hand, these gospel presentations may also be described as either “soterion” (narrowly focused on individual salvation) or “kingdom” oriented (more broadly centered on God’s rule over creation). Therefore, conventional evangelism tools like The Four Spiritual Laws or The Romans Road represent a propositional, soterion approach. Perhaps, The Story could be called a narrative, soterion presentation.[45] The gospel in McKnight’s The King Jesus Gospel and N. T. Wright’s How God Became King could be characterized as narrative and mainly oriented on God’s kingdom.

These two sets of categories (propositional/narrative and soterion/kingdom) should not be confused. When talking about using propositions versus narrative, one in fact speaks of the scope from which one most directly constructs a gospel presentation. Obviously, The Roman Road narrowly selects a few verses from the book of Romans and can be reviewed in a matter of minutes. They act as doctrinal statements demarcating what beliefs one must have to become a Christian. A narrative approach is typified by Chandler’s “gospel from the air” previously mentioned and in the works like Albert Wolter’s Creation Regained[46] or The Drama of Scripture: Finding Our Place in the Biblical Story by Craig Bartholomew and Michael Goheen.[47] This approach emphasizes the richness and integrated nature of the biblical story. Summarizing the whole Bible in a matter of moments leaves much to be desired.

When contrasting a soterion and a kingdom-focused presentation, it is the breadth or scope of God’s work and mission that is the main issue. In a gospel presentation, how much should we talk about concerning what God achieves through Christ? Should the scope be narrow, oriented around individual salvation? Or, does the gospel necessarily include what God did in all of redemptive history for the entire cosmos?

In the following sequence, which statement is most basic or essential?

1. Christ is king.

2. [Why?] Christ defeated sin and death.

3. [Therefore] The world can be freed from bondage and receive blessing.

4. [Therefore] We must be loyal to him.

Which statement is the gospel? Obviously, they are inseparable. To say any of them requires the others in order for them to have their intended significance. Yet, are we to reduce this message into discrete statements whereby the others are not the gospel message?

Much of evangelicalism focuses on mechanics (how something works) rather than purpose (why it is so).[48] Therefore, people reach an impasse as to what is most “fundamental” in theology debates (e.g. atonement theories, guilt vs. shame, etc.). One camp speaks about the parts that make the whole work. Another may focus on the final goal. How does one define “fundamental”? By a thing’s parts or by its purpose? From different perspectives, the answers could vary according to the context of the conversation.

To contextualize the gospel like Paul did, we must interpret the Bible the way Paul did.[49] People like Richard Hays (following J. C. Beker) highlight the point that Paul’s gospel seems to have parts that are both constant and contingent.[50] The former refers to aspects of the gospel story like Jesus’ death and resurrection. The latter highlights those elements of Paul’s message that are given emphasis or shaped by the needs of Paul’s context. I suggest four questions that help us to organize those constant and contingent parts.

The gospel answers four questions. The exact wording of each question may be adjusted depending on the context.

First, who is Christ? (or, Who is God?)[51]

Second, what has Christ (or, God) done? (i.e. What kind of a God is he?)

Third, why does this message matter?[52]

Fourth, how should we respond?

One can speak about the gospel with reference to God the Father or to Christ the Son. We do not want to divide the Father and the Son; rather, the point being made here is that the biblical writers at times interchange their language. Accordingly, they sometimes speak about what “God” has done while, at other times, about what Christ has done. First, I will explain the rationale for each question. Then, we will see how Scripture answers them.

Who is Christ?

The first question––who is Christ––is most fundamental. We could say both that Christ is “Savior” and that he is “Son of God.” Likewise, God is Creator and King. This initial “who” question establishes the context and credibility for the answers to the following question. Knowing who Christ is will affect how one understands his actions (Question 2), why he is significant (Question 3), and thus how we should respond (Question 4). Wherever one looks in Scripture, the gospel answer some or all of these questions: Who? What? Why? How?

Reflecting upon these four questions can help to reconcile seemingly disparate answers to the question “What is the gospel?” The range of the questions ensures balance. The sequence also helps to protect against the tendency to make the gospel human-centered rather than God-centered. Understanding and thus explaining the doctrine of salvation, which is especially stressed in question 3, will depend on understanding the kind of God this is who saves and how he has accomplished this rescue. The preaching and receiving of salvation should result in worship: soteriology for the sake of doxology.

It is common to hear people say that we should talk long on judgment in order that people might grasp the significance of God’s grace; [53] however, even this is still not the beginning. In beginning to understand the gospel, we must first see God as worthy of all honor (cf. Gen 1).[54] He becomes the measure of all honor, standard of morality, and source of delight. It is only in this context––the presence of God––that we understand shame, thus the wretched wrongness of sin. Therefore, we must recognize who God in Christ is as the real starting point of the gospel.

The most basic content of the gospel answers the question “Who is Christ?” or “Who is God?” John Piper captures the point this way: “God is the gospel.”[55] The goal of the gospel is to glorify God. It is sometimes called “the gospel of the glory of the blessed God” (1 Tim 1:12) and “the gospel of the glory of Christ” (2 Cor 4:4). Thus, the gospel above all aims to show the worth and greatest of God. Indeed, this is the ultimate goal of God himself.[56] Many people would no doubt agree that God wants glory (even if they do not rank this as God’s highest priority). One might say this is an obvious assumption; yet, there is a possible problem with assuming that God’s glory is central. The problem is not simply that it is assumed; rather, one tends to forget how much God’s glory matters for theological thinking and practice. We become as fish that have little or no awe of the grandeur of the ocean, awakened only briefly by the realization that we might be removed from it.

Notice how Scripture talks about the human problem (i.e. what we mean when we say “sin”). Genesis, for example, does not start with human sin. Rather, Gen 1–2 establishes a God centered context by which we see God as Creator and King. Humans bear his image. Only then does the fall of humanity in Gen 3 make sense. Paul likewise talks about the human condition. In Rom 1, he makes no mention of “law” or “sin.” Rather, he describes human “unrighteousness” in this way: “They did not honor him as God or give thanks to him,” they “exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man. . . . They exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator,” and “they did not see fit to acknowledge God” (Rom 1:21, 23, 25, 28). Notice that Paul defines the human problem in reference to God’s honor. God’s own glory is the measure of human shame (cf. Rom 1:24, 26–28). Romans 3:23 is perhaps the most famous verse about sin in the Bible. It is easy to forget that Paul defines sin in terms of God’s glory: “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” Furthermore, one should not overlook Rom 2:23–24, “You who boast in the law dishonor God by breaking the law. For, as it is written, ‘The name of God is blasphemed among the Gentiles because of you.’” The main verb of the sentence is “dishonor” [avtima,zeij], not “breaking the law,” which actually is a prepositional phrase [dia. th/j paraba,sewj tou/ no,mou]. Fundamental to sin is the dishonoring of God; breaking God’s law is just one expression of sin.[57] In short, we should preach long on the glory of God; only then will people understand the meaning of sin and the significance of salvation.

One final clarification is needed. In making known the knowledge of God, one should not think of his qualities in terms of mere abstraction––such as his omniscience, oneness, holiness, eternality, etc. This is the standard way that the doctrine of God is taught in systematic theology classes. Instead, a better approach is to talk about the ways God has revealed himself in history. How does God describe himself? He is often spoken of as the one “who made heaven and earth” (cf. Ps 115:5; 124:5), the “God of Abraham” (cf. 2 Chron 30:6; Neh 9:7), “the God of Israel” (cf. Exod 5:1; Ezek 8:4). God is the God who works in history. By speaking in this way, we also protect against making sin and salvation abstract or otherworldly. Sin is relational and God’s people long to be resurrected with Christ, living in a new heaven and new earth (cf. Acts 24:15; Rom 8:17–24; 1 Cor 15:20–58; Rev 21:1).

What Has Christ/God Done?

God’s actions flow from who he is. They reveal his character. It is insufficient to say what he has done if we misunderstand who he is. The phrase “He saved me” can have significantly different connotations depending on whether “He” refers to a firefighter, a doctor, my king, or my clan’s longtime enemy. Likewise, “He died instead of me” does not sound the same in every circumstance. Perhaps, I am talking about a patsy, one who is unjustly blamed on my behalf. Or, “He” happened to be at the place I was supposed to be, except I ran late on that particular day. Consequently, he took my seat on the bus when it crashed. The quality of an action and his/her character is determined in light of who they are. Do they have the right to act that way? How do other people in their position behave? Do we find anything typical or extraordinary?

Furthermore, what someone has done in the past provides a basis for believing what he will do in the future. This premise is the basis of Paul’s repeated point in Rom 5:6–10,

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly. For one will scarcely die for a righteous person––though perhaps for a good person one would dare even to die––but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us. Since, therefore, we have now been justified by his blood, much more shall we be saved by him from the wrath of God. For if while we were enemies we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son, much more, now that we are reconciled, shall we be saved by his life.

In Hosea, God’s actions reveal the kind of relationship he has with his people: “When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son” (Hos 11:1). The Lord continues by recounting the way he has loved his people, making clear who God is so that people can clearly see their own shame (cf. Hos 11:1–12; 13:4–5; Amos 2:9–11). If we want our listeners to glorify and love God, grasp the weight of sin and salvation, and so have faith in the promises of God, then our gospel presentations will recall the works of God in history. God’s promises will not sound like good news if people do not think he is trustworthy.

Why Does This News Matter?

Why does this message about Christ matter? This question needs little elaboration since theologians and pastors traditionally lay the greatest stress on this topic. In a word, the gospel is the message by which sinners are saved. Naturally, evangelism in its fullest sense requires we talk about sin in some form or fashion. This story is not complete without making clear God’s response to sin. This response takes two forms. On the one hand, God will judge a sinful world. As Paul says, there will be a “day when, according to my gospel, God judges the secrets of men by Christ Jesus” (Rom 2:16). In Rev 14:6–7, when the angel proclaims the gospel, he announces God’s judgment: “Then I saw another angel flying directly overhead, with an eternal gospel to proclaim to those who dwell on earth, to every nation and tribe and language and people. And he said with a loud voice, ‘Fear God and give him glory, because the hour of his judgment has come, and worship him who made heaven and earth, the sea and the springs of water.’” On the other hand, judgment has a positive side. In judging his enemies, God brings salvation to his people and righteousness to the earth. Accordingly, Isaiah writes,

Shower, O heavens, from above, and let the clouds rain down righteousness; let the earth open, that salvation and righteousness may bear fruit; let the earth cause them both to sprout; I the LORD have created it. Woe to him who strives with him who formed him, a pot among earthen pots! Does the clay say to him who forms it, “What are you making?” or “Your work has no handles”? (Isa 45:8-9).

In fact, the entire Bible reveals this pattern where God brings salvation through judgment.[58]

Although the gospel means “good news,” it is not always evident to people why it is good news. One should recall that different things can sound good in one culture but go unnoticed in another context. This fact does not make it less “good.” This dynamics gives us room to adjust the way we present the gospel. We desire for people to see all that is good in the gospel. However, this takes time. Thus, we must take steps so that people can see, as much as is possible, what is good in this news. By drawing from the entire Bible, not simply our favorite texts, we gain a balanced perspective on salvation. By not developing a “canon within a canon,” one identifies what are the major themes or motifs God uses to explain salvation.

We do not want to confuse what is most central with true but less emphasized blessings. For example, God will ultimately heal our broken bodies, however, laying stress on physical healings is not the most common way the writers talk about salvation. By majoring on what is a minor theme, one can mislead people concerning the essence of salvation. A more prominent way of speaking about salvation is to speak of glory and shame. Christ is the “hope of glory” (Col 1:27). He will bring “many sons to glory,” (Heb 2:10) for all who believe in him “will not be put to shame” (1 Peter 2:6–7; citing Isa 28:16). This language echoes the psalmist, “On God rests my salvation and my glory; my mighty rock, my refuge is God,” (Ps 62:7).[59]

How Should We Respond?

The gospel is not merely information; it is a command. Evangelicals have rightly emphasized the point that the gospel necessitates a response. This is one of the strength’s of Gilbert’s book. Paul proclaims in Lystra, “We also are men, of like nature with you, and we bring you good news, that you should turn from these vain things to a living God” (Acts 14:15). Jesus himself preached, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel.” In some places, we find that people should “obey the gospel” (Rom 10:16; 2 Thess 1:8; 1 Pet 4:17). Thus, a few expressions are used to convey humanity’s appropriate response to the gospel. These include faith, repentance, and obedience.

One should not confuse the gospel and the response. Gilbert and DeYoung make a critical logical mistake when discussing Mark 1:15, “It is wrong to say that the gospel is the declaration that the kingdom of God has come. The gospel of the kingdom is the declaration of the kingdom of God together with the means of entering it. Remember, Jesus did not preach ‘the kingdom of God is at hand.’ He preached, ‘The kingdom of God is at hand; therefore repent and believe!’”[60] They misquote the end of the verse. It should say, “. . . repent and believe the gospel.” The point being clarified is straightforward. The content of the gospel and the response to the gospel are separate ideas and should not be collapsed into one. Even if they are integrally related, the words and grammar prove the distinction. Gilbert and DeYoung assert the gospel itself includes the fact that we are saved if we respond with faith and repentance. However, if this is Jesus’ meaning, then he commands something like this: “repent and believe that you can repent and believe the truth that you can repent and believe . . . .”[61] If we must believe the gospel yet that gospel is a conditional statement wherein we are to believe the gospel, we end up with a vicious cycle. More precisely, the “gospel” as the Bible uses the word is not a “how-to” concept expressed in the form of a conditional sentence (i.e. “If . . . then . . .”); rather, it is a declaration that implies a command.[62]

The Gospel in the Biblical Context

How does the Bible answer these four questions? This section summarizes and highlights the range of possible answers included within Scripture. An important point is reinforced: these four questions are not arbitrary. They arise directly from observing the texts that most explicitly discuss the “gospel.” Given the breadth of texts and themes, a thorough exegesis of the relevant passages is impossible. Still, one should intentionally observe passages that use explicit gospel language. We begin with a summary statement of the gospel.

The gospel is the good news that God has accomplished his creation purposes by fulfilling his promises given through Israel. In particular, the gospel narrates how God reigns over all nations through Jesus Christ whom he resurrected thus defeating his enemies, the last being death. As a result, Jesus reconciles us to God the Father by redeeming us from slavery to sin, which is any idolatrous power that corrupts our desires and condemns us to everlasting shame. God will recreate the world in which the human family receives, reveals, and rejoices in God's glory. In response, God commands all nations to repent of their rebellion. Any who give their allegiance to Christ will not be put to shame.

The apostles had no set formulas to suit for every person in any circumstance. We share one gospel but use a variety of methods, stories, themes, and expressions. Among Jews and God-fearing Gentiles, Paul more explicitly highlighted the elements of the gospel like the Abrahamic covenant and promise of David’s having a descendent that would rule forever over the nations. However, among those Gentiles who were not sympathetic to Judaism, Paul takes a different approach without changing the basic elements of the gospel. The book of Acts explicitly tells us that Paul preached the gospel in Lystra, Athens, and elsewhere (cf. Acts 14:15, 21; 17:18).

The Bible gives a number of complementary answers to each question. One may use a variety of metaphors and stories to make the gospel clear for different listeners. Listed below is one biblically faithful way to answer these questions that is also easy to remember.

1. God through Christ reigns over all nations.

2. God resurrected Christ, who died for human sin.

3. God through Christ reconciles humanity’s relationship with God, with other people, and with the world.

4. All people from every nation are commanded to repent and give their loyalty to Jesus as Supreme and Saving King of the world.

The point must be reemphasized: These statements make up a brief outline of possible answers. The person who shares the gospel must explain what these words mean. Listeners may not share the speaker’s cultural, religious, or educational background. One cannot assume others understand the words and concepts being used.

Using one set of themes and Scriptures does not mean we deny the validity of other concepts and texts. One desires to be both faithful to the Bible and clear for our friends. There are other possible ways of explaining the gospel of salvation. For example, consider the question “Who is Christ?” As the heart of the question is who deserves our loyalty. The Bible gives a number of answers. God is Creator, King, Father, Shepherd, Master, Savior, and Husband to his people. The key idea highlighted here is God’s supremacy. He is the highest authority who sovereignly rules over all things with love, wisdom, and righteousness. God created the world to be a kingdom in which he manifests his own glory and so is worshipped by humans, whom he created to reflect his rule over all things.

What gospel texts answer the “who” question? To begin, the “gospel . . . concern[s] his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh and was declared to be the Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord, through whom we have received grace and apostleship to bring about the obedience of faith for the sake of his name among all the nations” (Rom 1:1, 3–5). It is not a side issue that Jesus is David’s son, as evidenced by Paul’s choice of emphasis when he succinctly recalls the gospel in 2 Tim 2:8, “Remember Jesus Christ, risen from the dead, the offspring of David, as preached in my gospel.” Michael Bird links the “who” and the “what questions: “Yet, whereas 1 Corinthians 15:3–5 focuses on the work of Christ as the key ingredient of the gospel, Romans 1:3–5 centres on the identity of Jesus Christ as the content of the gospel.”[63] Martin Luther similarly states the gospel in this way: “The gospel is a story about Christ, God’s and David’s Son, who dies and was raised and is established as Lord. This is the gospel in a nutshell . . . .”[64]

As previously observed, Paul later equates the statement “Jesus is Lord” and the gospel in Rom 10:9, 14–17 (cf. Acts 10:36; 1 Cor 12:3; Phil 2:11). The apostles “did not cease teaching and preaching (euvaggelizo,menoi) Jesus as the Christ.” (Acts 5:42). One sees a consistent pattern whereby an apostle’s core message is summarized by the point, “Jesus is the Christ” (cf. John 20:31; Acts 3:20; 9:22; 17:3, 7; 18:5, 28). In 1 Cor 15, “the gospel [Paul] preached” explains that “Christ” is the “last Adam” who “reigns” as king over his enemies (1 Cor 15:1, 3, 20–28, 45). Also, when Paul explains the “gospel [preached] beforehand to Abraham,” he proceeded to make the point that Jesus was the offspring through whom the Gentiles would be blessed (Gal 3:8, 14, 16). Put succinctly, the gospel announces that Jesus is the Christ, David’s son, Israel’s King, thus the Son of God (cf. John 1:49).[65]

In the Old Testament, we see a similar pattern where the Greek words for “gospel” to “to announce the gospel” aim to highlight who God is. In Isaiah 52:7, which Paul quotes in Rom 10:15, one reads, “How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him who brings good news [euvaggelizome,nou], who publishes peace, who brings good news [euvaggelizo,menoj] of happiness, who publishes salvation, who says to Zion, ‘Your God reigns.’” God is king. Isaiah 40:9 makes a similar announcement, “Get you up to a high mountain, O Zion, herald of good news [trfbm; o` euvaggelizo,menoj, LXX]; lift up your voice with strength, O Jerusalem, herald of good news [trfbm; o` euvaggelizo,menoj, LXX]; lift it up, fear not; say to the cities of Judah, ‘Behold your God!’” In context, Isaiah proclaims that it is the “Lord God” [hwhy ynda] who reigns over the earth as Creator, defeating “the rulers of the earth” (cf. Isa 40:10–42:9).

The resounding echo throughout the rest of Isaiah (esp. ch. 40–52) is that the Creator God is king; earthy kings and their idols are nothing. One of the most striking passages comes in Isa 41. God first warns Israel not to fear “for I am your God” (41:10), who is the “the Lord . . . the King of Jacob,” (41:21). After giving proof that he alone in God (41:22–24), we hear that he “shall trample on rulers as on mortar” (41:25). Finally, in Isa 41:26–27, this message being “declared” [avnaggelei/] is called “good news” [i.e. gospel; rfbm].

Jesus applies to himself Isa 61:1, which describes the actions of a victorious king: “The Spirit of the Lord GOD is upon me, because the LORD has anointed me to bring good news [rfbl; euvaggeli,sasqai, LXX] to the poor; he has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound . . . .” (cf. Isa 60:6). Thus, Isa 43:15 summarizes Isaiah’s gospel pronouncements: “‘I am the LORD, your Holy One, the Creator of Israel, your King.’”

In the New Testament, Paul preaches Isaiah’s gospel. In Acts 14:15, Paul cries out, “Men, why are you doing these things? We also are men, of like nature with you, and we bring you good news [euvaggelizo,menoi], that you should turn from these vain things to a living God, who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and all that is in them.” Acts 14:7, 21 make explicit that Paul is “preaching the gospel” [euvaggelizo,menoi] concerning the “kingdom of God” (Acts 14:22; basilei,an tou/ qeou/). Similarly, in Acts 17:24–31, his “gospel” announces the Creator “commands all people everywhere to repent, because he has fixed a day on which he will judge the world [kri,nein th.n oivkoume,nhn] in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead” (v. 30–31).[66] Finally, Paul speaks to the Thessalonians’ react to the “gospel” (1 Thess 1:5; 2:2, 4, 8): they “turned to God from idols to serve the living and true God . . . .” In short, the gospel Isaiah and Paul proclaims the one true God as king above every idol that would seek to rival him.

What has God done in Christ? A number of things could be mentioned by way of summary. He keeps his covenant promises to bless all nations. Likewise, God through Christ defeats his enemies, including demons, disease, and death. The historical events of Christ’s life, death, resurrection, and ascension are of critical importance. One must not overlook the repeated emphasis in the gospel that God has kept his promises. The “gospel [was] promised beforehand through his prophets in the holy Scriptures” (Rom 1:1–2; 1 Cor 15:3–4). Acts 13:32–34 is quite explicit,

And we bring you the good news [euvaggelizo,meqa] that what God promised [evpaggeli,an] to the fathers, this he has fulfilled to us their children by raising Jesus, as also it is written in the second Psalm, “You are my Son, today I have begotten you.” And as for the fact that he raised him from the dead, no more to return to corruption, he has spoken in this way, “I will give you the holy and sure blessings of David.”

An intriguing passage is Hebrew 4:1–6, where the Creator (v. 4) gives people “the promise of entering his rest” [v. 1; evpaggeli,aj eivselqei/n eivj th.n kata,pausin auvtou/], which is called the “good news” in v. 2 [euvhggelisme,noi] and v. 6 [euvaggelisqe,ntej]. In Gal 3:8, Paul says “the Scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel beforehand [proeuhggeli,sato] to Abraham, saying, ‘In you shall all the nations be blessed.’” Paul cites the promise made to Abraham in Gen 12:3, which shapes all of redemptive history to follow. Afterwards, this gospel is repeated referred to as “the promise” (Gal 3:14, 16–19, 21–22, 29).[67]

Perhaps the most unmistakable feature of the biblical “gospel” is Christ’s resurrection from the dead. Numerous passages have already been mentioned, such as Acts 13:30–37; Rom 1:4; 1 Cor 15; and 2 Tim 2:8. The clear message of 1 Cor 15:20–28, 54–57 is that Jesus’ resurrection marks the victory of God over sin and death. In Paul’s most concentrated treatment on the resurrection, this stands out as the defining achievement of Christ’s resurrection. Other passages that could be mentioned include Acts 5:30, 42; 10:36–40 and Rom 10:9, 14–16. A full resurrection theology will not be developed here. The emphasis on the resurrection of Christ is so pervasive throughout the New Testament, especially in the preaching of Acts, that one wonders how people could emphasize the death of Jesus at the expense of his resurrection.[68] It is the exception that Christ’s resurrection is not mentioned.

There are countless ways one could explain why gospel is significant. God saves people from the shame and condemnation of sin, which is dishonoring God by rebelling against him. Christ redeems us from slavery and adopts us as children. Other possible themes that could be discussed include glorification, re-creation, purification, and justification. Nations will be reconciled with one another.[69] Ultimately, God will create a new heaven and new earth. There will be no more sin and death since God will bring judgment upon the world’s evil, putting to shame anyone who will not respond to him in faith. There is no inherent tension between the so-called “King Jesus gospel” and a “soterion” message. Michael Bird gives a balanced summary:

But merely stating that Jesus is king is an insufficient representation of the gospel if we do not point out how he has shown his kingly power in giving himself up for our sins and being raised by God for our acquittal. The gospel is a royal announcement that God has become king in Jesus Christ and has expressed his saving sovereignty through the death and resurrection of the Son, which atones, justifies and reconciles. There is no gospel without the heralding of the king, and there is no gospel without atonement and resurrection.[70]

Since so much as been written on these various themes, I will not belabor the point here.

A number of biblical texts have already been given that demonstrate a right response to the gospel. In short, sinners turn from all idolatry to the one true God. “Repentance” refers to a changing of one’s mind or heart such that one’s sense of value, honor-shame, and identity are changed. In addition, we could talk about faith, which necessarily expresses itself in works (cf. the book of James). Faith not only means “trust” but also has the idea of loyalty. In short, we seek to convey the point that we must be united to Christ with our head, heart, and hand. People must so identify with Jesus Christ that he and his people share in one another’s honor and shame.

Towards a Cultural Contextualization

Contextualization obviously happens in context, not in abstraction. Therefore, in forthcoming articles, I plan to apply this model within Chinese context. For the moment, however, there is only room enough to explain in principle what occurs in the final part of the contextualization methodology being proposed in this article.

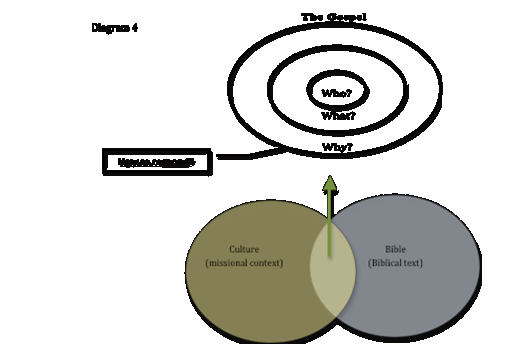

Contextualization begins in those

areas where the biblical context overlaps with the contemporary cultural

context (See Diagram 4 below).[71]

Generally, one can only talk about these parts of culture in the abstract,

perhaps making reference to terms like “collectivism,” “honor-shame,”

“patronage,” or cyclical vs. linear views of time. After all, no one today

existed in the time Scripture was written. That distance creates some degree of

abstraction, which is unavoidable. The critical point at this stage becomes

finding how to move from abstract categories to their concrete expressions in

modern life. For example, what is the “cultural language” of honor-shame in

places like France, India, and China? Each setting is going to have different

ways to express its view about what is praiseworthy, embarrassing, or

humiliating. In terms of spoken words, one does not commonly talk about “honor”

and “shame” as much as one uses words like “face” [e.g., 脸, 面子]. Actions also speak symbolically. For example,

Kipnis describes a historical Chinese context: “Ketou and bows were one

of the major components of peasant subculture. Residents who wished to

construct themselves as nonpeasants tried to avoid situations that required

bows and ketou.”[72]

The final step attempts to answer the four gospel questions by drawing from the areas of overlap between text and context. Contextualizers use whatever cultural language best conveys the ideas needing to be expressed. Negatively, the four questions provide a structure to explain the gospel as well as the various “false gospels” that plague a cultural context. The culture has functional gods and false ideologies that claim certain achievements and make promises. How are people supposed to respond to those idols in order to reap a benefit? Positively, these questions assist a person who wants to give a holistic and meaningful gospel presentation. I very briefly highlight a few relevant ways of answering.

How would one answer the question, “Who is God”? Who in Chinese culture receives people’s highest praise and loyalty? Such persons are potential idols that need to be exposed. In terms of position, they might include parents, teachers, politicians, and employers. Depending on the situation, we can affirm that God is a Father, King and the Creator. Each of these answers naturally infers a particular range of metaphors, themes, and implications. Certainly one speaks differently within a familial than in a royal framework. Various scholars have argued that the gospel, in the ancient context, would have been politically provocative.[73] One might argue that in modern China, a similar proclamation would be “Jesus is Chairman” (耶稣做主席).

What has God in Christ done? From a Chinese perspective, it is especially noteworthy that Jesus defeated death. The fear of death is so strong in China that people do not like to have phone numbers with the number four because phonetically the number four sounds like the word for death. In defeating his enemies, Jesus retakes God’s kingdom, which is occupied by human “imperialists.” Jesus overcomes shame and is honored as king by his Father. Although God’s children have made him lose face, nevertheless Jesus shows filial piety, ensuring that God will keep his promises. Accordingly, King Jesus vindicates the honor of his Father. The Creator’s name will be perpetuated throughout the human family for all generations (cf. 传宗接代).

Why does this all matter? Jesus restores harmony to our fundamental relationships. God the Father is reconciled with the human family. Those who perceive their ethnic group or nation to be at the center of human history (i.e. “middle kingdoms”) will be humbled. Those who boast in their bloodline, traditions, or social status “will be put to shame.” However, God will honor all who give their allegiance to King Jesus just as the Father has honored Christ (cf. John 17:22). As the head of the human family, Jesus endured human shame such that God’s children now have a new hope––glorification.

How are we to respond? We do not boast in self nor pursue our own face and fortune. In order to identify with Christ, we must share in the honor and shame of Jesus. It is only by forsaking other loyalties that one may come under the Father’s name. We lose face in the eyes of others so that we may see and enjoy the glory of God’s face. This implies practical obedience, which publically manifests our honor for our King. Since God’s children belong to one Father, they must commit themselves to one another, seeking to faithfully represent his name in the world. Because humanity is a family, having the same origin, we cannot have any sense of cultural superiority or nationalism.

Concluding Summary of the Contextualization Process

In order to contextualize the gospel in any culture, a few key steps are critical. First of all, one must observe the range of ways the Bible talks about the gospel, being careful to interpret each passage in its context and aware of one’s own theological biases. Accordingly, it is important to slow oneself down when reading, starting with the most explicit texts before moving to less clear verses. Throughout the Bible, gospel presentations answer fours questions. One could give multiple answers to any one of these questions. Each answer however will draw from different texts and metaphors. Not surprisingly, different passages and cultures do not lay the same stress on every possible answer. A fruitful place to begin the contextualization process is the area of overlap between the biblical text and the cultural context. One steadily moves from the abstract to the concrete. In the end, countless biblical ideas can be expressed in any cultural clothing and language.