ETHNIC

RECEPTIVITY

ETHNIC

RECEPTIVITY

AND

INTERCULTURAL MINISTRIES

ENOCH WAN

Chair, Division of Intercultural Studies and

Director, Doctor of Missiology Program,

Western Seminary, Portland, Oregon,

USA

Published in

Global Missiology, Contemporary Practices, October 2004, www.globalmissiology.net

For past decades

Canada had a leading role in sending missionaries into many countries of the

world. Then came the 1980's, and many of those countries closed their doors to outside messengers (although Brother Andrew has

maintained that there is no country you

can't get into - just ones you can't get out of). Just when we are lamenting

these hindrances, God seemed to be

opening a new door of opportunity. Canada was inviting record numbers of immigrants to join us, many from

countries which were closed to our missionaries.

We are now confronting

a new mission field, yet in some ways are unequipped for facing this challenge. Donald McGavran has given us the

necessary descriptive terms: "E-l evangelism," meaning that which

reaches our own kind of people; "E-2 evangelism," which requires crossing some kind of barrier,

usually physical, such as going into a new community; and "E-3 evangelism," which crosses cultural and

language barriers as well as physical

barriers, such as going to a new country. He says, "For E-3 evangelism,

the church must have a corps of

missionaries with special training." While we have trained our "foreign missionaries for crossing these

barriers and are putting forth a great effort, particularly in Vision 2000, to equip for E-l evangelism, what may be

lacking is help for E-2 evangelism

reaching distant.”

Most of us would

recognize that there needs to be a difference in strategy between E-l, E2, and E-3 evangelism. But as we confront the E-2

sphere of evangelism, is there anything

that can help us to better relate the gospel? When we send our missionaries to

other lands, we train them to look for ways that God has -prepared that culture

-for the gospel, ways to look for receptivity that will affect strategy. We

need to do the same, as we look at

reaching these new cultures coming to our land. In fact, our strategy for

evangelism will be deficient if this "cultural integration/variation"

is not taken into consideration. There

are factors of integration and receptivity that can help us better communicate the gospel to that culture.

In

this chapter, we will look at informative cases or situations for

contextualized evangelism of different ethnic

groups, followed by the interpretive analysis of cultural integration/variation

factors and concluded by instructive suggestions for our evangelism and

church-planting strategies within these new Canadian cultures.

Informative

Understanding of Cultural Integration/Variation:

Our

mandate is clear. The church is to evangelize the nations or the people-groups

(Mt 24:14; 28:19). Like the Christ Incarnate who in order to

reach men, became a man and lived among the Aramaic-speaking

Jews in the context of Greco-Roman culture, Christians

are to evangelize different people-groups within the context of their cultures,

which is "contextualized evangelism."

Our

mandate is clear. The church is to evangelize the nations or the people-groups

(Mt 24:14; 28:19). Like the Christ Incarnate who in order to

reach men, became a man and lived among the Aramaic-speaking

Jews in the context of Greco-Roman culture, Christians

are to evangelize different people-groups within the context of their cultures,

which is "contextualized evangelism."

The general pattern of evangelization practiced by

Anglophone Caucasian Christians needs

to be contextualized when evangelizing other ethnic groups and modified according to their various degree of cultural

integration/variation. Several simple but informative studies of contextualized

evangelism will be presented to help us understand how this can be applied to various ethnic groups.

Means of Pre-evangelism

One of the characteristics of contemporary

Canadian culture is the "impersonal informational" aspect. This may be the cumulative effects of

industrialization, urbanization,

technological revolution and information explosion, etc. consequently, the kind of pre-evangelism efforts that evangelicals

use extensively involve mass media (e.g. telephone, radio, television, printed literature and published

magazine). These are exclusively in

English, predominantly informational, and very impersonal.

The usual means of pre-evangelism by Anglophone

Caucasian Christians are inadequate and

inefficient in reaching new immigrants who are functionally illiterate in

English, relatively untouched by the

mass media, and socially isolated from the Anglophone Caucasian Christians' social network (typically of

middle-class, professional, suburban dwellers). Canadians of South Asian origin

(mostly English- speaking, relatively more westernized professionals) may be touched by the impersonal-informational

means of pre- evangelism. However,

most Canadians who came as refugees (Vietnamese, Hispanic or Arab origin) are

non-English speaking, non-professional immigrants. This group of Canadians will not be touched by the typical means

of impersonal-informational pre-evangelism by Anglophone Caucasian Christians.

Method of Contact

First

generation immigrants are culturally less integrated into the mainstream of Anglophone

Caucasians culture than their local born descendants. They usually have frequent

social interaction with their own people (i.e. extended family and kindred

spirits) in their native tongues. Newspapers, videos and movies

which are printed or produced in their native languages are the

main media of communication and the sources of information.

Being proportionately small in number, their social relationships are more personal

and intimate. Thus, pre-evangelism is best done through personal contacts and

private interaction, which better demonstrates the virtue of a Christ-like

character than extensive reliance on mass media.

Message of the Gospel

Message of the Gospel

Western culture has a Greco-Roman, politico-legal

base and Judeo-Christian ethical foundation.

The Greek social system of city-state, the Roman law, etc. has been well developed for "millennia" in the West.

The influence of the Judeo-Christian value system and moral code has

left its mark in the mind and heart of people in the context of western civilization, so much so that anthropologists who

have conducted cross-cultural comparative

studies have classified the western culture as a "guilt culture" in

contrast to the "shame

culture" of the East (e.g. Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, etc.).

The Protestant reformation had a strong emphasis

on the doctrine of “justification by faith.”

The favorite New Testament books of western evangelicals for reading and preaching are usually Romans and Galatians.

Anglophone Caucasian Christians usually define “sinners” as “people violating God’s law” and the message of

salvation is expressed in terms of

“forgiveness of sin...the penal substitution of Christ...imputed righteousness.” The gospel is introduced in the

form of “law-principle,” and in terms of “justification by faith in Christ as Saviour.”

Message in Culture

People of the East give a high priority to “honour”

and avoid “shame” at all cost. For example,

a Japanese would rather die than live in disgrace. To him wealth or health is dispensable and deniable in order to avoid shame

or acquire fame. This is in contrast to the life-long quest for success as defined by material gain of the

capitalist, entrepreneur in the West.

Easterners, such as Japanese, Koreans, Chinese, Vietnamese, Indians, can better grasp the shameful state and severed

relationship between God and man (Gen. 9:1- 11. 22), man and woman which was due to the fall (Gen. 3:16), and the

need for salvation. They will be more

willing to accept Christ as the “Blame bearer” (Gen. 3:7-8; Mk. 16:34), the mediator-reconciliator (Rom 5; 2 Cor. 5; Eph. 2; Heb. 9) for sinners who suffer because of severed relationship and the

subsequent shameful state. If the message of the gospel, presented to relational people of the “shame culture,” was

in terms of personal “reconciliation”

instead of justification (as in the farm of the “Four Spiritual Laws”), it will be better understood and more

gratefully received.

Of course, the “whole counsel of God” (Act 20:27)

should be taught eventually in a discipleship

program. But nobody should be alienated from the Kingdom of God because they are culturally unable to grasp the

overemphasized “forensic” aspect of the gospel and therefore, unprepared to accept the “penal substitution of Christ” as

presented by Anglophone Caucasian

Christians in evangelism.

Message of Power

Most

non-Caucasian Canadians from the third world take the spirit world very

seriously. The presence and power of evil forces and demonic

beings are readily recognized. Many have witnessed demonic

manifestations or even personally experienced demonic oppression

or possession. Their superstition and fear of the spirits would have prepared

them

to receive the `good news” of a mighty but merciful Christ. The classical

Christian view of Christ’s death and atonement (Col. 2; Heb.

2), setting us free from evil power, would be better appreciated than the

rational, logical argument of the existence of God. They

want to embrace Christ and experience His victory and love that could set them

free from fear and fate (1 John 3:8; 4:4,18; 5:4- 6, 18-20).

them

to receive the `good news” of a mighty but merciful Christ. The classical

Christian view of Christ’s death and atonement (Col. 2; Heb.

2), setting us free from evil power, would be better appreciated than the

rational, logical argument of the existence of God. They

want to embrace Christ and experience His victory and love that could set them

free from fear and fate (1 John 3:8; 4:4,18; 5:4- 6, 18-20).

The primary message of the gospel for these ethnic

Canadians is not a hope to enter heaven

`by and by” and deliverance from hell in the afterlife. They want to experience

the deliverance from curse, fate,

fear, etc. in the `here and now.” To these ethnic Canadians, the freedom and joy in Christ is a

liberating message and life style. It is something that can be declared clearly, demonstrated powerfully and

experienced daily.

In the context of western culture (Anglophone

Caucasians of Canada, U.S.A., and Europe),

the most popular and commonly used method of evangelism had been the well-publicized

mass rally. Ideally, it is a well-organized operation, meeting in a public

place (church building, public hall or

arena), and featuring excellent programs. People are encouraged to make a personal decision and public

profession of faith by raising their hand

or coming forward.

This has been a very effective method of

evangelism to reach Anglophone Caucasians who are relatively more

individualistic in decision-making, more public in religious expression and more program oriented in their

social gathering.

Method

of Deciding

Most ethnics of non-western origin are not

individualistic (self-directed) in their decision-making process. Whether it be Canadian Natives,

East Indian Immigrants, Chinese, et cetera,

they are more communal (family, clan-centered called `other -directed”) in

social behavior, including

decision-making. Their social gathering is usually more event, people-oriented (not program-oriented or

time-conscious). They wait till the people are there, even though it is `late” in time accord ing to Caucasian standard.

Among many ethnic groups (e.g. Japanese, Chinese,

East Indian, Africans, Hispanics, Moslems,

Sikhs), children, wives, and unmarried young adults are to submit to the authority and ruling of their parents, husbands

and the elderly males. Unlike Anglophone Caucasians, religious resolution (including acceptance of Christ as

Savior) a private family matter. The

general pattern of Anglophone Caucasians in thinking like public confession of faith, or making an instantaneous

and personal decision, needs some rethinking

before imposing it on the new converts of different ethnic origins.

Meaning

of Grace

When

evangelizing, ethnic Canadian evangelicals should modify their `felt need” approach

of outreach often used with Anglophone Caucasians. Many times we give the promise

of prosperity and problem solving, or the Gospel of health and wealth, success and

happiness. We parade the newly converted movie star, the professional athlete

or the

successful businessman in

our evangelistic rallies, and in their stage show type of program, we call for a simplistic or emotional

`acceptance of Christ.”

successful businessman in

our evangelistic rallies, and in their stage show type of program, we call for a simplistic or emotional

`acceptance of Christ.”

The problem is that it gives ethnic Canadians the

idea of `cheap grace” and of superficial showmanship to the gospel. Many ethnic Canadians from Buddhist, Hindu,

and Islam backgrounds take pride in

their religious devotion, personal discipline, and ascetic deliberation of their ancestral faith. They

despise and decline easy religious experiences as too shallow, superficial and

simplistic. In fact, many of them will have to pay a high cost for the change

of allegiance to the Lordship of Christ but would be willing to do so for the

One who paid a costly price for their salvation (Eph. 1:17; 1 Cor. 8:19-20).

An extensive period of in-depth follow-up of these

ethnic converts is necessary to deal with

problems such as family opposition, carry over superstition and syncretism,

social ostracism, lingering demonic

entanglement, et cetera. The cost of discipleship (Mt 16:24; Lk. 14:25-35), personally and socially, as part of a

well-developed evangelism program, is

not to be underestimated. The fast-food mentality and quick-fix methodology of Anglophone Caucasians should not be assumed as

valid when evangelizing ethnic Canadians

.

These factors were meant to inform as to the

importance of `contextualized evangelism” among Anglophone non-Caucasian Canadians. We now need to interpret some

of the cultural `integration/variation factors” that can help us in our

evangelism and church planting.

Interpretive

View of Cultural Integration/Variation

Canada, like the U.S.A., is an immigrant country.

All Canadians, except the Canadian Indians,

are either overseas-born immigrants or local born offspring’s. However, there

is a dominant Anglophone Caucasian

culture (or `host culture”) by virtue of its population size and duration of tradition. Although Canada is

a bilingual nation, it has a multicultural

population. There are many ethnic groups (East Indian, Chinese, Ukrainian, Italian) maintaining their subcultures in the

cultural mosaic of Canada. The trend toward racial divergence and cultural variation in Canada is a fact reflected

in the immigration policy of recent

years.

The `host culture” of Canadian Anglophone Caucasians

is a mixture of many cultures, such as British, Scottish, Irish,

American, and yet is different from the origin of each. For example, Anglophone Caucasians usually have morning

breakfast, noon lunch and evening

dinner (with snacks or coffee breaks in between) in contrast to that of the

British having morning breakfast,

noon `dinner”, afternoon `tea” and night supper. Though there be

regional variations, this is a distinctive of the `host culture” of Anglophone

Caucasian Canadians. Both the non-English speaking,

overseas-born-ethnic (`OBE”) and the local - born ethnic (`LBE”) will be

gradually integrated into this `host culture.”

There

are many factors contributing to the rate and extent of the cultural

integration of ethnic Canadians, among them are

English language skills, level of education, type of

occupation, residential

pattern, place of birth, duration of stay, etc. Detailed discussion of these

factors is beyond the scope of this chapter but two dimensions affecting

cultural integration/variation are

included in the following discussion.

occupation, residential

pattern, place of birth, duration of stay, etc. Detailed discussion of these

factors is beyond the scope of this chapter but two dimensions affecting

cultural integration/variation are

included in the following discussion.

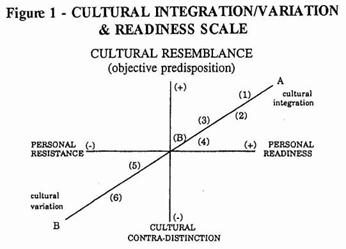

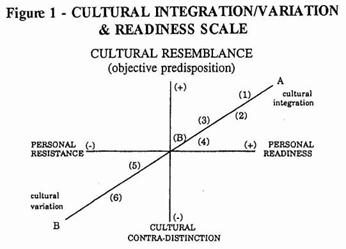

The two major dimensions in the

process of cultural integration are: objective predisposition

(`the degree of resemblance of an ODE/LBE’s own culture to the host culture”),

and the subjective preference (`an OBE/LBE’s personal choice in terms of motivation, emotion and

volition towards cultural integration). These two can also be the deterrent factors against varying degrees (in

intensity and extensiveness) of cultural integration with resultant cultural variation. (see the A---B scale in

Figure #1.)

1.

ODE Canadian from the Philippines

2.

OBE Canadian from Pakistan

3.

LBE Canadian of East Indian parents

4.

ODE Canadian from India

5.

LBE Canadian Vietnamese (Buddhist from the

countryside)

6. OBE

Canadian Vietnamese (Atheist from Bangkok) (B)

Point of “acculturation” (s ee footnote 3)

For

example, a Canadian Filipino (1 in Figure #1)

comes from a cultural background with several centuries of Spanish

colonization and decades of American domination. He, as

compared to a Moslem from Pakistan (2 in Figure

#1); can be culturally integrated into

the “host culture” easier than the latter. The cultural resemblance of (1) to

the “host culture,” contrasting to the culture contra -distinction of (2) from

the “host culture,” would make shift of (1)

to the “host culture” smoother and faster than that of (2).

On the other hand, though (3) and

(4) are both from India, the lack of personal readiness of ODE (4) will restart

the process of cultural integration as compared to LDE- (3) who has

been born and raised in Canada. The ethnic background of (S)

and (6) is Vietnamese, yet LBE- (5) has less cultural and

religious barrier to overcome than OBE- (6); the latter most

likely will prefer and remain to be more Vietnamese than the former.

This simple but basic

understanding of cultural integration and variation provides the basis of the following discussion on evangelism

and discipleship.

This simple but basic

understanding of cultural integration and variation provides the basis of the following discussion on evangelism

and discipleship.

Integration/Variation

re: Evangelism and Discipleship

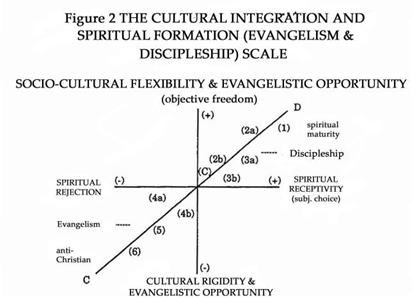

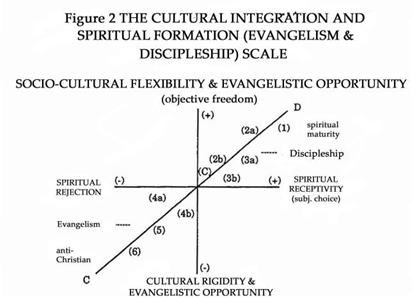

If an OBE/LBE’s cultural background is more

integrated with or similar to the “host culture,” then generally there is more opportunity for him or her to

hear the gospel and more flexibility

for that person to enjoy the freedom of accepting Christ. This leads us to a brief discussion of the two major dimensions of

both the Christian’s conversion and maturity

and the evangelization of non-Christians. (C--D of Figure

#2 is an evangelism-discipleship scale).

For example, if all things are equal, a new convert

to Christianity will grow to maturity faster

and stronger (1 in Figure #2) if he experiences favorable circumstances and has

a teachable spirit. If an individual

(6 in Figure #2)

does not objectively have the opportunity

to hear the gospel and the freedom to accept Christ, nor does he personally

show a willingness to embrace the Christian faith, he will not likely become a

Christian. In fact, he might be strongly resistant to the gospel.

The following diagram illustrates

the somewhat obvious, if both (2a) and (2b) of Figure

#2 are born-again Christians with

the same kind of teachable spirit, (2a) being from a Christian

home will be easier to disciple than (2b) being from a Moslem home. Both (3a) and

(3b) are born again Christians Catholic Filipino homes, (3a) with a teachable

spirit will mature spiritually easier and faster than (3b) who is

not receptive to spiritual things. Given that both (4a) and (4b) are

unsaved and un-churched, if (4a) has less opportunity to hear

the gospel and has to face strong opposition from Sikh parents, then he usually

will be more difficult to be evangelized than (4b). If both (S)

and (6) are non-Christian immigrants

from Singapore, the churchgoing and less resistant (S)

will more likely be reached

by the gospel than un-churched and resistant person like (6).

NOTES:

NOTES:

1. mature Christian (from Christian home, with

teachable spirit)

2a.

born-again Christian (from Christian home)

2b.

born-again Christian (from Moslem home)

3a.

born-again Christian (from Filipino home, with

teachable spirit)

3b.

born-again Christian (from Filipino home, without

teachable spirit)

4a.

unsaved, un-churched (of Sikh parents)

4b.

unsaved, un-churched (of Catholic parents)

5.

unsaved, Canadian from Singapore (churchgoing,

mildly resistant to the Gospel)

6.

unsaved, Canadian from Singapore

(un-churched, strongly resistant to the Gospel) C. point

of conversion

The cultural integration/variation and spiritual

formation (evangelism -and discipleship) scale presented above is a useful

conceptual tool for developing evangelism strategies to reach different

ethnic Canadians, evaluating evangelistic efforts among culturally diverse groups, or planning for discipleship programs for

ethnic converts. This basic understanding

of the correlation between the objective and subjective dimensions of evangelism and discipleship (in relation to the

cultural background, and personal preference

of the target group) could cultivate the cultural sensitivity of Anglophone Caucasian evangelists and disciples, calm the

anxiety of the hard-working soul winner, and encourage the disheartened Christian worker among the relatively

difficult ethnic Canadians.

Instructive

Suggestions of Cultural Integration / Variation for Church Planting

Local churches differ from one another in shape,

size, polity, language, race, etc. Of these many different factors, the

following discussion will deal with only ethnic diversity and congregational preference (in terms of cultural

integration/variation).

After

conducting successful evangelization and developing good discipleship programs among

ethnic Canadians, a church planter (or the founding ethnic members) will have

the option of forming a church that is not necessarily

homogeneous or heterogeneous but somewhere on the continuum

between the two. In other words, it may be a single-congregation

of a homogeneous group, but there are options of being a single-congregation

with subgroups making it a multi-congregation church as shown in the E---F

scale of Figure #3.

NOTES:

NOTES:

1. heterogeneous & multi-congregation church

2a.

multilingual & multicultural church

2b.

bilingual & bicultural church

3a.

monolingual & monocultural church, ethnic but

open (OBE + LBE + etc.)

3b. monolingual

& bicultural church, ethnic but conservative (OBE dominant) 4.

monolingual & heterogeneous church (only OBE or LBE)

It is natural and logical, and even expedient for

ethnic Canadians to form a monolingual and homogeneous church as in

example (4) in Figure #3. This is a common practice of OBE Canadian Christians, particularly seen in all

early Mennonite churches. The opposite

alternative is to form a multilingual, heterogeneous and multi-congregational church

(i.e., 1 in Figure

#3).

The operation of a multilingual and multicultural

church (2a of Figure #3) would usually require a lot of mutual respect, careful coordination and Christian love

to ensure the health and well being of

such a heterogeneous church. For example, many Chinese and Vietnamese churches in the province of Quebec are

multilingual using French for the local

born ethnics (LBE), as well as the mother tongue of the overseas born ethnics (OBE), and also English.

Often there

are members from several ethnic backgrounds joining Anglophone Caucasian churches in metropolitan centers. This type of

church (2b of Figure #3) is usually English speaking but multicultural. This is a version of the

“international church” found in major

cities in the world (Bangkok, Manila, Hong Kong, Mexico, etc.).

Ethnic churches may begin with a

monolingual immigrant congregation made up of OBEs. Later, when the new

generation(s) of LBE or new converts from other ethnic backgrounds increase in

number, the church may remain monolingual (of the mother tongue of OBE) yet become multicultural (3a of Figure

#3).

The

more conservative ethnic church dominated by OBE (without integrating other ethnic

Canadians or accommodating the LEE) may remain monolingual (mother tongue of OBE) but bicultural

(3b) of Figure #3.

The

more conservative ethnic church dominated by OBE (without integrating other ethnic

Canadians or accommodating the LEE) may remain monolingual (mother tongue of OBE) but bicultural

(3b) of Figure #3.

In a pluralistic and multicultural society like

Canada (and the U.S.A. in contrast. for example, to many Moslem countries), the E-F scale is a continuum of

heterogeneity and homogeneity with

many options for church planting. This is a good and healthy model especially when the population of Canada and the

United States is changing towards greater

racial diversity and cultural plurality.

Conclusion

Cultural integration/variation is an interesting

and important aspect of Canadian life. Those

who are committed to evangelism and church planting in Canada must take into consideration the multi-ethnic, multi-cultural

trend of the population. The vision of the lostness of man and the mission of nationwide and worldwide

evangelization require new efforts

and cooperation on the part of Canadian Christians (Anglophone Caucasians, overseas-born ethnics and local-born ethnics alike)

to share the gospel with the unsaved and

un-churched, whatever their race may be. And as we are willing to be His

witnesses, He has promised the power

of the Holy Spirit, not only in our Jerusalem (E-l) or just to the far corners of the earth (E-3), but also in

our `E -2 evangelism” -- our Canadian

`Judea and Samaria.”

Editor’s Note: Used by

permission from China Alliance Press. Originally published as chapter 14 of a compendium volume, Missions Within Reach:

Intercultural Ministries in Canada, edited by Enoch Wan, China Alliance Press: Hong Kong, 1993.

![]() ETHNIC

RECEPTIVITY

ETHNIC

RECEPTIVITY