Understanding and Teaching

Religious Belief Systems

in the 21st Century Missions

by Norman E. Allison

(Former President – Evangelical Missiological Society)

Published on Global Missiology, October, 2006, Featured

Article

Introduction and Background

My purpose in writing this paper

is to demonstrate the use of a systems model as a way

to enable both graduate and undergraduate students who are training for

cross-cultural ministry to use specific models

to examine the structural properties of religious belief systems. In

so doing I am trusting that some who read or hear this presentation will see this

subject as a valuable area of preparation that should be taught more widely in undergraduate

and graduate studies for prospective or current cross-cultural workers.

Through

the application of logical models to case studies, students are trained to understand how religious beliefs are structured

in the minds of people and how they express themselves in the daily lives and rituals of people in every part of

the world. The ultimate purpose of the course

is to train cross-cultural workers to be able to understand and to empathize more deeply with the people among whom

they will serve.

As

we teach this course at Toccoa Falls College (undergraduate), Cultural

Anthropology is the minimum prerequisite. Students have been

trained in this and prior courses

(Applied Anthropology, Peoples of the World, Ethnography, World Religions,

etc.) to recognize the worldviews of

other people. In the course, Religious Belief Systems [RBSJ, we work to deepen this approach so that students

begin to see how to view the people of a second culture in such a way that they see the world through the

eyes of those with whom they share

the Good News, and they begin to understand the world as they do,

i.e., to think as they think.

Many theologians are concerned

that in any use of anthropological theory there is always

the danger of adopting a purely relativistic approach to the study of the

beliefs of a people. They are correct in being concerned...as

they should be for their own discipline as well;

however, from an evangelical Christian perspective, the overriding concern for

the undergirding application of biblical absolutes to

theoretical models should prevent this. In recent

years there has been concern expressed that missiologists have gone too far in

the application of anthropology to missiological issues. I do

not join in that concern. In fact, I

2

am more

concerned that many Christian workers, even cross-cultural workers, have little

or no interest or training in anthropology.

Whatever our training may

include, none of us can take our

assumptions for granted without

ongoing evaluation. Christian anthropologists,

must always apply biblical absolutes

in such a way that they will form the essential guidelines for any application

of theory. In the Religious Belief Systems course, students know, from the first few days of class, the explicit biblical

assumptions which will guide our study, and they are cautioned to question any movement away from those guidelines.

From another

direction, contemporary discussions in anthropological literature have expressed continuing concern with the imposition

of Western structures of understanding on

non-Western cultural data. In this course I work to see that emic1

structures are given a high priority,

and I encourage the primarily monocultural students to examine non-Western beliefs and values without the inherent

ethnocentrism so often seen in the history of their predecessors. In our discussions, I often ask

questions to see if their perception is being modified to consider non-Western alternatives in solutions to problems

in case studies. It is gratifying to

see, as the semester progresses, that there is movement away from monocultural assumptions and reactions.

The

history of anthropology is replete with numerous theories designed to help us understand the mosaic of peoples and their

cultures around the world. They tend to come and go with time. As for my own approach in dealing with the

complexities involved in communicating

the Gospel in other cultures, exposure to various alternatives has led me to adopt a mixture of theoretical approaches.

Although my perspective and my methodology may be seen as eclectic, I follow what is known as the general

systems theory2 approach to cultural analysis, modified by a functionalist3

mentality, a bit of symbolic and cognitive theory, and a few other strange ideas...all further molded by my

evangelical Christian worldview! So

if my approach may be a little difficult to classify at times, this is the reason!

It

may be worth mentioning here that in recent years, many anthropologists seem to

be moving away from understanding

the intricacies of culture through the study of structural systems. In fact, in our postmodern world, all theories,

definitions, and methodologies seem to be open to new interpretations. In an

article just published in the

3 monthly

news publication of the American Anthropological Association, under the

subtitle, Postmodern Suspicion of Structure, one

professor writes:

“...in anthropology, we see a

move away from the panoramic sweep of cultural systems,

whether of a positivist stripe or hermeneutic grandeur.

...the trend in anthropology is

away from cross-cultural comparison and a search for statistical

or other universals. How ironic that, as the forces (and structures) of globalization

increase, anthropology turns more toward local knowledge and practice

” (Maynard 2003:8 &11).

So,

as some behavioral scientists in this postmodern era move to change how they

and we should understand the societies of the world, there is still a strong

affinity among some of us for the use

of the “systems” approach in the study of religion and related beliefs and practices. The data in this paper follow that

approach.

In addition to the influences I have noted, my thinking

has also been challenged and shaped by the writings of

Christian anthropologists Alan Tippett, Paul Hiebert and Charles Kraft,

along with missiologist, David Hesselgrave and others. In fact, some of their

ideas are so mixed with mine,

I have difficulty in sorting

them all out as I teach this course and write this paper! But I will

attempt to give credit where I am aware of using source materials...at least

they will all be mentioned in the attached bibliography!

In

the specific application and integration of all these factors, I need to

further state that my own study of religious

belief systems began during the ten years I spent working among the Arabs of Jordan and Lebanon. One of the many

things I learned as I lived among

these gracious people was how little I knew about the way they thought

and how little I understood the

worldview that guided their lives.

Later,

when I knew I was going to stay in the USA to teach, the Lord

opened the way for me to study cultural anthropology at the University of Georgia. There, I was able to take a concentration in Belief Systems.

Among many scholars introduced to me by Dr. Charles Hudson, my major professor in this concentration,

was a writer by the name of Robin

Horton, professor of Philosophy and Religious Studies at the University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. My first exposure to

his writings was through a book titled,

Rationality (1970), edited by Bryan Wilson. In that volume, Horton

examined the similarities underlying

African thought and Western science, and then compared

4

differences.

More recently, he has expanded his work in his own book, Patterns of Thought

in Africa

and the West: Essays on Magic, Religion, and Science

(1993).

The Course

My

design for this course: Religious Belief Systems ("RBS" to students),

gives a background in theory and

then uses a simple beginning model developed for the study of religious beliefs in any culture. I have kept

this model simple because I want it to be useful to undergraduate students,

most of whom have limited experience in dealing with other cultures. It is also

easy to remember and apply in whatever cultural system they work with.

I should mention,

also, that what I am writing does not give an overview of the whole

course, but does give what I believe to be the core of what I am

teaching in that area. Later I will

list topics covered during the entire semester and this will indicate the

broader scope of the subject.

I emphasize in class

that when we deal with the subject of Religious Belief Systems, we are really dealing with the way people think.

We are not just examining beliefs and values,

even though that is an important part of our study. Our focus is on how these

are structured in the human

mind.4 I have worked

to simplify many of the intricacies related to the subject in order to focus on a way of communicating with

undergraduate students which will interest and enlighten them, and to give them

tools which may be developed further

as they work with the complex beliefs of societies around the world. Some of

them may question whether I have

been successful in this goal, but most of them do seem to express a high level of interest.

Early in the course

they read Paul Hiebert’s classic article, “The Flaw of the Excluded Middle.” (1982:35-47) and we discuss this in class.

Students begin to see, many for the

first time, that our Western two-tiered view of the

universe typically leaves out an entire

dimension in the worldview of people in non-Western cultures. The model given

by Hiebert in the original article

is titled “A Western Two-Tiered View ofReality.”

For

those of you who may not be familiar with this concept, the Evangelical

Dictionary of World Missions

describes it this way:

For

those of you who may not be familiar with this concept, the Evangelical

Dictionary of World Missions

describes it this way:

Hiebert

built his analysis on a two-dimensional matrix. The first

dimension is that of three

worlds or domains: 1) a seen world (that which is of this world and seen), 2) the unseen of this world

(that which is of this world but not seen), and 3) an unseen transempirical world (that which pertains to

heavens, hells, and other worlds).

The second dimension is that of two types of analogies people use to explain the powers around them: 1) an organic

analogy (powers are personal, e.g., gods and spirits) and 2) a mechanical

analogy (powers are impersonal, e.g., gravity and electricity).

Combining the seen/unseen/transempirical worlds and organic/mechanical analogies into a matrix, Hiebert's model highlighted

the difference between Westerners,

who tend to see only two worlds (the seen world and the transempirical world) and many non-Westerners

who recognize the middle world, comprised

of unseen powers (magical forces, evil eye, mana) and spirits which are very much a part of everyday human life (e.g., a

person is ill because of a curse or a spirit

attack). The blind spot in the Western worldview Hiebert labeled the flaw of the excluded middle (2000:363).

With conceptual models like this,

the students begin to realize that it is important to understand

that people in different societies actually do see the world around them very differently.

They also begin to comment that the work God has called them to do is a bit

more demanding than they had thought previously.

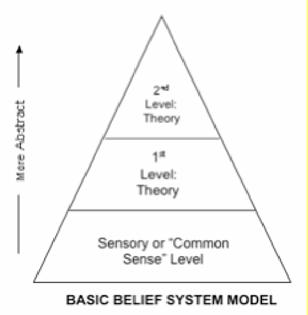

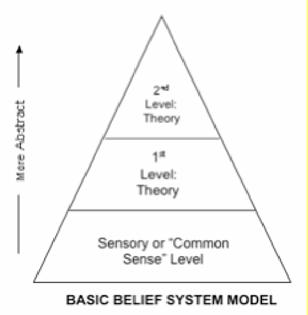

From this point, I introduce a very simple model based on

a three-level triangle which looks at the process of human thought as it moves

from sensory perception at the base through levels of

abstraction. The model is simple because I want to reiterate to

6

students that no matter how

complex the religious belief system they study may be, there will nearly always be two consistent themes. The

model looks like this:

FIG. 2

This model shows the students

that

1.

human

thought processes tend to move from the level of

“sensory perception” at the base to a more “abstract” category and then on to

higher levels of abstraction (more than two, but this keeps the

model simple).

2.

more

and more is explained by less and less as

one moves toward the more abstract upper point of the triangle.

As

I re-introduce these very fundamental concepts periodically, the students are

able to use this model as a basic

building block throughout the course.

Quite often in cultural

anthropology, we stress differences between people in different cultures

because monocultural people are prone to assume that other people are just

like they are, with a few variations.

This is one of the major reasons for using ”The

Flaw of the Excluded Middle”(Hiebert 1982:35-47) early in the course. This

often profoundly modifies student thinking about worldviews. In

addition, as different belief systems are studied, students

are presented with a number of case studies illustrating an unlimited

number of different ways people devise to organize their religious

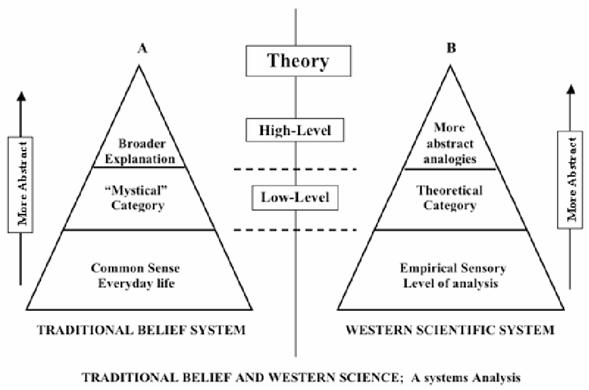

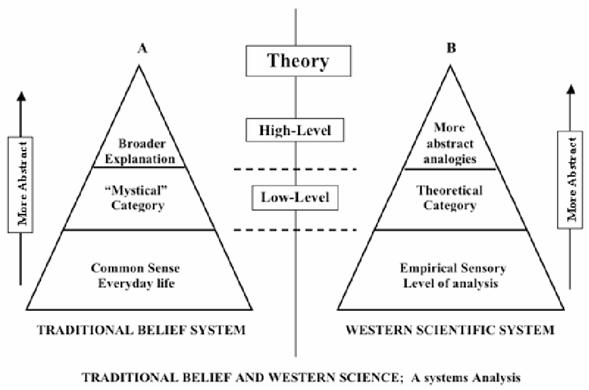

beliefs. However, at a certain point in the course, similarities between Traditional

(or Folk, or

7

Primal)

beliefs and those of people who have been taught in a Western scientific

context need to be stressed as well. So I move on to a

variation of this model to make comparisons:

FIG.3

Then, as I help students think

through the implications of this model, I refer to the following

premises5:

1. The theoretical character of

thought in traditional belief systems is essentially the

same as that in Western scientific thinking. In

other words, “Common sense” in both systems

of thought (traditional and Western) is the simplest tool for dealing with circumstances

in everyday life. However, when problems are not solved with common

sense solutions, both systems allow for thinking to move into a “higher,” more

abstract level.

Model A, the Traditional Belief

System: Let me illustrate this with an example from Robin

Horton’s work among the Kalabari people of Africa. He

describes how these people have a variety of herbal

treatments for diseases. Several of these may be tried in order to bring

about recovery. If no result is produced, they begin to say, “there is something else in

this sickness.” In other words, when the

level of common sense is too limited, the diviner is

called and the search moves into the “mystical category” to find the

cause. This

8

category is

familiar to the Kalabari...they do have a “middle” level...so they think and interact

with the spirit world on a daily basis. The diviner often looks for a possible

causal relationship between the social lives of the individuals

[anger, envy, etc.]. His worldview is very holistic and it is his

responsibility to determine the cause of an illness or misfortune and

usually to prescribe the cure, so his solution is a move into the middle level.

So

what has been described here is a “jump,” in the minds of the diviner and the people involved, from common sense to “mystical

thinking” in the traditional or folk belief system. For this type of belief system, most answers are found in the “common

sense everyday thought modes,” but if solutions to problems are not found there,

it is not uncommon to make this jump.

Since the “mystical category” is so holistically entwined with the “common sense” level in

traditional systems, the transition to this level is normally not a difficult one to make.

Model

B, the Western scientific system:

Using Horton’s illustration to show similarity

between the two modes of thought, a physicist is pictured looking intently through his microscope. He is observing small,

fast-moving particles going through a sheet of metal foil in his laboratory experiment. These particles are too

small to analyze, so he needs to compare them with some known quantity. As he

observes, he sees that these puzzling

observations have a similarity to the movements of planets in a solar system.

In his thinking, he has shifted from

the observable but unknown, to an analogy made with a known quantity. He has, in fact, moved into the

first level of abstract theory to find an answer to his problem. There are differences between the two systems,

but the similarities in arriving at

solutions are basically the same.

2. The level of abstract theory

(high/low) used varies with the context.

An interesting aspect of this premise is that a

person’s choices, as he moves into the abstract

levels of theory, will depend on how wide of a context he wants to consider. If

he believes it necessary to use only

a limited area of experience (beyond that of “common sense”), he may use what

is generally called a “low-level theory.” Of course, this is not the only factor (limitations based on intelligence,

range of experience, etc. are important), but

this is

how solutions are normally arrived at. If he has deeper concerns, he may use a

higher-level of theory.

Since our class is concerned

primarily with understanding non-Western belief systems, this understanding is

further illustrated through readings from Nuer Religion, by E. E. Evans‑

9

Pritchard. In

one of the interesting references to his work, we discuss his premise that, “A

theistic religion need be neither monotheistic nor

polytheistic. It may be both. It is the question of the level...of thought, rather than

of exclusive types of thought” (1956:316). If you

understand monotheism to be exclusive in a system of belief, this may sound

like a contradiction in terms. However, in a number of belief

systems, like that of the Nuer, one “high” god and many spirits can

and do play complementary roles. The “level of thought” referred

to by Evans-Pritchard would equate in our model to a “monotheistic god” at the “high”

level, and a “polytheistic” realm of spirits at the “low level” of theory

(which compares to the middle range of Hiebert’s model which is

excluded by Westerners).

In traditional belief systems, spirits

provide explanations in broad but clearly defined contexts. This vital worldview belief relates

primarily to one’s immediate community and environment, and to daily concerns. A supreme being, however, while

related to a higher-level of theory,

tends to provide a means of explanation which relates to theories of the origin

of life, the reason for existence,

etc.

An interesting validation of the triangle-shaped

model is that more and more is explained by less and less as one moves up toward the

peak of the triangle. The “mystical” or “1st level of theory” explains a broad range of issues which confront

people on the daily sensory level.

The “2nd level of theory” provides an even broader

explanation as thought is generalized

into fewer abstract categories.

Another illustration of the use of “high/low

levels of theory” varying with context is when, in non-Western systems, a sickness does not respond to herbal

treatments of various kinds. The

practitioner may re-diagnose and try another alternative, but if there is still

no result, the conclusion is that

there is something else in this sickness. In other words, the context provided by common sense is too limited

and there is a shift to “mystical thinking” to resolve the problem. The Western analogy might be

the use of prescription medications to cure

an illness, but if this has no benefit, one may shift to prayer to resolve the

problem.

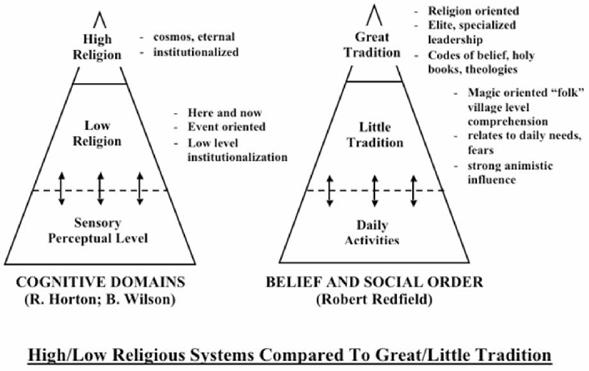

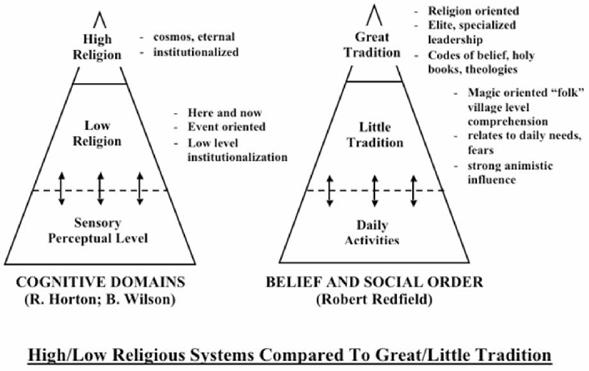

Later in the course, another topic, closely related to

the understanding that has just been developed, deals with the

comparison of “high” and “low religion,” to “Great” and “Little

Tradition.” I

generally use this model to explain the relationships:

10

FIG. 4

“High Religion” has been defined as “a

cognitive domain that is expressed in a highly institutionalized social organization”(Wilson 1970). We see this

in Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism,

Islam, etc. The characteristics of this domain of “high religion” are:

1. It deals primarily

with cosmic questions such as the origin and destiny of things, and the ultimate meaning of life.

2. It has written

texts that solidify or “fix” an authoritative body of beliefs. Since these texts are then unchangeable, as time passes,

commentaries must be written to make these meaningful and applicable to new times and changing cultures.

3. It is institutionalized.

This means a High Religion is characterized by specialization with different leadership and religious roles; it

has formally defined orthodox positions; it has central institutions such as temples or churches and schools for

training leaders, and it has bureaucratic

organizations of many forms.

4.

For the most part, “high

religion” provides for moral systems in which the gods (usually

male dominant) are good and in conflict with demons or “devils” who are evil.

By contrast, the category of “low religion” is a

cognitive domain in religion that is less institutionalized, and

centered more in immediate people-oriented needs and practices. Low

religion tends to have the following characteristics:

11

1.

It deals with the immediate problems of

everyday life... not ultimate matters. It is concerned with crisis,

disease, death, drought, etc.

2.

It is often “informally” organized. The

leaders may not even be specialists but only perform their religious services incidentally to their everyday work.

3.

It has no written texts. Beliefs are found

in myths, dramas and religious performances,

and since these are not “frozen” by being put into an unchanging form, they can change over time without the people being aware of it. So this

means they can be reinterpreted for

each new problem or occasion.

4.

A Low Religion is often amoral.

Emically, the spirits and beings in this world are understood

as being good or bad (more analogous to people). They help those who serve them

and harm those who forget them.

Somewhat

parallel to the model from R. Horton and B. Wilson is that of Robert Redfield.

Redfield was a professor at the University of Chicago and

did his field work in Mexico. He

studied concepts of folk society and folk culture, and attempted a closer integration

of the social sciences and the humanities. He classified a framework for categories

or domains of religion as ”Great” and ”Little

Tradition” (1973). Redfield

has taken a little different direction in relating

belief to social order, but it works itself out in

essentially the same way. If we focus with Redfield on the cognitive domain of High

Religion, especially in the context of

their social institutionalization, several levels of organization

can be discerned.

The Great Tradition refers

to great centers of organized religion, its central cathedrals, mosques, etc.,

training centers, formal bureaucracies, holy writings, and organizational

structures. It is here that we find the highest arenas for religious activity. Here

you have the clergy, the theologians, the leaders, and the scriptures of the

religion.

It is also important to know

that most of the books written about the world’s major religions deal

with the Great Tradition, giving extensive information about how it is rationalized,

delineating its systematic codes of beliefs, its commentaries, its

organization, etc. Most students who plan to work in second

cultures are directed to these kinds of sources.

They are, of course, important to give the ideal perspective of the

religion in question, but they give only a partial picture of the true nature

of actual belief.

The Little Tradition refers to the actual

expressions of the Great Tradition worked out in the daily lives of people at the “folk” level.

This is the religion of the average

12

believer...often

in the lives of people at the rural, peasant, or small village. A significant high level of the

population of most societies around the world function at

this level. Here there is a great deal of variance in the content, and even in

the structure of belief systems of the people, although the primary contrast is

between the Great and Little Tradition. Little Tradition

beliefs correlate poorly with what is defined as orthodox by the Great

Tradition. The Great Tradition tries

to control the lower levels, and determine for them what is orthodox

and correct, but in most areas of the non-Western world this is difficult. The

“fit” is better if channels of communication between the top

and the bottom are good, but this is most often not the case.

Redfield

also notes that ideas most often spread horizontally through the “folk” channels of communication across the Little

Tradition. They may also move up from the Little Tradition and find

acceptance in the Great Tradition, or they may be passed down from the Great to the Little Tradition.

Change is introduced in a number of ways, but it is usually very slow compared to changes in the

Western world. In addition, Redfield adds that the leaders at the level of Great Tradition may be unaware

of variations at Little Tradition level.

In teaching the course, I draw these and other concepts together, and consistently refer back

to The Excluded Middle in Western cognitive orientation. This middle

realm of belief, as we have seen, is important

and even vital to the belief systems of non-Western peoples, structurally and

practically. If we neglect it or disregard it, we will have potentially serious

problems in communicating the Gospel to people in other cultures. Having been

trained in Western education modes of thought, our automatic

reaction is to exclude this middle level and look for answers in other

categories of thought.

Historically,

and even today, when many cross-cultural workers enter a new society, many are not aware of the kinds of differences

that people make in categorizing religious beliefs. The workers focus on learning the language and proclaiming the

Gospel and generally assume God will

take care of the rest. An understanding of Religious Belief Systems is a tool in the process of contextualizing the Gospel in a new

society; but, it is a crucial tool. For example, there are some typical

mistakes to be seen as inferences are drawn from these various models:

1. Most Western-trained

missionaries and preachers, both having a Western cognitive

orientation centered in the “High Religion” realm, tend to concentrate

almost

13

entirely on issues of “High

Religion” which they believe are essential to bring about changes in the lives of people to whom they take

the Gospel. This is especially true if they have no training in cultural anthropology. Because "high

religion" is the central area of concern in their lives, and

because they are specialists in areas dealing with a high content of

theory, they unconsciously expect that to be the focal point to be dealt with

in the lives of others. Often, their communication is framed in “high

religion” sorts of concepts...primarily in

theological language, a major component of their own education. Even thought this may be “simplified” by those

working in a second culture, at least by their standards, it often seems

irrelevant to the daily lives and needs of average people.

2.

Western-oriented people often do not notice the Low Religion of a

particular area, or if they do, they

usually discount its importance. In the scientifically-trained worldview of the Western missionary, hearing that

sickness is caused by witchcraft or evil spirits seems like superstitious nonsense. He knows that germs cause

sickness. Even though he knows the

Bible teaches the interrelationship of the seen and unseen world of spirits, and though intellectually he believes

the Bible, he is conditioned in his automatic responses to such phenomena by his own scientific

training. He mentally takes the supernatural of low religion and puts it into the natural

category of his own Western belief system,

or excludes it entirely as “superstition.” Of course this is mainly due to the “excluded middle” in the Western worldview and

the failure to understand the importance of that entire area in the lives of non-Westerners which is so

important to them.

Obviously the form of

Christianity that comes to non-Western peoples often

fails to answer the questions raised in their daily lives. These questions were

answered by their old low

religion. For this reason, new converts usually turn back to the old religion to meet these needs. Or they may

take some religious symbol from the new religion, like the cross, and treat it like the old low religion symbols

are used (e.g., as magical).

There are some uncomplicated

solutions to these problems; however, they have profound

implications. It must be emphasized that:

1.

Cross-cultural workers must communicate in the forms of Christianity

that speak to these immediate, daily

real needs. It is usually much more appealing to people in “traditional” or “folk” cultures to relate the Gospel to points of need they

feel now, than to begin with the

cosmological issues of belief found in the “High Religion” domain of

14 Christianity. The

Bible does speak to those felt (and deeper true) needs, and those

biblical

solutions

must be studied, learned in an emic context, and applied in new

cultures.

2. Cross-cultural workers must

discover the cognitive domains of explanation in particular

societies and speak to all of those domains. If they only work with one area, viz.,

the “High Religion,” people will be only “partially converted.”

Many, if not most, “Christians” in the non-Western

world seem to be “High Religion” converts, but functioning

“folk religionists.” Lack of understanding on the part of Western cross-cultural

communicators of the intricacies of other belief systems may be at least

partially responsible for this very large and continuing

problem among people who claim to be Christians in every society

around the world.

What I have described thus far deals with issues that are

at the core of this course, but, as I noted at the beginning

of this paper, there is much more. The topics we cover in class, and through assigned readings

are:

(1)

History of the Anthropological Study of Religious

Belief Systems

(2)

Animism-The

Starting Point

(3)

The Flaw of the Excluded Middle

(4)

Western Beliefs vs. Traditional

(5)

Witchcraft, Sorcery and Magic

(6)

Religious/Magical Practitioners

(7)

Nuer Religion

(8)

Worldviews & Kinship-Based Cultures

(9)

Sins:

Cultural or Theological

(10) Symbolism and Ritual

(11) Power Concepts

(12) Spirit Possession

(13) Power Encounter

(14) Kalabari Worldview

(15) High and Low Religion

(16) Cognitive Categories

& Conversion

I also use several videos to

give a visual representation of what is primarily theoretical to these

students who have a limited cross-cultural experience.

The course papers done by

students in this class have given some surprising results of what

they have learned and applied in the course, many of them in ways that take the

application of this knowledge beyond what they are

expected to grasp in this undergraduate class.

As the course progresses, students are given more complex case studies and demonstrate

models of those belief systems, adding more content to the simple model with which

we begin. They are encouraged to think through the intricacies of the specific

system

15

they are studying and to diagram and analyze the belief

system as carefully as they can. Their final

course paper must include the model they construct and explain the rationale

for the way elements are placed in the

model.

My objective today is to give you a taste

of what we teach at Toccoa Falls College in the School of World Missions, specifically in the

analysis of religious belief systems. As I noted earlier, one of the major reasons I teach

this course is to emphasize how and why students should do more in-depth study as to how people of other

cultures think.

Listening to a former student of mine, now a

missionary, speaking of his work among the

Fulani in Guinea, I was interested to

hear how he had applied some of the principles learned in class. He and his wife have worked there fifteen years. He

emphasized that two factors were

important in reaching the Fulani. First, relationships had to be established. “People,” he said, “must know you before they will believe what you have to

say. And you have to demonstrate

that you believe what you say.” Then

he added, “Western people tend to start with the roof...but with the Fulani, we have to build a

foundation first.”6 I

took this as a confirmation that he

had applied lessons he had learned in the School of World Missions at Toccoa Falls College.

I believe that as students of Religious Belief

Systems communicate the Gospel in other cultural frames of reference, they will be able to better understand

systems of thought and belief as they

work within the worldviews of the people they have gone to serve. I trust that you will consider the benefits of such training

for all students in ministry, especially those planning to be cross-cultural

workers.

**********

1Any

analysis should be done on the basis of and understanding of culture from the

inside. This insider’s viewpoint is known as an emic perspective.

The perspective of the informed outsider is called an etic perspective.

The terms were developed by linguist, Kenneth Pike, for

many years associated with the Wycliffe Bible Translators, and are now widely

used by anthropologists.

2General

systems theory grew out of the work of Austrian biologist Ludwig von

Bertalanffy (1901-1972). It encouraged anthropologists to

examine cultures as systems composed of both

human and non-human elements. It presumed that the normal state of a system was

equilibrium and described the various methods by which systems deviated from

states of balance and were returned to them. Roy A. Rappaport (1926-1997) was a

major proponent (cf. “Ritual Regulation of

Environmental Relations Among a New Guinea People”).

Other

16

background is

given in Understanding Folk Religion, P. Hiebert, R.D. Shaw, and T. Tienou,

chapter 2.

3Here I am referring to what is known as the

“psychological functionalism” of Bronislaw Malinowski. Briefly stated, the theory is that cultural institutions

function to meet the basic physical

and psychological needs of people in a society.

4A sub-category of cultural anthropology known as

“Cognitive Anthropology” has helped to

formulate some of my thinking, however a weakness of

this model, which I believe to be very

important, is its lack of emphasis on the use of historical contexts in this

type of analysis.

5The following statements are drawn largely from African

Traditional Thought and Western

Science, by Robin Horton, in Rationality,

Bryan R. Wilson, ed. and from Patterns of Thought in Africa and the West, by Robin Horton (See bibliography for full

references). 6From Kenneth Blackwell, speaking at the First Alliance Church, Toccoa , Georgia, February, 2003.

17

BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS:

Awolawu, J. Omasade

1979 YORUBA BELIEFS AND

SACRIFICIAL RITES. London:

Longman

Group.

Bacon, Betty

1979 SPIRITISM IN BRAZIL. London: Latin American Group

of

EMA.

Bastide, Roger

1978 THE AFRICAN RELIGIONS OF BRAZIL. Trans. Helen

Sebba. Baltimore: John Hopkins University

Press.

Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann

1966 THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF REALITY: A TREATISE

IN THE

SOCIOLOGY

OF KNOWLEDGE. Garden City: Doubleday and

Company.

Bloomfield, Frena

1983 THE BOOK OF CHINESES BELIEFS. London: Arrow Books.

Bong Rin Ro

1985 CHRISTIAN

ALTERNATIVES TO ANCESTOR PRACTICES.

Taichung, Taiwan:

Asian Theological Association.

Burnett, David

1988 UNEARTHLY POWERS: A CHRISTIAN PERSPECTIVE ON PRIMAL AND FOLK

RELIGION. Nashville:

Thomas Nelson Publishers.

Davis, Wade

1985 THE SERPENT AND THE RAINBOW. New York: Warner

Books.

Douglas, Mary

1973 RULES AND

MEANINGS. Penguin Books.

1966 PURITY AND DANGER: AN ANALYSIS

OF THE CONCEPTS

OF POLLUTION AND TABOO. London:

Routledge and Kegan

Paul.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E.

1956 NUER RELIGION. New York: Oxford University Press.

1965 THEORIES OF

PRIMITIVE RELIGION. New York: Oxford U.

Press.

1976 WITCHCRAFT, ORACLES AND MAGIC AMONG THE

AZANDE. Oxford University Press.

Fortes, M. and G. Dieterien

1965 AFRICAN SYSTEMS

OF THOUGHT. London: Oxford

University Press.

Frazer, James G.

1922 THE GOLDEN BOUGH. London: MacMillan Press Ltd.

Geertz, Clifford

1967 ISLAM OBSERVED: Religious Developments in Morocco and

Indonesia. New

Haven: Yale University

Press.

1969 THE RELIGION OF JAVA. New York: The Free Press.

van Gennep, Arnold

18

1977

THE RITES OF PASSAGE. London:

Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Harwood, Alan

1970 WITCHCRAFT, SORCERY, AND SOCIAL CATEGORIES

AMONG THE SAFWA. London: Oxford U. Press for the

International African Institute.

Hicks, David

1976 TETUM GHOSTS AND KIN. Los Angeles: Mayfield

Publishing.

Hiebert,

Paul

1976 CULTURAL

ANTHROPOLOGY. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

1985 ANTHROPOLOGICAL

INSIGHTS FOR MISSIONARIES.

Grand

Rapids: Baker.

1993 Evangelism, church and

kingdom. In THE GOOD

NEWS OF THE KINGDOM.

Charles Van Engen, Dean S. Gillaland, and Paul Pierson, eds. Maryknoll, NY:

Orbis Books. 151-61.

1994 ANTHROPOLOGICAL REFLECTIONS

ON MISSIOLOGICAL ISSUES. Grand

Rapids: Baker Books.

1999 THE MISSIOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS OF EPISTEMOLOGICAL SHIFTS.

Harrisburg, PA:

Trinity Press.

Hiebert,

Paul, R. Daniel Shaw, and Tite Tienou

1999 UNDERSTANDING

FOLK RELIGION. Grand Rapids: Baker

Books.

Horton, Robin

1993 PATTERNS OF THOUGHT IN AFRICAN AND THE WEST:

Essays on Magic, Religion, and Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kiev, Ari

1974 MAGIC, FAITH, AND

HEALING. New York: Free Press.

Kluckhohn,

Clyde

1967 NAVAJO

WITCHCRAFT. Boston: Beacon Press.

Kraft,

Charles H.

1981 CHRISTIANITY IN CULTURE: A STUDY IN DYNAMIC

BIBLICAL THEOLOGIZING IN CROSS-CULTURAL

PERSPECTIVE. Maryknoll, NY:

Orbis Books.

1989 CHRISTIANITY WITH POWER. Ann

Arbor, MI:

Servant Publications. 1996

ANTHROPOLOGY FOR CHRISTIAN WITNESS.

Maryknoll,

NY: Orbis Books.

2001 CULTURE,

COMMUNICATION AND

CHRISTIANITY.

Pasadena: William Carey

Library.

Kraft, Marguerite G.

1995 UNDERSTANDING

SPIRITUAL POWER. Maryknoll, NY:

Orbis Books. Levi-Strauss,

Claude

1963 TOTEMISM. Boston: Beacon Press.

1979 MYTH AND

MEANING. New York: Schocken Books.

Loewen,

Jacob A.

2000 THE BIBLE IN CORSS-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE.

Pasadena: William Carey

Library.

19

Luria, A.R.

1976 COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT: ITS CULTURAL AND

SOCIAL FOUNDATIONS. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Luzbetak, Louis

1963

THE CHURCH AND

CULTURES. Techny, IL:

Divine Word

Publications. Reprinted, Pasadena: Wm. Carey Library, 1978.

Malinowski, Bronislaw C.

1954 MAGIC, SCIENCE, AND RELIGION.

Garden City, NY:

Doubleday.

[Original 1925]

Mayers, Marvin

1974 CHRISTIANITY CONFRONTS CULTURE. Grand

Rapids: Eerdmans. Middleton,

John (ed.)

1967 GODS AND RITUALS. Austin: University of Texas

Press.

1967 MAGIC, WITCHCRAFT, AND CURING. Austin:

University of

Texas.

1967 MYTH AND COSMOS. Austin: University of

Texas

Press.

Musk, Bill A.

1984 POPULAR ISLAM: AN INVESTIGATION INTO

THE

PHENOMENOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGICAL BASES OF POPULAR

ISLAMIC BELIEF AND PRACTICE. Pretoria: U. of South

Africa.

1995 TOUCHING THE SOUL OF ISLAM: SHARING THE GOSPEL IN MUSLIM

CULTURES. Crowborough: MARC.

McGee, R. Jon, and Richard L. Warms

2000

ANTHROPOLOGICAL THEORY: AN INTRODUCTION AND HISTORY.

Mountain View, CA:

Mayfield Publishing Co. Moreau, A. Scott (Ed.)

2000 EVANGELICAL DICTIONARY OF

WORLD MISSIONS. Grand

Rapids, MI:

Baker Books.

Nida, Eugene

1960 MESSAGE AND MISSION. New

York: Harper and Row. Reprinted, Pasadena: William Carey Library, 1990.

Parrinder, Geoffrey

1967

AFRICAN MYTHOLOGY. London: Paul Hamlyn.

1970 WITCHCRAFT: EUROPEAN AND

AFRICAN. London:

Faber & Faber. Peek, Philip M.

1991 AFRICAN DIVINATION SYSTEMS. Indianapolis: Indiana U. Press.

Phillips, Herbert P.

1966 THAI PEASANT PERSONALITY: THE PATTERNING OF INTER-PERSONAL

BEHAVIOR IN THE VILLAGE OF

BANG

CHAN. Lost Angeles: University of

California

Press.

Redfield, R.

1973

THE LITTLE COMMUNITY AND

PEASANT SOCIETY AND CULTURE.

Chicago:

The University of

Chicago

Press.

Smalley, W.A.

20

1974 READINGS IN MISSIONARY ANTHROPOLOGY. Pasadena: William

Carey Library.

Spiro, Melford E.

1974 BURMESE SUPERNATURALISM. Philadelphia:

Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

Stephen, Michelle (Ed.)

1987 SORCERER AND

WITCH IN MELANESIA. New

Brunswick: Rutgers U.

Press.

Steyne, Philip M.

1989 GODS OF POWER: A

STUDY OF THE BELIEFS AND PRACTICES OF ANIMISTS. Houston:

Touch Publications, Inc. Tippett, Alan

1967 SOLOMON ISLANDS CHRISTIANITY. London:

Lutterworth Press.

1987 INTRODUCTION TO MISSIOLOGY. Pasadena:

William Carey

Library.

Turner, Victor W.

1967 THE FOREST OF

SYMBOLS:

Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithica: Cornell University

Press.

1969 THE RITUAL PROCESS. Ithica: Cornell University

Press. Wallace, Anthony F.C.

1966 RELIGION: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL VIEW. New

York: Random House.

Whiteman, Darrell

1980 MELANESIANS AND MISSIONARIES: AN ETHNO-

HISTORICAL STUDY OF SOCIO-RELGIOUS CHANGE IN THE

SOUTHWEST PACIFIC. Pasadena:

Wm. Carey Library

Wilson, Bryan R. (Ed.)

1970 RATIONALITY. New

York: Harper and Rowe Publishers.

JOURNAL ARTICLES:

Dye, T. Wayne

1976 Toward a Cultural Definition of Sin. Missiology

4:1. Hiebert, Paul G.

1982 The Flaw of the Excluded Middle. Missiology

10:35-47. Horton, Robin

1962

The Kalabari World View: An outline and interpretation. Africa:

Journal

of the International African Institute 32:3:197-219. 1968 African Traditional Thought and Western

Science I & II. Africa

37:50-102.

Kraft, Charles H.

1963 Christian Conversion or

Cultural Conversion. Practical

Anthropology 10(4):179-187.

1973 Cultural Concomitants of Higi Conversion: Early

Period. Missiology 4:431-42.

Loewen,

Jacob A.

Loewen,

Jacob A.

1960 Identification

and the Missionary Task. Practical

Anthropology: 7(1):1-15.

Maynard, Ashley E.

2003 Problems of

Translation. In ANTHROPOLOGY NEWS 44(2) February

2003.

Miller, Elmer S.

1973 The Christian

Missionary: Agent of Secularism. Missiology 1:99-108.

![]()

![]() For

those of you who may not be familiar with this concept, the Evangelical

Dictionary of World Missions

describes it this way:

For

those of you who may not be familiar with this concept, the Evangelical

Dictionary of World Missions

describes it this way: