Video Translation: Opportunity and Challenge[1]

T. Wayne Dye and Tim Hatcher

T. Wayne Dye - Assistant Professor at GIAL & Tim Hatcher - Adjunct Associate Instructor. Both are members of SIL International.

Published in Global Missiology, January 2014 @ www.globalmissiology.org

My smartphone has made my daily life easier. I now have an easy way to keep contact information, take down information on bulletin boards, look up medical and other information, get a map wherever I need one, take pictures whenever I want, have a ready alarm clock, keep track of weather (a big need in Texas), and do many other things. My phone also enables me to listen to the radio or to my own music; it even lets me watch videos. But none of this revolutionized my life. Before my smartphone I also had a place to keep contact information and do all those other things; my phone just makes it easier.

In the ethnic groups where most translations are being done, however, a smartphone is much more than a convenience; it is a revolution. In much of the world, people who couldn’t afford to own one book now have access to the largest encyclopedia ever written. People who treasured the rare snapshots of family members can now own both a camera and a camcorder, and pictures are free. For the first time, those people have maps of their areas, in fact of all parts of the world. Radios, music players and video players are now part of daily life, as are contact lists, maps, alarm clocks, document scanners, crop prices in various towns, first aid and other medical information and many other things previously inaccessible.

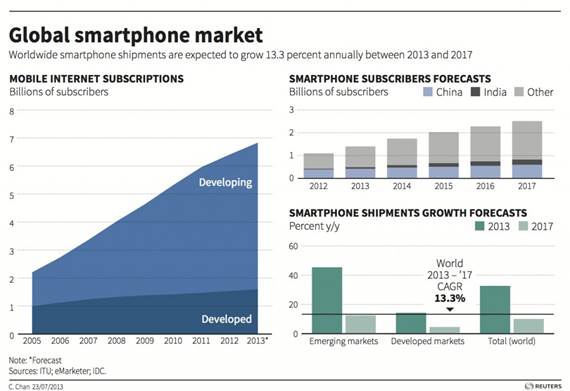

We should not be surprised, therefore, that they are buying these phones in the hundreds of millions. Business organizations that are paid by multinationals to keep track of such things are now sure that more than one billion smart phones are being sold in 2013[1]. In each of the past five years, smartphone sales have grown faster than most analysts had predicted. In fact, in 2012 most analysts predicted that smartphone sales would reach one billion in 2017, but that level was reached in less than twelve months. Smartphone usage growth is faster than any other technological development in history and it is getting faster. By far the largest part of this growth is in the less developed countries. Most of the growth is coming in the developing world (see Figure 1).

Those who still can’t afford smartphones are opting for “feature phones.” These don’t have easy access to the internet, but they do play text, audio, and video files which are easily shared via Bluetooth or Micro SD cards. At the present time, the number of mobile phone subscriptions exceeds the world population. At the end of 2102, mobile penetration in developing nations was around 89 percent of the population. Total sales of smartphones plus other mobiles are approaching two billion this year. Sales of simple mobile phones are starting to drop, however, because of the rising sales of smartphones and the fact that most people in the world now own a cell phone.

Figure 1: Smartphone expansion in the developing

world

Figure 1: Global Smartphone Market

Feature phones typically have very small screens, but many of the inexpensive[2] smartphones now on the market have 5” or larger screens. Some of those phones have larger batteries; some have louder speakers than the smartphones sold in North America and Europe. This makes it easier for media to be consumed in groups rather than individually.

This revolution provides a genuinely unprecedented opportunity to make the Bible available to the world’s minority groups. For those who can read well, Bible portions can be downloaded by one person and then shared with his family and friends. For those who can’t read, audio forms will be available, and when available, video forms can be viewed as well. All of these can be hyperlinked so that a reader can also hear Scripture or view it with little effort. All of this can be done at lower cost and with much less effort than was expended in traditional forms of print distribution, especially in those ethnic groups that were not already reading.

The most interesting of these formats is video. Video renditions of Bible portions are popular wherever people can even partially understand the language in which they are available. We therefore believe that video drama of Bible portions will quickly move from being a minor niche in Scripture distribution to a major, even central form of Scriptures for people in most language groups. Because of the significant and growing influence of video Scripture portions, this medium merits much more attention than it has received in the past. Our efforts should focus on ensuring quality in the media with which people are primarily engaging.

For a number of reasons, video will not replace written or audio Scripture formats. We do not suggest that every biblical passage should be in video. However, the use of smartphones and tablets makes it easy to combine video with written and/or audio forms of Scripture. We are in the fortunate situation of not needing to choose. We expect combinations to become be a common mode of presentation.

This discussion focuses on the prospect for video to address a number of challenges to understanding typically addressed by paratextual elements. Video forms of key passages provide essential supplements. Short videos of selected Scripture passages can provide extensive background information more efficiently and often more effectively than traditional paratextual delivery systems. The potential for video to provide necessary historical and cultural context can be better realized through cooperation between exegetes, artists, and Scripture engagement personnel. Together, they can identify which Scripture passages could benefit most from video supplementation in particular cultural groupings.

The Effect on Translation Quality

Our concern is not whether smartphone saturation will occur; we are quite sure it will within the next five years. The question is what the video medium will do to translation. At first glance, it appears to be a detriment. Video requires the translator/producer to portray not only the words, but the settings, the dress, the time of day, the weather and many more details that are required in order to portray an event in motion pictures. In a video, even the emotions of the people in the stories are portrayed by body language, intonation, position, and in other ways. A video must specify details that would be quickly rejected by a consultant if they were included in a written translation. This is a real and obvious concern that must be addressed.

However, this same feature of providing context and the character of events is also an asset. We have long known that to communicate the meaning of the Scriptures it is critical to also provide enough contextual information, enough of the background and situation of that text. Video does this with ease; in fact it can in some cases more efficiently and effectively provide an accurate picture than written translation. Video can economically portray physical contexts, human relationships and other information that would have been accessible to original readers but normally gets lost in translation. Information that is now relegated to footnotes and other paratextual elements can be seamlessly incorporated into a video.

Relevance theory helps to clarify these issues. The theory predicts that a reader/hearer/viewer will respond better to information that communicates something new and significant, or in terms of the theory, provides maximum cognitive effects. Relevance theory also predicts that a reader/hearer/viewer will respond better to information that is easier to understand, i.e. requires less effort. These two factors, cognitive effects and effort are the key to response.

The theory says that maximal perceived relevance comes when there are maximal cognitive effects with minimal effort[3]. Video provides exactly that, maximal effects with minimal effort. It enables people to almost effortlessly understand a biblical text so they can apply it for themselves. Relevance theory predicts what is seen everywhere; a Scripture passage that is no more than interesting in written form is gripping when seen on video.

Video accomplishes maximal effects with minimal effort by providing both text and paratext at the same time. It is as though the footnotes were incorporated into the text, a technique acceptable in written text only for obvious paraphrases. There is an important difference, however. When footnotes are put into written text, they often must be longer than the text itself and can easily be understood to be the main points of the passage. The focus is lost. Video provides that same information in a natural way that is absorbed but remains in the background. This ability to provide needed information without foregrounding is a strong point for video Scripture portions.

For instance, bringing a crippled man up on a roof and cutting a hole in it is senseless in most cultures. A textual description is long and difficult and a picture can help somewhat, but a video of the process can is much clearer and more efficient (see video). It does not have to be done as a separate explanation, but can be simply shown through the enacting of the scene. Such a scene includes a great deal of background information, in this case the design of first century Mediterranean houses, and it does this without foregrounding that information.

The portrayal of Jesus' flogging and crucifixion is an important example. In the gospel accounts, the description is surprisingly succinct: “But he had Jesus flogged, and handed him over to be crucified. ...then they led him away to crucify him.” The reason the language about flogging and crucifixion is so concise is that the events needed no elaboration for first century people living under the rule of the empire. They had seen crucifixions and floggings; no one had to explain to them the agonies of these Roman tortures.

Crucifixion is not practiced today, and video renditions of the gospels take that into account. Enacting the flogging and crucifixion becomes a climactic element of the presentation. These scenes in film require far more time than is taken to read the compressed gospel language. But this is necessary. It helps audiences understand things about crucifixion that they would have difficulty imagining with simple text or illustration, and exegetical objections to this are rare.

There are many other important examples. Most people in the world do not understand what is problematic about yoking together two different species of draft animals, such as a cow and a mule. A picture would not help that and explanatory footnotes would be lengthy and technical; only seeing how differently they walk can make sense of that passage (see video). [4]

Jesus called himself the good shepherd who “calls his own sheep by name and leads them out.”[5] This chapter contains extensive imagery about the relationship between shepherd and sheep. That relationship is hard to imagine, not only by people who have had little experience with sheep but also by modern sheep farmers who own thousands of sheep. A video portrayal of Jesus saying this could easily show ancient shepherds doing what he told about. [6]

Some passages lose nearly all of their strength if the hearer cannot picture the scene to which they refer. In Colossians 2:15 Paul said Christ “disarmed the spiritual rulers and authorities. He shamed them publicly by his victory over them in the cross.” The imagery is of a Roman victory parade, in which prisoners (spiritual rulers) are marched along in chains during the procession. This powerful imagery is easily understood by Westerners who are familiar with Roman conquest and the idea of victory parades, but in cultures unfamiliar with these motifs this imagery is challenging to communicate. A video introduction to this passage provides more complete understanding, more efficiently and more effectively than a simple written text or even a picture can achieve (see video). There are a surprising number of such passages for which video could clarify the background while keeping the focus on the passage.

Approximating the Original

Scholars agree that it was possible for the original readers to understand New Testament passages in the same way without including too many details partly because of the common culture of the Roman world. Tellers could count on their hearers’ ability to understand and imagine the original events because their own life contexts were so similar. Everything was already known, from flat roofs and sheep to relations between genders and the proper way for masters and servants to interact. For people outside those ancient traditions, this background information must be supplied or the stories will be poorly or even wrongly understood.

Translators of written Scriptures must make constant tradeoffs between providing background information in the text, where it too easily assumes more importance than it should, and leaving it in footnotes or counting on someone to teach it, thus leaving many readers in the dark. Relevance theory does not help us choose which approach to follow, except to remind us that too much reading/hearing effort reduces the effectiveness of a passage. Video comes closer to meeting both goals at the same time, efficiently providing the original situations without foregrounding them. Background information provided through well-crafted video Scriptures enables increased cognitive effects without increased effort.

Avoiding Video Under-translation

If this is true, what sort of video should it be? What are the challenges in video translation that arise precisely from its greater ability to communicate background and incidental information? This re-opens the question of what is accurate translation. The first responses to motion picture forms have been to aim entirely to portray the original context. Much effort has been expended to show scenes, artifacts and clothing as they must have been in the original events. That aspect can be considered reasonably successful; if Peter did not wear a robe of the color we see in videos, at least his robe is likely to have been like the ones we see.

In many gospel films, a glaring exception to accurate portrayal of physical details has been the person playing Jesus. He was a middle easterner but is often portrayed as a blue-eyed man with brown hair. Though he was a carpenter who often slept outside and regularly walked many miles in a day, he is sometimes portrayed as an ascetic with pale skin, weak muscles and peculiarly immaculate clothing. While this portrayal might be justifiable for a European or American audience, it leads to rejection by Africans and Asians much more than would a portrayal of Jesus as a working man from Palestine[7].

The more difficult challenge is to represent non-verbal behavior that expressed relationships between people, to portray these clearly enough that the meanings in an event are not lost. This is a much greater challenge for two reasons. First, much of this information was understood by the original hearers, but was lost by the time the stories were put in writing. That is the challenge we have traditionally worked on.

Secondly, even when we can deduce the physical situation, relationships and emotions from careful examination of a written text, how should those things be portrayed? Should people act as they would have as First Century Palestine residents? Unfortunately, non-verbal behavior communicates meaning in terms of a set of standardized meanings of actions and affects. There is a grammar of behavior, a particular etiquette in every culture. It influences not only overt actions like offering food or a place to sit; etiquette also determines the meaning of largely unconscious actions such as conversational distance and ways of touching or refraining from touching another person. Body language is a form of communication with its own grammar; that is why it is called a language.

If there are cultural differences in expected behavioral responses, a video translation showing appropriate body language for biblical source culture situations would actually communicate something quite different in host cultures. For instance, First Century Middle Easterners greeted with a kiss no matter the gender of the one greeted. In modern America, in the Pacific Islands and in other regions that greeting communicates something quite different than upright brotherly love[8].

The problem became clear in the reception to a major motion picture produced in 1965, Dr. Zhivago. That movie adaptation of a famous Russian novel won critical acclaim in the West, and Russian audiences were unhappy that the Soviet government did not allow them to see it. When glasnost finally gave them a chance, however, they were deeply disappointed. The movie had used British actors whose style was to portray emotion with minimal affect. That exemplified the dignity of the characters because professionals like themselves tried not to react emotionally to whatever they faced. In the scene where Dr. Zhivago parts with Laura at the rail station, for instance, the intense emotion was portrayed by small gestures and the anguished faces of people trying to avoid crying. Russian audiences, however, saw them as unfeeling rather than dignified.

While nonverbal language seldom communicates as much cognitive content as verbal language, it has two features that combine to make it communicate more powerfully. A person can refrain from speaking but he cannot refrain from expressing body language; that is communicating at all times. In addition, much of nonverbal behavior is unintentional. People typically believe a speaker’s nonverbal expressions more than his words because his body language is not so well controlled. For instance, when someone says nice words with an angry face he is likely to be interpreted as angry. When he speaks angry words with a gentle smile, he is likely to be interpreted as simply joking. Because body language speaks more strongly than speech, video portrayals of biblical events face a difficult challenge.

Some biblical films have portrayed characters with as little affect as possible, with “poker faces”, as it were. If doing that only made this video aspect a literal translation, parallel to the American Standard Version (ASV) of the written Bible, we might feel satisfied. With the ASV, readers have to deduce emotions and relationships from a text with none of the expected nuances, but at least they don’t have a text with many wrong nuances. In America and in Africa[9], a straight face communicates lack of care for others as well as lack of joy, a bad miscommunication when portraying Jesus, Paul and others as well.

In addition, many aspects of interpersonal behavior are not expressions of emotion, but simply of proper ways to interact. For instance, a person must choose whether to greet with a handshake or a bow or something else; one must greet in the way some particular culture specifies or not greet at all.

Or should we portray behavior as it would be if those events were taking place in the target language group? This portrayal will be the most accurate in meaning—but only for that target language group. Inevitably, the common practice of using just one video with different spoken languages dubbed in communicates properly in some regions but not others. To communicate accurately there must be a video version for each distinctive non-verbal language.

For example, the Jesus film often portrayed male Jews greeting with hugs to communicate camaraderie. While this is almost certainly not what actually happened, this portrayal nicely communicates brotherly love—in American culture. In India and many other Asian cultures, men do not touch, especially in different levels of society. They express that camaraderie in other ways. One must determine how it is communicated and what a hug communicates in each nonverbal language.

Possibly the most difficult challenge is to portray the emotional content of biblical scenes. If this aspect is not handled with care, it can be a negative side to video portrayals. Actors inevitably portray emotions through body language; they have no choice to omit that aspect because a “straight” face also portrays emotion. The film Matthew, which was aimed at an American audience, exemplifies the problem. The Bible says that Jesus was full of love and joy, so the actor showed him smiling nearly all the time. In a number of places that seems to us to weaken the force of what he said.

In one passage, though, that approach has resulted in an exceedingly powerful rendition that brings unity to a passage in which the words themselves do not seem to fit together (see video). In Matthew 23, Jesus is portrayed as calling the Pharisees “a nest of vipers” and “whitewashed tombs.” In this video, he did that with a catch in his voice that showed love and heartbreak, not just anger. The immediately following passage where Jesus said, “How often I would have sheltered you …but you would not (let me)” makes sense if that were his emotion. This is a powerful portrayal that brought out the hidden meaning in of a scene for a post-modern American audience for whom an angry Jesus/angry God is extremely unattractive. The point is not that the Matthew film is the best film to use in cross cultural contexts; the very things that make it work so well for many American audiences are the things that make it unusable in non-Western cultural contexts. Instead, the lesson from Matthew is that videos that present non-verbal materials appropriately for their target audience can have powerful impact.

Communicating this information is a challenge for the videographers who make them. Are different versions of biblical films needed for each of the seven thousand language groups? That seems impossibly difficult. We propose instead that there are not as many body languages, non-verbal ways to express information as the number of spoken languages. Based on personal experience in various continents, we posit that visual communication systems are similar enough throughout entire cultural areas that one video portrayal would suffice for each area. If so, then it might be possible to film activities as they might happen in each of those cultural areas, then dub in the correct speech for each language group within those areas[10].

The concept of world cultural areas has a long history in anthropology, though there are minor differences among anthropologists regarding the number and boundaries those areas. Cultural areas that immediately come to mind are sub-Saharan Africa, the Arab world, south Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, the Pacific, Latin America, and modern Europe and America. We think that with fewer than twenty video portrayals, video Scriptures would result in much better communication.

What Passages Need Video?

Video will not be the medium for the whole of Scripture –few people would watch all of Leviticus. This raises an important question about what the process should be for selecting Scripture portions for video production. Parameters quite similar to those employed by Scripture Engagement specialists for contextualized Scripture products would apply here. Passages that are of high relevance to a particular group would merit attention.

The Colossians 2:15 passage is an important example. This is a moving passage for any believer, but it appeals most powerfully to the felt needs of people in animistic contexts or where folk religious elements are present. About this passage, E. F. Scott observes that the Colossians were concerned about

the conciliation of the friendly powers by means of offerings, sacred rites, spells, and talismans, so that they would protect him against the opposing demons...but Paul insists always that this protection is offered by Christ and that all else is useless. We have a power on our side which can overcome everything that is against us. [1930]

The fears that plagued the Colossians are the same fears that plague so many people around the world, believers and unbelievers alike. The truth of Colossians 2:15 for them is this: what Roman generals did to their enemies during the thriambeuō, the triumphal procession, is what Christ did to the spiritual powers that you fear. Christ has defeated them to the point of public humiliation, and they know it. That is liberating news. When Colossians 2:15 is only available in print, that truth remains locked away due to the limitation of words. A video portrayal can communicate it easily, showing its relevance to animistic audiences. This sort of video representation should focus on passages that appeal to the felt needs of the audience.

Some Scripture passages would benefit from video presentation because they are easily misunderstood by someone from a different cultural region. Letting a paralytic through the roof or being unequally yoked are good examples where background information is essential for understanding the passage and where such information is so dense or the image so complex that it is difficult to communicate otherwise. A simple rule of thumb would be anywhere an overly-long footnote is required, a translator should consider using a video.

A New Challenge for Exegetes and Consultants

Our concern is not just that current one-size-fits-all videos hopelessly miscommunicate. We don’t do new written translations because world languages hopelessly miscommunicate; we translate because the Bible deserves to be communicated as accurately as possible. Until now, though, we have held video portrayals to a much lower standard of accuracy: use a single version and rely on explanations and viewer’s good sense to overcome the miscommunications. We can and must do better.

We have reached a time when translators and translation consultants should consider video as a primary paratextual tool for expressing historical and cultural information. When a passage requires a great deal of paratextual information, translators and consultants should call on ethnoarts consultants or Scripture engagement consultants who can produce or facilitate the production of videos to address the particular question of understanding while taking the local non-verbal environment into consideration. Scripture engagement personnel can also assist translators and translation consultants in identifying highly relevant passages for a particular group, passages that would benefit from visual renderings.

At an inter-organizational level, we recommend the production of a series of felt needs oriented videos for each of the cultural areas. An excellent example of this approach is Sabeel Media which has produced short videos for audiences in the Middle East and North Africa. These videos communicate a significant amount of paratextual information but also are careful to express things using appropriate non-verbal signals (see video example).

We further recommend the production of a series of Bible illustrations or photos from each of the cultural areas described. This does not contradict the emphasis on video in this paper. A simple video using a slide format or storyboarding is better than no video at all.

Finally, we recommend the production of life of Christ movies for each of the cultural areas. This is vital if the mission world is to move beyond the well-founded charge of inadvertently preferring Western artistic culture. Some work has already begun in this area with three Life of Christ films in India alone. Johannes Merz's excellent article addresses this need in great detail (2010). As a first step, we hope that the Jesus Film Project could overcome misunderstandings and expand its impact by producing versions suited to each culture area.

We also call on exegetes to examine biblical texts for every clue not only to the physical contexts but to the expected relationships involved in biblical events. Those relationships will inevitably be portrayed in some way in video Scriptures; we depend on exegetes and consultants to help us make those portrayals be as true to source culture meaning as possible. We depend on ethnoarts and Scripture engagement specialists to help in producing videos that accurately communicate that meaning to the target culture.

Translation checking skills can be honed to discover and check the meanings of the actions that might miscommunicate. Translation consultants carefully check whether written translations properly express relationships; the expression of those relationships by non-verbal behavior also needs to be checked. The burden of this kind of checking needs to be shared with other professionals who have expertise in etiquette and in culturally appropriate non-verbal behavior. Translation consultants should work cooperatively with ethnoarts consultants, anthropology consultants, and Scripture engagement consultants, with each sharing new insights and answers with the others.

Those are among the challenges to using video. The opportunities, though, are much greater. The worldwide spread of cell phones that can show video will enable us to bring the Scriptures into the lives of more people more effectively than ever before. Whatever the challenges, let us not miss this opportunity.

References:

Appendix: A Foundational Question for Biblical Scholars

No matter how well done, video Scriptures do not reproduce the original texts, but they seek as much as possible to reproduce original events.

Perhaps we can benefit from the insights of a South African theologian, J. A. Loubser, who views New Testament hermeneutics through the lens of media studies. He suggests that fidelity to the original events needs to be understood in the context of orality and the history of the preservation of texts.[11]. Christians in my tradition have normally referred to the “original autographs,” i.e. the original written manuscript of each book; that is in theory the lodestar. Most translators hold that true faithfulness is to those texts, not to the events that they describe.

However, in practice, all exegetes of narrative passages try to go back to the original events, the things that were done and said that the original autographs told about. When exegetes and Bible teachers describe the original backgrounds and contexts, they always describe the contexts of the events, not the contexts in which they were written. It is as though we say that what is central is the written text, but we build our Christian lives on the events that those texts report. This suggests that Loubser’s studies of First Century practices might provide insights that will help us know what comprises good video translation.

According to Loubser, for a generation the stories of New Testament events were repeated again and again with apparently no effort to write them. Finally, after a generation and when the center of Christianity had shifted away from Israel those stories were written in Greek, not even in the language in which many of them took place. This seems to have been the typical pattern in the Roman world of the First Century. An important event was told and retold so that many people knew the story and would be aware if anyone changed it. Writing that story, if it were done, was a supplement, not the primary means of preserving it accurately. Loubser argues that there was no “original” form of that kind of story; instead, there were many slight variations, with the events being considered the true original[12]. We hope these issues will be studied by those more competent in the original languages and cultures and in theology.