THE TALK LEADS THE WAY (ASTRAY): MISSION AND DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA TODAY

Jim Harries

Seminar presented at Global Institute of Applied Linguistics, Dallas, Texas, October 3, 2013, and at UK VM Conference November 14, 2013

Published in Global Missiology, April 2014 @ www.globalmissiology.org

Abstract

As the globalised English language education system grows, so does a screen of deception that fools the people in the system into believing that they are seeing the other when actually looking into a mirror. The dual aims of globalised education, to destabilise and create dependency while enabling development, are too often not perceived as contradictory. In a world in which the African sub-continent has been turned into having client status for wealthy Western patrons, objectively has become the god of the day. The lack of fit of outside inputs into indigenous African communities has become the great secret (here exposed) of our era. Missionaries or religious-change-agents are advocated as the true harbingers of development, to enable change and not destruction to be brought onto communities engaged.

Introduction

Many African nations are attempting to take global-English as the language of their own governance. This article considers the workability of this practice. It suggests that current levels of globalisation of English are rooted historically in Christendom’s hegemonic aims. One revolutionary aspect of Christianity was (and is) its universalistic claims and aspirations. As a result of these, every human being is by Christians (in theory at least) considered to have equal value, whether or not there is any known blood relation to them or dependency upon them. These and other peculiar features of Christendom, that have become routine characteristics of European life, are nowadays so widely accepted as ‘normal’ as no longer to be considered historically contingent.

This article considers some of the above, especially in relation to the globalising educational system in English. Few seem to realise ways in which the globalisation of English language education is encouraging people to be less than honest. The native-English speaking world, that leads in the acquisition and dissemination of global knowledge, acquires its knowledge of the majority world from people who have spent years learning how to respond ‘properly’ to questions they are asked and to research approaches made to them. Research on the majority world increasingly ignores translation issues.[1] The whole world can appear surprisingly European. Meanwhile, as the development machine that is informed by globalised education methodically grinds away at indigenous people’s sensibilities, so-called religious issues are given secondary status.

Globalised English-Language Education

The globalised educational system seems to be growing in leaps and bounds. In Anglophone Africa, as in much of the world, it is predominantly in English. What are the implications of the resulting occlusion of ‘local truth’ for global development and for Christian mission? I propose that this scenario is resulting in a screen of deception that is occluding a great deal of the reality of Africa and the majority world from the sight of people in the West.

Diagram A

The screen of deception, illustrated in Diagram A, arises from peoples having made and making enormous efforts to know how to talk in correct ways. That is, to talk (and write) in ways that please Americans and Brits. That is to say; they are learning the ‘right’ answers; whether or not those answers make sense to them, come from their hearts, or have any local fit. Non-Western people’s efforts at learning the ‘right answers’ in English (often by rote[2]) are receiving enormous financial backing from global bodies, as well as at times from the church. An important question for us has to be – how will a way through this screen of deception be found? Before we move on to answering this question, a few more observations are in order.

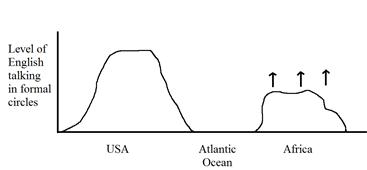

By way of simplification, I will compare the USA with Africa in the following diagrams:

Diagram B

Diagram C

Diagrams B and C illustrate and compare what is happening in terms of material wellbeing and linguistics globally. The English used in Africa, it should be noted, is not entirely African. Although much influenced by the African context, a primary purpose for the use of English in the continent is to enable it to link up with and join in with the activities of the wider English-speaking world. Such international communication is itself not without self-interested objectives; economic and material lift or advance is in view. Adding to the reasons for the preference of English to helping them to achieve material ‘lift’ is the fact that many people in the native English-speaking world (that have been profoundly influenced by centuries of Christendom) are also in favour of this objective. Many Western nations are sufficiently strongly in favour of providing a boost in the material circumstances of people in the majority world as to be ready to contribute large amounts of 'aid' towards this achievement. Hence we get a situation such as that illustrated in diagram D.

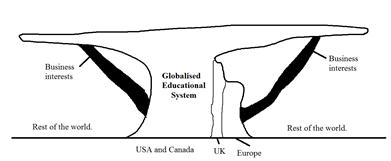

Diagram D

Theorists surmise that spreading a language from wealthy people to poor people will enable the poor people to become wealthy as have the wealthy people. Sometimes a further reason given in the interests of globalisation is to undermine the capability of poor people at fighting each other or with others.[3] While there is some truth in the fact that a hungry and confused man (not permitted to think in a way that makes sense to him (i.e. in his own language)) is often not a very effective fighting force, such an objective seems to contradict the notion that the same should be able to develop his society and economy! The above contradiction is often not realised.

The use of a foreign language does not enable indigenously driven development. It enables dependency. Inter-dependency is a very normal feature of healthy human societies. Unfortunately, the dependency that is created as a result of the use of a foreign language for one's own governance and formal purposes is an unhealthy dependency. Such linguistic dependency becomes the fount for numerous other types of dependency. It often results in giving up on the possibility of being able to do something for oneself, in favour of pleading poverty in the hope that one may gain favours from someone else: “The desire for direct financial support rather than assistance in developing their own resources and institutions is characteristic of many Africans” (Maranz, 2001:114). Such behaviour is especially likely in strongly patron-client oriented societies. Accepting the use of someone else's language is in this sense a signal that one is offering one's subservience (to a certain degree) in exchange for having one's needs catered for.[4] If one wants people to be competent, then it is much better to allow them to use speech forms with which they are familiar.

A visual-view of the globalised educational system is given in diagram E below. Here it can clearly be seen how the Western world, usually with the USA in the lead, is offering an umbrella of education to almost anyone around the world who can get a sufficient grasp of English so as to cope with the examination system that will be employed at a particular level.

Diagram E

A very noticeable feature of the globalised educational system illustrated above is its failure to connect at grassroots level. It is not supported by or sourced from the countries and peoples that it reaches. Often the purer, i.e. the more foreign, the better, such that being seen to be adapting such education to one’s own needs can be seen as corrupting it. Such education comes from one part of the world then extends, creating a great shadow over others. This shadow restricts the possibility of the successful growth of other germinating educational models or ideas; saplings die. The development of the globalised educational system has of course arisen from the more ancient task of the missionary whose role in turn developed from that of the prophet. The pre-modern approach by the West to the rest of the world was largely that of a missionary advocating a better understanding of God. The modern one has been rooted into the supposedly objective existence of reality, and offers a view of objectivity as the way forward for mankind. This is illustrated in Table F.

Diagram F A Simplified Attempt at a Pre-Modern and Post-Modern Ontology with Respect to Inter-Cultural Relationships

|

|

Pre-modern |

Modern |

|

Object of adoration |

God |

The West |

|

Means of reaching fulfilment |

The Bible and Church |

The globalised educational system |

|

Temperament |

Prayer, worship, adoration, aspiration, study. |

Prayer, worship, adoration, aspiration, study. |

|

Nature of task |

Missionary (religious) |

Development (objective) |

|

Access |

Universal |

Privileged[5] |

|

Language |

Multilingual |

Unilingual |

|

Basis for Success |

Grace |

Law |

|

Foundation in truth |

Open and Honest |

Deceptive[6] |

The two approaches above, modern as against pre-modern, have different impacts on people such as those in Africa – although those impacts also have strong parallels in each case. In each case the ‘new’ thing comes from the outside, and seems to come from above. Such is further illustrated in diagram G below, in which the top thing that seems to descend down towards (but never actually reaching or making contact with) people's indigenous knowledge can be either the globalised educational system or it can also represent English-language theological education.

Diagram G

The question for the West seems to be predominately how to do more of the above. That is: how to push more goods, education, aid, training, books, languages and computers and so on and so on into Africa. Diagram G illustrates what is often little understood. Few Westerners, it seems, have discerned this. That is, few have realised that the ‘top’ impacts don’t match or meet with the bottom content or impacts. This can be considered to be little known in a number of ways. Firstly, very few Westerners realise anyway that such a gap is being preserved in this way. Secondly, those who do realise it generally have not managed to come up with a solution to the dilemma it poses. Thirdly, because an awareness of this ‘unknown’ discourages donors, many Africans might prefer it not to be known.

Diagram G of course represents a simplification of reality. In reality, inputs from the West are from the start confused with what is already in Africa. New things are interpreted in the light of the old after all. Let me illustrate the confusion by choosing alternative words from the first two sentences of this paragraph. “Diagram in G reality represents inputs of from course the a West simplification are of from reality the ...” A sentence such as this that is a ‘mix’ of two sentences is very hard to understand! The only way of accurately knowing how an outside impact is received into a given system is to see how an outside impact is received into a given system. That is as anthropologists say, emically. It requires first knowing what the indigenous system is. At the very least, we could say a knowledge of an African language/culture complex is required if one is to know how a foreign language/culture input is to impact on an African language/culture complex. I am drawing here somewhat on a model of translation that I have long found fascinating, provided by Steiner (1998:312-318).

Towards a Solution

I suggest that there are two key components to the finding of a real solution to the above mentioned dilemmas. One, for leading inputs into a foreign community to be of the nature of religion. Two, for inputs to be into a system that is intact, to change a pre-existing ‘system’ and not to seek to destroy it so as to replace it.

The problem with current inputs by the West into the Third World is that what they are rooted in is far from firm. This has only been realised in the last 50 or so years, and the existence and impact of this truth have yet to fully penetrate academia. It was realised in the l950’s that a choice of objectivity as a basis for knowledge is (a) an arbitrary choice with no necessary ultimate basis in truth and (b) a choice that, even if made, is made in a context that is other than objective (Plantinga, 1983). The former (a) is perhaps better known. The latter (b) should be better known: it means that the nature of the impact of objectivity (i.e. science, realistic philosophies etc.), because it cannot help but be contextual, will be different in a Muslim as against Hindu, as against Primal religious background, etc. That is to say that it will be different in Africa than in Europe or America.

The fundamental basis of human living, in which science and technology inevitably find themselves being expressed, is clearly religious. Cavanaugh (2009) discovered that: “the term religions comes to cover virtually anything humans do that gives their lives order and meaning”. Beliefs that are rooted in faith provide the very vocabulary that scientific endeavours attempt to engage with to bring ‘improvements’. How they engage with them depends on how they are. No religion is written into the very nature of things (even less is science). That is to say that if we take major religions: babies are not born with Korans, Bibles, Vishnas or Confucius already in their heads. Even babies born into primal societies have to have knowledge of the desires of their ancestors taught to them by living people. Because science and technology are secondary to it, fundamental innovation must be in this religious area. That is to say in simple terms; the missionary is the prime model of effective sustainable social-cultural innovation.

My second point is a critique of the currently widely promoted system in Africa in which the new seeks to displace rather than to compliment or enhance the old. The use of European languages in Africa is a gross case of this. This system has been introduced through translation-confusion and has been powered by gross global economic inequalities. Allow me to illustrate the translation confusion through examples. Let us say that equivalents of both yes and welcome in African languages do not mean what they do in English: Terms such as Ee for ‘yes’ are in a sense grunts of appreciation for a sharing of mutual humanity rather than an acknowledgement of the correctness of what someone has said. Welcome has become a default response to an approach by innovators from Europe, particularly those who (as is invariably the case) are backed by big money. It does not necessarily hold the content of ‘welcome’ that is there in indigenous English. Failing to perceive such differences is the translation-confusion that I refer to.

Secularisation of the West has perpetuated the Christian spirit of urgency of taking the Word to all peoples, while divesting the Word of its original religious content. The original divine prerogative of Western Christendom has as a result in recent decades powered the spread of the ‘word’ of technology rather than that of Christ. Christ's Word is spread by devoted servants, whereas technology is these days perceived as being spread by money. (Something spread by money doesn't really need a traditional conversion process – everybody likes money!) Hence the West has engaged and is engaging in an almost mindless gigantic push of money and technology around the world, that ignores all intricacies of cultural difference and diversity. This has set up a power-dynamic in Africa and elsewhere in the majority world that has made it impossible to resist the self-destructive endeavour (at least if not self-destructive, it is grossly dependency generating) at displacing indigenous languages and cultures with a foreign subsidised effort at blanket-education (indoctrination) using foreign idioms. This is the globalised foreign-dependent educational system that is currently booming in Africa, which as a result of enormous outside subsidy, is resulting in the stunting of sensible but indigenous educational efforts.

Conclusion

A decline in the formal prominence of ‘organised religion’ on a global scene that has arisen as a result of secularism’s flexing its muscles, has somewhat removed the soul from the ostensive appearance of human communities. Such occlusion of the soul has enabled powerful global players to impose hegemonic educational systems. These systems operate largely without regard to their situational context. Their apparent enabling of international dialogue (without translation) has, combined with a secularist interpretive grid, deceived the world's academia into a seriously distorting myopathy. A narrow myopic way of thinking replaces God with an objectivity that is actually a product of a very specific theology and historical moment.

The outcome of the above is an oppressive global system that in its focus on the modern, including objectives such as the fulfilment of human rights that misinterpret human nature, occludes human suffering into a largely invisible private sector. Foreign subsidy underlies booming English in Africa. As well as destabilising communities, it carries the strong implicit message that African peoples are perpetually dependent clients of wealthy powerful Western patrons. The non-functionality of African communities that lies just below the surface is resulting in enormous unhealthy dependency. This article advocates so-called ‘religious or missionary engagement’ as the key to inter-cultural communication and therefore development. It advocates a transformation of rather than an overwhelming of or destruction of non-Western (as of course also Western) ways of life.

References Cited

Cavanaugh, William T. 2009. The Myth of Religious Violence: Secular Ideology and the Roots of Modern Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Kindle Edition].

Gifford, Paul. 2009. Christianity, Politics and Public Life in Kenya. London: Hurst and Company.

Maranz, David. 2001. African Friends and Money Matters: Observations from Africa. Dallas: SIL International.

Plantinga, Alvin. 1983. Reason and belief in God. In: A. Plantinga and N. Wolterstorff (Eds.), Faith and rationality: reason and belief in God (pp. 16-93). London: University of Notre Dame Press.

Steiner, George. 1998. After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. Third Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Biography

Jim Harries (b.1964) has spent his adult life (since 1988) ministering the Gospel of Christ to indigenous communities in Southern and Eastern Africa. He does this primarily in indigenous languages, from a low-level economic base, as a means of penetrating the heart of communities he meets with the Gospel. A Professor with Global University, Jim, who has a PhD in theology, is chairman of the Alliance for Vulnerable Mission (AVM - vulnerablemisison.org). He is single, but has informally adopted African orphan children.