“A CELTIC APPROACH TO REACHING ORAL LEARNERS: A SURVEY OF THE ORAL AND VISUAL STRATEGIES

USED BY THE IONA COMMUNITY CA. 600-800”

By Edward Smither, PhD

Published in Global Missiology, October 2014 @ www.globalmissiology.org

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Introduction

When remembering the history of Celtic monasticism and mission, many are quick to recognize the rich literary tradition that accompanied the movement. Indeed, such works as Patrick’s Confessions, Adomnan’s Life of Columba and The Holy Places as well as the development of a few remarkable Gospel books—the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, and the Lindisfarne Gospels—lend credence to this claim. That said, far less attention seems to be paid to the oral emphases of Celtic monastic missions and, in particular, the Iona community and their mission to Picts. In this paper, following a brief narrative of mission and background on the Pictish peoples, I will argue that Columba (521-597) and his monks, despite their significant abilities in reading and clear commitment to it as part of their spiritual growth, were quite deliberate in engaging the visual and oral context of their Pictish hosts. To support this claim, two texts in particular will be explored and evaluated for their oral qualities—St. Martin’s cross and the Book of Kells.

Background

In his celebrated work the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Venerable Bede (672-735) writes that in 565:

There came from Ireland to Britain a priest and abbot named Columba, a true monk in life no less than habit; he came to Britain to preach the word of God to the kingdoms of the northern Picts . . . Columba came to Britain when Bridius [Brute] . . . a most powerful king, had been ruling over them for over eight years. Columba turned them to the faith of Christ by his words and example and so received the island of Iona from them in order to establish a monastery there.[1]

Though the southern Pictish people had been evangelized by the Bishop Ninian (360-430) in the late fourth and early fifth century and by the Abbess Darlugdach in the late fifth century, Bede credits Columba (521-597) and his monks for being the key evangelists to reach the northern Picts in the Scottish highlands.[2] From Bede’s account, we learn that Columba came from Ireland with around twelve monks and they began by approaching the Pictish king, who was converted to the gospel and baptized. Brute responded further by giving the monks the tiny island of Iona on which to establish a monastery and mission base, while also allowing them the freedom to preach among his subjects. While their daily activities included prayer, fasting, study, and manual labor, the monks’ primary labor was regularly visiting Pictland to proclaim the gospel.[3]

Iona Abbey, built in the 12th century on the site of Columba’s original monastery

(photo: Edward Smither)

Who were the Picts? According to Cummins, they were “The first British nation to emerge from the tribal societies . . . from the fourth to the ninth century, they flourished and were the dominant power in the north [of Britain].”[4] While their origins have been debated and are ultimately unknown, over time, the Picts divided into northern and southern tribal groups in part because the southerners had embraced Christianity while the northerners remained pagan. In many respects, the Picts still regarded themselves as a single people and following his conversion, King Brute endeavored to unite the two groups as they now shared a common faith.[5] The Picts spoke a distinct language from the Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, and other British peoples and Adomnan, in his Life of Columba, indicated that the missionary abbot was forced to communicate with the Picts through an interpreter.[6] One interesting and unique feature of their ruling structure was that Pictish kings were chosen through the “female royal line.”[7] Finally, as we will discuss further, the Picts were also known for being superior artists and contributing to metal, book, and especially stone art.

Celtic Oral Strategies

Though often overlooked by scholars, one fascinating means of understanding Christian history is through the study of visual and material culture. Robin Jensen, a visual culture specialist of the early Christian period, writes: “The term ‘visual culture’ encompasses images and artifacts produced by artists or artisans that reflect aspects of civilization which may or may not be evident in other cultural artifacts such as written documents.”[8] Such artifacts, including lamps, mosaics, and architecture, offer a window into the daily life and worldview of early Christians. Discussing their value, especially in relation to written texts, Jensen adds: “Far more than mere illustration of the ideas or teachings articulated in surviving written documents, visual and material artifacts add depth and perspective to the analysis of a particular Christian group . . . one does not interpret the other, but both are understood as works of interpretation in their own terms. At the same time, they are not altogether independent and unrelated.”[9] While visual culture can tell us about church history, I suggest that there is also much to be learned about the history of mission, including clarifying the gospel using the building material of local culture such as that of the Picts.

For years, art historians have been intrigued by the Pictish contribution to Insular Art, the predominant style of art in the British Isles from ca. 600-900. Though also known for their book art, the Picts were especially adept at metal work and stone art.[10] Employing many symbols and as many as fifty different animal figures, the Picts constructed gravestones as well as monuments to commemorate their history, including things like military victories.[11] Henderson and Henderson have grouped Pictish stone art into three periods or classes that also coincide with their spiritual history. They argue that the Class I artifacts belong to the “pre-conversion” or pre-Christian period because of their “pagan symbolism.”[12] In the Class II period, the primary goal of Pictish stone art was to represent the cross, which the Hendersons regard as “a consequence of [their] conversion.” In fact, they argue that in this period, the primary function of Insular sculpture in greater Britain was “to display the cross publicly.”[13] Finally, Class III stone art contained images of the cross that were completely free of pagan images.[14]

While the three periods of stone art show evidence that the Picts accepted Christianity and were apparently growing in their devotion to it, there is also evidence that Columba and his missionary band were deliberate in using this art form to communicate the gospel. The Hendersons argue that the cross-marked stone, “originated, without a doubt, in Irish missionary work among the Picts in the sixth and seventh centuries . . . the conformity in every respect with the cross-marked stones on Iona, and in the West of Scotland generally, is in itself evidence for the period at which Christianity began, literally, to make its mark on Pictland.”[15] Simply put, Insular stone crosses communicated the essence of the gospel—the death, burial and resurrection of Christ. The Hendersons add: “when the first Irish or British missionaries introduced to the Picts the idea of carving a cross on a stone they will also have explained how the Christian symbol could function in a Christian society. It would primarily be as the embodiment of the central belief of the church that Christ’s sufferings on the cross and his subsequent resurrection gave mankind the hope of eternal life. The cross was the basic aid for instruction and devotion.”[16] In short, Columba and his monks used this key text of Pictish culture to not only communicate the essence of the gospel but also to offer the Pictish church a visual catechism as it instructed new believers.

St. Martin’s cross (photo: Edward Smither)

While these initial stone crosses aided the monks in communicating the gospel through a medium familiar to the Picts, over time other crosses were constructed that communicated more of the overall story of Scripture. One example is St. Martin’s cross, a large stone work built between 750 and 800 at Iona, which stands there in the present day. At the center of the cross, the birth of Christ is depicted with Mary holding the baby Jesus. Continuing down the cross, the stories of Daniel in the lions’ den, Abraham raising his sword to sacrifice Isaac, David fighting Goliath, and David playing his harp are also communicated. The latter image seems especially contextual as David is joined by another musician playing triple pipes. In short, in viewing St. Martin’s cross, Pictish visitors to Iona could contemplate the meaning of the cross and also engage in a visual Bible study.[17] In many ways, the Celtic crosses served the same function of stained glass in medieval European cathedrals—communicating the narrative of Scripture through visual means for those who could not read and effectively becoming the “poor man’s Bible.”

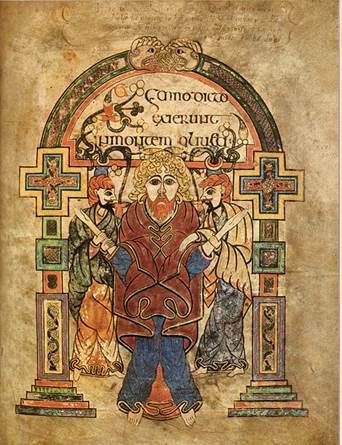

The gospel was further communicated through one of the most famous artifacts of Insular Art, the Book of Kells, which was developed at Iona around 800. Though it only included the four Latin Gospels, a mix of both Old and Vulgate Latin, the work was much longer because of its beautiful calligraphy and many pages of colorful illustrations, especially those relating New Testament stories.[18]

Let us consider how the Book of Kells was influenced by Pictish art and, in turn, how it became a significant means of clarifying the gospel for the Picts. First, though a book, the style of art in the Book of Kells greatly resembles the features of Pictish stone art. The many crosses displayed throughout the book look like the crosses on Iona and around Pictland. According to Meehan, their function was to offer the reader a regular reminder of the death, burial, and resurrection of Christ.[19] Second, the Book of Kells is rich in animal imagery, including snakes, birds, and lions, which also resemble the animals used in pre-Christian Pictish art. These are especially important for conveying the person and work of Christ. Though depicted as a human being at his birth, Christ is rendered as a calf in his death, as a snake shedding skin in the process of his resurrection, and as a lion in the resurrection. Also, he is presented as a peacock because of his perfect, authentic flesh and later as a fish because of having gone through the waters of baptism. The last image was probably particularly meaningful to those near the island of Iona where fishing was still a way of life.[20] The human depictions of Christ also seemed very contextual as he was rendered “blond, youthful, and radiant”; that is, he looked very Pictish and Irish in the pages of the Book of Kells.[21]

It should be remembered that the Book of Kells was forged in a liturgical and catechetical context. Though small and portable enough to be carried on mission trips around Pictland, the Book of Kells probably stayed at Iona for the most part. However, as there were many visitors who came to the island, including those who participated in the liturgical assemblies, the visual themes conveyed in the books (the person and work of Christ, the cross, as well as other Eucharistic imagery) served to instruct new believers.[22] In turn, these Bible stories and their truths traveled throughout the Scottish highlands in a manner that was meaningful and relevant to Pictish culture and their visual and oral memory. Obviously, one of the reasons that the Book of Kells was effective in this way was because of the excellent and beautiful work of art that it was. In 1185, Giraldus Cambrinsus commented to that end: “if you take the trouble to look closely, and penetrate to your eyes to the secrets of the artistry, you will notice such intricacies, so delicate and so subtle, so close together, and well-knitted, so involved and bound together, and so fresh still in their colorings that you will not hesitate to declare that all these things must have been the work, not of men, but of angels.”[23]

Christ’s arrest depicted in the Book of Kells amid cross stone art (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Conclusion

In short, the influence of Pictish stone and book art is quite apparent when we study the symbols of Pictish Christianity, particularly artifacts such as St. Martin’s cross and the Book of Kells. Further, because Columba and the generations of Ionan monks that followed embraced these art forms, it seems evident that they were being deliberately contextual in their mission strategy to convey the gospel through the building material of local Pictish culture. This is further remarkable because of the highly literary context and the importance placed on books and reading at Iona.[24] In their communication of the gospel and teaching Scripture, the monks did not insist that the Picts learn to read Latin, Gaelic, or even develop a Pictish alphabet; rather, they identified with the Pictish host people by communicating through their visual vocabulary through stone and book art. Though the Book of Kells could be read by the literate (those who could read Latin), it could also be read and studied by those who imbibed the visual images that captured the story of Scripture.

As we reflect on the testimony of the Columban monks in light of later mission history and today, at least a few remarks can be made. First, nineteenth- and twentieth-century Protestant missionaries, who went into the world with communication strategies largely appropriate for the literate, would have done well to reflect on the choices and strategies of the Celtic monks in Pictland, which may have helped to avert some miscommunication that occurred in this period. Second, proponents of oral strategies today ought to be encouraged that their emphasis in mission has supporting voices from the history of monastic missions. While there is much innovation today in reaching oral learners, the sensitive and contextual work of Columba’s monks ought to humble us as well. Finally, the Celtic monks, who were clearly well read and educated in Scripture and theology, valued communicating the gospel in a medium that could be understood. This should serve as a model today for every follower of Christ striving to make the gospel understood—communicating to non-believers accessibly and free of Christian insider language, offering Scripture in a version (medium or reading level) that can be understood, and finding appropriate bridges to the gospel from non-believer’s host culture.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Ed Smither currently serves as Professor of Intercultural Studies at Colombia International University. Ed earned a PhD in Historical Theology from the University of Wales (UK) and a PhD in Intercultural Studies from the University of Pretoria (South Africa). In addition to a number of scholarly and practical articles, he has written two books, Augustine as Mentor: A Model for Preparing Spiritual Leaders and Brazilian Evangelical Missions in the Arab World, and translated François Decret's Early Christianity in North Africa from French. Currently, Ed is working on two forthcoming books, Mission in the Early Church and Rethinking Constantine.