|

A Profile of

North American Messianic Jews: A Study Conducted by Jews for Jesus

Andrew

Barron and Beverly Jamison

|

|

Published in Global Missiology, April 2015 @

www.globalmissiology.org

|

|

|

There are Jewish people in North America who have come to

faith in Jesus as Savior of the world and as the Messiah of Israel. Our

interest is in surveying a group of these people in order to understand their

lived experience.

From June 1, 2013, through December 1, 2013, Jews for Jesus

carried out a broad study of Messianic Jews in North America. This study was a

follow-up to a similar study conducted in 1983. The 2013 study involved a

sample of 1,567 respondents and, like its predecessor, covered a variety of

aspects through quantitative questions covering age, family background,

education, religious observance and vocation.

The purpose of this study is to aid those of us involved in

the wider messianic community. Our challenge is to critically understand our

evolving movement; to provide resources and stimulate strategies for outreach,

fellowship and edification.

Through this study we explored:

1.

The representation of the experiences of a group of Jews who believe in Jesus

2.

How this group of Jewish people experienced cultural influences during

their decision to follow Jesus

3.

How one generation’s experience compares with

another

Qualitative questions covered observance of religious

traditions, Jewish and general beliefs and values, and Jewish identity. A new

section of analysis covered the respondent’s experiences as they heard and

responded to the gospel. The distinguishing range of this study and a

comparison of its findings were made with those of the previous study (Jews for

Jesus, 1983) the Pew study (Portrait of Jewish Americans, Pew Research, 2013)

and the Steinhardt study (American Jewish Population Estimates, 2012).

The Pew Research Foundation published their report on

American Jews, which contains valuable comparison data for the American Jewish

community and, where appropriate, the general U.S. population.

American Jews say they are proud to be Jewish and have an

awareness of belonging to the Jewish people. Nevertheless, Jewish identity is

changing in America, where one in five Jews (22%) now describe themselves as

having no religion. The percentage of U.S. adults who say they are Jewish when

asked about their religion has declined by about half since the late 1950s and

currently is a little less than 2%. The number of Americans with direct Jewish

ancestry or upbringing who consider themselves Jewish, yet describe themselves

as atheist, agnostic or having no religion, is rising and is now about 0.5 % of

the U.S. adult population.

The changing nature of Jewish identity stands out sharply

when these results are analyzed by generation. Ninety-three percent of Jews in

the aging generation identify as Jewish on the basis of religion; just 7%

describe themselves as having no religion. By contrast, among Jews in the

youngest generation of U.S. adults, 68% identify as Jews by religion, while 32%

describe themselves as having no religion and identify as Jewish on the basis

of ancestry, ethnicity or culture.

This shift in Jewish self-identification reflects broader

changes in the U.S. public who increasingly shun religious affiliation. The

share of U.S. Jews who say they have no religion (22%) is similar to the share

of religious “nones” in the general public (20%), and religious disaffiliation

is as common among all U.S. adults ages 18-29 as among Jewish Millennials (32%

of each). Sixty-two percent say being Jewish is mainly a matter of ancestry and

culture, while 15% say it is mainly a matter of religion. Even among Jews by

religion, more than half (55%) say being Jewish is mainly a matter of ancestry

and culture, and two-thirds say it is not necessary to believe in God to be

Jewish.

Compared with Jews by religion, however, Jews of no religion

are not only less religious but also much less connected to Jewish

organizations and much less likely to be raising their children Jewish. More

than 90% of Jews by religion who are currently raising minor children in their

home say they are raising those children Jewish or partially Jewish. In stark

contrast, the survey finds that two-thirds of Jews of no religion say they are

not raising their children Jewish or partially Jewish–either by religion or

aside from religion. (Pew, 7-8)

The Steinhardt Social Research Institute

(SSRI) produced an expansive study of the Jewish population in North America in

2012. There are an estimated 6.8 million Jewish adults and children in the

United States: 4.2 million adults self-identify as Jewish when asked about

their religion. Nearly 1 million adults consider themselves Jewish by

background and other criteria. There are an estimated 1.6 million Jewish

children among adults who self-identify as Jewish by religion. Just over 1 million

(24%) are aged 65 years and older. They are more than twice as likely as other

Americans to be college graduates. The portrait of American Jewry described by

the 2012 SSRI findings is of a population, at least numerically, in ascent.

(SSRI, pp 7-8)

Abstract of Findings

The

statistics from this survey have been compared with the previous survey of

Messianic Jews in 1983 as well as other available demographic data. Messianic

Jews in North America have a wide-ranging Jewish temperament. Messianic Jews say

they are proud to be Jewish and have an awareness of belonging to the Jewish

people. A majority consider themselves part of the Jewish people, based on

nomenclature preferences and lifestyle. More than 90% feel an association with

Jewish tradition, observe some Jewish practices and life-cycle rituals, and

mark at least some of its festivals.

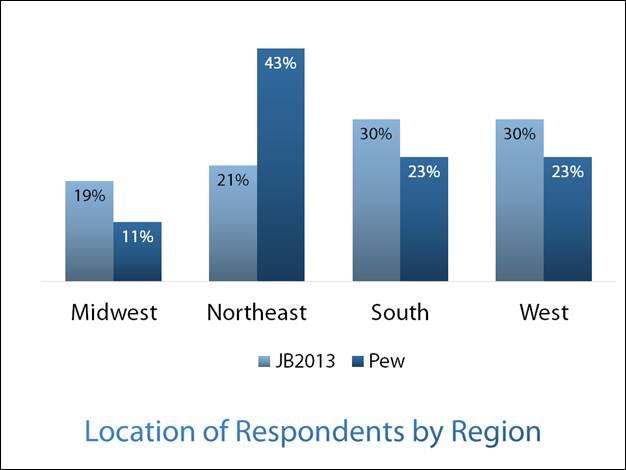

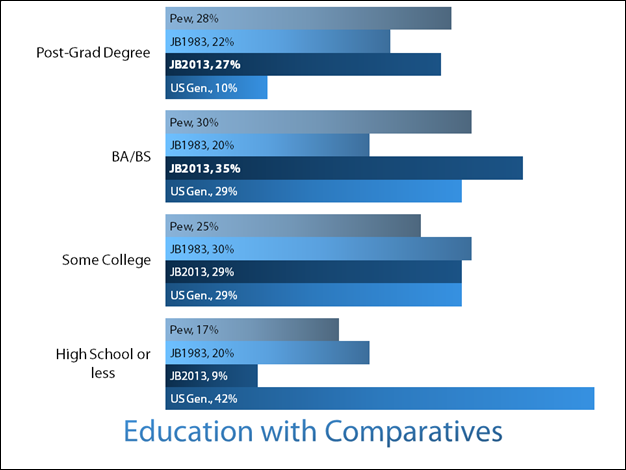

We see in Tables 10, 11 and 12 that Messianic Jews are

overrepresented in our survey in education credentials and professional and

specialized vocations. Respondents are underrepresented in the Northeast and

overrepresented in the South, Midwest and West. Seventy-five percent of

respondents married people who are not Jewish.

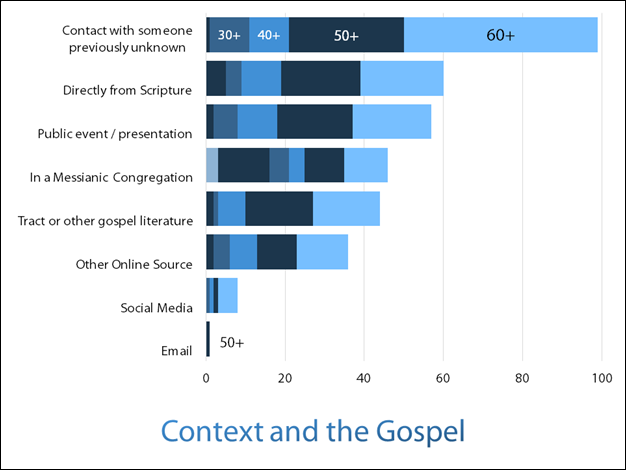

Respondents in Tables 14, 15 and 16 are hearing the gospel in

the marketplace. As expected, the most common way for someone to hear the gospel

in the Jewish community is in direct conversation. However, there has been

growth in the numbers who hear the gospel in a church, a Messianic congregation,

and in conversation with a relative.

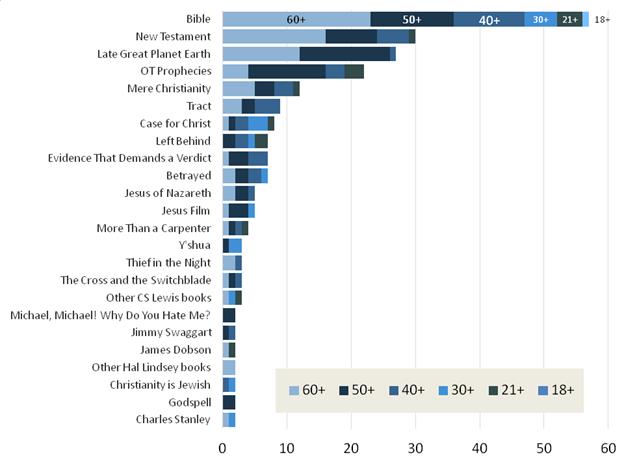

We see a consistent representation of the influence of the

Bible, New Testament and prophecy across age groups. The Late Great Planet

Earth by Hal Lindsey is not significant among responders under 50. CS

Lewis is the most well-represented author of influence across all the age

groups.

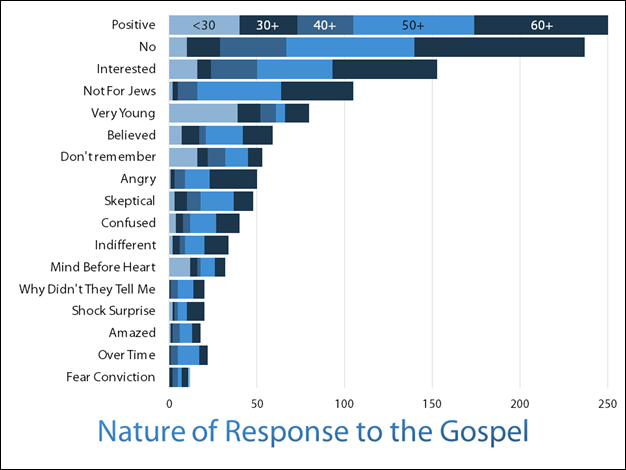

An equal number of respondents responded positively and

negatively when they first heard the gospel. The median age that Jews hear the gospel

is 17 and the median age of becoming a Messianic Jew is 22. Across the age

group we see this five- year period as typical. We can see that older

responders responding to the gospel trended in a negative way whereas younger

respondents exhibited similar but less severe reactions. Jews who hear the gospel

confront issues of loyalty to community, culture, family, and friends. They

think about the Holocaust and are afraid of change. As these people think about

Jesus and his relationship to the Jewish people, they read the Tanakh

and the New Testament. They confront the words of our prophets. They read books

and they talk to God and their friends. They are convicted of sin.

Lifestyles, values, and identity of most of our respondents

reflect efforts to maintain a connection to Jewish distinctiveness and

tradition, on the one hand, and choice, on the other. The results show a broad

consensus that reflects a representative commitment to the wider Jewish character,

culture and continuity.

“Jewish

identity is complex and fluid.” (SSRI, 24) We see Messianic Jews and their

families express their Jewishness in a variety of ways. The relationship of the

Messianic Jewish community to the North American culture at-large and the

Jewish community in particular is a reflection of these myriad of options.

Socio-psychologist

Bethamie Horowitz is a research assistant and Professor of Jewish Education at

NYU. She has conducted research about major issues and problems facing the

Jewish people for more than two decades. Horowitz says that “Jewishness unfolds and gets shaped by

the different experiences and encounters in a person’s life. Each new context

or life stage brings with it new possibilities. A person’s Jewishness can wax,

wane, and change in emphasis. It is responsive to social relationships,

historical experiences and personal events.” (Horowitz, 2000 p. viii).

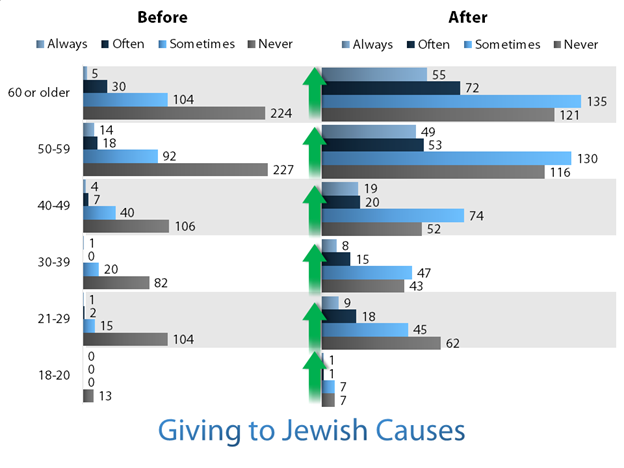

Messianic Jews, orient themselves in new and refreshing ways

to their Jewish community. We see increases in various Shabbat activities and observances,

interest in Hebrew, Israel and participation in Jewish issues that affect Jews

around the world. They become more generous in their attention and resources to

issues of Jewry. Most significant is the increase in awareness in their interest

in giving to Jewish causes, going to Israel and tikkun olam. This

Hebrew phrase that means "repairing the world" (or "healing the

world") advocates our common responsibility to heal, repair and transform

the world.

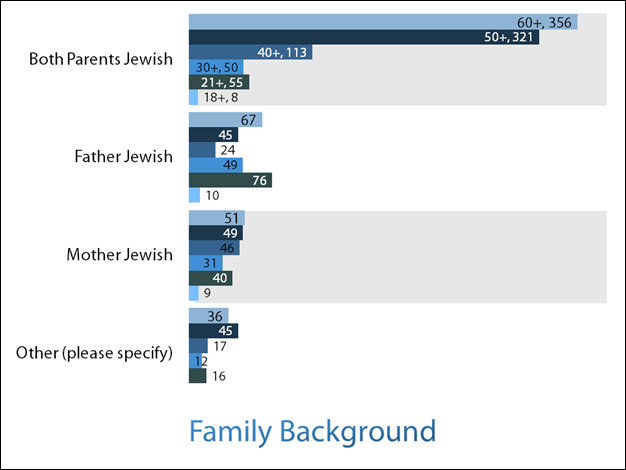

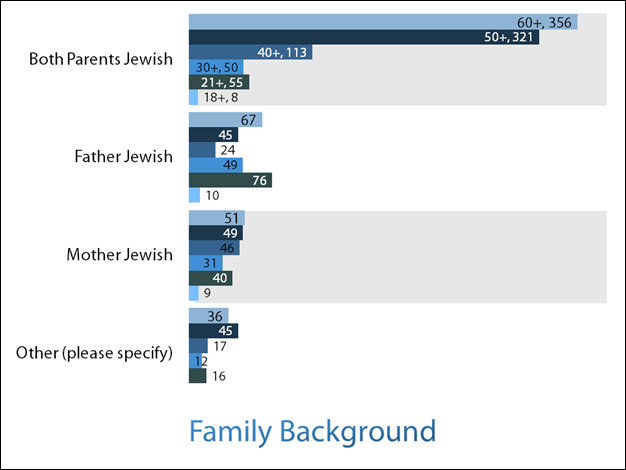

The survey opens with a question about the background that

defines the respondent as Jewish. More than 75% of those in the fifty and older

decades report both parents Jewish. For those born after 1980 we report just

under one-third of them came from households with both parents Jewish. This is likely

influenced by the larger number of second generation Messianic Jews in the

youngest respondents, reflecting mixed marriages of Messianic Jewish parents

Table

1 Family Background

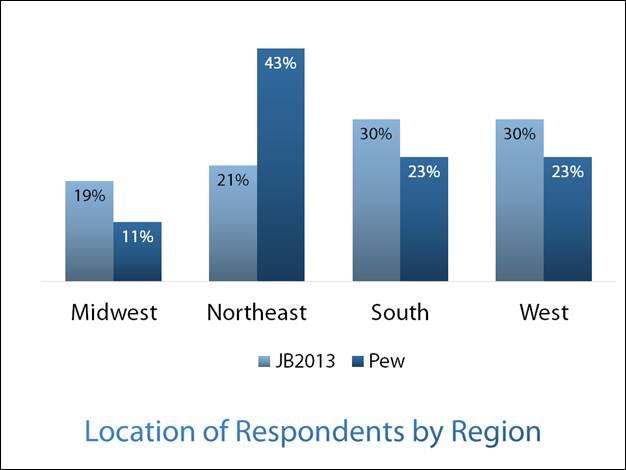

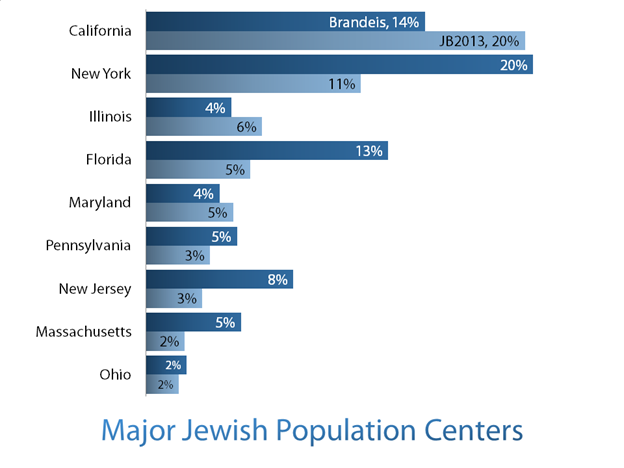

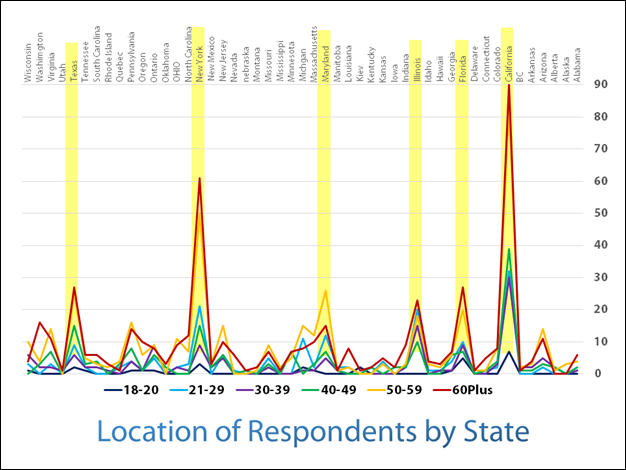

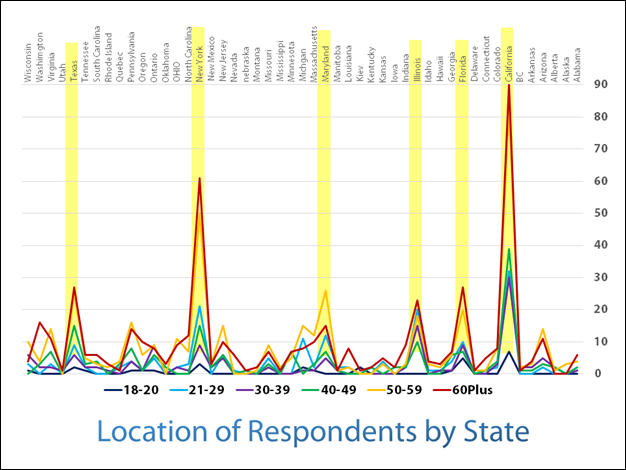

These questions involve the location of the respondents. The

larger states and larger Jewish population centers have the highest number of

Messianic Jews. California and New York have the largest communities, followed

by Texas, Illinois, and Florida. The DC metro area also represents strongly. The

Brandeis study (SSRI, 16) provided population estimates for the major

population centers. We see Messianic Jews overrepresented in the West and

Midwest and South and underrepresented in the Northeast.

Table 2. Location of

respondents by state

Table 3. Location of Respondents

by Region

Table 4 Major Jewish

Population Centers

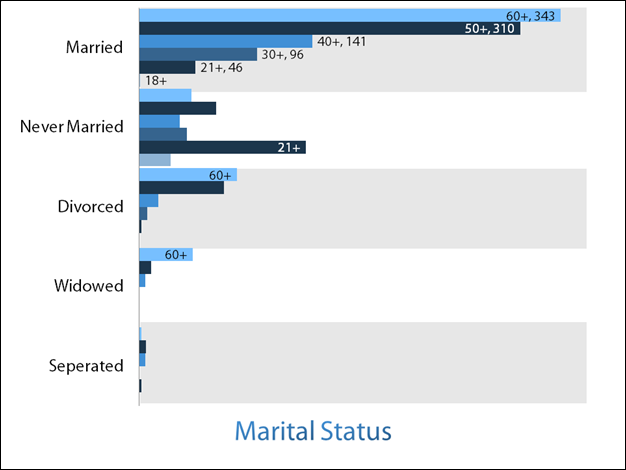

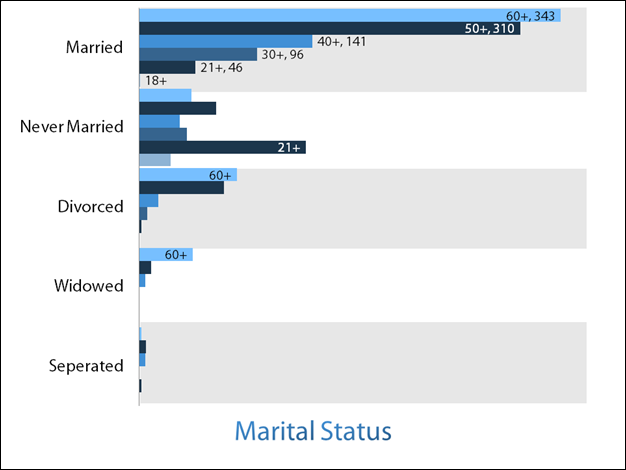

The variation between married and single reflects the

expected larger number of never-married among the 29-and-under populations.

The small numbers of widows / widowers is also a reflection of the age

categories on the whole.

Table 5 Marital Status

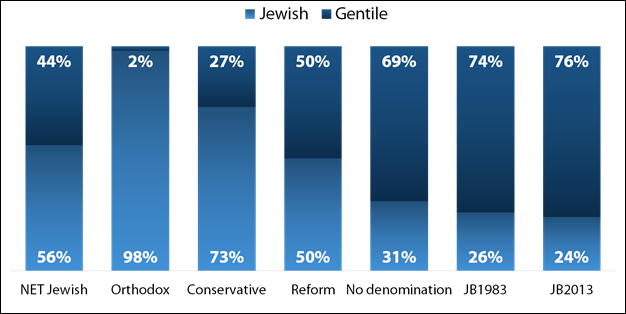

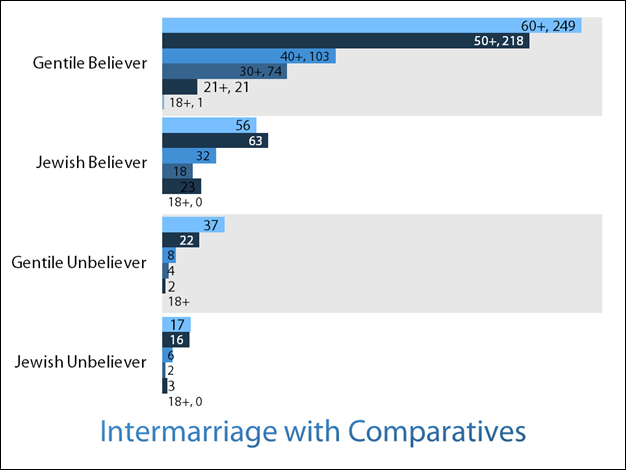

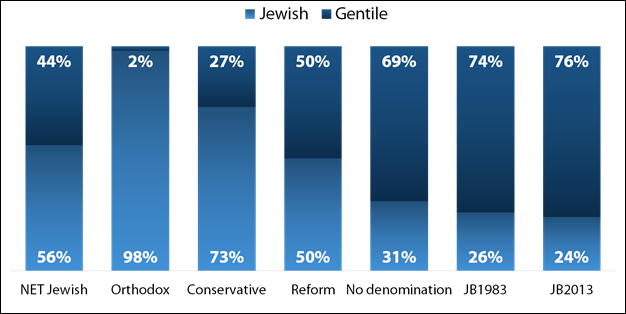

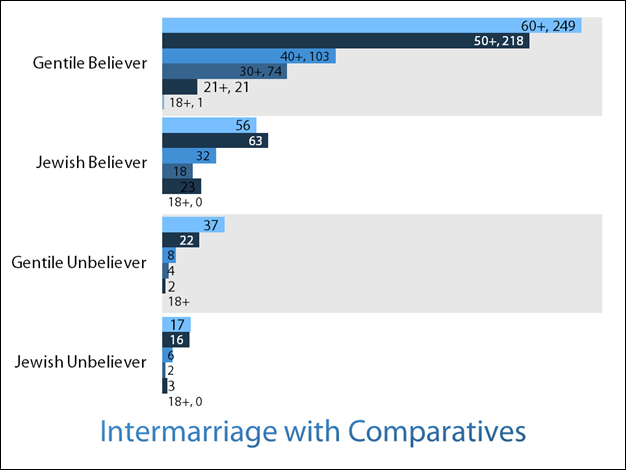

These results show that the intermarriage rate is higher in

the Messianic Jewish community than in the categories listed in the Pew study.

There was a slight increase from 1983 to 2013, though not as much as in other

categories in the general Jewish population. Table 7 indicates a small change

in the intermarriage trend among second generation Messianic Jews.

Table 6. Intermarriage

Table 7 Intermarriage

with Decadal Comparatives

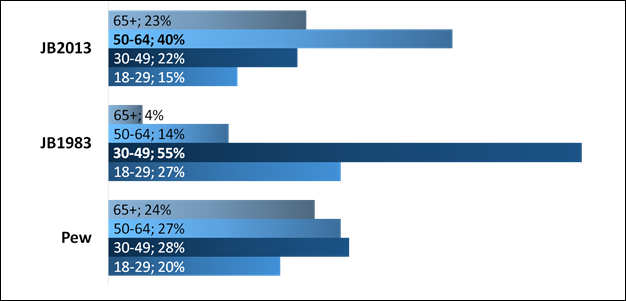

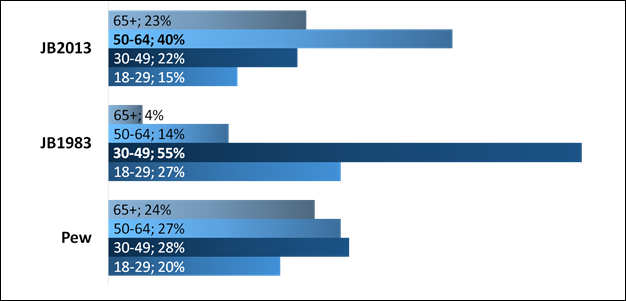

The majority of the respondents were in the older

decades, though there is still a reasonable representation of the younger

groups as well. The Pew study has a more even distribution across their chosen

age categories, while the 1983 and 2013 surveys reflect the evolution and

growth of the movement, with more pronounced spikes in each survey.

Table 8 Age Group

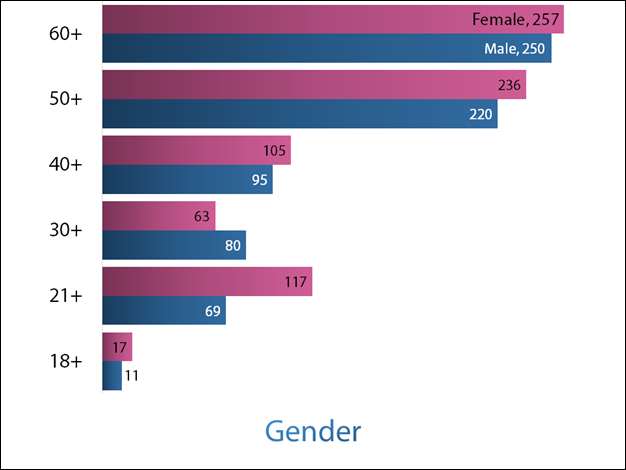

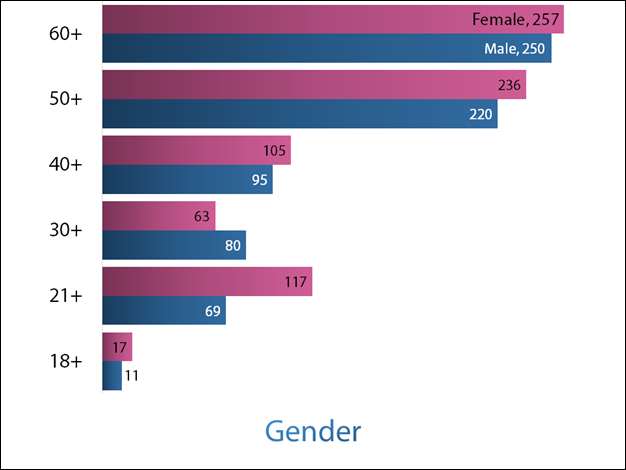

The gender of the respondents was evenly distributed, with

52.4% female and 47.6% male. The ratio varied slightly with the decades. 49%

of American Jews are male, 51% female, the same as the total U.S. population

Table 9 Gender

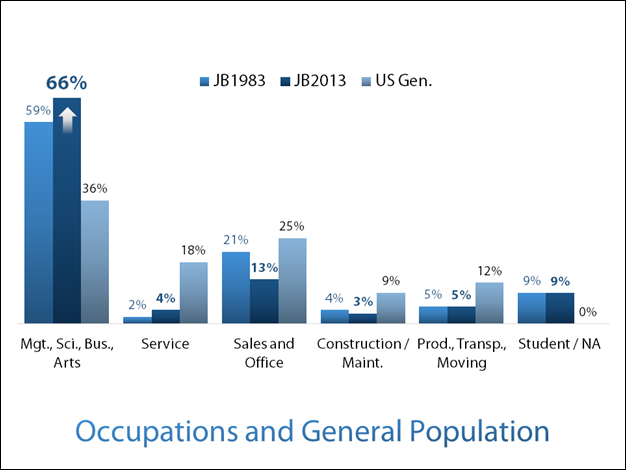

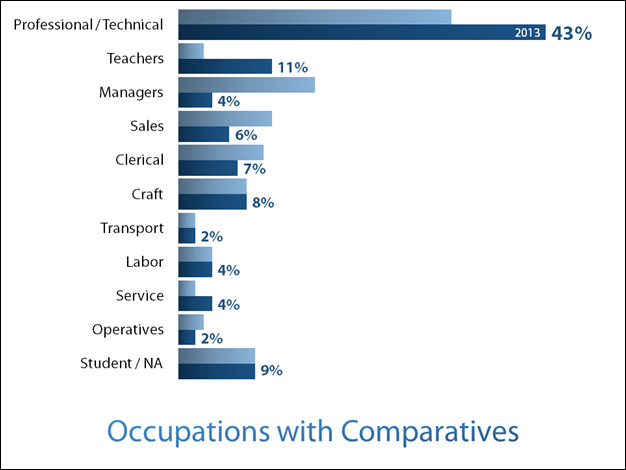

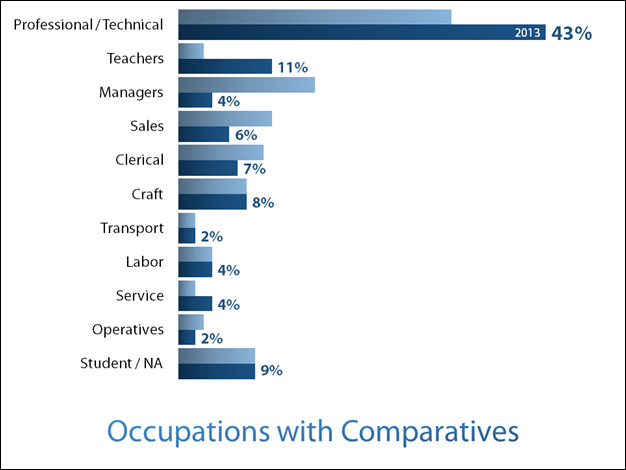

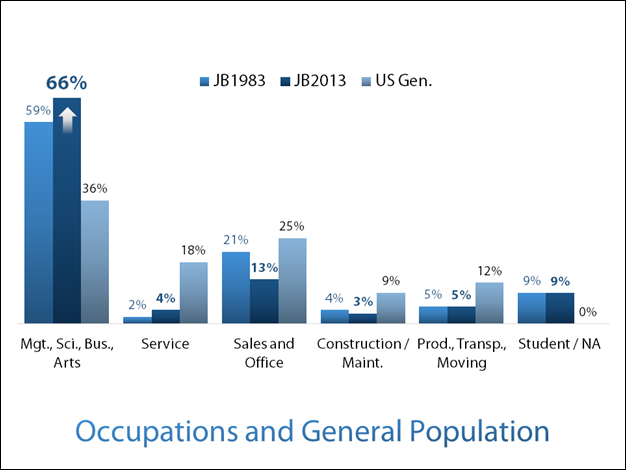

We compared 2013 with 1983 results. A wide range of options

were given. The first graph uses the categories

provided in the Jewish Believer surveys. The Jewish Believer population has a

higher representation in the Management, Science, Business, and Arts categories

than the general population, with an additional increase from the 1983 study to

the 2013 one. The second graph normalizes the responses in order to compare

them with categories used in a survey by the U.S. Census Bureau. Some of this

additional increase probably reflects career path growth due to the increased

representation in the higher age brackets.

Table 10 Occupation

1983 vs. 2013

Table 11 Occupation and

U.S. General Population

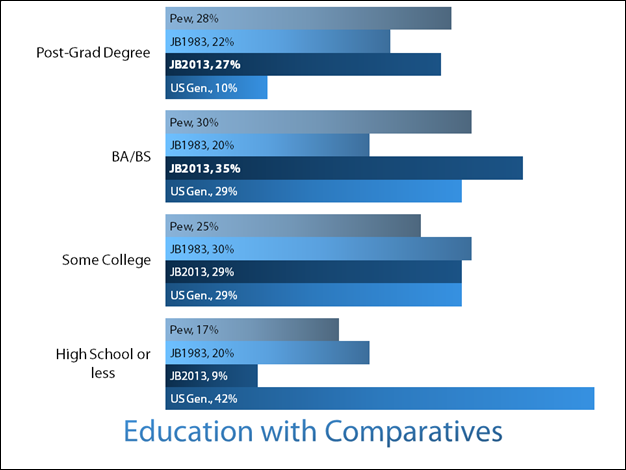

There is a commitment to education by Messianic Jews that is

more significant than in the general population and at par or greater than the

wider Jewish community, as shown in the following graph. We compare the Pew

survey with the 1983 survey, the most recent survey and US General population.

Table 12 Education

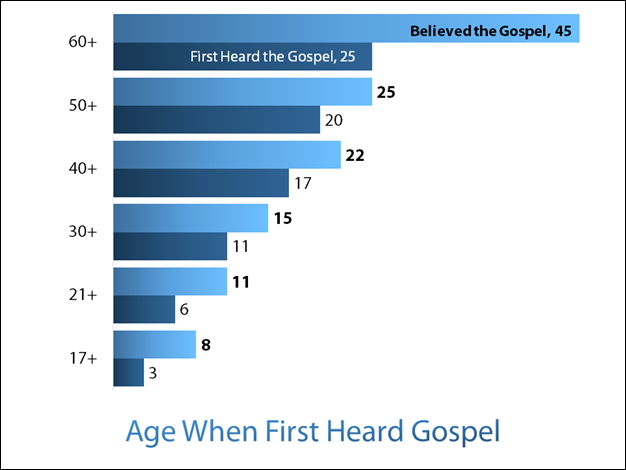

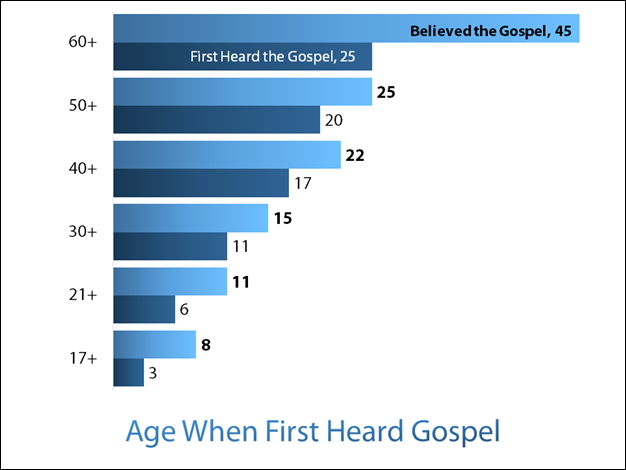

Overall population: Median age is 17 for first hearing the gospel

and 22 for becoming a Messianic Jew. Table 12 breaks the age down by decade. As

expected the average age rises with each decade, but across all decades, most

people had heard the gospel by age 25, though there were still a number of

respondents who did hear the gospel later in life. And while the medians were

17 and 22, the averages were significantly higher, indicating that people do

respond to the gospel even when hearing it for the first time at much later

ages.

Table 13 Age and the Gospel

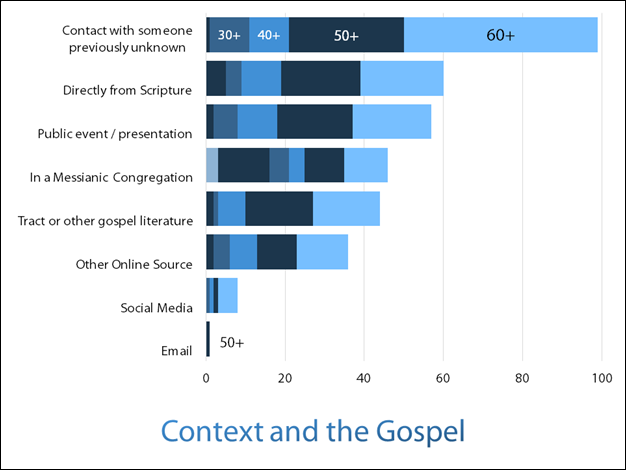

These questions ask the source and context in which the

respondent first heard the gospel broken down by decade. As expected, the most

common way for someone to hear the gospel in the Jewish community is in direct

conversation. However, there has been growth in the numbers who hear in a

church, a Messianic congregation, and in conversation with a relative.

Table

14 Context and the Gospel

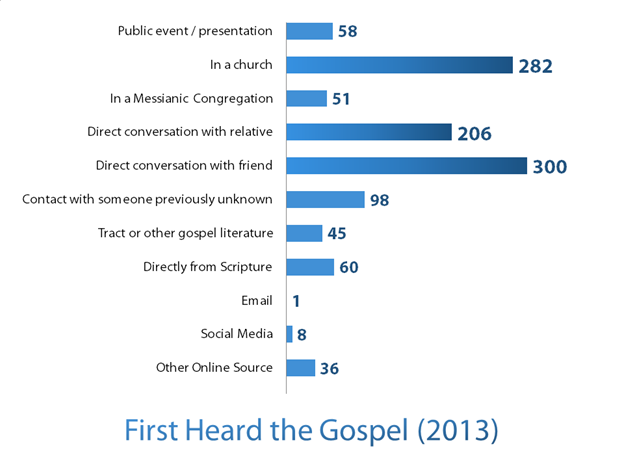

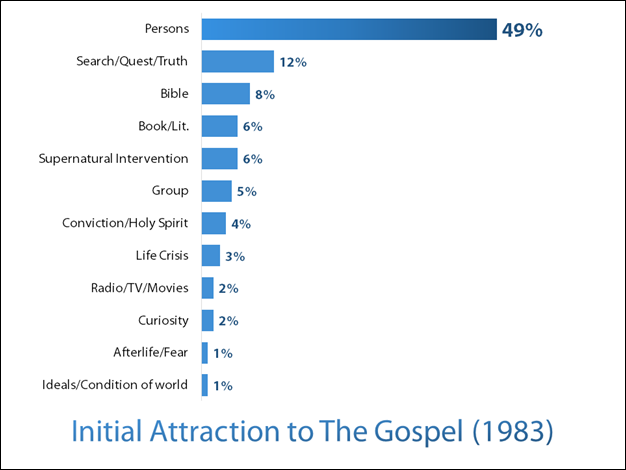

Tables 15 and 16 ask the same question of source and context

in different ways. Although the question was asked differently in the two

surveys, the importance of personal interaction around the topic of the gospel

was very important, with respondents in the 2013 survey indicating the

conversation with friends, relatives, or strangers accounting for the majority

of the means of hearing (with a congregational setting, Messianic congregation

or church being the next most prevalent). The 1983 survey indicated that people

were the strongest influence.

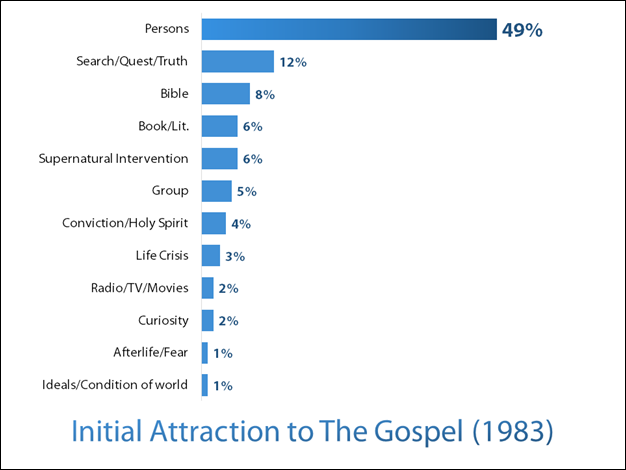

Respondents were asked to provide narrative here as well. We

can see that older responders responding to the gospel trended in a negative

way, whereas younger respondents exhibit similar but less severe reactions.

Table 15 First Heard the Gospel

Table 16 Initial

Attraction to the Gospel 1983

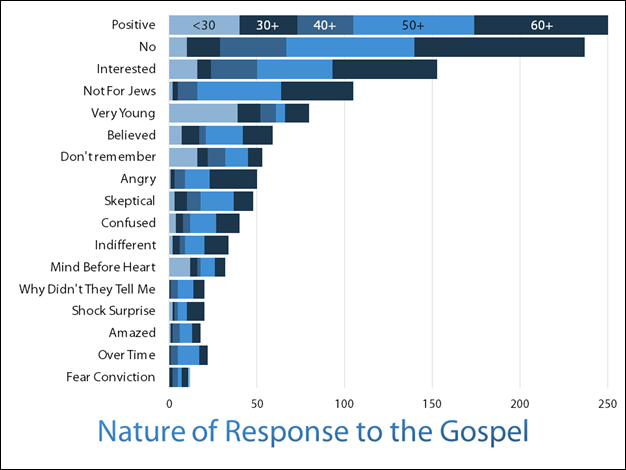

Table 17-18 look at the nature of the response, actions

taken and convincing. These are categories that were applied to narrative

responses. We tried to capture the essence of the reaction. There is a mixture

of positive and negative responses across the age groups.

Table 17 Nature of

Response when you first heard the Gospel

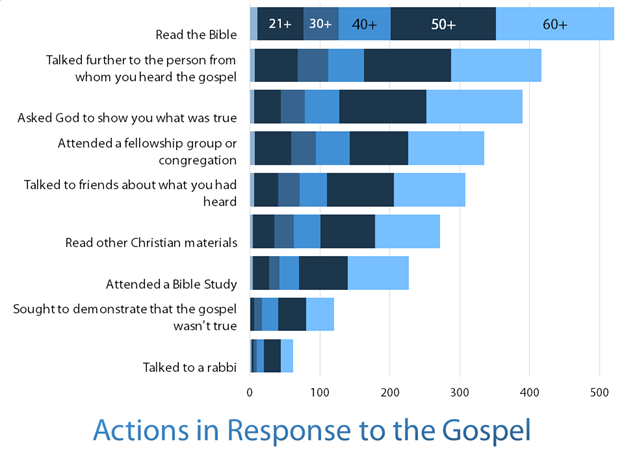

Table 18 offered respondents multiple options with regard to

actions taken after hearing the gospel. The trend indicates respondents

attempting to refute or confirm, using the Bible and friends as resources. Each

response was well represented across the age groups.

Table 18 What Actions

did you take after you heard the Gospel?

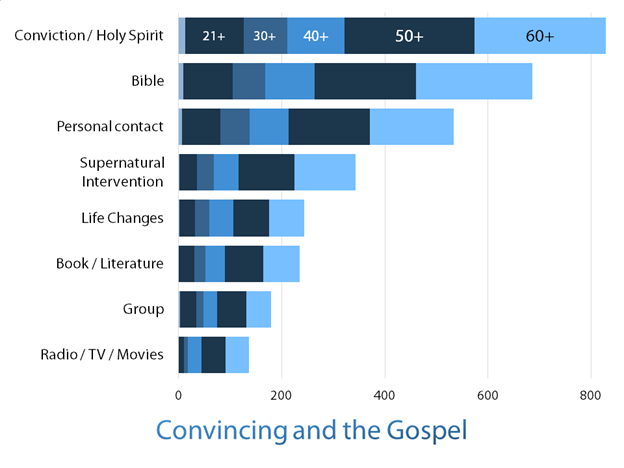

Respondents for Table 19 were able to select multiple

options. We see again as in Table 18 that responses were well represented

across the age groups.

Table 19 What helped to

convince you of the Truth of the Gospel?

Table 20 indicates a consistent representation of the Bible,

New Testament and prophecy across age groups. The Late Great Planet Earth

is not significant amount responders under 50. C.S. Lewis is the most well-represented

author across the age groups.

Table 20 What Book or

Movie influenced you?

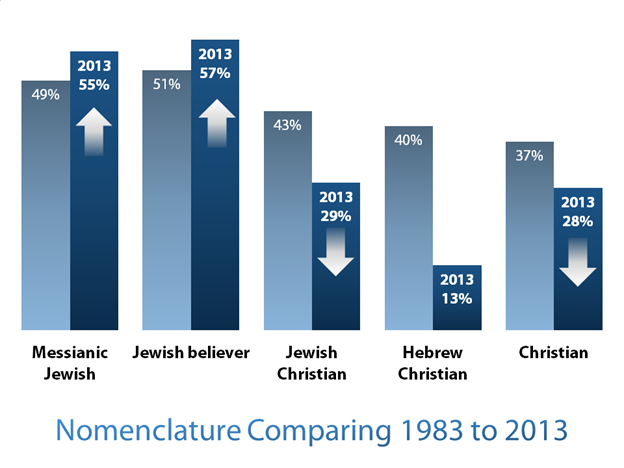

This graph answers the question how Jewish believers in

Jesus identify themselves. There has been some significant trending in the last

three decades away from “Hebrew Christian” and with an increase in

identification as either “Jewish believer” or “Messianic Jew.” Respondents were

allowed to choose more than one option.

Table 21 Nomenclature

Comparing 1983 to 2013

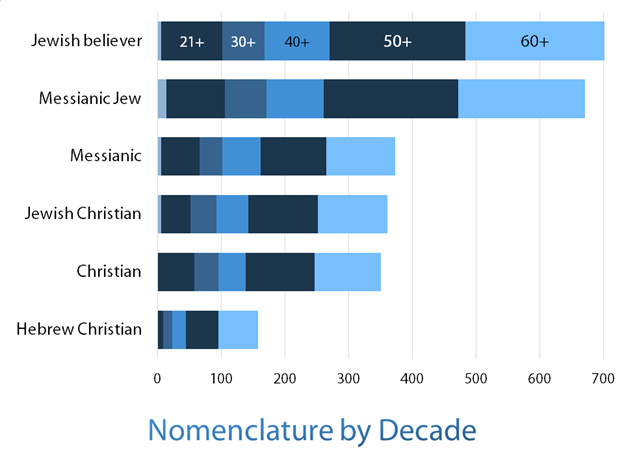

These results across the decades show a consistent pattern

of some label that maintains Jewish identity. Respondents were able to select

multiple options.

Table 22 Nomenclature

by Decade

The next section attempts to show the wide variety of ways

that Messianic Jews participate in the Jewish world. We see a consistent

pattern of respondents taking a renewed interest in participating in and

relating to their Jewish world in a variety of ways and with a variety of

commitments. We see diversity and choice in patterns that reflect a commitment

to the Jewish world in the face of the pressures of modernity. More than 90%

feel an association with Jewish tradition, observe some Jewish practices and

life-cycle rituals, and mark at least some Jewish festivals. Before and After

questions endeavored to show if any orientation and participation in the Jewish

world changed. We also attempted to see if commitments to the Jewish world were

altered after their decision was made.

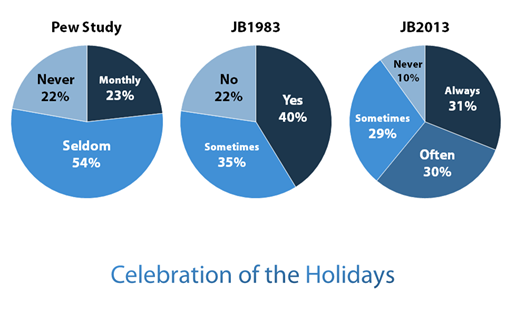

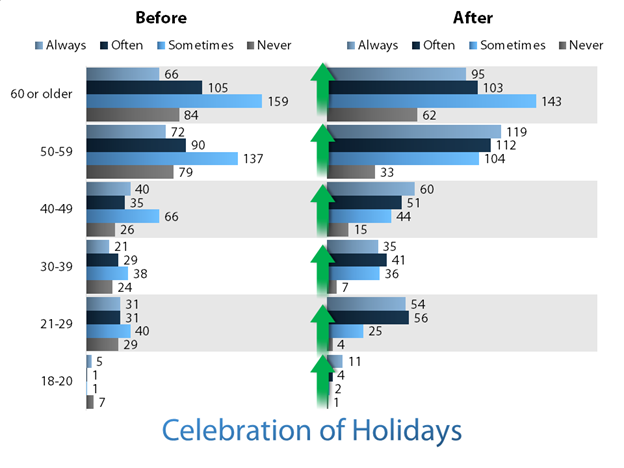

We see in Table 23 respondents in 1983 and 2013 say that

they are oriented to and participating in Jewish life in a more substantial way

than respondents to the Pew study.

Table

23 Celebration of Holidays Comparatives

Table 24 respondents show by decade how celebration of

Holidays was impacted after becoming a Messianic Jew. We see a trend across age

groups towards a participation in Jewish life

Table 24 Celebration of

Holidays Decadal Before and After Becoming a Messianic Jew

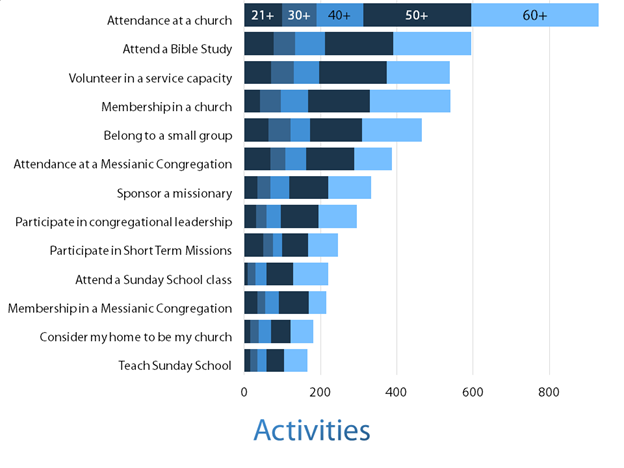

Table 25 asks the respondents to list what activities they

participate in on a regular basis in their Messianic Jewish life. There is an

even response across age groups, and respondents were able to choose more than

one activity.

Table 25 Activities

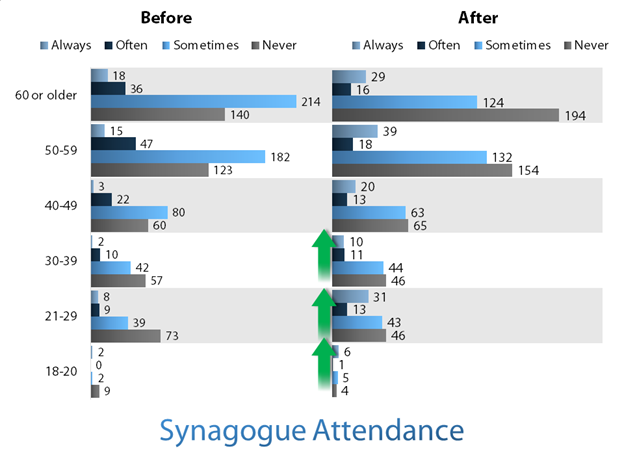

Respondents here and below indicated participation in and

orientation to a variety of activities, interests and causes before and after

becoming Messianic Jews.

Table 26 asks the respondents to speak to their participation

in synagogue life outside the Messianic Jewish community. Patterns indicate an

orientation, especially in older respondents, away from this practice. We do

see, however, a consistent pattern of Messianic Jews in all age groups

participating in and worship at local synagogues.

Table 26 Synagogue

Attendance

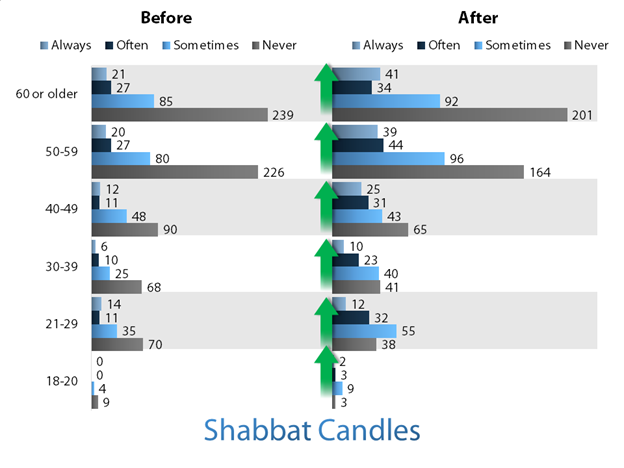

Table 27 asks respondents if Shabbat is recognized in the

home through the lighting of Shabbat candles. We see a consistent increase in

orientation across age groups towards this practice.

Table 27 Shabbat

Candles

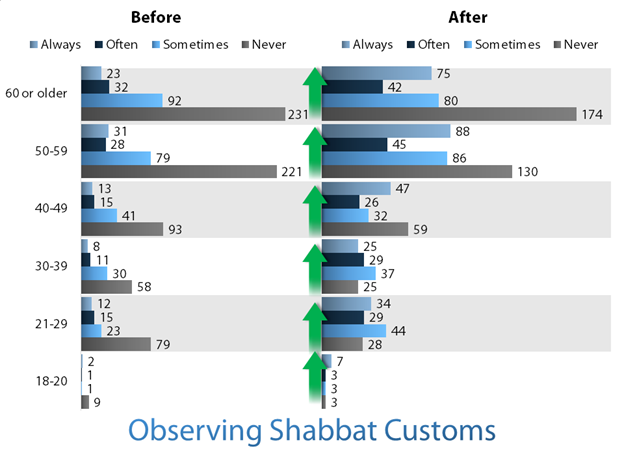

With regard to the general observance of Shabbat, and

without providing specifics, we see again a consistent increase in orientation

across age groups towards this practice.

Table 28 Observing

Shabbat Customs

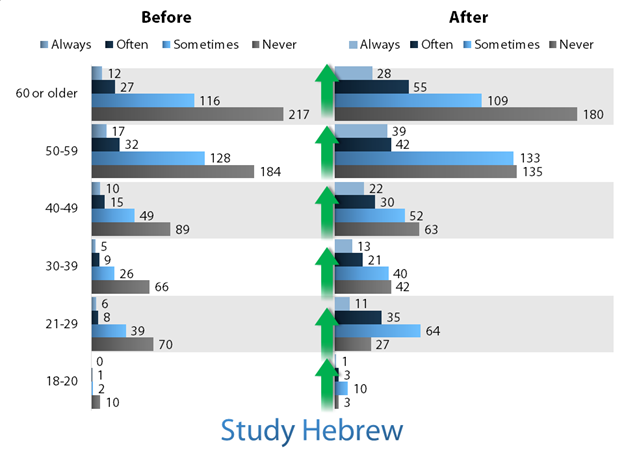

With regard to the study of Hebrew, and without providing

specifics, we see a consistent orientation across age groups towards this

practice.

Table 29 Study Hebrew

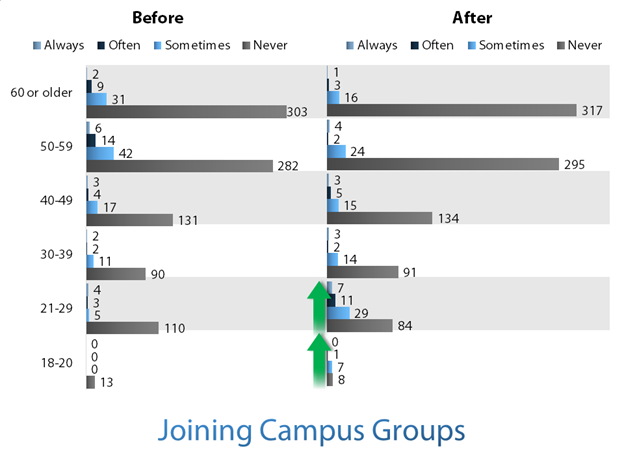

Table 30 respondents show a consistent pattern of

participation in older and younger ages. We speculate that these groups were

not available to older respondents or that the older groups participated in

more extemporaneous and impromptu groupings. We note respondents under 30 trending

towards participation in campus groups.

Table 30 Joining Campus

Groups

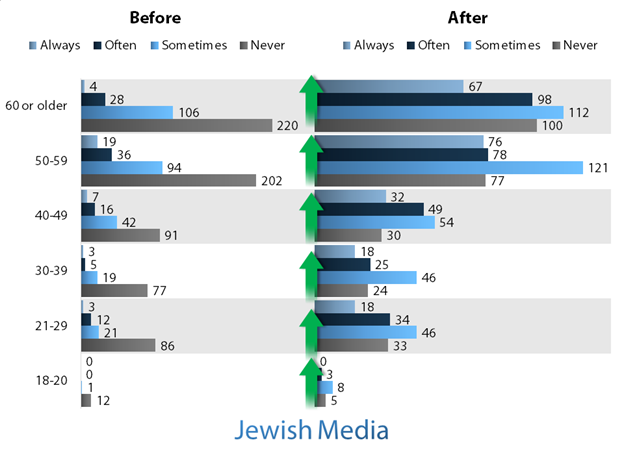

With regard to accessing and reading Jewish media, and

without providing specifics, we see a consistent increase in orientation across

age groups towards this practice.

Table 31 Jewish Media

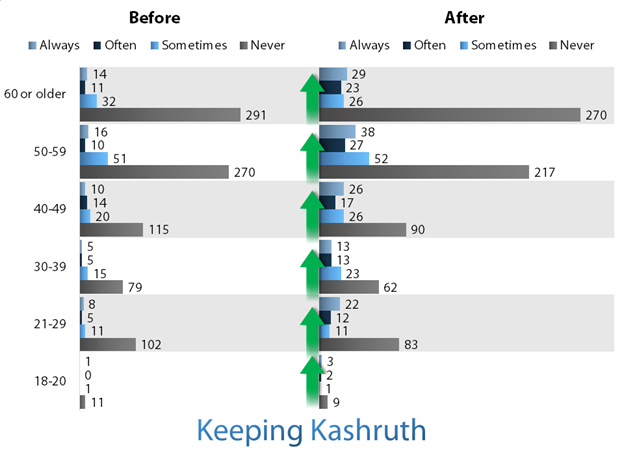

With regard to traditional Jewish food observances, and

without providing specifics, we see a consistent increase in orientation across

age groups towards this practice.

Table 32 Keeping

Kashruth

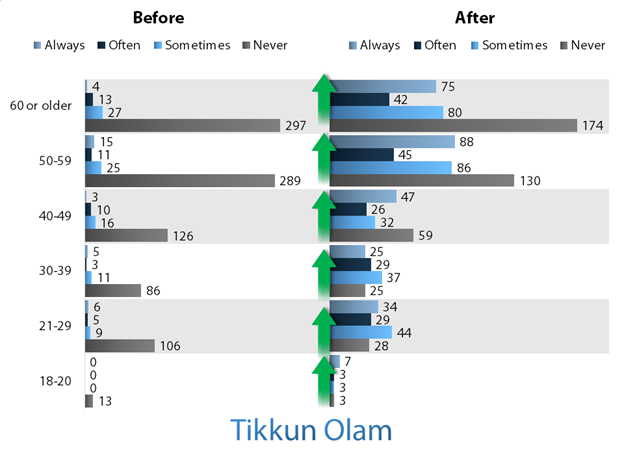

With regard to the Jewish value of tikkun olam (repair of

the world), and without providing specifics, we see a consistent and very

significant increase in orientation across age groups towards this

practice.

Table 33 Tikkun Olam

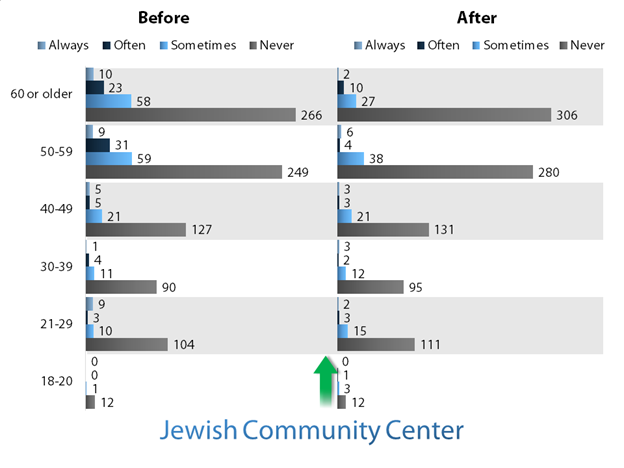

With regard to participating in Jewish community centers,

and without providing specifics, we see some decrease across age groups towards

this practice.

Table 34 Jewish

Community Center

With regard to giving to Jewish causes, and without

providing specifics, we see a consistent and significant increase in

orientation across age groups towards this practice.

Table 35 Giving to

Jewish Causes

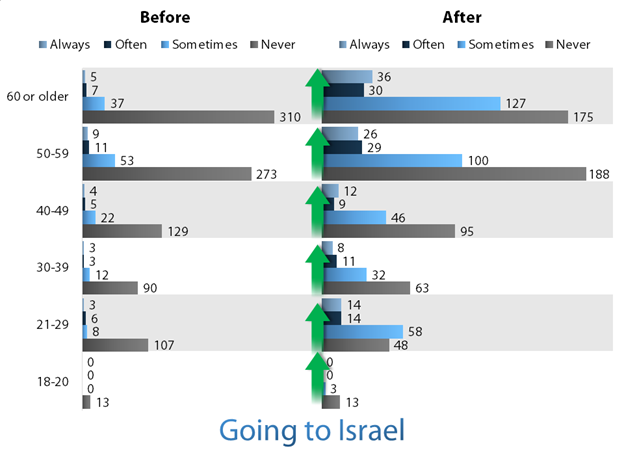

With regard to traveling to Israel, and without providing

specifics, we see a consistent and significant increase in orientation

across age groups towards this practice.

Table 36 Going to

Israel

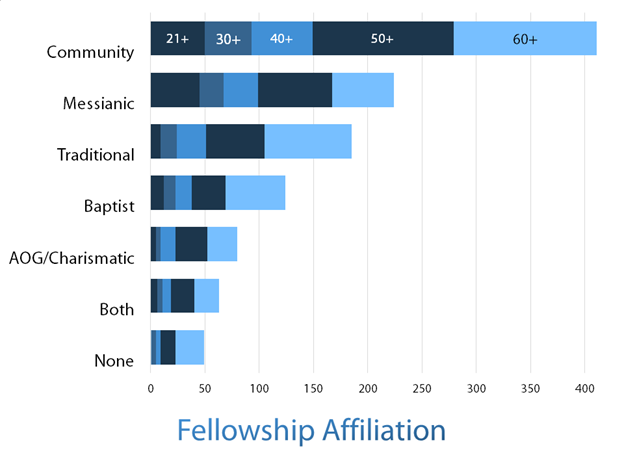

Table 37 asks the respondents to list the churches or

congregations they attend. This was asked in order to get a more concrete

sense of congregational affiliation and present attachment to fellowship. We

then grouped the responses in order to make a more meaningful comparison. In

most cases, the type of church or Messianic congregation was reasonably clear.

Five percent of respondents indicated attendance at both a

Messianic congregation and a Christian church of some other denomination.

In most cases, the denomination was reasonably clear from

the name, but in some cases we made some assumption about the category.

Messianic congregations, Baptist churches, and charismatic churches were each

grouped into their own category. The Traditional category included Roman

Catholic, Episcopal, Methodist, Lutheran, Presbyterian, and similar

denominations. The community category includes community churches,

non-denominational churches, and some of the more recent “movements” in which

non-denominational churches have emerged as affiliated congregations in

multiple cities.

Table 37 Fellowship

Affiliation

Qualitative results are more elusive. Narrative responses

were broken down by common themes and significant statements which yielded

patterns that were sometimes easily and sometimes more difficult to discern. In

assessing and analyzing this part of the research, we examined narratives that

show patterns of experiences in relationships and pressures related to the

decision-making experience. We tried to develop categories of information that

would lead to an understanding of the common experience of the participants.

Questions on pressure

The comments on family rejection covered several types of

internal pressure. Some of the following comments represented common themes

weighted across age groups but clustered in the above 50 group.

Loss of important relationships: ‘It became a battle

between the comfort of my life and a good relationship with my family or

choosing Jesus.’ ‘ “My dad and I were already in a strained relationship; this

most likely would make it worse.”

Direct rejection: “When I first went to church, mom

kicked me out of the house and made me choose to either leave church or leave the

house...” “Since I come from a very powerful family, I was concerned they would

try to have my children taken out of my care through legal channels, but I was

prepared to face any judge since freedom of religion is our right”. “My family

cut me off and mourned my death. They wanted nothing to do with me for a

while, then after eight months or so they accepted it, but not happily.”

Fear of telling family: “Had a huge fear of my dad

finding out” “Was afraid to tell my parents, family members.”

Fear of disappointing family: “My dad was always rich

in his Jewish beliefs and I feared disappointing him, but what I felt in my

heart was true. My mom was raised Jewish but she went into this New Age belief

that borders on cultish like..” “I only knew of one family that were Jewish

believers while growing up. They were considered the ‘weird family’ in the

neighborhood. I felt like I would be considered the black sheep of my family

and that they would be disappointed in me..” “I didn't want to disappoint my parents.”

Ridicule from family: “When I finally got the courage

to tell my dad, he laughed at me and said that belief in Messiah and heaven is

like being on drugs. My family thinks I am nuts, but they are still my family.”

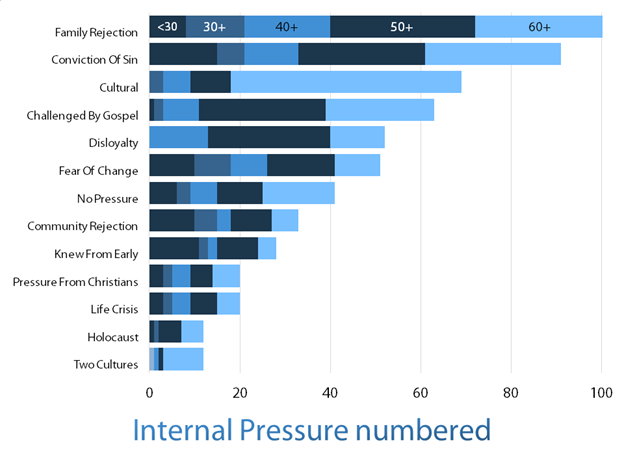

As expected, family rejection was the most

often-cited item, with related items of community rejection, cultural pressures

and disloyalty. Also, the most frequent mention of the Holocaust was among the

age groups for children of Holocaust survivors, with a smaller incidence in the

age groups of their grandchildren.

There was an increased incidence (particularly

proportionately) of those who knew of the gospel from an early age among the

youngest two categories, representing the increase in second-generation

believers.

Conviction of sin ranked high. This was followed by

those who indicated they were challenged by the gospel in various ways.

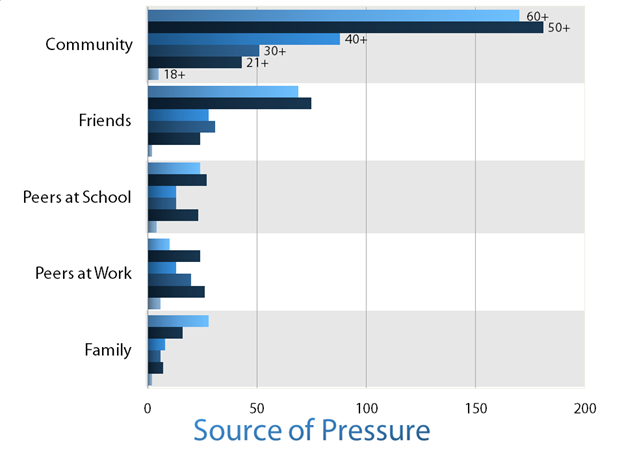

Participants were involved in

a complex pattern of relationships that were affected by this decision making

process. Respondents were able to cite multiple sources of pressure. We would

define community as the formal Jewish community and family of the

respondents. Based on the number of responses, we still see similar patterns in

all age groups.

Table 38 Source of Pressure

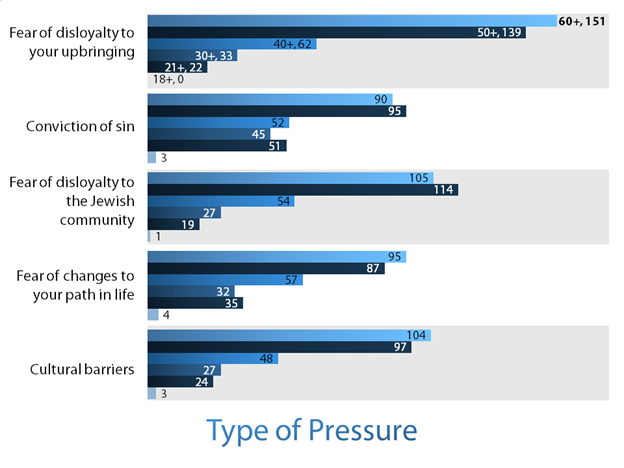

Table 39 was multiple select. There is a consistent pattern

of experience in all age groups.

Table 39 Type of Pressure

Table 40 asked respondents for a narrative response. Family

reaction and conviction of sin were the most prevalent expressions seen in the

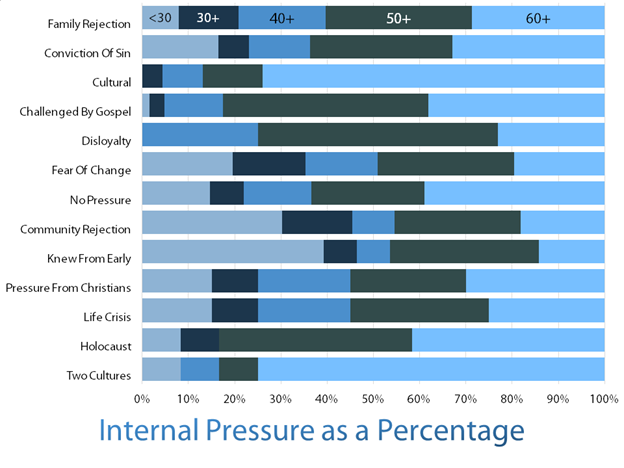

stories.

Table 40 Internal Pressure

numbered

Table 41 asked respondents for narrative response. Older age

groups indicate the largest percentage response to being pulled between a

variety of social and cultural values.

Table 41 Internal Pressure as

a Percentage

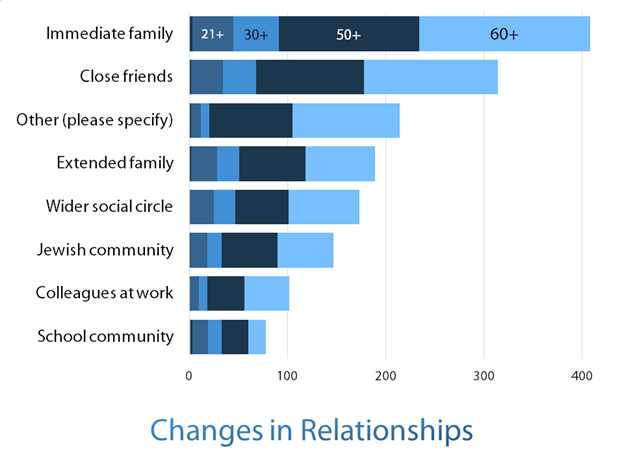

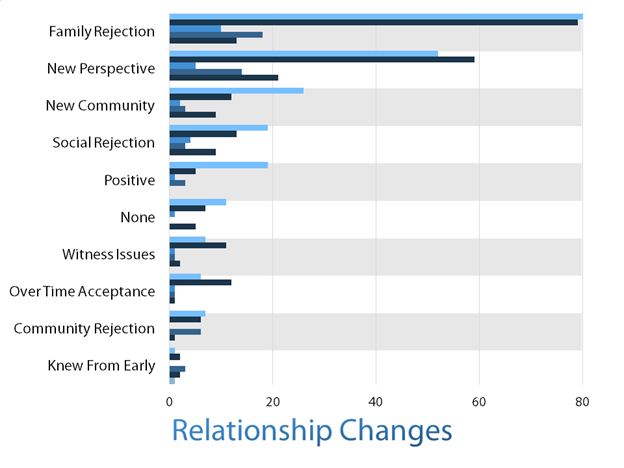

Table 42 provided respondents multiple choices. They were

able to choose more than one selection. There is an even distribution among age

groups in these expressed changes

Table 42 Changes in

Relationships

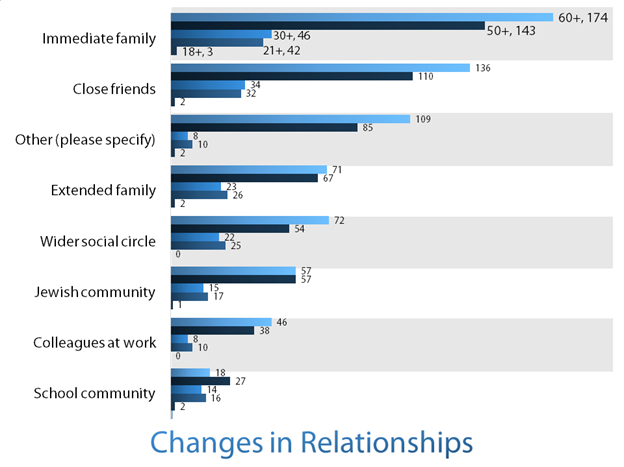

Table 43 shows the same data as 42 in different format.

Across age groups we see a consistent pattern based on the number of responses.

Responses varied based on the closeness of the relationships.

Table 43 Changes in

Relationships

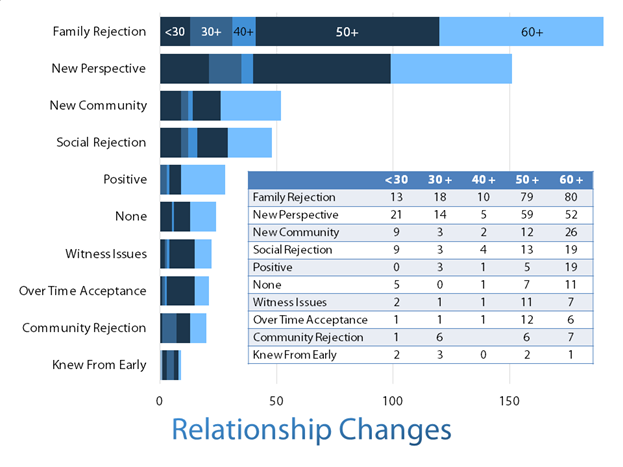

Table 44 asks for a narrative response. We see a more

significant pattern in older respondents with regard to family and orientation

to community. Respondents categorized as new perspective not only sought to

change old relationships, but make new ones. They looked at existing

relationships differently.

Table 44 Relationship

Changes

Table 45 is the same question presented in different form.

Table 45 Relationship

Changes

Conclusions

Our data addresses a wide range of complex phenomena. Our

aim is to improve critical thinking on strategies, practices, and knowledge of

the environments in which we work. We hope that this study will stimulate

conversation and new efforts to understand the attitudes and behavior of North

American Messianic Jews. Qualitative questions on peer and community pressure

are open to competing narratives. We hesitate to conclude that Messianic Jews

are either not welcome or not interested when it comes

to continuity with family and institutions or how one affects the other.

It is clear that both these forces are at work.

Through this study we explored three matters:

1.

The representation of the experiences of a group of Jews who believe in

Jesus.

2.

How this group of Jewish people experienced cultural influences during

their decision to follow Jesus

3.

How one generation’s experience compares

with another

1.

Assimilation and Communication

Our results indicate that the

Messianic Jewish community in North America is assimilated and accommodated

into 21st century culture, but has not acculturated itself.

This means that Messianic Jews see Jewish religious and

cultural forms as an important means of identification. Many want to

participate in them while still being part of the wider culture. Jewishness and

identification with the wider religious, social, and cultural characteristic

Judaism is important, but most want choice. The statistics show us that being

Jewish and identifying with Jewish values and causes is important, but so is

being part of the wider culture of choice.

We would say these results show that resources must be

brought to bear in these areas that respect a significant cross cultural

approach. This approach attempts to look at things from the point of view of

the receptors. The doctrine of sociocultural adequacy – of focusing on the

receiver’s cultural perspective – helps us appreciate the essential validity of

other peoples’ ways of life, and their basic assumptions and worldviews.

Charles Kraft is an

apologist, anthropologist and linguist. He is Professor Emeritus of

Anthropology and Intercultural Communication in the School of Intercultural

Studies at Pasadena. Kraft sees sociocultural

adequacy as an anthropological restatement of the Golden Rule; it advocates

granting the same respect and appreciation to another’s culture as we would

wish them to grant to us, were we in their place. In practicing this

anthropological Golden Rule, Kraft asserts that human well-being is a value

that transcends every culture. Thus, he affirms that we ought to look beyond

the validity of specific cultural matrices toward what we might assume those

cultural structures to be providing – genuine quality of life in material,

spiritual and interpersonal and personal areas (Kraft 1996, 509).

The majority of our

respondents are members of the “baby boom” generation. There are broad cultural

similarities, and the historical impact of this generation is ubiquitous. The

term has gained widespread popular usage. Baby boomers are associated with a

rejection or redefinition of traditional values. We associate this generation

with the birth of the modern messianic movement. We acknowledge and pay respect

to the many thousands of Messianic Jews of previous generations on whose

shoulders we stand.

David Baron was born in 1855 and cofounded the Hebrew

Christian Testimony to Israel missionary organization, in London He was a

leader in the Hebrew Christian movements of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) period in Europe. He wrote in 1893:

What we continually press upon

Jews is that we believe Jesus is the Son of Man and Son of God, not in spite

of, but because we are Jews. We believe that Jesus is the King of our people,

the sum and substance of our Scripture, the fulfiller of our law and Prophets,

the embodiment of the promises of our covenant. Our Testimony is that of Jews

to Jews.

2.

Worldview Clash and Ethnic Cohesion

Messianic Jews find truth that is consistent and coherent

with the Scripture. They do not find this same coherence in their culture.

This worldview clash is a maze of underlying presuppositions

that lie at a deep and often unseen level of thought. This worldview is a

necessary intellectual arrangement that encompasses both knowledge and

viewpoints. We assume this worldview to be true; it offers coherence and a

model of reality, and functions as a protective mechanism against other

worldviews (Hiebert, 2008, 28). Worldview serves important social and cultural

functions by providing answers to our deepest questions; it yields emotional

security, validates norms, and offers psychological reassurance (Hiebert 2008,

29-30).

The Pew study indicates that most Jewish people are attracted

to Jewishness and choice. Many are ambivalent about faith and already admit to

the existence and tolerance of competing world views. Given this ambivalence,

how do we explain this constant and consistent pressure within and without on Messianic

Jews from the Jewish community?

Ethnic cohesion is an elusive factor, perhaps made up of

some combination of pride in one's cultural heritage and a determination to

survive. Its presence often keeps a people struggling to maintain their

sociocultural existence, even in the presence of great pressure to change. The

breaking of such cohesion results in the loss of the will of a people to continue

living as a viable social entity. Tampering with this cohesion leads to, in the

language of Jewish culture, a kind of confusion. To reject the gospel is to be

accepted within this culture and, likewise, to accept the gospel is to be

rejected by the culture. We see the rejection of Jesus and the culture we

assume He represents as part of Jewish worldview and part of security, norms

and reassurance.

3.

Messianic Jews and Conventional Jewish Values

Even with the minor differences

in how the questions were framed across the various studies, these results show

that the Messianic Jewish community in North America is more similar to the

American Jewish community than to the general U.S. population in demographics

such as Jewish dispositions, education and occupation. The nomenclature

preference and religious observance levels among these Messianic Jews indicate

a continuing identification with the Jewish people. The diversity of the

Messianic Jewish community is the diversity of the larger Jewish community. We

are, in our temperaments, dispositions and activities, part of this wider

community. Messianic Jews seek ways to be part of the wider Jewish community.

4.

Hearing the Gospel

Responses to the questions about how Messianic Jews first

heard the gospel and what attracted them to the gospel underline the

significance of individual interaction. The more recent study also indicated

that churches and Messianic congregations have an emergent impact.

5.

Intermarriage

There is a need for critical thinking in the area of

intermarriage. If, as suggested by NJPS (Kosmin et al., 1991), approximately

half of the general Jewish population marries non-Jews and three fourths of

Messianic Jews marry non-Jews, how many of the children of these families will

claim Jewish identity? The intermarriage situation is dynamic. In the general Jewish community, Taglit-Birthright

Israel is altering marriage and family patterns (Saxe & Chazan, 2008; Saxe

et al., 2012). Taglit, which brings young Jews to Israel, changes the course of

participants’ deportment with regard to Jewish life. Messianic Jewish leaders

must understand who these individuals are and how they are involved with their

religious-ethnic identity. We are seeing as well, in the Messianic Jewish

community, congregations and ministries making new and dynamic efforts to

provide fellowship and service opportunities to young Messianic Jews which

alter marriage and family patterns. We see this in our intermarriage

statistics.

6.

Pressure

These qualitative results show that the older group of

messianic Jews experienced quite a bit more external pressure than younger

respondents. This older age group compromise second generation North American’s

whose immigrant grandparents and parents lived in a more secure social and

cultural dynamic.

This

survey is a snapshot of a dynamic process. Because the Messianic Jewish

community is changing so rapidly, the problem of relevant communication and

generational change develops with it. Can we measure successful communication

in less obvious and less quantifiable but equally important categories? People

are to be treated as people, not as things; they are to be respected and

consulted, not simply dominated. Potential innovations are to be politely

advocated, not rudely mandated, even when the power of the change agents is

considerable.

For us, the key is communicating Jesus as the

fulfillment of the destiny and the hope of Israel. The promise to Abraham

comes true in His person, work, and mission. What is

clear is that a new narrative of contemporary Messianic Jewish life is needed:

one that concedes the changing space, size and structure of the Messianic Jewish

community and attempts to understand how Messianic Jewish life is evolving in

the 21st century.

Andrew Barron, MA, is

the director of Jews for Jesus Canada and is presently a D Min student at

Wycliffe College University of Toronto.

Beverly Jamison, PhD, holds a BSc in Mathematics

and a PhD in Computer Science. She has served as a reviewer in mathematics,

statistics, and technology in the healthcare sector and presently works in

information technology and academic publishing.

Guttman Center of

the Israel Democracy Institute, "A Portrait of Israeli Jewry."

Jerusalem, 2000.

Hiebert, Paul. 2008.

Transforming Worldview. Grand Rapids: Baker Books.

Horowitz, B. (2000).

Connections and journeys: Assessing critical opportunities for enhancing Jewish

identity—Executive Summary. New York: UJA Federation of New York

Jews for Jesus.

Jewish Believer Survey. San Francisco: Jews for Jesus, 1983.

Kraft, Charles. 1996. Anthropology for Christian

Witness. Maryknoll: Orbis Books.

National Jewish

Population Survey 2000-01 (NJPS; Kotler- Berkowitz et al., 2004)

Pew Research,

Religion and Public Life Project. "A Portrait of Jewish Americans"

October 1, 2013.

Saxe, L., &

Chazan, B. (2008). Ten days of Birthright Israel: A journey in young adult identity.

Lebanon, NH: Brandeis University Press/ University Press of New England.

Saxe, L., Shain, M.,

Wright, G., Hecht, S., Fishman, S., & Sasson, T. (2012). Jewish Futures

Project: The impact of Taglit-Birthright Israel: 2012 Update. Waltham, MA:

Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies.

Steinhardt Social

Research Institute. American Jewish Population Estimates: 2012. Boston:

Brandeis University

United States Census

Bureau, American Fact Finder, Report DP03, "Selected Economic

Characteristics, 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates".