Churches and Missions Agencies Together

Practical Missiology and Good Practices for Partnership

Ivan Liew, Brent Lindquist, Belinda Ng, Daphne Teo, Jeffrey Lum

Published in www.GlobalMissiology.org January 2016

In October 2014, a group of 15 leaders from 4 churches and 4 missions agencies gathered to discuss the essential but thorny issue of churches and missions agency partnership in Singapore. Comprising mostly of missions pastors, agency directors, and member care specialists, this pilot working group reviewed a biblical-theological framework and model for their partnership, discussed frequently occurring issues in their relationships, and analysed case-studies that each organization had brought to the meeting. After two days, participants voiced their opinion that these conversations were the most open and transparent exchanges that had occurred between church and missions agency leaders in remembered history. We purposed to meet again, and the steering committee continued to draft strategic plans for subsequent gatherings which are simply called Churches and Missions Agencies Together (CMAT). Our atmosphere is one of joyful fellowship, mutual learning, and disciplined thinking. Our discussions are grounded in biblical-theological foundations and published research on the church-agency relationship. This process has already improved our partnership within the group, and we aim to publish a book that describes our framework in detail, and documents case studies and guidelines for good practice that others will find beneficial. Our goal is a robust practical missiology of church and missions agency partnerships in our Singapore context.

About Us

We, Churches and Missions Agencies Together, are a pilot working group of missions leaders of churches and missions organizations in Singapore who expectantly recognize that partnerships between local churches and missions agencies have immense potential to advance world evangelization. We are committed to church-agency partnerships that reflect the image of Trinitarian relationships, incubate effective missions practice, and nurture optimal missionary care. At the same time, we admit that the effective practice of such inter-organizational relationships are unfortunately rare. We know that our own partnership practice falls short, thus we seek to learn and work together within an environment of relational trust and transparency.

Our Values

We affirm four values of church-agency relationships that undergird our partnership practice. These values form the basis of the Relational Model for Church-Agency Partnerships that further describe our partnership practice: (1) Biblical centrality of the church, (2) Equal value of church and agency in missions, (3) Mutual deference and glad submission, and (4) Joyful fellowship and encouragement. We now present the biblical and theological basis for these values. Note that the final paragraph under each value, contains an explanation that summarizes the biblical basis and may serve as a standalone summary description.

1. Biblical Centrality of the Church

Christ established his ἐκκλησία (Mt 16:18), which from New Testament times, has always had its expression as a local gathering of believers who adhered to the creed “Jesus is Lord” (1 Cor 12:3; Rom 10:9). When Jesus commissioned his eleven remaining disciples to “go and make disciples of all nations”, this command was therefore given to a localized group of his ἐκκλησία. When God called Paul and Barnabas to missionary work, the Holy Spirit spoke to the church in Antioch who commissioned and sent forth this missionary band (Acts 13:2-3). Thus, the local church was established first and missionary bands, the functional precursor to missions agencies, were subsequently called out from the church.

We affirm the biblical centrality of the local church, and the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization’s statement that for parachurch organizations, “independence of the church is bad, co-operation with the church is better, service as an arm of the church is best.” The mandate of global missions was given first to the local church and subsequently to the missionary band. While the global Church is entrusted with the call to missions, the responsibility and ownership of missions rests primarily with the church and subsequently to the missions agency.

2. Equal Value of Church and Agency in Missions

While the church is given the first responsibility and ownership for global missions, missions agencies have a strong biblical and historical evidence for their existence and effectiveness. When Paul and Barnabas were sent by the church in Antioch (Acts 13:2-3), they functioned as an autonomous group while still consulting and involving the Antiochean church for major decisions and subsequent ministry (Acts 15:2, 22). Throughout church history, specialist groups such as missions societies, monastic orders, and the New Testament missionary bands have had much greater impact on world evangelization than local churches or denominations. In post-Reformation times, the missions agency has similarly proved far more effective than the local church in missionary endeavours to unreached and least reached peoples.

This tension between the biblical centrality of the church and the greater effectiveness of the missions agency, evidenced historically and in Scripture through missionary bands, can be addressed by a Trinitarian model for partnership. Relationships between the Father, Son and Holy Spirit simultaneously evidences differing roles and the equal value of distinct persons within the Godhead (Jn 5:18, 8:19). Since we are created in the image of God, the Trinitarian perichoresis provides us the divine blueprint for our inter-personal and inter-organizational relationships.

We affirm the equal value of church and agency in cross-cultural missions. In partnership, the church and missions agency should equally value one another, esteeming each other in mutual interdependence in the joint missions endeavour.

3. Glad Submission and Mutual Deference

Within the Trinity, equal value of one another perfectly co-exists with the differing roles of each person in the Godhead. Jesus gladly submits to the will of the Father who has given him a mission to complete (Mt 20:23; Lk 22:42; Jn 6:38). Jesus is able to accomplish this mission because the Father has deferred authority to the Son (Jn 10:17-18). This intertwining ministry extends to the Holy Spirit in John 16. Jesus ends his earthly ministry so that the Spirit begins his ministry (v.7). Christ defers to the Holy Spirit who accomplishes his work of continuing the ministry of the Son and glorifying him (vv.14-15), so the deference is mutual and the submission is glad.

The church has biblical centrality, and therefore the primary responsibility and ownership for missions, but the church will choose to defer authority over certain matters to the missionary band and missions agency (Acts 13). Deference in this manner flows out from the church esteeming the missions agency with equal value in missions. In turn, the missions agency serves the church in its missions involvement, including the sending of missionaries. Such is the expression of glad submission and biblical centrality of the church.

We affirm that glad submission and mutual deference will characterize our conduct and communication amidst the many decisions that will be made within our church and missions agency partnership.

4. Joyful Fellowship and Encouragement

Not only does the Trinitarian perichoresis provide us the divine design for relationship, Christ draws us into the triune relationship to participate in this joyful fellowship. We are invited to experience unparalleled love and unity, with the Father, Son, Holy Spirit, and one another, so that the world may believe that Jesus is Lord (Jn 17:20-26). Thus, we are created in the image of God to experience the joy of fellowship inseparable from the work of missions.

Such practice of joyful fellowship and encouragement has not always been realized, whether in present times or the first century. However, Paul presents this as the biblically preferred model in his relationship as a missionary with the churches he planted, and those that supported him. The Ephesian church evidenced this close fellowship with Paul (Acts 20:36-38). Paul thanks the Philippians for their κοινωνία in the gospel (Php 1:5), often translated as partnership, sharing, and participation in the gospel. The pervasive sense of mutual relationship and encouragement throughout the Philippian epistle, together with Christ’s prayer for inclusion in the joyful Trinitarian relationship of love (Jn 17:20-26) form the biblical basis for joyful fellowship and encouragement in the church-agency relationship.

We affirm that joyful fellowship and encouragement between the church and missions agency is the biblical norm for our partnership relationship. This relational expression of unity in the body of Christ is crucially embodied in the personal relationship forged between our church and missions agency leaders, for their relationship sets the tone for the inter-organizational partnership.

The Relational Model of Church-Agency Partnerships

The Relational Model of Church-Agency Partnerships (REMCAP, see Figure 1) was initially developed from doctoral research conducted by Ivan Liew, and subsequently improved with further interaction among a widening circle missions leaders. The original research consisted of a case study of the partnerships formed between Woodlands Evangelical Free Church and three missions agencies in Singapore. Interviews and focus groups were conducted with agency directors and missionaries sent from the church through these agencies, and findings were distilled into the model. Subsequent application and improvements were made by CMAT, our pilot working group of missions leaders from churches and missions agencies.

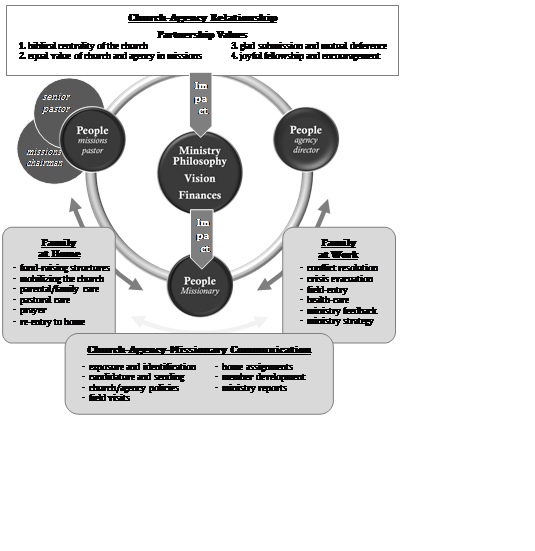

This model encapsulates the five primary concepts of people, relationships, ministry philosophy, vision, and finances that constitute the practice of church-agency partnerships, and describes their relationship to missionary mobilization and member care. The quality of the partnering relationship between missions pastor and agency director impacts how ministry philosophy, vision, and finances are viewed between the organizations. In turn, how these primary concepts are exercised impacts the mobilization and member care experience of the missionary. The biblical-theological framework of this model consists of four values: (1) biblical centrality of the church, (2) equal value of church and agency in missions, (3) glad submission and mutual deference, and (4) joyful fellowship and encouragement.

Good practice of the primary concepts of partnership includes both the church and the agency being involved in the missionary’s life and ministry. Certain areas in mobilization and member care are most effective when addressed by the church, while others are most valued by the missionary when they are addressed by the missions agency. The distinction between these can be summarized as family at home, family at work. Some areas of mobilization and member care stretch across this distinction and are best practiced by church and agency together, necessitating effective inter-organizational communication. All these findings are depicted in the model, which may serve as a guide for improving church-agency partnership practice. The Relational Model of Church-Agency Partnerships provides needed clarity for church-agency partnerships, guides how partnership relationships can best be strengthened, and grounds the strategy in both researched data and values based on Trinitarian theology.

Pilot Working Group

Our pilot working group, Churches and Agencies Together, purposes to:

1. Improve our own church-agency partnership practice with the participants of our working group. Current and past issues will be analysed with transparency and willingness to learn and hear advice and hurt from others. Our environment will be one of joyful fellowship and encouragement as we seek to apply our biblical-theological values to issues brought to the table.

2. Apply, critique, and further improve the Relational Model of Church-Agency Partnerships as a framework that informs our practice as a sound yet simple model of optimal church-agency-missionary relationships.

3. Develop written guidelines for good practice for church-agency partnership. Formed with greater detail than our values and relational model, these guidelines will reflect the consensus of both church and agency leaders. Documentation of our working process will take place with academic rigour, attempting robust practical missiology in our Singapore context.

4. Benefit other churches, missions agencies, and missions networks in Singapore and beyond. In this spirit we openly share information and welcome critique of our research process, analysis and results.

In using the term “pilot working group”, we indicate that we are not a permanent fixture nor an organization seeking to grow. We seek to foster understanding and clarity in partnership between churches and missions agencies, thus contributing to other organizations, not being an organization ourselves. We do not meet primarily for fellowship, though joyful fellowship is a theological basis for our gathering. We do not meet for seminars, but to each contribute in a learning and working environment. We do not meet for theoretical development, because current partnerships are being practiced within the group.

The Steering Committee within this group plans for leaders to meet for one full day, every 3 months over one year to discuss practice, share results, document our process, and nurture joyful fellowship and encouragement in missions. Each meeting will involve active contribution from participants such as case studies and reviewing jointly crafted documents. Participants bring real life church-agency partnership problems and to work on and good examples to share.

Members and Steering Committee

Churches and Agencies Together is guided by a steering committee led by Ivan Liew (Woodlands Evangelical Free Church) with the following members: Jeffrey Lum (Bartley Christian Church), Belinda Ng (SIM, Serving in Mission), and Daphne Teo (OMF, Overseas Missionary Fellowship). Brent Lindquist (President, Link Care Center, USA) serves as a consultant to the working group.

Table 1. Participants of Pilot Working Group

|

Churches |

Leaders |

|

Adam

Road |

Ler Wee Meng Lim Luck Yong |

|

Agape

|

Thomas Lim |

|

Bartley

|

Alvin Tan Jeffrey Lum* Serene Lum |

|

Woodlands Evangelical Free Church |

Ivan Liew* |

|

Missions Agencies |

Leaders |

|

OMF Singapore |

Daniel Wong Daphne Teo* Paul Tan |

|

Pioneers inAsia |

Mark Syn |

|

Serving in Mission |

Belinda Ng* Kelvin Chen Leonard Leow |

|

X-Pact |

§ Joshua Ramachandran |

|

Consultant |

|

|

Link Care Center |

Brent Lindquist* |

* steering committee members

As we are a pilot working group, we seek to build trust and transparency, aiming for a depth of interaction that precludes us growing into a large group. However, should other church and missions agency leaders wish to enter into a similar practice, applying the church-agency partnership values we are developing, then the steering committee members will gladly assist. The formation and collaboration of additional groups, with more churches and missions agencies involved, will further strengthen the model and jointly developed good practice guidelines.

Case Studies

A key method of achieving our purpose and generating our products, is exploring case studies in our pilot working group. Members write case studies and bring these to the group for discussion according to the following guidelines.

1. First, the purpose of the case study is to explore application of our four values and the REMCAP model to actual church-agency partnership practice. The purpose is achieved when exploration culminates in good practice guidelines that are documented and agreed upon by members of the pilot working group that represents a range of churches and missions agencies.

2.

Second,

the topic of the case study could be an actual incident or a composite of

factual incidents and situations. The case study should not identify particular

individuals, but may identify organizations within the pilot working group when

permission of the representative of that organization is granted. Discussing

real situations, with representatives of those organizations present, brings

great depth and authenticity to the application of values and writing of good

practice guidelines.

3. Third, the case study should be brief, comprising of 100-250 words. This length includes 2-4 specific questions at the end of the case study that direct the ensuing discussion. The questions should highlight the specific topic at hand and draw out good practice guidelines that the group seeks to agree upon.

As participants brought case studies to the pilot work group, we engaged in transparent discussion. Some cases were written from either distinctly church perspectives, or distinctively missions agency perspective. The challenges were discussed with openness in light of our shared values and the Relational Model of Church-Agency Partnerships, and summaries of conclusions were documented. The following are samples of actual ministry case studies that illustrate joint analysis by both church and missions agency leaders, and mutually agreed upon good practice guidelines.

Case

Study 1:

Church Involvement in Field Conflict

Andy and Evelyn were experienced missionaries serving in Japan in a multinational team of a missions agency. Inter-personal conflict and differences in ministry strategy arose within the team. Field leadership was aware and various interventions and counselling sessions took place, but the conflict was not fully resolved over several years. Andy and Evelyn’s sending church believed that it should not generally interfere in field matters, so church leaders at first restricted their role to encouragement and pastoral care. After 2-3 years however, the church leaders felt that their missionary was not being fairly dealt with and was concerned for their emotional health. The church leaders shared their concerns with the agency director with whom they had a good relationship, indicating that if significant changes could not be made for their missionary within the agency, they would remove their missionary out from the agency even though they did not want to do so.

1. When should the church "step in" to field matters, if at all?

2. How should the agency involve the church when missionaries are involved in a field conflict?

Group Analysis

Interpersonal conflict is always multi-faceted with each person having a role and part to play in the dispute. In such scenarios, dialogue should be tripartite at an early stage involving church, agency, and missionary. If the church does not engage the agency, but only hears from the missionary then a one-sided view will emerge. While the sending church is right to have a strong interest in the well-being of their people, even with the best of intentions they may not have the whole picture, so a joint decision is always best. The solution is never so simple as removing the missionary and solving the problem.

Should the church ever step in to field matters? The group concurred that yes, after an appropriate time. Stepping in too soon will cause more damage and be seen as inappropriate interference. For the agency, wisdom is needed also when to involve the church. Alerting the church for every problem is foolish, but the agency should also not delay communicating to the church until the problem becomes so serious that there is no choice but to communicate! By this time, the church would likely know that a problem exists and become frustrated that they have not been involved.

In this particular case, there existed joint agreement between church and agency that enough time had been given to attempt to resolve the conflict. Effort had been invested by all parties over a period of years, not months. While the church eventually approached the agency saying that they wanted significant changes to occur, this happened only after numerous discussions over a long period of time that involved church, agency, and missionary. An important fact was that the missionary also wanted significant change. When the church approached the agency, making their feelings and position known, it was a risk in the relationship for they did not know how the agency would respond. In the end, the director of the agency agreed with much of the church’s concerns. Within the agency there existed differing assessment of the conflict and the missionary in this case study. The agency director concurred with the church and took appropriate action. As a result, the missionary changed teams and is doing well in ministry. The church-agency relationship became stronger.

The agency director emphasized the importance of a pre-existing tripartite relationship. In this case, church, agency and missionary all knew and trusted each other well. The director shared, “Be slow to take sides. It doesn’t mean that everyone in my organization is right. Our ultimate allegiance is to the Lord not to my organization.”

Consultant Response

This case illustrates a common scenario with an uncommon ending, that is, things worked out very well. While this is not unique to Singapore, it does illustrate the strength that can come from tripartite relationships because of the closeness of the Singaporean context. It may not be easy to develop this closeness in the larger countries, but this would still be a worthy goal.

One concern that arises out of this is the long time it took for everyone to try to solve the problem. Is this an Asian distinctive of not wanting to confront? It could be, but the presence of a document that clearly outlines the process of working through difficulties would no doubt be of benefit in any culture. Knowing what to do would be of great help regardless of one’s perspective on behaviour in conflict. Knowing what to do, when, is a second issue. Let’s look at the first: Knowing what to do.

As it becomes apparent that there are problems on the field between a missionary and the team, it is important to look at the causal factors. They could include primarily work or personal issues (like personality traits) separately, or a mix of the two (most likely). Also, there could be issues with the local context, whether it be cultural or with the local believers.

The question becomes, what are some of those kinds of issues? Each mission or church (or this pilot project work group) could develop a general list of situations. These would form the introductory part of the working document, which would serve as an alert on all parties that something was going on. And, each party is allowed to surface the presence of the issue.

Once the question has been asked (in the case of the missionary on the field, this would be the purview of the agency to investigate) the agency would determine whether an issue needed to be addressed. And then, to be simplistic, it would, and an action plan would be developed, and applied, with appropriate timelines for review.

In this scenario, the “when,” question sort of takes care of itself. The primary question is, “Is there a problem?” And then if the answer is affirmative, the “when” becomes “now.”

In summary, in order to address this case study example, the mission and church need to endorse a set of situations that they would forecast might be problematic in the lives of the missionary, and agree that all could ask the question. This list would not be hard to craft, with the understanding that it could be added to as necessary.

Case

Study 2:

Aftermath of Crisis Evacuation

A natural disaster swept through the Philippines causing widespread destruction. Relief efforts were underway, but a disease outbreak threatened further loss of life to everyone involved, including the missionaries. Multiple agencies and churches had missionaries on this field, all with varying concerns.

One particular sending church had several missionaries on this mission field. They had their own deliberations and decided to recall all their missionaries from the field, citing concerns for their safety. They came to this decision unilaterally, without consultation from the field or the missions agency director. The church communicated this decision to the missionaries and agency director, and gave instructions for their missionaries to return home.

1. How should communication between missionary, agency and sending church be improved in a crisis situation so that mutual understanding is increased and consensus is reached?

2. Who should make the final decision regarding crisis evacuation of missionaries?

Group Analysis

The need for church, agency and missionary to deal with crisis situations is becoming increasingly common, whether the crisis is political, an act of terrorism, a natural disaster, or a disease epidemic. In such situations, it is crucial that the final decision involves all parties. The feeling of one party that a decision is unilateral is a key indicator that such actions damage relationships, leaving people feeling unhappy and hindering future ministry.

Biblical centrality of the church never means that unilateral decisions should be made. The church must be involved, but should defer to the missionary and the missions agency because local information near to the source is the most valuable. News reports received via TV and the Internet at home often results in the sending church feel that the crisis is critical, when the missionary himself knows that the bomb blast was in another city and is not affecting him. The church therefore defers to those with local knowledge in the field. The ultimate decision on whether to evacuate or not may lie with the area leader, country leader, or team leader depending on the structures of each missions agency.

The missions agency should keep in mind however, that the church often faces pressure from family members and the congregation who are worried about their missionary. The church may want to bring the missionary home believing that is the best choice for member care. Leadership may feel that prudence is the best option because they would bear the fallout if anything negative happened and they could have prevented it.

The role of the missionary and how he or she facilitates this process is critical. They are simultaneously communicating with family, church and agency leaders. The missionary should wisely manage the communication, in particular the feelings of family and church who are geographically removed from the crisis and may be thinking the worst.

Local partners themselves are often not only a valuable source of information but invaluable in consultation. Often we think that local believers will feel abandoned if foreign missionaries evacuate. This may be the case, for there are reports that ministry has had breakthroughs when missionaries stay amidst crisis. On the other hand, examples were shared when locals were consulted and they said to the missionary, “You should leave now while you can. You are in more danger than us, and if you stay you put us at greater risk!”

We should make extra efforts to communicate in times of crisis and when decisions are made. In a related case, a member of the group shared how a team initially decided to stay. Later however, one country’s embassy advised their citizens to leave the country. A missionary of that country in the team consulted her leader who gave his blessing that she leave, which she did. However, when the crisis was over and she wanted to return, the church questioned her decision to leave and now return! In the end, she never returned to the field. Though the missionary’s decision to return home was endorsed by the agency and her team leader, the church was not sufficiently kept informed resulting in subsequent damage. This particular missionary was new to the field, so it was understandable that she was feeling unsafe with many transitions to undergo. In times of crisis, we must allow some people to reach different conclusions, including different individuals in the same team or different churches sending through the same missions agency. In all these however, extra effort spent communicating among church, agency and missionary is never wasted.

Consultant Response

The response to this case is excellent. It would seem to be of strategic value that extensive preplanning be done with the church and agency about how crises are understood, and in the case of terrorism or political events, who the outside references are going to be the thought leaders. For instance, for US agencies, the State Department or Homeland Security entities may become the reference points in determining evacuation.

Also, the agency needs to have evacuation models ready to implement that may include restrictions in daily activities, and differing levels of evacuation preparedness. Also, for each emergency, there needs to be clear and continuous contact with a safety team, which the agency may manage, but which the church can access easily. Certainly, family anxieties may compound and cloud decision making in difficult times, which means that therefore a way to reinstitute a plan after the original fell apart may be necessary.

In this example, a church may agree beforehand to consult with the mission, and then go ahead and unilaterally act and bring its missionaries home. Realizing this may happen, means that there is a “plan B” to help care for the missionaries no matter how they evacuated. We need to avoid finger pointing and such and focus on caring for people.

Case Study 3: Preparations and Expectations for Short-Term Missions

Janet was a single missionary sent for 1 year short-term missions. Her church wanted to send her through a missions agency, but they requested that she not attend the agency’s recommended pre-field training because she was only going for one year. During her time on the field, her church expected her to host multiple short-term teams. Though the agency felt that she had insufficient competence in the local language and culture for these expectations, and omitting pre-field training was against their guidelines, the agency agreed to these requests. Her team leader on the field readily accepted her placement on the basis of her sensing God’s call, a prior one week missions trip on that field, and the sending support from her church and missions agency.

Soon after arriving on field Janet applied for a long term visa. This required medical tests and criminal record clearance, which added to her stress levels. After 3 months on the field, she abruptly returned to Singapore. The reason for the sudden return appears to be medical in nature, however she has refused to talk to anyone and has cut herself off from the church. Her pre-field psychological assessment was clear, but in hindsight, some comments made by referees may have been brushed off due to exigency of the need. Church leaders are upset over her premature return, and church and agency leaders are divided in their assessment of Janet’s case.

1. What key lessons can be learned for sending short-term missionaries from this case?

2. When church and agency policies differ regarding the sending of a missionary, how can the variance be best resolved?

Group Analysis

Due to the fact that the field was keen to receive the short-termer, and the church was keen to send, Janet was sent with agency policy regarding pre-field training was not followed. In this case, the missions agency did not have a fixed policy but a preferred recommendation for their pre-field training before one year of missions service. All parties, church, agency and missionary in this case were less stringent on pre-field preparation because this was missions service was only for one year.

CMAT agreed that pre-field cross-cultural preparation for short-term missionaries going for 6-12 months on the field should be similar to a career missionary’s preparation, because the adjustments that both missionary’s face are comparable. However, for a shorter missions service of 1-3 months however, the end is near in sight, so should there be any negative experiences the missionary is likely to be able to bear with them for 3 months, resulting in their return not feeling like a failure.

The agency was trying to be accommodating to the church, and also concessions regarding the church’s expectations for Janet to host missions teams. They had not yet built strong relationships with the church leaders, so did not emphasize their concerns. The CMAT group agreed that any short-term service of a year should be treated primarily as a learning experience for future ministry. In particular, the church and the missionary himself may have hopes of certain results achieved in that year. Crucially, we must identify unrealistic expectations in light of the field realities and the capacity of each person. In this case, the difficulty of the field context was underestimated. While certain fields may be more familiar to a new missionary other fields require more difficult cross-cultural adjustments. If missionaries are undergoing their own cross-cultural adjustments, having them host teams is not generally recommended.

The CMAT working group noted their experience that when a missionary is rushed through the sending process, by either the church or the missions agency, problems frequently occurred, that could have been better addressed at the time of sending. In Janet’s case, she could have been better prepared, external stress factors could have been mitigated, and personal issues could have been explored further.

Though Janet’s psychological assessment did not raise red flags, the CMAT working group noted that these assessments are not fool-proof “magic reports” because people may disguise problems, either intentionally or unintentionally. The church and agency should highlight possible concerns to the psychologist conducting the assessment to see if these can be validated, rather than expect the psychological assessment to discover unknown problems. For example, concerns of referees, though not major, could have been surfaced to the psychologist conducting the assessment.

Church and agency leaders must be particularly mindful when relationships are not strong before a critical decision is made, whether sending a short-term missionary or otherwise. Particularly in these times, we must not push the desires of one party, but take time to respect, and at times demonstrate mutual deference to the processes and policies of each organization. In this case, the agency did not want to damage relationships with the church and allowed their recommendations to be overlooked, however the end result was that relationships were made even worse - the church leaders were upset with the missions agency and the assigned mentor for allowing this to happen and not foreseeing the problems. Increased dialogue between church and agency, guided by the REMCAP framework would have helped this case. For example, REMCAP shows that field entry preparation is most valued coming from the agency, thus with the value of glad submission and mutual deference, the church could have deferred to the agency’s policy for pre-field training for Janet’s sending, and the agency would not have felt that it must acquiesce to the church for the sake of the relationship.

Consultant Response

When we rush through things, something often happens which usually isn’t good! There are many mistakes in this case study where issues were forced through: a naïve missionary, with everyone hoping for the best was just the beginning. Should anything like this ever be attempted? Possibly yes, but only if a strong and mutually agreed upon safety net of oversight and communication is developed. A working document of relationship, which includes length of service with preparation needs, expectations, and requirements, would soften problems when they arose, even if the leaders change.

Publishing Good Practice Guidelines

The fruit of CMAT’s close collaboration is not only the improved relationships and practice of partnership within the group, but the goal of a tangible product. The working group is in process of jointly publishing a book called Churches and Missions Agencies Together – Volume 1: Foundations of Relationship. The book will be authored by all members of the CMAT pilot working group. This article is a foretaste of this future publication.

The first part of the book will present a framework for church-agency partnerships. The current state of church-agency partnerships will be described, and the biblical-theological framework will be presented. The research that formed the theoretical basis of this work, together with the REMCAP model will be expounded upon. This book will be the first known attempt to not only publish a model that describes the constitutive workings of the partnership between church and missions agency, but one that is based on published research, and validated by a working group of church and missions agency leaders who are using it in practice.

The second part of the book will present good practice guidelines (proposals) written by various members of the CMAT working group. These guidelines have been agreed upon in consensus, and formed through application of our values and the REMCAP model to the real-world case studies discussed in the working group. The case studies will be documented for the reader, and are a significant part of this practical section of the book.

The third and final part of the book will be brief but an important agent to catalyse positive change. This section will seek to guide the reader in applying the lessons we have learned and documented in the book. It will present the necessary tools for others to start a CMAT group within their own network of churches and missions agencies, and how to use their own case studies to improve partnership practice. The original CMAT pilot working group members may also branch out to facilitate or consult with new groups. Extending further, some groups may feel able to work closely with the CMAT Steering Committee to document additional case studies and write the second volume of Churches and Missions Agencies Together.

Concluding Remarks

This article has described the close collaboration of a pilot working group of missions agency and church leaders. This group is comprised of leaders who believe in the importance of church-agency partnership in the missionary endeavour, and who admit that we can learn much from one another to improve our practice. The pilot working group, called Churches and Missions Agencies Together (CMAT), has united around a common set of values that are based on a biblical and theological framework for church-agency partners. These values, and a Relational Model of Church-Agency Partnership were developed from published peer-reviewed doctoral research conducted in the context of Singapore. Case studies have been presented in this article, as a foretaste of a future book that we seek to publish that will document good practice guidelines for partnerships between churches and missions agencies.

This article and the work described therein is an initiative of the Steering Committee of Churches and Missions Agencies Together. For further information please contact:

Rev Dr Ivan Liew

Missions Pastor

Woodlands Evangelical Free Church

www.wefc.org.sg

iliew@wefc.org.sg

|

Figure 1. The Relational Model of Church-Agency Partnerships