SERVING CHINA’S INTERNAL DIASPORA:

MOTIVE, MEANS AND METHODS

Enoch Wan & Joe Dow

Published in Global Missiology, January 2016 @ www.globalmissiology.org

I. Introduction

1.1 Purpose and approach

This paper is different from earlier publications, because it is neither general in scope on Chinese diaspora[1] nor on urban centers in the US;[2] but on internal diaspora in China’s urban centers. The purposes of this paper are: first to analyze some of the issues facing China’s internal diaspora then to consider possible responses from the church.

This paper will be largely reflective in nature, offering observations from Enoch Wan’s decades-long teaching/training ministries among China’s internal diaspora and Joe Dow’s eight years of personal experience and close friendship with China’s migrants. Each section will include “case studies” in the form of personal stories that illustrate both the migrants’ plight and ministry potential among them. In addition, we will look to the Gospel of Matthew to shed light on Christ’s heart and the church’s duty. To make it more readable and personal, the term “I” is used whenever personal stories are told.

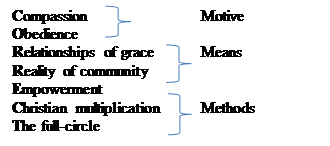

In terms of serving China’s internal diaspora, we will approach the subject matter utilizing Enoch Wan’s “CORRECT” approach (Wan 2003)[3] to consider various aspects of the church’s possible response within the three broader categories of motive, means and methods.

FIGURE 1 – “CORRECT” APPROACH SERVING DIASPORA

|

1.2 Definition of key terms

For the sake of clarity, two key terms are defined below :

· Case study – an in-depth study of a chosen phenomenon, project, program…etc. in

real life situation.[4]

· China’s internal diaspora – Chinese migrants being away from homeland residing

elsewhere within China.

II. BACKGROUND OF CHINA’S INTERNAL DIASPORA[5]

In 2010, for the first time in history, China’s urban population surpassed that of its rural counterpart. It is expected that the historical rural/ urban divide of 80% and 20% respectively will be reversed by the year 2030, all in line with the central government’s aggressive urbanization strategy. The unprecedented demographic shift and rapid urbanization in China have been accompanied by deep social pressures, dividing millions of families across the nation and depriving an untold number of people of adequate education and health care.

At the outset, it is helpful to understand the political and social background of today’s migrants. In 1958, Mao Zedong instituted the system of family registration (hukou) as a means of tracking all of China’s citizens and to prevent villagers from migrating to the cities. All social services such as medical care and education were tied to the hukou; the sick would be treated and children would receive an education in their hometowns, the place in which they were registered. When the economic reform era began in 1979 under Deng Xiaoping, foreign-owned factories and industries sprang up by the thousands, all requiring cheap labor for building, manufacturing and maintaining. Uneducated villagers began pouring into coastal areas, finding employment as unskilled laborers on construction sites and in factory assembly lines, and as security guards and cleaners, trash recyclers and fruit sellers.

Throughout the 1980’s the initial waves of migrants transformed – seemingly overnight – coastal towns into megacities, and further swelled the population of already large cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan and Guangzhou. Just 30 years later, 300 million villagers had left their homes in search of a piece of China’s growing economic pie, and fueling the engine of the world’s hottest economy.

The price paid by the migrants, however, has been steep. For one, China has yet to change the outdated hukou system[6](in spite of many voices calling for its abolition), leaving migrant families without access to education and medical care. Many families feel forced to separate, and it is not uncommon for a family of three (two parents and a child) to all be living apart from one another, with both parents working in different cities and the child being cared for by relatives in the hometown. Furthermore, though education in the villages is improving, it is still common for youth to drop out of school at a young age to travel to the cities for work, receiving little guidance from parents and having poor prospects for marriage. The villages themselves have been decimated with only the elderly and the children left behind in many of them. In addition, as the villagers and urbanites now live side-by-side in the cities, most migrants can describe their experience of being discriminated against by wealthier and more sophisticated neighbors. There are also countless stories of migrants working on the basis of a verbal contract but not receiving promised wages, and then finding no legal recourse.

Yet, in spite of all these hardships, they continue to come to the large cities, driven by the hope of a more prosperous life and a better future. It is unknown how long the “migrant phenomenon” will persist. Already there is a national strategy to encourage industry in lower tiered cities so that more migrants can find work closer to their hometowns. However, the process of “settling China” is expected to take many more years; therefore, the needs of the migrant community and potential ministry opportunities will persist for some time.

III. MOTIVE OF SERVING CHINA’S INTERNAL DIASPORA: COMPASSION AND OBEDIENCE

In Matthew’s Gospel, as Jesus prepares his disciples for that final commission (28:18-20) he trains them in the way of compassion. Following his introduction (1:1 – 4:16) and the call of his first disciples (4:17-22), Matthew sandwiches Jesus’ discipleship training process around his concern for the crowds.

Caring for the crowds (4:23-25)

Discipleship Training, part 1: Sermon on the Mount (5-7)

Discipleship training part 2: Ten miracles (8-9)

Caring for the crowds (9:35-38)

His own motivation is expressed at the end of this section in 9:36: “When he saw the crowds, he had compassion on them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.” This verse describes what Jesus saw, felt and knew about the crowds. His sense of compassion (what he felt) stemmed from seeing the crowds and knowing their plight.

To share the compassion of Christ requires that the disciple sees what he sees and knows what he knows. Through chapters 8 and 9, Jesus heals people by either speaking to them or touching them, bringing him into close proximity with the individuals who made up the crowd. In these individuals he discovered a myriad of needs, enabling him to see that they truly were “harassed” (literally, skinned alive) and “helpless” (literally, thrown down), vulnerable sheep in a hostile world. One of the first descriptions of Jesus is taken from Micah 5:2 (see Matthew 2:6): “…a ruler who will shepherd my people Israel.” By the end of the ninth chapter of Matthew’s narrative we see this shepherd heart expressed after he considers the enormity of need situated within the crowd. To share Christ’s compassion requires that the disciples actually engage with the poor, but the chasm is wide between city Christians and migrants, and crossing it has proven to be difficult.

China’s urban churches differ from migrant churches, the former mostly comprised of middle class, educated Christians with greater earning potential and the latter poorer, uneducated and generally reflecting village culture. Though they possess resources to meet the needs of the urban poor, it is rare to find Christians in city churches engaged in meaningful relationships with migrants. The four obstacles to bridging this divide are political, social, cultural and theological. First, since 1949 all Chinese have been raised in the political reality of a supposedly socialist nation, and were offered the vision of Mao’s “iron rice bowl,” an assurance that the state would take care of them. Though China become an essentially capitalist nation with a wealth gap rivalling that of the United States, most of its citizens, including wealthy Christians, still believe it is the government’s job to meet the needs of the poor. Second, the social obstacle is found in the traditional understanding of family; historically Chinese are responsible to help family but feel little responsibility for the needs of strangers. Third, there is a wide cultural chasm between the city and the village. Urban Christians have told me that it is easier for them to relate to people from other countries than to villagers from within their own country. Finally, there has been a “hole in the gospel” that has proclaimed in China over the past few decades, a gospel that so emphasizes the importance of the soul but to the point of saying next to nothing about Christ’s concern for physical needs. The theological obstacle faced by city churches nurtured by such a gospel is that they simply have no compelling, theological reason to reach out to and embrace poor strangers. As Christians who inhabit the kingdom of God, we must first tackle the theological obstacle, and teach about God’s concern for the whole person.

For this reason, the spiritual formation of city Christians must include being nurtured in the compassion of Christ by entering the world of migrant workers. In my own experience, it has been through friendship with these people from a very different cultural background, I have personally grown in sharing the compassion of Christ. In Beijing, I lived in quite a luxurious apartment, compliments of friends from Hong Kong. Most of the other residents were wealthy business people who drove high-end cars, but the security guards were all young men from the countryside, most in their early 20’s. They were paid less than minimum wage, and even this was often withheld at the whim of the management company who would regularly cite certain, quite minor infractions. They were housed in a dormitory space next to the underground parking: two concrete, dank and windowless rooms for about 12 of them.

One of the guards was the 25-year-old Guohong from a village in the neighboring province of Hebei. His wife and young son lived back in his hometown, and Guohong would send most of his monthly wages back to them, though he often complained that his wife was spending the money faster than he was earning it. We spent a few years developing our friendship; I would visit them him and the other guards in their dormitory and Guohong would occasionally come to my flat. Though we would both eventually leave Beijing we have kept in touch over the years, and always addresses me as “older brother.” He has traveled around, working on construction sites in different provinces, in Inner Mongolia, Fujian and Jiangsu, usually staying for a year or two in each place, and continuing to send most of his earnings to his wife. Two years ago, however, he discovered that she had been having a long-term affair, and had been using his earnings to support the other man. Guohong is now divorced, and his son is being cared for by his parents. Now a single man, he continues to work in construction, currently near Nanjing, and sees his son once a year. Guohong is one of 300 million who make up the “migrant crowd,” each of whom has a story to tell.

Another young friend is Xiao Fan from the province of Henan, who set up a small noodle shop close to my home in Beijing. We became close friends, first as a customer in his shop and especially when I helped mediate a dispute one night between him and his 18-year-old kitchen assistant. At 30 years of age and single, Xiao Fan was earning enough just to support himself and to send a little back to his retired parents in the village. Three years ago he closed his shop in Beijing and moved to Nanjing for two years where he opened another noodle shop. A year ago, he closed that shop and returned to Beijing where he has opened yet another noodle shop. Xiao Fan is now in his mid-thirties and is haunted by the fact that he has no marriage prospects, and very little to offer a potential wife. He is like millions of migrant young men, desperately trying to find enough economic success to make him “marriageable,” but all the while watching his youth slip away.

My friendships with people like Guohong and Xiao Fan has allowed me to enter the world of migrants, and has served to nurture me with compassion of Christ. By entering their worlds, I have been given an opportunity to “see and know” in the way of Christ, to witness first-hand the pressures that they face, and have thus become more acutely aware of these vulnerable sheep who need a shepherd. How can we bridge the relational chasm between wealthy urban Christians and migrants? How can we help disciples of Christ in the city to see and know the plight of their rural counterparts, so that they can learn the compassion of Christ?

Over the years we have endeavored to introduce people across socio-economic boundaries. The two aspects of motive – compassion and obedience – are related in a catch-22 kind of way, and it is difficult to place a chronological priority on either. In order to experience Christ’s compassion, we must “cross the street” in obedience to him, and making the choice of getting to know our neighbor. This initial obedience is the first step towards gaining the compassion that will be the inspiration and fuel for persevering in further obedience.

IV. MEANS OF SERVING CHINA’S INTERNAL DIASPORA: RELATIONS OF GRACE AND REALITY OF COMMUNITY

In Matthew’s Gospel, the Gentile plays a significant role. To the first century Jew, the Gentile was an outsider, and traditional and faithful Jews would not have considered sharing a meal with them or visiting a Gentile home. As Jesus prepares his Jewish disciples for the climactic commission of actually going to the Gentiles (Matthew 28:18-20), he has to en-culturate[7] them in the ways of the kingdom of heaven, a place in which all “outsiders” are welcome. In the first few verses of Matthew’s Gospel, four Gentile women are found in Israel’s royal genealogy, entering the Gospel story abruptly and without apology. The first characters to identify Jesus as King were a group of Gentile sages (2:1-10) and the first to acknowledge that he was the Son of God after his death on the cross was a Roman centurion (27:54). Whereas he chastises his closest disciples for their small faith (8:26; 14:31), the only ones he declares to have “great faith” are a couple of Gentiles (8:10; 15:28), a Roman army commander and a Canaanite woman. Jesus’ three parables told in the temple on the week of his death – the two sons, the vineyard and the wedding feast (21:28 – 22:14) – all make the point that Gentiles will be welcome in the kingdom of God. Throughout Matthew’s Jewish-flavored Gospel story, the Gentile “outsiders” are presented positively.

Jesus was in the process of forming his disciples for their Gentile mission, one in which they would need to reposition themselves in relation to “the outsider.” The “us versus them” mentality that dominated first century Judaism, and is indelibly stamped on humankind, would have no place in the kingdom that Christ was in the process of inaugurating. We see this way of thinking at work wherever migration takes place; indeed, at the time of writing, various nations are considering how to respond to Syrian (Muslim) refugees. Chinese villagers who have migrated into city are literally the “outsiders” (外地人), the very people to whom kingdom citizens must be sensitive. As followers of Christ and citizens of his kingdom, we are conscious of his desire to embrace the outsider.

As for the migrants themselves, apart from the lack of institutional resources like medical care and education, perhaps the greatest felt need is the intangible need for community and a sense of belonging. In typical Chinese village life, generations have grown up together in an extended network of family relationships. The movement of peoples over the past 35 years has torn to shreds this family fabric, leaving people to live isolated and solitary lives in the city while the elderly back in the village are stripped of the younger generation caring for them, like they cared for their parents.

Community centers are a means in which the church can offer the “relations of grace” and the “reality of community.” Joann was born in Beijing (and thus possesses a Beijing hukou) and, after completing her bachelor’s degree in China, went to the United States for graduate work. There she completed three Masters degrees and, more importantly, met Christ and received good discipleship training. When it came time for her to return to China, she believed that it was actually Christ sending her back to her homeland on a mission. Joann had become aware of the millions of migrants that had flooded her home city of Beijing, and wondered if this might be the people Christ was calling her to serve. As an accomplished woman with three Masters degrees, fluent in English and possessing a Beijing hukou, she could have easily landed a well-paying job. Instead she chose to find a poor migrant school and to teach English to the children there, working for a fraction of her true earning potential.

Along the way Joann married Joshua, himself a migrant from a poor village family, and in 2010 they opened the Agape Community Center on the outskirts of Beijing in the midst of a migrant cluster of about 70,000 people. The center has served families in a number of ways. First, for primary age children whose parents are both working, it offers them a safe place to go after school. Volunteers from nearby universities tutor the children every day after school, helping in a small way to make up for their substandard education. Second, it has functioned as something of a “family room” for the community. With ping-pong and pool tables, a reading room and a games corner, people of all ages have found a place of escape from their tight living conditions. Third, Agape has brought families together through video nights, regular outings and special celebrations. At Mid-Autumn festival and Christmas, the center will hold special events especially catered to families. Each year, teams of outside volunteers will hold a summer camp in the center. On the final day of the camp, parents and children will spend a rare day of play together somewhere, such as a water park.

Agape has been able to recruit a number of regular university volunteers, but to this point have been unsuccessful in recruiting city churches to become involved. Though several local pastors have indicated interest, but in nearly six years of operation no local churches have engaged in the ministry.

Apart from the community center approach, migrant churches can offer the relational connections so needed. Over these years, I have become close friends with many migrant church planters who, until the last two years, were able to plant many churches quickly. Recently central government policies have made it more difficult for migrants to reside in the city, and this has caused church growth to slow significantly. However, the hundreds of churches sprinkled throughout the city’s migrant areas, present the possibility of relationship to the sojourner.

V. METHODS OF SERVING CHINA’S INTERNAL DIASPORA: EMPOWERMENT, CHRISTIAN MULTIPLICATION AND THE FULL CIRCLE

The goal of Matthew’s Gospel is the final commission, where Christ’s authority and mandate become universal in scope. In that final commission the word “all” is used four times to express Christ’s position (“all authority”) and presence (“with you always”), as well as the extent of their ministry (“all nations” and “all I have commanded you”). The entire thrust of Matthew’s Gospel is missional, a story of Jesus preparing his disciples to carry the message and ways of his kingdom throughout the world, and they in turn preparing the world for final judgment (chapters 24-25). Jesus’ final eschatological parable, given just prior to his betrayal and death, reveals that his kingdom citizens are marked by a holistic care for “the least of these,” the hungry, thirsty, naked and imprisoned.

The ongoing movement of hundreds of millions of people throughout China – the “floating population” – is one of the best vehicles in the world today for fulfilling Christ’s global mandate. The father of republican China, Sun Yat-Sen, described the Chinese diaspora as like sand scattered throughout the world. Today’s internal diaspora is scattered like sand in every part of the nation. Christians who are part of this movement of people are more like seeds than sand, bringing the life and light of the kingdom to places in which they have been scattered.

Stephen is a 40-year-old church planter living, originally from Henan, now living in the southern part of Beijing. He came to the city eight years ago with his wife and two children, found a job to support his family and began sharing the gospel. Some years back Stephen had attended a Bible school in his hometown, and from that time realized that his mission in life was greater than just working to support his family. Within two years after moving to Beijing, as a result of the gospel witness from both him and his wife, Stephen had planted two churches. He quit his job to focus his attention on building the growing body, and to date has planted six churches. Over these years he has been steadily training co-workers to assist him in caring for the growing flock.

In the last two years, the Beijing government has enacted policies that are forcing many migrants away from city. Some are moving to other, more welcoming cities, and some are returning to their home provinces, choosing to settle down in smaller cities close to their hometowns. Stephen is finding this to be an opportunity to commission his flock. Having spent years equipping them, he is now sending them to plant churches in other places. This year, two of his closest co-workers have been commissioned by his church, and have already planted new churches close to their own hometowns, one in Henan and the other in Hunan. From empowerment to multiplication, the mission has come full circle.

Another example of the missionary potential for China’s internal diaspora may be drawn from two co-workers, Moses and Gregory. Now in their mid-30’s, both have been planting churches in Beijing for over ten years. They met as teenagers in a village Bible school near the border of Henan and Anhui, a school that has operated for some 15 years. Each year young people graduate from that school, some become full-time evangelists or church workers, but most migrate to cities for work. Hundreds have been scattered throughout China, from Xinjiang in the far northwest to Shenzhen in the southeast, and virtually every major city in-between. Some are living among minority peoples in Guizhou and others among Uyghur Muslims near Urumqi.

Over the past year, Moses and Gregory have traveled throughout China to visit this slice of diaspora from their hometown. They are currently in the process of forming a leadership team, and working out a plan for better equipping these people to make disciples and plant churches in the places Christ has sent them. As people from the same hometown, most of whom know one another, they already share a common identity and are very willing to be part of such a “missionary fellowship.”

VI. CONCLUSION

By using Enoch Wan’s CORRECT approach, we have attempted to describe both the challenge and potential for missions to and from China’s internal diaspora, connecting the motive, means and methods to the missionary thrust of Matthew’s Gospel. Already the massive movement of peoples has borne great fruit for the kingdom, and has become a significant vehicle for the spread of the gospel. There is potential for even more if urban churches will be nurtured by Christ’s compassion and become willing to embrace the outsider.

Bibliography

Akay, Alpaslan, Bargain, Olivier and Zimmerman, Klaus. “Relative Concerns of Urban-To-Rural Migrants in China.” Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn. Discussion Paper No.5480. February, 2011.

Chan, Kam Wing. “China’s Hukou System Stands in the Way of Its Dream of Prosperity.” South China Morning Post. January 19, 2013. <www.scmp.com> (Accessed October 27, 2013).

Chang, Leslie T. Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2008.

Gifford, Rob. China Road: A Journey into the Future of a Rising Power. New York: Random House, 2008.

Hornby, Lucy and Lee, Jane. “China’s Urbanization Drive Leaves Migrant Workers Out in the Cold.” Reuters. March 30, 2013. <http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/03/31/us-china-urbanisation-idUSBRE92U00520130331> (Accessed October 27, 2013).

Knight, J. and R. Gunatilaka (2011). “Does economic growth raise happiness in china?” Oxford Development Studies 39 (1), 1-24.

Lanman, Scott and Zhou, Xin. “China Urban Migrants’ Cost Seen At Least 6 Trillion: Economy.” Bloomberg News. August 28, 2013. Bloomberg.com, August 2013. <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-08-28/> (Accessed October 27, 2013).

Miller, Tom. China's Urban Billion: The Story Behind the Biggest Migration in Human History. London: Zed Books, 2012.

Pao, Hsiao-Hung. Scattered Sands: The Story of China’s Rural Migrants. New York: Verso, 2012.

Qi Dongying, “The Mark of New Generation Migrants: Most Are Unwilling to Return Home,” news.xinhuanet.com/edu/2011-09/21/c_122069435.htm.

Reid, Brenda and Youngman, Myron. “The Moving Population: An Introduction to the Urban Migrants of Modern China,” Kaifa Group, Commissioned by China Source. March 2009, 1-34.

Sun, Wanning. Subaltern China: Rural Migrants, Media and Cultural Practices. London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014.

Wan, Enoch. “Rethinking Missiological Research Methodology: Exploring a New Direction.” Global Missiology, Research Methodology. October 2003. www.globalmissiology.net.

__________. “Mission among the Chinese Diaspora - A case study of migration & mission” Missiology, Jan. 2003.

Wan, Enoch and Anthony Francis Casey, Church Planting Among Immigrants in US Urban Centers: The Where, Why, and How of Diaspora Missiology in Action. IDS-USA (Institute of Diaspora Studies), Portland, OR. 2014

Wu, Fulong and Zhang, Fangzhu and Webster Chris, editors. Rural Migrants in Urban China: Enclaves and Transient Urbanism. Routledge Contemporary China Series. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Robert K. Yin, Case Study Research: Design and Methods: Design and Methods. Sage, 2014.