Building Castles in the Sky: A Case for the Use of Indigenous Languages (and Resources) in Western Mission-partnerships to Africa

Jim Harries

Published in www.GlobalMissiology.org April 2016

Note: paper originally presented at the Vulnerable Mission Workshop held at the Ralph D. Winter

Research Center, Pasadena California, 24th Sep. 2013.

|

Abstract

A

case study illustrates the importance of issues addressed in this article that

are all too often occluded in missionary reporting. The use of one language in

cross-cultural discourse conceals important difference from view. This means

that ‘asking questions’ of the cultural other is a fraught exercise full of

traps and blind spots. Different means of overcoming this difficulty are

proposed. Much inter-cultural discourse results in building castles in the sky.

The use of local languages and resources is found to be critical to the success

of inter-cultural partnerships with believers and churches in the majority

world.

A

case study illustrates the importance of issues addressed in this article that

are all too often occluded in missionary reporting. The use of one language in

cross-cultural discourse conceals important difference from view. This means

that ‘asking questions’ of the cultural other is a fraught exercise full of

traps and blind spots. Different means of overcoming this difficulty are

proposed. Much inter-cultural discourse results in building castles in the sky.

The use of local languages and resources is found to be critical to the success

of inter-cultural partnerships with believers and churches in the majority

world.

Introduction

Enormous fanfare accompanies the sending of Western missionary personnel and the launching of new projects. Sending home of missionaries and closing down or failure of projects happens quietly. Few know the details. The masses of people who end up deeply hurt in the process have little voice. Why should they have, they failed, and who wants to listen to failures?

Frequent ‘failures’ in mission projects arise, in part at least, because of ignoring cultural gaps. They are not ignored in theory; people know they are there. Yet they are ignored in practice when both sides use one language and assume that they comprehend one another. Such practical ignoring of cultural differences results in castles being built in the sky. Cultural contexts affect language impacts more deeply, broadly and profoundly than is often realised.

No formula can make cultural gaps disappear. There is no alternative to hard graft, this article suggests. This article looks at ways in which this hard graft can be engaged. It explores how a missionary can best go about learning the ‘culture’ of another and engaging with those who are different. Practical field-tested recommendations are given on how to relate in inter-cultural partnerships.

Case Study

A case study about certain missionaries’ experience on the field that was presented orally at the conference on vulnerable mission held in Pasadena on 24th September 2013 has been omitted here because of its sensitive nature.

… If the above sounds melodramatic, I apologise. It happened. Similar things keep happening all over Africa, and probably all over the majority world. I hope my readers aren't thinking that they could easily have avoided the embitterment and tensions that resulted in the termination of the above missionaries’ assignments. The couples I refer to above were and are intelligent mature people.

A

dilemma faced by new missionaries or development workers when they reach the

field is: who to listen to. Local people understand the context very well, but

may be less well informed regarding the objectives of the missionaries

concerned. Fellow missionaries who have been around for longer probably

understand more about what their new colleagues are trying to achieve, but may

not agree with the way that local people want to help them to implement their

goals. Would the above missionaries have avoided the pitfalls they fell into

had they chosen to listen to me as well as to the African people? Possibly. The

stakes however were high. They represented a lot of money. Had they listened to

me, and told local people ‘we want to do it this way because Jim told us’, I

might have got dragged with them further into the downward spiral. There was

too much money involved. The money they carried, or potentially carried, gave

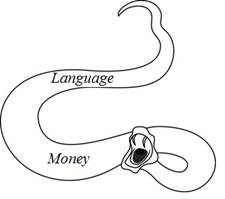

my colleagues power in a system that they, at the time, did not understand.

Words shared with them using a common Western language (English) deceived them

into thinking that they ought to be able to function effectively in that

context. The use of Western languages in Africa can be likened to a curse. The

willingness of Westerners to invest a lot of money while communicating through

those languages, can give the curse a terrible bite. A prerequisite to being

able to comprehend contextual advice is really, I am here suggesting, the

willingness to build on other than foreign money, and a readiness to engage

ministry using local languages.

A

dilemma faced by new missionaries or development workers when they reach the

field is: who to listen to. Local people understand the context very well, but

may be less well informed regarding the objectives of the missionaries

concerned. Fellow missionaries who have been around for longer probably

understand more about what their new colleagues are trying to achieve, but may

not agree with the way that local people want to help them to implement their

goals. Would the above missionaries have avoided the pitfalls they fell into

had they chosen to listen to me as well as to the African people? Possibly. The

stakes however were high. They represented a lot of money. Had they listened to

me, and told local people ‘we want to do it this way because Jim told us’, I

might have got dragged with them further into the downward spiral. There was

too much money involved. The money they carried, or potentially carried, gave

my colleagues power in a system that they, at the time, did not understand.

Words shared with them using a common Western language (English) deceived them

into thinking that they ought to be able to function effectively in that

context. The use of Western languages in Africa can be likened to a curse. The

willingness of Westerners to invest a lot of money while communicating through

those languages, can give the curse a terrible bite. A prerequisite to being

able to comprehend contextual advice is really, I am here suggesting, the

willingness to build on other than foreign money, and a readiness to engage

ministry using local languages.

Two Contexts

Western people who engage with their African partners using English are forgetting something very important. They are forgetting the cultural gap between them and the Africans who they are endeavouring to reach. Often they seem to assume that cultural differences disappear when one uses one language. I think this is illogical: how can cultural differences disappear as a result of someone’s having learned a language? They cannot. At best they go into temporary hiding.

Let me look at some examples. I want to begin with the more involved one. It is widely acknowledged that African people have a monistic worldview. That is – for them the spiritual and material are intertwined into one. This has many ramifications that I have explored in more detail elsewhere (for example, see Harries 2013a). It means that in Africa a search for the truth about God always happens in hand with a search for prosperity, including material prosperity. This is very different from the widespread Western view in which spiritual and material are relatively distinct categories. To accuse a Westerner of engaging spiritually in pursuit of material gain is to charge them with some kind of immorality. For an African, this is normal. To be overheard by Westerners so ‘accusing’ African Christians is to be considered offensive for having stated what in Africa is merely the order of the day.

Now let me give a simple example. If I say "I want two" while pointing to some loaves of bread in a shop, then it is clear that I want to purchase two loaves of bread. If I say "I want two" after being asked for how many months I want to insure my car, then it is clear that I want two months of insurance cover. The impact (meaning) of "I want two" is not determined by the words that I use, but by the context in which they are said (pointing to bread or searching for insurance). When it comes to mission engagement, there are two important contexts – the Western one and the African one. These contexts determine the impact (i.e. meaning) of anything said or written. A Westerner, although they might make a few adjustments to the context of engagement, will typically understand what is said in relation primarily to their Western context. The African person will understand the same in relation primarily to their own African context. The interpretations that arise can as a result be vastly different.

The depth and breadth of the above alluded to differences are worth emphasising a little. Simple examples can be given. For example, a meeting advertised as starting at 2.00 p.m. may begin at 2.05 pm. in one context, and at 4.30 p.m. in another. "He is wealthy" may mean that he earns $1000 per month in one context, but $20,000 per month in another. These kinds of difference are the tip of the proverbial iceberg. I do not have time in this article to go into them in more detail here. For a small glimpse of what an African context might look like I refer my reader to a small storybook I had published a few years ago (Harries 2011a).[1]

Resolving the Confusion

Because the issues are deep and wide, solutions must be deep and wide. That is to say: there is no formula to crossing cultural gaps. There is only hard graft. No end of prior training or pre-field orientation can resolve all the issues that a new missionary will face. I hope it is clear that doing your communication with Africa from your computer at home does not resolve the above difficulties. If anything it accentuates them – as the person sat at their computer in the West is missing many of the contextual signals that a missionary on the ground is able to see, and that might contribute to becoming culturally enlightened. I propose that there are three alternative ways of trying to deal with this confusion:

One way in which people are these days attempting to get around the above issue, is by implicitly agreeing the context in relation to which one will be communicating. The implicit agreement in the globalised world today is that we should speak in relation to the American context.[2] Hence the global education system is America (UK) centred. The less America-focused education becomes, the less useful it will be on this reasoning, because the less effective it will be at enabling clear communication. Enormous efforts are being engaged at spreading American culture globally. Yet we still have to ask ourselves whether they are enormous enough. Is what is being endeavoured, to give the whole global community a sufficient contextual background so as to be able to correctly understand Western English, even possible? Unfortunately, I suggest, it is not. (For more on this question, see Harries 2013a.) The same, of course, applies should a particular African cultural context be taken as global ‘base’. Imagine converting the whole of the American educational system into one that functions in an African language and according to certain African cultural presuppositions. Such a project would seem ridiculously impossible and unacceptable. It would take years of intensive teaching before many Americans really even began to ‘get it’. Can Americans begin to imagine making conscious efforts at using language in business when in America, as if they are in an African context?

A second way to try to resolve the above confusion is to use a cultural broker or interpreter. Cultural brokers or interpreters should be bi-cultural. Their role would be to hear one person (e.g. the African) speak, and then to interpret what they are saying in such a way as to give an American an appropriate understanding. (I intentionally say ‘an understanding’ as translation is rarely precise.) This person is always in the middle between the American and the African. Their role is no less important, but perhaps more difficult, if both the American and the African are using the same language, e.g. English. Unfortunately the role of this cultural interpreter is extremely fraught, especially if both parties know the same language, such as English. Can they really interpret all conversations? Will they be there for every informal exchange? In practice, such a cultural interpreter gets hit from both ends, then ignored, then pushed out of the way.

The third way is to use two languages. That is – for a Western language to be used with respect to Western cultural presuppositions, and an African language to be used with respect to African cultural presuppositions. The resultant need for translation leaves a gap. This gap must be filled by someone familiar with both languages (and also familiar with both contexts). The presence of this gap, closed only by a process of translation, will make the inter-cultural nature of what is going on visible. For example, if a Westerner is told that an African called David said that “the Gospel is strong” then he should realise that he actually said something else. For example, he might have said “injil nigi teko”, that happened to be translated into English as “the Gospel is strong”. It could instead have been translated as “the Gospel has strength” or “the name of Jesus is effective in driving out ghosts” or “the Word is powerful” or … ad infinitum. David never said that “the Gospel is strong”. He said “injil nigi teko”; which could be quite different. (It should be noted, of course, that even if an African called David says in English that “the Gospel is strong” this will quite likely be a translation in his own mind from injil nigi teko. In this case also, the implications of use of the latter African language and not English must be considered if David is to be correctly understood.)

There are numerous, if not endless reasons why it is good for a people to use their own language(s) for their own discourses. I am here merely touching on a few of those reasons. I have made more reference to them in other places, such as Harries (2013b). Here I am pointing to the advantages of making a link between a language and its underlying presuppositions explicit. I am suggesting that English be used with respect to Western contexts/presuppositions. Then when an African language be used, it be in relation to African contexts/presuppositions. A simple example of this kind of ‘switch’ occurs all the time in East Africa: Time is in East Africa told as starting at zero at 6.00 a.m. and 6.00 p.m. People translate instantaneously. For example 9.00 a.m (English) becomes saa tatu (i.e. 3 a.m.) in African languages or 10 o’clock in African languages becomes 4 p.m. in English. People regularly do such translation almost without thinking. Could they do the same for other cultural peculiarities apart from time?

Asking Questions

I want to draw on the discussion above to more thoroughly address the question of learning culture. I often hear it said that when in a foreign culture one should ask a lot of questions. I would like to query this advice. Not that asking questions is wrong as such, but it has severe limitations To begin with, expecting answers to questions one asks presupposes having a position of power. Why otherwise should local people use up their time answering you? Putting aside colonial attitudes can be to not ask questions. I often find that questions visitors ask of the context I live in in Africa do not make sense. The actual complexity of the situation that a question assumes to be simple[3] can make it difficult or even impossible for someone to give a reasonable answer. The same applies to questions asking things that are confidential, embarrassing, ambiguous, points of contention, over-revealing, compromising, politically loaded, and so on.

Myself having been brought up in the West, helps me to perceive where a Western questioner is coming from. My African colleague may have little clue on this. Questions can come at right angles to ways in which life is understood. They may make no sense at all, but they are demanding answers. Yes is usually preferred as an answer to no. This applies whether or not a question is understood. Better an answer than no answer. Not to have an answer can be embarrassing, and make the African (who has spent decades in school learning English) look stupid. All of the above put together easily results in the visiting Westerner building intricate castles in the sky. The probing Westerner works forward deductively building their knowledge base one-step at a time. Usually too late (after the project has been started, once the money is invested, after the article or book has been written …) they realise that what they are building on has no foundation! Imagined vacuous commonalities in understanding end up underlying foundations for communication over wide varieties of relationship for many years to come. Is it any wonder that projects fail? It is time to stop blaming the ‘ignorant national’ when it is (our) Western communication strategies that are creating imaginary castles.

Listening to fresh (i.e. newly arrived in Africa) Westerners talking to Africans can be like a comedy show. It can be absolutely laughable. I imagine at this point my reader or listener might be saying: give us an example! The difficulty here is exactly that examples that Western people understand are difficult to find. They are difficult by definition. They are difficult to illustrate exactly because the cross-cultural situations we are referring to are not familiar! If they were familiar, then I would not be needing to write this, as we would all be in agreement already.

What can help us to see our way through the above puzzle is an analogy. The analogy that seems to illustrate the contorted dynamic of communication between cultures is a comparison between sports. Sports, like cultures, are living and are active. Then I still hit a problem: my limited knowledge of sports, especially sports that are popular in the USA as against in the UK. Let us compare soccer with basketball. Try commentating on a game of basketball using the language of soccer. Trying to do this brings up endless problems and questions! Such as – is the basket the goal? How many players are there? How does one describe one person passing the ball to another without it appearing to be a foul (touching the ball with one’s hands)? Is one or is one not allowed to be off-side? Try this as an exercise. If you begin to laugh incredulously at yourself, then you are beginning to see how laughable can be conversations between Africans and Brits. (For more on this see Harries 2011b.)

Although Western missionaries finding themselves having a language in common with the African people they are reaching can be advantageous, it can also be a drawback. The drawback is that one can assume levels of understanding that are actually not there. It is healthy in such a situation to assume one knows very little until one has a thorough grasp of an African language. Instead of asking a lot of questions, a better learning approach may be to put oneself into a position in which one can observe ways in which local language uses correspond to actions by the actors concerned.

The Pincer Trap of Mission Partnerships

I

want to illustrate the kind of thing that can happen today, and the seriousness

of the predicament we are in, by another illustration. Just occasionally a

young person, or even an older person, takes the kinds of advice given by the

AVM (Alliance for Vulnerable Mission) seriously, and sets out onto the mission

field with a great urge to truly engage the Gospel of Christ with the culture

they are meeting. Let us imagine that this person, who we’ll call Bill, manages

to learn the language of the people they are reaching. Bill learns the language

‘properly’; in hand with and not separately from its culture. He finds that by

avoiding being a source of Western money, he is able to identify closely with

the local community. He begins to acquire a deep and profound understanding of

what is happening and what the Western missionary force perhaps ‘ought to do’.

I

want to illustrate the kind of thing that can happen today, and the seriousness

of the predicament we are in, by another illustration. Just occasionally a

young person, or even an older person, takes the kinds of advice given by the

AVM (Alliance for Vulnerable Mission) seriously, and sets out onto the mission

field with a great urge to truly engage the Gospel of Christ with the culture

they are meeting. Let us imagine that this person, who we’ll call Bill, manages

to learn the language of the people they are reaching. Bill learns the language

‘properly’; in hand with and not separately from its culture. He finds that by

avoiding being a source of Western money, he is able to identify closely with

the local community. He begins to acquire a deep and profound understanding of

what is happening and what the Western missionary force perhaps ‘ought to do’.

Missionary Bill works within a larger organisation. There is already an established church amongst the community to whom he is ministering. As a result, people from the sending mission back at home are in communication with the national church leaders. Bill’s boss, who does not have a profound cultural understanding of the African culture at all, speaks to the African church leader in English. When important decisions need to be made, Bill may or may not be consulted. Even if he is consulted, because the African church hierarchies’ own leaders are in direct discussion with the mission leaders in the West, Bill’s voice carries relatively little weight. The sending office is reasoning that if there is an established African church with leaders who are familiar with Western languages, then why should they go through a missionary?

Usually

the ‘important decisions’ that I mention above regard money. The Western people

who make these decisions are not those with African linguistic or cultural

knowledge. Bill, who has devoted himself to informed missionary service, has

been turned into a sideshow. Not much later, after being turned into a

sideshow, Westerners begin to compare Bill’s words with those of African

leaders. Bill (when he communicates back ‘home’ using English) wants to help

his supporters to understand by interpreting African words to them in a way

that he considers will be helpful. The interpretations given by Bill are

different from those of the Africans. When the African church leader is the

recognised authority, then Bill is easily condemned. Quite often Bill is forced

to go home. On other occasions, because of his cultural and linguistic

knowledge, he is forced to resign his position in the larger sending mission

and to become independent. Here’s a giant little-seen elephant in the room.

Usually

the ‘important decisions’ that I mention above regard money. The Western people

who make these decisions are not those with African linguistic or cultural

knowledge. Bill, who has devoted himself to informed missionary service, has

been turned into a sideshow. Not much later, after being turned into a

sideshow, Westerners begin to compare Bill’s words with those of African

leaders. Bill (when he communicates back ‘home’ using English) wants to help

his supporters to understand by interpreting African words to them in a way

that he considers will be helpful. The interpretations given by Bill are

different from those of the Africans. When the African church leader is the

recognised authority, then Bill is easily condemned. Quite often Bill is forced

to go home. On other occasions, because of his cultural and linguistic

knowledge, he is forced to resign his position in the larger sending mission

and to become independent. Here’s a giant little-seen elephant in the room.

The question of the language of ministry is inextricably linked to the question of resources. The way for the above mission to prevent the otherwise inevitable pincer movement from discrediting their missionary is through ceasing to be a source or channel of resource provision to the African church. To load Bill, the missionary on the ground, with the responsibility of making key decisions on large amounts of resources, may well force him to remain isolated from his local community. Unless he says what the local African people would have said, his position can quickly be untenable. To bypass him will sideline his key ministry, and can easily in due course result in his being condemned. In the AVM[4] we say that it is important for some Western missionaries to carry out their ministries, or at least certain key ministries, using local languages and resources. Those missionaries need a backing. The above tell us that if the people who support their incarnational ministry are also heavily involved in providing funding to nationals while communicating in Western languages, they will easily find themselves working against the incarnated missionary. Those who decide to work in Africa using Western languages and resources in their ministries ought to realise some of the above implications of what they are doing.

Conclusion

Inter-cultural partnerships that ignore real cultural differences easily end up troubled. Different strategies for taking account of cultural differences are here discussed. One of these is the use of two languages to represent two cultures. Differences between cultures are more fundamental than one language can ever articulate about life in the realm of the other. A clear identification of cultural differences is enabled by Western missionary initiatives that avoid seeking to build ‘castles in the sky’ outside of the West using Western money.

The article concludes by looking at a practical case in which a missionary from the West sets out to engage in ministry in the majority world using indigenous languages and resources. It shows how easily contemporary orientations to mission partnerships result in such a missionary’s efforts being sidelined and then condemned. This article suggests that not only do we need missionaries who are ready to partner in a vulnerable way, i.e. with local languages and resources. Those missionaries also need support structures that can avoid the pincer-crunch that easily arises from naive efforts at inter-cultural relationship based on Western languages and resources.

Bibliography

Harries, Jim (2013a). Communication in Mission and Development; relating to the church in Africa. Oregon: Wipf and Stock.

Harries, Jim (2011a). Three Days in the Life of an African Christian Villager. Sandy, Bedfordshire; Authors on line.

Harries, Jim (2011b). ‘Is it Post Modern, or is it just the Real Thing? Challenging Inter-cultural Mission – a Parable’ Global Missiology Vol 3, No 8, (April 2011). (http://ojs.globalmissiology.org/index.php/english/article/view/585).

Harries, Jim (2013b). ‘The Immorality of the Promotion of Non-Indigenous Languages in Africa.’ Global Missiology Vol 2, No 10 (2013): Language, Culture and Mission. http://ojs.globalmissiology.org/index.php/english/article/viewFile/1137/2635 (accessed January 7, 2013)

Prince, Ruth, 2007. Salvation and Tradition: configuration of faith in a time of death. 84-115 In: Journal of Religion in Africa, 37.