No Place Left: Strategic Priorities for Mission

Nathan Shank – August, 2016

A generation is coming, and may now be among us, who will usher the Great Commission to its finish line. The “modern mission movement,” now in its third century, is heir to unprecedented global research and resources unavailable to any previous generation.[1] The 20th century surge in missiology has resulted in a renewed focus on apostolic function and zeal among traditional bases of missionary sending[2] and unprecedented mobilization in the majority world.[3] Into this context, the Spirit’s “work” in and through the apostle Paul and his co-workers speaks to a generation longing for the second coming. “No Place Left” is, most simply, a call to look at the New Testament with the question, “what is possible?” It is a call based upon Scripture to re-focus on strategic priorities for mission.

The Need for Clarity amidst Unprecedented Mobilization

Following the “Great Century” of missions, the 20th century has been called the “Global Century.”[4] As the history of the 20th century is written it will be known for unprecedented efforts in missionary mobilization. Efforts like Urbana, The Lausanne Movement, AD 2000, and others have resulted in practical tools for research, an explosion of networks for sending,[5] and the development of hundreds of world evangelization strategies.”[6] Today, previous mission targets are becoming 21st century sending bases.[7] The 21st century carries compounded potential as the “majority world” takes up mission among Unreached People Groups. As ranks of the global mission force swell, biblical priorities and finish line metrics of pioneering mission must be constantly clarified. At the same time, there has been increasing ambiguity among traditional sending bases as to what truly constitutes “mission.”

The Need for Clarity amidst Sending Base Confusion

For historic sending bases in the West, elements of mission—people group engagement, cross-cultural proclamation, and pioneer church planting—have sometimes conflicted with the inherited ministry patterns of a majority-Christian context. In traditional Christian contexts misunderstandings abound regarding the unique function of the pioneering missionary within the broader mission of the church.

Patrick Johnstone lamented, “To many today, mission means little more than the general work of the Church in the world to alleviate social ills but with the evangelistic or missionary sending component ignored or despised.”[8] Issues like social justice and cultural transformation carry potential for confusing the foundation-laying role of missions with the ongoing role of the local church as a change agent within its society. The distinct nature of pioneer missions is in danger of being swallowed up in the broader missio dei of the Church.[9]

Amidst unprecedented mobilization, and sending base confusion, where does the 21st century missionary find direction for his or her role? How do we define strategic priority in pioneer contexts? Finally, does the scripture provide finish line metrics for mission work? We must return to the first century to ask these questions of the Scriptures. [10]

“No Place Left” for Paul to Work

Imagine a great artist, even as the paint dries, reflecting on his masterpiece. Imagine the artist, knowing it would be preserved for posterity, detailing the process and priorities that led him to the finished work. Surely, artists of later centuries would treasure the summary as a foundation for their craft. In Romans, the Holy Spirit ensured such a record exists for mission.

I have written to you quite boldly on some points, as if to remind you of them again, because of the grace God gave me (16) to be a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles with the priestly duty of proclaiming the gospel of God, so that the Gentiles might become an offering acceptable to God, sanctified by the Holy Spirit. (17) Therefore I glory in Christ Jesus in my service to God. (18) I will not venture to speak of anything except what Christ has accomplished through me in leading the Gentiles to obey God by what I have said and done—(19) by the power of signs and miracles, through the power of the Spirit. So from Jerusalem all the way around to Illyricum, I have fully proclaimed the gospel of Christ. (20) It has always been my ambition to preach the gospel where Christ was not known, so that I would not be building on someone else’s foundation. (21) Rather, as it is written: Those who were not told about him will see, and those who have not heard will understand.” (22) This is why I have often been hindered in coming to you. (23) But now that there is no more place for me to work in these regions, and since I have been longing for many years to see you , (24) I plan to do so when I go to Spain. Romans 15:15 – 23.

Romans 15:15-23 is a 1st person account of the Holy Spirit’s leadership in the work fulfilled through Paul’s missionary journeys (Acts 13-20).[11] Based on Holy Spirit initiative (v. 15-16), authority (v. 16), direction (v. 19-20) and power (v. 19), Paul not only claims to have fulfilled (pleroo) the gospel[12] he further states, “there is now no place left for me to work” (v.23).[13]

Writing on Romans 15 P.T. O’Brien stated, “Paul provides significant insights into what he had been doing and what were his hopes for the future. He thus throws light on essential features of his ministry, including goals and motivating power, it’s content and extraordinary results, as well as his all-consuming ambition to proclaim Christ where he had never been heard.”[14] By the power of the Spirit, Paul was not only a great artist, his work was chosen as the example in the inspired Word of God. Within the inspired account, Paul’s summary offers a glimpse at the finish line he crossed. To the degree his Roman readers determined the process and priorities by which he was led to fulfill the work, the strategic priorities and key results of mission were revealed.

Before proceeding to the strategic priorities of mission revealed in Romans 15 the question must be asked, “Was Paul simply the beneficiary of circumstances unique to the first century, or can his example and the success of his mission be expected today?”

“No Place Left” in Paul’s 1st century context

Paul’s summary statement leads us to ask, “Was Paul simply the beneficiary of circumstances unique to the first century?[15] How might his 1st century context compare with 21st century mission fields?” Answering these questions demands a broader perspective on the place of Romans in the Acts timeline and a description of the mission field Paul engaged.

Romans in the Acts Timeline

Romans 15 and 16 offer evidence for the timing of Paul’s writing. Commentators have associated Erastus, “the director of public works,” with archeological finds in the city of Corinth (Rom. 16:23).[16] Phoebe’s presence in Romans 16:1 suggests an origin of the letter in close proximity to Cenchreae. Most helpful is Paul’s mention of the Macedonian and Achaean church’s faithfulness in the offering collection for the saints in Jerusalem (Rom.15:25-26). Based on these markers Paul’s Romans 15 summary fits into the timeline of Acts (Acts 20:3).[17] As Paul paused in Corinth, he came to the conclusion his work in those regions had been fulfilled. Placing Romans in the Acts timeline offers a secondary context for understanding Paul’s summary in Romans 15.

The Acts 13-20 Timeline

One surprising aspect of Paul’s missionary career was its relatively short tenure. Based on Luke’s description of Paul’s “unhindered” house arrest in Rome (Acts 28:30-31) it is generally accepted Nero’s persecution had not yet begun. This places Acts 28 before the year 64 AD.[18] Luke’s mention of two years for both the Roman (Acts 28:30) and Cesarean (Acts 24:27) imprisonments place Paul’s Jerusalem arrest no later than mid AD 59. Similarly, Luke’s various accountings for time throughout the narrative devoted to Paul provide cross references for Paul’s epistles (Acts 9:19, 23; 11:26; 14:28; 15:36; 18:11, 18, 23; 19:8, 10; 20:31; 21:4, 8, 10; 21:26; 23:12, 31-32; 24:1, 24; 25:23; 27:27; 28:11).

The timeline of most value in the Pauline epistles is recorded in Galatians 1:15-2:10. Dependent upon the date of Paul’s conversion (Acts 9:3, ca 33-35 AD) and the start date for Paul’s “14 years later visit” to Jerusalem (Gal. 2:1)[19] scholars offer 12-15 years for Paul’s journeys, (Acts 13-20, ca. AD 46-59).[20] This means, Paul’s “no place left” summary was the work of little more than a decade.[21]

The Challenges of Population and Geography

Rodney Stark, in his book, The Triumph of Christianity, has gone to great lengths to estimate Christian population percentages in the first century. Stark bases his estimates on a “stable imperial population of 60 million” in the Roman Empire throughout the first century.[22] Where archeology has suggested population densities, the Mediterranean coast between Jerusalem and Rome could have conservatively held up to half the 1st century Roman population.[23] If Stark is correct, Paul’s Romans 15 summary describes his work among 20 to 30 million in population.

Amidst this population, Paul was on the move. The area Paul describes in Romans 15, between Jerusalem and Illyricum was 300,000 square miles.[24] Paul’s travels within his three missionary journeys (Acts 13-20) covered a distance of more than 13,000 kilometers.[25] These travels were not without their challenges. In 2 Cor. 11:26-27 Paul states, “I have been constantly on the move. I have been in danger from rivers, in danger from bandits, in danger from my fellow Jews, in danger from Gentiles; in danger in the city, in danger in the country, in danger at sea; in danger from false believers. I have labored and toiled and have often gone without sleep; I have known hunger and thirst and have often gone without food; I have been cold and naked.”

The Challenges of Hellenistic Culture

Paul’s targets were the epicenter of Hellenistic culture. The provinces between Jerusalem and Rome were saturated by pluralistic faith, immorality and philosophical barriers to the tenets of the Christian gospel.

Paul’s work consistently brought him into conflict with ancient, well funded pagan worship (Acts 14:11-20; 16:16-24; 19:23-34). Adolf Harnack wrote, “Christianity and paganism were absolutely opposed. The former burned what the latter adored, and the latter burned Christians as guilty of high treason.”[26] Beyond zeal for pagan deities, 1st century philosophy also carried significant influence over Paul’s targets. Speaking of the various philosophies in the Grecko Roman world Latourette believed, “it (Christianity) faced the competition of many systems which appeared to have a much better prospect of survival and growth.”[27]

Along with these challenges, 1st century illiteracy,[28] various challenges with immorality,[29] and significant opposition from both Jews and Greeks frame Paul’s 1st century context.[30] In his reflection on these challenges Harnack reminds his readers of the danger of syncretism in the 1st century. According to Harnack, Hellenism presented a tide of religious, philosophical and ethical syncretism for the first century evangelists.[31] Grasping the contextual challenges; dangerous travel, staggering population and the entrenched religious and philosophical barriers Paul faced supercharges his summary in Rom. 15:23. Considering the relentless persecution Paul faced in the relatively short tenure of his mission his conclusion is remarkable. “There is now no place left for me to work” (v. 23).

By comparison we may conclude it is the 21st century missionary who is the beneficiary of unique circumstances. The rise of global literacy, a system of global transport and commerce, have brought the peoples of the world into reach. Access to global research, media for mass seed sowing and the resources of a global, mobilized work force would certainly have been advantages the apostle Paul would have leveraged. Certainly some combination of the challenges Paul faced await the 21st century missionary. When such barriers are encountered missions can find fellowship and direction in the example of Paul.[32]

Imagine the 21st century missionary facing such challenges. Targeting the centers of organized paganism, in the midst of severe persecution and philosophical opposition, with a target population of 20 million living across 300,000 square miles, what would be the expectations for 12-15 years of mission work? Why not, “no place left?”

“No Place Left”: Strategic Priorities for Mission in Romans 15 and Acts 20

Based on Paul’s statement, “I have fully proclaimed the Gospel” (v. 19) and “there is no place left to work” (v. 23), the question must be asked, “What was the “work” that had been accomplished?”[33] Snodgrass argues, “The work in question here cannot be simply a general term for ministry. It must refer to a specific set of activities and not those that are enjoined upon the church at large. The reason is that ministry in its broad sense could not possibly have been ‘fulfilled’ in that region.”[34]

What then was the “work” Paul had accomplished? The answer is Paul’s apostolic mission. Paul’s summary of his “work” is not the normative strategy often argued. It is more a description of Holy Spirit inspired “strategic priority” in the work he had fulfilled.[35] Romans 15 describes Paul’s fulfillment of strategic priorities for mission. Each of these priorities was initiated, authorized, directed and empowered by the Spirit of God.

Paul’s Priorities were set by the Spirit[36]

“Yet I have written to you quite boldly on some points to remind you of them again, because of the grace God gave me to be a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles. He gave me the priestly duty of proclaiming the gospel of God, so that the Gentiles might become an offering acceptable to God, sanctified by the Holy Spirit.” Romans 15:15-16.

“I will not venture to speak of anything except what Christ has accomplished through me in leading the Gentiles to obey God by what I have said and done—by the power of signs and wonders, through the power of the Spirit of God.” Rom. 15:18-19a.

Paul wanted to be sure the Roman audience understood. It was not a strategy, a tool or a work ethic that “fulfilled” the “work”. God used Paul. God set the agenda. The demonstration of the Holy Spirit’s power confirmed the strategic priorities of mission in Paul’s life. Paul’s summary in Romans 15 was the culmination of a career led by the Spirit.

Paul’s mission “work” was initiated by the Holy Spirit. Acts 13:2 says, “Set apart for me Paul and Barnabus for the work to which I have called them.” According to Luke (likely based on Paul’s 1st person testimony) it was the Holy Spirit’s prerogative to set apart Paul and Barnabus for the “work”(Acts 13:2-4). While this was not the beginning of Paul’s ministry,[37] it did mark a significant transition in the book of Acts by which Luke initiates his focus on the ministry of the apostles, Paul and Barnabus.[38]

Secondly, Paul’s “work” was authorized by the Holy Spirit. In Galatians Paul defends the authenticity of his apostleship. We see the source of Paul’s calling and authority in Galatians 1:15-17, “But when God, who set me apart from my mother’s womb and called me by his grace, was pleased to reveal his son to me so that I might preach him among the Gentiles, my immediate response was not to consult any human being. I did not go up to Jerusalem to see those who were apostles before I was, but I went into Arabia.” Paul’s authority as a “sent one” was a matter of God’s choice and timing. Galatians 2:8 says, “For God, who was at work in Peter as an apostle to the circumcised, was also at work in me as an apostle to the Gentiles.” The work to which Peter was commissioned was the same as “the work” to which Paul had been called.

Third, Paul’s work was directed by the Holy Spirit. Throughout Acts the Holy Spirit is seen opening and closing doors for mission. The most recognizable example is the “Macedonian call” (Acts 16:9-10). Additional examples include, Acts 18:9-11; Acts 20:22-24; 1 Cor. 16:8-10. In 1 Corinthians 16, Paul informs the church his travel plans are uncertain because, “A great door for effective work (implied) has opened to me, and there are many who oppose me” (v.8). Paul then commends Timothy to the Corinthians stating, “When Timothy comes, see to it he has nothing to fear while he is with you, for he is carrying on the work (ergon) of the Lord, just as I am” (v.10).

Finally, Paul’s work was empowered by the power of the Holy Spirit. Where Paul proclaimed the Gospel, the Spirit confirmed the message with power (1 Cor. 2:1-5). Miracles of healing, (Acts 14:8-10; 19:11-12) exorcism, (Acts 13:9-11; 16:18; ), and endurance (Acts 14:19-20; 19:10,20) are often repeated in the description of Paul’s “work”.

Where the Spirit led, Paul prioritized the tenets of his mission. Paul’s Romans 15 summary, together with the context of the Acts 20 timeline reveals five such priorities for mission.

Priority #1 – Paul’s Mission was Pioneer in its Ambition

Romans 15:19-20, “So from Jerusalem all the way around to Illyricum I have fully proclaimed the Gospel of Christ. It has always been my ambition to preach the Gospel where Christ was not known, so that I would not be building on someone else’s foundation.”

Paul conceived his missionary “work” to be pioneering. The pioneer ambition proceeds directly from the Spirit’s calling of Paul to the Gentiles (“ethne,” Rom. 15:16, 16b, 18). W.P. Bowers called Romans 15:20 “Paul’s all-consuming ambition: to preach Christ where he had not been named.” The “where” mattered to Paul and was distinctly pioneer in nature. Bowers points out, Paul perception of “his role as initiatory in nature is apparent in the specific metaphors he applies to his vocation”. Examples include, “planting” (1 Cor. 3:6-9, 9:7, 10, 11), “laying foundations” (Rom. 15:20, 1 Cor. 3:10), “giving birth” (1 Cor. 4:15, Phlm. 10), and “betrothing” (2 Cor. 11:2).[39]

The calling of Paul as an apostle dictated the inevitability of movement (Gal. 1:1; Rom. 1:5; Acts 9:15; 26:16-18). The book of Acts records the Spirit’s leadership of Paul in the pioneer engagement of at least 4 Roman provinces.[40] By Acts 20, Paul had planted churches in no less than 10 significant Romans cities with evidence of evangelistic “ringing” into the surrounding country side in each province (Acts 13:49; 1 Thess. 1:8; 2 Cor. 1:1; Acts 19:10).[41]

To be “sent” on mission necessarily required pioneer advance.[42] Eckhard Schnabel believes Paul’s inclusion of Jerusalem and Illyricum suggests both movement and intentionality in his efforts.[43] P.T. O’Brian agrees, “What does emerge from this geographical reference is that Paul’s journeys were not ‘sporadic’, random skirmishes into gentile lands”.[44] As suggested, Paul’s movements were directed by the Holy Spirit. To obey his calling, Paul had to pioneer where Christ had not been named.

Priority #2 – Paul’s Mission required Gospel Proclamation.

“Because of the grace God gave me to be a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles. He gave me the priestly duty of proclaiming the Gospel of God, so that the Gentiles might become an offering acceptable to God, sanctified by the Holy Spirit.” Romans 15:15-16.

“By the power of signs and wonders, through the power of the Spirit, So, from Jerusalem all the way around to Illyricum, I have fully proclaimed the gospel of Christ.” Romans 15:19.

The pioneering of Paul unanimously resulted in Gospel proclamation. Luke’s common designation for gospel proclamation, “the word of the Lord,” appears 20 times between Acts 13 and 20 (13:5, 7, 44, 46, 48, 49; 14:3, 25; 15:7, 35, 36; 16:6, 32; 17:11,13; 18: 11; 19:10, 20; 20:32). Paul understood and taught others; the Gospel was the power of God unto salvation (Rom. 1:16). In his letters, Paul repeatedly expresses his compulsion to proclaim the Gospel (1 Cor. 9:16; Rom. 1:14-16; Gal. 1:11-12; Phil. 1:12-14; Acts 20:24). D.W.B. Robinson stated: “Paul cannot separate his own role from the operation of the gospel which he thus expounds as the gospel of hope and at the same time Paul’s apologia for his ‘priesthood’ in that gospel.”[45]

Paul’s gospel did not originate with man (Gal. 1:11-12), as he received, he also passed on as of first importance (1 Cor. 15:3-4). Across the Pauline corpus, perhaps no point is clearer than the content of Paul’s gospel. Faith in the gracious, atoning death, burial and resurrection of Jesus is the only source of salvation among men (Acts 13:27-39; 17:24-31; Rom. 3:21-26; 1 Cor. 15:1-5; Eph. 2:1-10; Phil. 2:6-11; Col. 1:15-23). Priority is also revealed in Paul’s emphasis on right response to the Gospel. In his farewell to the Ephesian elders Paul recounts his universal call for right response to the Gospel message. Acts 20:21 says, “I have declared to both Jews and Greeks that they must turn to God in repentance and have faith in the Lord Jesus.” The call for repentance, faith and recognition of Jesus as Lord is a consistent message across both Acts and Paul’s epistles (Acts 17:30; 20:21; 26:20; Rom. 2:4; 2 Cor. 7:9-10).

According to Romans 15:19, Paul’s proclamation of the Gospel was “fulfilled”. Commentators have debated the meaning of Paul’s assertion. Was Paul suggesting gospel saturation among the lost, or a presentation of the full gospel capable of ringing into every corner of the geography?[46] What is sure, Paul’s use of “pleroo” marks a definitive completion of his apostolic responsibility to the Gospel.[47]

In his farewell to the Ephesian elders, Paul recounts, “I consider my life worth nothing to me, my only aim is to finish the race and complete the task the Lord Jesus gave me—the task of testifying to the good news of God’s grace” (Acts 20:24). Paul’s aim had been “fulfilled” from Jerusalem to Illyricum. Paul’s conscience was clear. For three years, both publically and house to house, the gospel had been preached with integrity and would certainly accomplish the purposes of God (Acts 20:20, 31-32). For the Ephesian church leaders this meant they would never see his face again (20:25, 37-38). Pioneering work in Spain awaited (Rom. 15:28).

Priority #3 – Paul’s Mission sought the Obedience of the Gentiles.

Romans 15:18 says, “I will not venture to speak of anything expect what Christ has accomplished through me in leading the Gentiles to obey God by what I have said and done.”

Paul’s work was not simply proclamation. Paul prioritized disciple making resulting in the “obedience of the Gentiles.”[48] This work of disciple making was underway and bearing fruit, demonstrated in “word and deed” (Rom.15:18, NASB).[49]

Paul carries the theme of Gentile obedience throughout his letter to the Romans. In Romans 1:5 Paul begins with the statement, “Through him (Christ) we received grace and apostleship to call all the Gentiles to the obedience that comes from faith for his name’s sake”. O’Brien links “the obedience of faith” in Paul’s introduction (Rom.1:5) with his concluding remarks in 16:25-26. As a theme of mission, and therefore the Roman letter, the obedience of the Gentiles is found “at two highly significant positions in the letter, where it forms a frame or envelope (inclusio).” [50]

Romans 15:16 says Paul ministered “so that the Gentiles might become an offering acceptable to God, sanctified by the Holy Spirit.” In verse 18 Paul cites the “obedience of the Gentiles” as evidence the work of sanctification was underway. O’Brien quotes D. B. Garlington who argued the obedience of the Gentiles was more than just “believing acceptance”, but also their “constancy of Christian conduct.”[51] In several cases, Paul revisited areas of previous persecution in order to invest in disciple making (Acts 14:20, 22; 16:40; 18:9-10; 20:1). In his letters to various churches Paul consistently relates his desire for maturity among them (Phil. 1:9-11; Col. 1:9-14, 22; 1 Thess. 3:12-13; 2 Thess. 2:13-17).

In the original language, verse 18 carries some ambiguity as to whose “word and deed” is referenced. The NASB has rendered the text, “I will not presume to speak of anything except what Christ has accomplished through me, resulting in the obedience of the Gentiles by word and deed.” Was “word and deed” a reference to Paul’s teaching and practice among the Gentiles,[52] or were the Gentiles reproducing Paul’s teaching and practice in their obedience.[53] Either way, the teaching and example of Paul resulted in observed obedience.[54] This obedience was the fruit of repentance and faith (Acts 26:20). By these means Paul was assured discipleship, toward sanctification was underway (Phil. 1:6; 1 Cor. 1:5-9).

Priority #4 – Paul’s Mission resulted in New Churches

Romans 15:20 says, “It has always been my ambition to preach the gospel where Christ was not known, so that I may not be building on someone else’s foundation.”

Paul prioritized the formation of churches (foundation laying) throughout his ministry (Acts 14:23; 1 Cor. 3:9-11; Eph. 3:7-11; 1 Thess. 2:17-3:13; Titus 1:5). He also included concern for church formation in the description of his assignment (Col. 1:24-2:7; Rom. 1:1-15; 15:14-16). Robert Banks has suggested, “Its (Paul’s mission) purpose is first the preaching of the gospel and the founding of churches, and then the provision of assistance so that they may reach maturity.”[55]

While speaking of himself and Apollos in 1 Cor. 3:9-11 Paul says, “For we are co-workers in God’s service; you are God’s field, God’s building. By the grace God has given me, I laid a foundation as a wise builder, and someone else is building on it. But each one should build with care. For no one can lay a foundation other than the one already laid, which is Jesus Christ.”Empowered by God (v.6), co-workers (v. 9) must do this “work” (v. 13, 13b, 14, 15). The result of the “work” is an established church which authenticates the missionary task (1 Cor. 9:1-2; 2 Cor. 3:1-3).[56]

In examining Paul’s Romans 15 summary we find the link to Acts 20:3 helpful. Every church credited to Paul as the “planter” had been established by Acts 20:3.[57] Thomas Schreiner summarizes, “Paul had systematically planted churches in strategic centers so that Gentiles who had not yet heard the gospel would now hear it proclaimed. Paul presumably feels that no further work awaits him in the east because the foundation has been laid there. By establishing churches in strategic centers from Jerusalem to Illyricum, the base has been laid, and Paul leaves to others the task of moving from these centers to the hinterlands.”[58]

Paul’s role among the churches he founded included the recognition of local Elders. Paul went to great lengths to ensure, no flock was left without a shepherd (Acts 14:23). Paul’s commissioning of the Ephesian Elders (Acts 20:17-35) offers a summary of apostolic responsibility in the development of local church leadership.[59] Here elders (v. 17), made “overseers” by the Lord (v.28) are told to “shepherd the church of God” (v.28). It is clear these leaders were local and distinct from Paul’s travel companions (v.13-17). The integrity with which Paul taught, modeled and commissioned local leaders and churches he planted allowed him to be “innocent of their blood” (v.26). Despite future challenges (v. 29-31), Paul could commit the elders to “God and the word of his grace” with assurance of the Spirit’s ongoing care resulting in “an inheritance among all those who are sanctified” (v. 32).

Priority #5 – Paul’s Mission was multiplied through “Co-Workers”.

Acts 20:4, “He was accompanied by Sopater son of Pyrrhus from Berea, Aristarchus and Secundus from Thessalonica, Gaius from Derbe, Timothy also, and Tychicus and Trophimus from the province of Asia.”

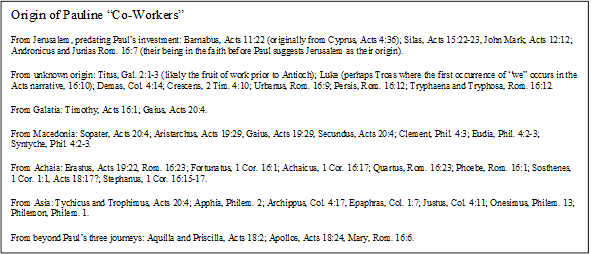

Finally, Paul expected his role in “the work” would be multiplied by co-workers. Approximately one hundred names are connected with Paul in the New Testament. Eckhard Schnabel has determined, “thirty eight are coworkers of the apostle.”[60]

Interestingly, neither the thirty eight coworkers nor any of the nearly 100 names associated with Paul were ever given the title elder, overseer or shepherd.[61] This is not to say these roles were not Paul’s priority. As it has already been shown Paul went to great lengths, even risking further persecution in areas previously hostile in order to recognize local leaders among new churches (Acts 14:23). The point here is coworkers of Paul were of a different sort than those tasked with formal, ongoing oversight of local churches. Distinguished from the elders appointed within the early Galatian ministry (Acts 14:23), and the “Elders of Ephesus” (Acts 20:17), Paul’s coworkers are seen itinerating with Paul in fulfillment of various apostolic roles. Interestingly, the majority of these coworkers came from the churches Paul had planted.[62]

Above we see twenty-four of Paul’s coworkers originating from the church planting fields where Paul labored. This suggests the churches established by Paul were expected to participate in the sending of apostolic coworkers where Paul had need (1 Cor. 16:17; Phil. 2:30).[63] Schnabel writes, “The coworkers who accompanied Paul on his travels participated in his missionary activities and can thus be seen as trainees, much like Jesus’ disciples who had been chosen by Jesus to be with him (Mk 3:13-15) and to be trained as ‘fishers of people (Mk 1:17).”[64] It is also worth noting, as distinguished from elder/overseers, several of these were women: Priscilla, Apphia, Euodia, Junias, Persis, Phoebe, Tryphaena and Tryphosa.[65]

When speaking of Paul’s co-workers, Banks reports, “No where do we find any hint of the ‘body’ metaphor, so frequently used of the church, being applied to this group.” Banks believes Paul’s “co-workers” were more involved in a common task (ergon) than a common life (Gal. 6:4, 1 Cor. 3:13-15, 9:1, 16:10, Phil. 2:30).[66] Banks concludes, “Paul’s mission is a grouping of specialists identified by their gifts, backed up by a set of sponsoring families and communities, with a specific function and structure. . . . Paul’s work is essentially a service organization whose members have personal, not structural, links with the communities and seek to develop rather than dominate or regulate.”[67]

If the coworkers of Paul were not the elder/overseers of the churches they came from or that they founded, who were they? Eckhard Schnabel has suggested they were, “new missionaries” in training.[68] Schnabel concludes they were “just like Paul himself – the servants, slaves and helpers of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ.” The most common term among Paul’s companions was “ergates”, literally “worker” or “synergos”, “coworker”.[69] These were men and women who shared fully in the apostolic task of pioneering, evangelizing, disciple making and the planting and strengthening of new churches.[70]

As Paul visits the Corinthians for the presumably, last time he is not alone (Acts 20:3-4).[71] Acts 20:4 offers the most extensive list of Pauline companions recorded in Acts. While these coworkers are associated with the offering for Jerusalem,[72] the names of several Pauline co-workers are included. At the terminus of Paul’s third missionary journey, Luke takes time to record not only the names of Paul’s coworkers, but also their place of origin. When coupled with the list of Corinthians in Rom. 16:21-23 this gathering in Corinth included representatives of every province where churches had been planted (Acts 13-20).[73]

The three months in Corinth (Acts 20:3) included a gathering of teamed, cross-pollinated “workers” capable of carrying on strategic priorities in each province.[74] The Acts 20:4 gathering further assured Paul his “work” was “fulfilled” in the form of coworkers capable of the multiplying the “work” beyond Paul’s previous reach.[75]

No Place Left: Promised therefore Possible

Two thousand years ago, the Spirit of God used Paul to reveal His strategic priority for mission. These priorities are essential to the completion of the Great Commission (Mt. 28:18-20, Acts 1:8).

Paul faced tremendous challenges in his 1st century context including Paganism, Hellenistic philosophies, the dangers of syncretism, not to mention persecution at a level rarely reported since. The dangers of Paul’s travel by foot and ship can hardly be estimated in our 21st century (2 Cor. 11:23-27). Paul did not have access to 21st century modes of transport, missiological research, media tools or even its literacy rates.

What Paul had was the Holy Spirit and the Word of God. These were enough to offer him a clear conscience where the foundation had been laid (Acts 20:32). By the Spirit’s power Paul pioneered, proclaimed, discipled and formed churches complete with local elder/overseers. From the harvest, the Spirit raised up co-workers Paul both recruited and trained to carry on the work of turning the world upside down (Acts 17:6). This is mission. These are the “strategic priorities” recorded in scripture. By the exercise of these priorities, Paul fulfilled the work in his generation. His example is both inspiration and model for the church in all times.

One hundred years ago, Roland Allen said, “In no other work do we set the great masters wholly on one side, and teach the students of today that whatever they may copy, they may not copy them. “Either we must drag down St Paul from his pedestal as the great missionary, or else we must acknowledge that there is in his work that quality of universality.”[76]

Our confidence is not in a man or his strategy. Rather we are confident in the Spirit of God who continues to initiate, authorize, direct and empower. By the power of the Spirit, after the example of the “missionary to the Gentiles” we must pioneer, proclaim, disciple, form churches and multiply coworkers until there is “no place left”. By the power of the Spirit, a generation aligned with His priorities will fulfill His Great Commission. That generation is coming. Perhaps they are among us even now.

Bibliography:

Addison, Stephen B. “A Basis for the Continuing Ministry of The Apostle in the Church’s

Mission.” D-Min diss., Fuller Theological Seminary, 1996.

Allen, Roland. Missionary Methods: St Paul’s or Ours. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1962.

Banks, Robert. Paul’s Idea of Community. rev. ed. Peabody Mass: Hendrickson, 1994.

Barnett, Mike. “The Global Century.” In Discovering the Mission of God: Best Missional

Practices for the 21st Century. Edited by Mike Barnett. 287-306. Downers Grove, Ill: IVP

Academic, 2012.

Bosch, David J. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shift in Theology of Mission. Maryknoll NY:

Orbis, 1991.

Bowers, Paul. “Fulfilling the Gospel: The Scope of the Pauline Mission”, JETS, 30, 2 (June,

1987) 185-198.

Bruce, F.F. The Spreading Flame: The Rise of Christianity from Its First Beginnings to the

Conversion of the English. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1958.

Dent, Don. The Ongoing Role of Apostles in Mission: The Forgotten Foundation. Bloomington

Ill: Crossbooks, 2011.

Fee, Gordon D. Paul, the Spirit, and the People of God. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1996.

George, Timothy and Denise. John A. Braodus: Baptist Covenants, Confessions and Catechisms. Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 1999.

Green, Michael. Evangelism in the Early Church, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970.

----- “Evangelism in the Early Church.” In Let the Earth Hear his Voice, edited by J.D. Douglas, Minneapolis: World Wide, 1975.

Guthrie, Stan. Missions in the Third Millennium: 21 Key Trends for the 21st Century. Milton

Keynes, UK: Paternoster, 2000.

Haney, Jim. “The State of the Spread of the Gospel.” In Discovering the Mission of God: Best

Missional Practices for the 21st Century, edited by. Mike Barnett. 309-322. Downers

Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2012.

Harnack, Adolf. The Mission and Expansion of Christianity in the First Three Centuries. New

York: Harper & Brothers, 1961.

Hedlund, Roger E. The Mission of the Church in the World. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1985.

Hesselgrave, David J. Paradigms in Conflict: 10 Key Questions in Christian Missions Today. Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic, 2005.

----- Planting Cross Culturally: North America and Beyond. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2000.

Jenkins, Phillip. The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity. New York: Oxford

University Press, 2002.

Johnstone, Patrick. The Church Is Bigger Than You Think. Fearn, UK: Christian Focus Publications/WEC, 1998.

Kane, Herbert J. Christian Missions in Biblical Perspective. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1976.

Kostenberger, Andreas J. “Women in the Pauline Mission,” In The Gospel to the Nations:

Perspectives on the Pauline Mission, Edited by P. Bolt and M. Thompson. Leicester,

U.K.: Inter-Varsity Press, 2000.

Kostenberger, Andreas J. and Peter T. O’Brien. Salvation to the Ends of the Earth: A Biblical

Theology of Mission. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2001.

Latourette, Kenneth Scott. A History of Christianity. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1953.

----- “The Light of History on Current Missionary Methods.” International Review of Missions, 42, no. 166 (April): 137-143.

McRay, John. Paul: His Life and Teaching. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2003.

O’Brien, P.T. Gospel and Mission in the Writings of Paul: An Exegetical and Theological Analysis. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1995.

Payne, J.D. Apostolic Church Planting: Birthing New Churches from New Believers. Downers

Grove: InterVarsity, 2015.

----- Discovering Church Planting: An Introduction to the Whats, Whys, and Hows of

Global Church Planting. Colorado Springs: Paternoster, 2009.

Plummer, Robert and John Mark Terry, Paul’s Missionary Methods: In His Time and Ours.

Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2012.

Polhill, John. B. Paul and His Letters. Nashville: B&H, 1999.

----- The New International Commentary: Acts, vol. 26. Nashville: B&H Publishing, 1992.

Robinson, D.W.B. “The Priesthood of Paul in the Gospel of Hope”, In Atonement and

Eschatology presented to L.L. Morris on is 60th Birthday, edited by R.J. Banks, Exeter: Paternoster, 1974.

Schnabel, Eckhard J. Early Christian Mission: Paul and the Early Church, vol. 2. Downers

Grove: InterVarsity, 2004.

----- Paul the Missionary: Realities, Strategies and Methods. Downers Grove

Ill: IVP Academic, 2008.

Schreiner, Thomas R. Paul: Apostle of God’s Glory in Christ. Secunderabad: OM Books, 2001.

Snodgrass, J. "To Teach Others Also: An Apostolic Approach to Theological Education.” PhD

Diss., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, forthcoming.

Stark, Rodney. The Triumph of Christianity. New York: Harper Collins, 2011.

Stott, John. Making Christ Known: Historic Mission Documents from the Lausanne Movement

1974-1989. Carlisle CA: Paternoster, 1996.

----- The Message of Acts. Leicester: Inter Varsity, 1990.