A review of the literature on ��ethnicity�� and ��national identity��

and related missiological studies

Enoch Wan

and Mark Vanderwerf

Published in www.GlobalMissiology.org ��Featured Articles�� April, 2009

I.

Introduction

In this study, the review the literature will focus on publications on the theoretical background of ��ethnicity�� and ��national identity�� and related missiological studies.

II.

A Review of

the Literature on ��ethnicity�� and ��national identity��

Professor Adrian Hastings' comments are especially relevant for Bosnia-Herzegovina,

Ethnicity, nation, nationalism and religion are four distinct and determinative elements within European and world history. Not one of these can be safely marginalized by either the historian or the politician concerned to understand the shaping of modern society. These four are, moreover, so intimately linked that it is impossible, I would maintain, to write the history of any of them at all adequately without at least a fair amount of discussion of the other three.[1]

A clear definition of the key-terms is important because authors use them in different ways. In this section we shall review the literature on these background concepts and then examine the literature on related topics.

1.. Ethnicity

The most common approach in the literature is to begin with ethnic groups and see ethnicity as emerging from one's relationship to a particular ethnic group. The respected Canadian scholar Wsevolod Isajiw argues for this approach,

First of all, the meaning of the concept of ethnicity depends on the meaning of several other concepts, particularly those of ethnic group and ethnic identity. The concept of ethnic group is the most basic, from which the others are derivative.[2]

We find this approach problematic, since beginning with the ethnic group itself opens the door to reifying that ethnic group and turning an abstract concept into an objective entity with the power to act collectively. This pushes the researcher, often unconsciously, toward a primordialist understanding of ethnicity.

It is more helpful, we believe, to begin with ethnicity itself, viewing it as a sense of solidarity shared between people (usually related through real or fictive kinship) who see themselves as distinct and different from others.[3] The plan is to begin with ��ethnicity,�� then onto ��ethnic identity,�� then to ��ethnic community.�� In adopting this approach and seeing "ethnicity is essentially an aspect of a relationship, not the property of a group,"[4] yet recognizing the foundational role of kinship, we are following what John Comaroff has described as a new consensus that seems to be emerging in the study of ethnicity -- a position that "tempers primordialism with a careful measure of constructionism."[5]

A. Defining ethnicity

In our review of the literature, the best overview of the history and meaning of the concept of ��ethnicity�� and the related term ��race�� was in Cornell and Hartmann's book Ethnicity and Race.[6] The term ��ethnicity�� itself is relatively recent.[7] Prior to the 1970s there was little mention of it in anthropological literature and textbooks contained no definitions of the term.[8] Before World War II, the term "tribe" was the term of choice for "pre-modern" societies and "race" for modern societies.[9] Due to the close link between the term "race" and Nazi ideology, the term "ethnicity" gradually replaced "race" within both the Anglo-American tradition and the European tradition.[10] Discussion of ethnicity is complicated by the variety of related terms used to designate similar phenomena, such as race, tribe, nation and minority group.[11] Some scholars use these terms interchangeably while others treat them as unrelated concepts.

The term ��ethnicity�� is used in many ways. Siniša Malešević comments on the "slippery nature of ethnic relations and the inherent ambiguity of the concept of ethnicity�K Such a plasticity and ambiguity of the concept allows for deep misunderstandings as well as political misuses."[12] Jack David Eller agrees, "Some of the most perplexing problems arise from the vagueness of the term and phenomenon called ethnicity and from its indefinite and ever-expanding domain."[13]

The relationship between ethnicity and race is complex. While there is much overlap they are distinct concepts. Pierre van den Berghe describes "race as a special marker of ethnicity" that uses biological characteristics as an ethnic marker. [14] While the relationship between the two concepts is more complex than that, his generalization points in the right direction. In this study, race is not an issue since there is little or no phenotypical difference between the main national or ethnic groups of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Most Americans, when they hear the term "ethnic" immediately think of "minority groups," like African-Americans, Vietnamese, or Hispanics. It reminds them of "a people outside of, alien to, and different from the core population."[15] The term minority group refers to a sociological group, such as an ethnic group, that does not constitute a politically dominant plurality of the total population of a given society. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, each of the main national groups is a majority group in certain geographic regions of the country, and a minority group in others.

British scholars, like their American counterparts, typically ascribe ethnicity only to minority groups in a society. Ethnic groups are defined as "a distinct collective group" of the population within the larger society whose culture is different from the mainstream culture. Cashmore��s recent article on "ethnicity" in the Encyclopedia of Race and Ethnic Studies, follows this approach, defining an "ethnic group" as,

The creative response of a people who feel somehow marginal to the mainstream of society.[16]

This shows up in the Webster's definition of "ethnic,"

A member of an ethnic group; especially : a member of a minority group who retains the customs, language, or social views of the group."[17]

In the European tradition, however, ethnicity is understood not as a synonym for minority groups, but as a synonym for "nationhood" or "peoplehood".[18] In this tradition, everyone, not just minorities, belong to an "ethnic group." In this study I follow the European usage of the term.

A variety of definitions of ethnicity have been suggested.[19] The classic definition is that of Glazer and Moynihan, "the condition of belonging to a particular ethnic group."[20] Cashmore's definition, while more "modern," is similar,

The salient feature of a group that regards itself as in some sense (usually, in many senses) distinct�K Once the consciousness of being part of an ethnic group is created, it takes on a self-perpetuating quality and is passed from one generation to the next.[21]

Rogers Brubaker suggests an alternative approach, emerging from the relatively new discipline of cognitive anthropology,[22] that he calls "ethnicity without groups." In this approach, ethnicity is essentially a "way of seeing" the social world around us and "categorizing" ourselves and others within that world. His suggestion fits well with the phenomena of ethnicity as it exists in Bosnia-Herzegovina,

To understand how ethnicity works, it may help to begin not with "the Romanians" and "the Hungarians" as groups [here we could just as easily substitute the Croats, the Serbs, and the Bosniaks], but with "Romanian" and "Hungarian" as categories. Doing so suggests a different set of questions than those that come to mind when we begin with "groups." Starting with groups, one is led to ask what groups want, demand, or aspire towards; how they think of themselves and others; and how they act in relation to other groups. One is led almost automatically by the substantialist language to attribute identity, agency, interests, and will to groups. Starting with categories, by contrast, invites us to focus on processes and relations rather than substances. It invites us to specify how people and organizations do things with, and to, ethnic and national categories; how such categories are used to channel and organize processes and relationships; and how categories get institutionalized and with what consequences.[23]

Brubaker��s approach allows the researcher to integrate insights from most of the major theories of ethnicity, rather than treating them as mutually exclusive,

The classic debate [is] between primordialist and circumstantialist or instrumentalists approaches�K Cognitive perspectives allow us to recast both positions and to see them as complementary rather than mutually exclusive... rather than contradicting one another, they can be seen as directed largely to different questions.[24]

B. Theories of ��ethnicity��

Definitions of ��ethnicity�� emerge out of specific anthropological and sociological theories.[25] When reading books on ethnicity, and books on Bosnia-Herzegovina, readers would be helped by first investigating which theory of ethnicity the author of a given book holds since it strongly affects the author's perspective and conclusion.

Anthropological theories of ethnicity can be grouped into three basic categories: Primordialist theories, Instrumentalist theories, and Constructivist theories (see Table 1).[26] These theories broadly reflect changes of approach in anthropology over the past 20 years, i.e. the shift from cultural evolution theories, to structural-functional theories, to conflict theories, and finally to postmodern theories.[27]

Table 1 - Three Basic Approaches to Understanding Ethnicity

|

Perspective |

Description |

|

Primordialist

Theories |

Ethnicity

is fixed at birth. Ethnic

identification is based on deep, ��primordial�� attachments to a group or

culture. |

|

Instrumental

Theories |

Ethnicity, based on people's "historical" and "symbolic" memory, is something created and used and exploited by leaders and others in the pragmatic pursuit of their own interests. |

|

Constructivist

Theories |

Ethnic identity is not something people "possess" but

something they "construct" in specific social and historical

contexts to further their own interests. It is therefore fluid and subjective. |

|

|

|

These changes are related to the twin forces of modernity and globalization. Globalization started as an economic phenomenon and end up as a phenomenon of identity. Traditional ways people defined who they were have been undermined.[28] Modernity has,

Remade life in such a way that "the past is stripped away, place loses its significance, community loses its hold, objective moral norms vanish, and what remains is simply the self."[29]

The result of this

process has been a loss of identity resulting in fragmentation and rootlessness

(anomie) at the personal level and

the blurring of identities at the collective level. This in turn led to more fluid

understandings of ethnicity.

Eriksen comments,

Recent debates in anthropology and neighbouring disciplines pull in the same direction: away from notions of integrated societies or cultures towards a vision of a more fragmented, paradoxical and ambiguous world. In anthropology at least, the recent shift towards the study of identities rather than cultures has entailed an intense focus on conscious agency and reflexivity; and for many anthropologists, essentialism and primordialism appear as dated as pre-Darwinian biology.[30]

a. Primordialist

theories of ethnicity.

This perspective was popular until the mid-1970s. Primordialism is an "objectivist

theory" or "essentialist theory" which argues that "ultimately

there is some real, tangible, foundation for ethnic identification."[31] Isajiw writes,

The primordialist approach is the oldest in sociological and

anthropological literature. It argues that ethnicity is something given,

ascribed at birth, deriving from the kin-and-clan-structure of human society,

and hence something more or less fixed and permanent.[32]

The two crucial factors in a primordialist perspective are highlighted in his quote: a) one��s ethnicity is ascribed at birth and b) one��s ethnicity is more or less fixed and permanent.

Primordialist theories view human society as a conglomeration of distinct social groups. At birth a person "becomes" a member of a particular group. Ethnic identification is based on deep, ��primordial�� attachments to that group, established by kinship and descent. One��s ethnicity is thus "fixed" and an unchangeable part of one��s identity.

The roots of primordialist thinking can be traced back to the German Romantic philosophers, especially J.H. Herder. He argued for the "atavistic power" of the blood and soil (Blut und Boden) that bound one closely with one��s people (das Volk).[33]

No major scholar today holds to classical primordialism. Contemporary primordialists can be subdivided into two groups - those who see primordial ties to a group as a biological phenomenon[34] (socio-biological primordaism) and those who see it as a product of culture, history, and/or foundational myths, symbols and memories (ethnosymbolism). The key point is that these primordial ties to one's group are fixed and generally do not change over the course of a person's lifetime.

The most prolific writer in the field of ethnicity and nationalism is Anthony D. Smith, Professor of Ethnicity and Nationalism at the London School of Economics. His perspective (what he now calls ethnosymbolism) is a "soft" form of primordialism. He views the defining elements of ethnic identification as psychological and emotional, emerging from a person��s historical and cultural background,

The ��core�� of ethnicity resides in the myths, memories, values, symbols and the characteristic styles of particular historic configurations. He [Smith] emphasizes what he calls a myth-symbol complex and the mythomoteur, which is the constitutive myth of the ethnic commonalty. Together these two form the body of beliefs and sentiments, which the defenders of the ethnie wish to preserve and pass on to future generations. The durability of the ethnie resides in the forms and content of the myth-symbol complex. Of pivotal importance for the survival of the ethnie is the diffusion and transmission of the myth-symbol complex to its unit of population and its future generations.[35]

Smith emphasizes the "extraordinary persistence and resilience of ethnic ties and sentiments, once formed"[36] and argues that they are essentially primordial since they are received through ethnic socialization into one��s ethnie and are more or less fixed. [37]

b. Fredrick Barth��s paradigm changing essay.

A major paradigm change in the understanding of ethnicity occurred following the publication of Norwegian anthropologist Fredrick Barth's famous 1969 article, "Ethnic Groups and Boundaries."[38] In that essay he questioned the belief that "the social world was made up of distinct named groups" and argued that the identity of the group was not a "quality of the container" (i.e. an "essence" or a fixed, objective reality belonging to a cultural or ethnic group) but what emerges when a given social group interacts with other social groups.

The interaction itself highlights differences between the groups and these cultural differences result in the formation of boundaries distinguishing "us" from "them." "A group maintains its identity," he wrote, "when members interact with others." Ethnicity, Barth insisted, is based on one��s perception of "us" and "them" and not on objective reality that actually exits "out there" in the real world. Markers, such as language, religion, or rituals serve to identify these subjective ethnic "boundaries." Since these can change, ethnicity is not fixed but situational and subjective.[39] He believed the focus should be placed on the "boundaries" between groups, not on the groups themselves. It was there, at these "boundaries" that ethnicity was "constructed." By separating ethnicity from culture, Barth made ethnicity an ever changing, socially constructed, subjective construct.[40] In a self-evaluation in 1994, Barth considered himself to have anticipated Postmodernism.[41]

Under Barth��s influence, anthropologists "shifted the anthropological emphasis from the static evocation of tribal identity as a feature of social structure to a recognition of ethnic identity as a dynamic aspect of social organization." This eventually became the "basic anthropological model of ethnicity."[42] From this emerged instrumental and social constructionist theories of ethnicity.

c. Instrumentalist theories of ethnicity.

Proponents of instrumentalist theories view ethnicity as something that can be changed, constructed or even manipulated to gain specific political and/or economic ends.[43] Elite theory, which argues that the leaders in a modern state (the elite) use and manipulate perceptions of ethnic identity to further their own ends and stay in power is an approach advocated by scholars Abner Cohen, Paul Brass and Ted Gurr,

Ethnicity is created in the dynamics of elite competition within the boundaries determined by political and economic realities" and ethnic groups are to be seen as a product of political myths, created and manipulated by culture elites in their pursuit of advantages and power.[44]

In his anthropological research on New York Chinatown, Enoch Wan has found that the ��Chinese ethnicity�� of this immigrant community is circumstantial, flexible, fluid and instrumental.[45]

d. Postmodern and constructionist theories of ethnicity.

Isaijw describes this group of theories like this,

Theoretically, this approach lies somewhere between Michel Foucault's emphasis on construction of the metaphor and Pierre Bourdieu's notions of practice and habitus as the basic factors shaping the structure of all social phenomena. The basic notion in this approach is that ethnicity is something that is being negotiated and constructed in everyday living. Ethnicity is a process which continues to unfold.[46]

Postmodern theories are concerned more with nations and nationalism than with ethnicity and will be explored in more detail in that section of the literature review. With the rise of the postmodern paradigm, attention shifted to the issue of group boundaries and identity. Scholars operating in this paradigm felt that terms like "group," "category" and "boundary" connotate a fixed identity, something they wanted to avoid. This has resulted in much confusion as various interest groups are now exploiting the elastic nature of the term ethnicity,

When is a group an ethnic group? There are no hard-and-fast rules or standards by which to judge. The answer, as unsatisfying as it is, is that social collectivity, of any nature and antiquity, can don the mantle of ethnicity�Xone of the most elastic of social concepts�Xand stake a successful claim to identity and rights as a group. The point is this: it does not matter if any particular group is "really" an ethnic group, or what a "real" ethnic group is; instead, ethnicity has become so central to social discourse�Xand social competition�Xthat its salience and effectiveness have become attractive to all sorts of collectivities.[47]

2. Nation

One of the most influential doctrines in modern history is that all humans are divided into groups called nations.[48] This understanding provides the starting point for the ideology of nationalism. While the term "nation" came from the Latin term natio and originally described the grouping of students in a college speaking the same language, in his survey of the history of the term Hastings argues that the ideal of a nation‑state and of the world as a society of nations entered the western world through the mirror of the Bible, Europe��s primary textbook,

No other book had half so wide or pervasive an influence in

medieval

In the Vulgate Bible,

A. Basic issues

According to Smith three issues and the debates they have engendered reoccur continually in discussions of nations and nationalism,

The first is ethical and

philosophical�K Should we regard the nation as an end in itself�K or understand

the nation and national identity as a means to other ends and values? �K

The second is anthropological and

political. It concerns the social

definition of the nation. What kind

of community is the nation and what is the relationship of the individual to

the community? Is the nation

fundamentally ethno-cultural in character, a community of (real or fictive)

descent whose members are bound together from birth by kinship ties, common

history and shared language? Or is it largely a social and political community

based on common territory and residence, on citizenship rights and common laws?

The third is historical and sociological. It concerns the place of the nation in the history of humanity. Should we regard the nation as an immemorial and evolving community rooted in a long history of shared ties and culture. Or are nations to be treated as recent social constructs or cultural artifacts, at once bounded and malleable, typical product of a certain stage of history and the special conditions of a modern epoch, and hence destined to pass away when that stage has been surpassed and its conditions no longer apply? [50]

Of these three grouping of debated issues, the second set (anthropological and political) is the one of particular importance to this study.

B. Theories

Theories of the origins of nations can be

grouped into four basic categories (see Table

2).

a. Nationalist theories.

The first basic theory is called the "Nationalist" theory. Modern nation-states are seen as direct descendants of ancient primordial ethnic groups. [51] The theoretical underpinnings of this approach rest on a primordialistic view of ethnicity. This is the position of Croatian and Serbian nationalist historians.

b. Pernnialist theories.

Anthony D. Smith, probably the most prolific writer on nationalism, proposed a view known as "perennialism." This group of theories sees ethnic groups as stable, even ancient units of social cohesion. The first European nations were formed out of pre-modern ethnic cores. Smith labels these ethnie, a collective group that falls between ethnic groups and nations,

We may list six main attributes of ethnic community (or ethnie, to use the French term): 1) a collective proper name 2) a myth of common ancestry 3) shared historical memories 4) one or more differentiating elements of common culture 5) an association with a specific 'homeland' and 6) a sense of solidarity for significant sectors of the population.[52]

Before the rise of nation-states, citizens owed loyalty to

the ruling dynasty. The focus of

most people was local, centered on their clan, tribe, village or region. With the rise of communication and

education, knowledge of history and current events expanded beyond one's local

community and people began to develop a feeling of a collective cultural

identity with others who spoke their language and practiced their

religion. This growing sense of

collective identity led to the emergence of nation-states.

In contrast to an ethnic groups, a nation is a far more

self-conscious community than an ethnicity�K [It] is normally identified by a

literature of its own, it possesses or claims the right to political identity

and autonomy as a people, together with the control of specific territory,

comparable to that of biblical

Nations, therefore, at least in the common western understanding

of the term, first emerged in

The movement, therefore, is from "ethnic group," to "ethnie" to "nation" to nation-state. Not all ethnic groups become ethnie, not all ethnie become "nations" and not all nations are "state-forming nations" (državnotvorni narodi). Smith saw ethnic unity is a necessary condition for the national survival and unity. He traced this necessary ethnic unity to the existence of coherent mythology, and a symbolism of history and culture in an ethnic community. It is difficult, if not impossible, he argued, for an ethnic community to become a nation-state without these ethno-symbolic factors. This is why, he concluded, the ethnic groups in Communist Yugoslavia, while speaking a common language, did not develop a Yugoslav national identity. [55]

Table 2 �V The Four Basic Theories of the Origins of Nations [56]

|

Theory |

Description |

|

Nationalist |

Nations

have existed as long as man has existed.

It is part of being human to seek to form nations. |

|

Pernnialist theories |

Nations have been around for a long time, but have taken different

shapes at different points in history.

National forms may change and particular nations may dissolve, but the

identity of a nation is unchanging.

The past (history) is of great importance. (Anthony D. Smith) |

|

Modernist theories |

Nations are entirely modern and are socially constructed. The past is largely irrelevant. The

nation is a modern phenomenon and socially constructed, the product of

nationalist ideologies, which themselves are the expression of modern,

industrial society. This is

currently the most prevalent

scholarly position (Ernest Gellner) |

|

Post-modern |

While nations are modern and the product of modern cultural

conditions, modem nationalist leaders (elites) "use" the past for

their own ends �V i.e. they select, invent and mix traditions from the ethnic

past and offer them as justification for their actions. The present creates the past in its

own image. |

|

|

|

Milton Esman offers a more nuanced explanation. He distinguishes between an "ethnic community" and an "ethnic nation." An ethnic community is "a group of people united by inherited culture, racial features, belief systems (religions), or national sentiments."[57] Membership in such a community is usually ascribed, i.e. a person is born into an ethnic community. He describes an "ethnic nation" as,

A politicized ethnic community whose spokesmen demand control over what they define as their territorial homeland�K a people which demands or actively exercises the right to self-determination �V political control within their homeland.[58]

Such aspirations, he notes, can eventually lead to ethnic violence and disintegration of multiethnic states. His approach accurately describes the situation in post-Dayton Bosnia-Herzegovina.[59]

c. Modernist theories.

The two other basic positions, "modernist" and "postmodernist," view "nations" as modern, essentially artificial constructs. Ernest Gellner (Smith's former teacher) was the leading proponent of "modernism." In his classic work, Nations and Nationalism (1983), Gellner argued that both nations and nationalism are essentially modern phenomena that emerged after the French Revolution as a result of modern conditions such as industrialism, literacy, education systems, mass communications, secularism and capitalism. Nationalism, he argues, is "new form of social organisation, that is based on deeply internalised, education-dependent high cultures each protected by its own state."[60] Gellner's unapologetic positivism is out of kilter with the postmodern "zeitgeist" in British and North American anthropology but not Central and Eastern European sociology, where his work commands wider respect."[61] Bellamy summarizes the basic difference between Gellner and Smith,

The 'great debate' in nationalism studies is between so-called 'primordialists' and 'modernists.' Put simply, primordialists argue that the nation derives directly from a priori ethnic groups and is based on kinship ties and ancient heritage. For their part, modernists insist that the nation is an entirely novel form of identity and political organization, which owes nothing to ethnic heritage and everything to the modern dynamics of industrial capitalism.[62]

d. Post-Modern theories.

Benedict Anderson is the most well-known proponent of the postmodernist perspective on nations. His definition of "nation" is probably the most widely quoted definitions of a "nation" by modern scholars,

In an anthropological spirit, then, I propose the following definition of the nation: it is an imagined political community - - and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign.. all communities larger than primordial villages of face-to-face contact (and perhaps even these) are imagined. Communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity or genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined.[63]

3. Nationalism

In everyday usage, the term "nationalism" is

used to describe an emotional attachment to one's nation. In the scholarly literature, however,

the term has a specialized meaning.

Spencer provides a classic definition of nationalism in the Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural

Anthropology,

Nationalism is the modern ideology that humanity can be divided into separate, discrete units (nations or peoples) and that each nation should constitute a separate political unity (a state).[64]

Sometimes this is referred to as "nation-state theory." Nation-states are thought to have an inherent right to create their own laws and develop and support their own institutions for the realization of social, economic, and cultural aspirations of their people. Spencer comments,

This assumption is so widespread in the modern world that it has rarely been subjected to sustained intellectual scrutiny. The great social theorists like Weber and Marx often treated nationalism, and the vision of human cultural difference on which it is based, as a self-evident feature of the world.[65]

This theory emerged in the nineteenth century and was

built on an assumption that "nations" (races) have an inherent right

to govern themselves (self-determination).

As an ideology nationalism links a primordialist

understanding of ethnicity with the doctrine of

"self-determination." It

is generally argued that "a powerful link exists between romanticism and

nationalism... Nationalism is the political expression of romanticism."[66] Nation-state theory was later canonized

by President Woodrow Wilson and the

"Nationalism," writes

The claim that one's own group has certain rights that are superior to those of others, perhaps in some sense transcendent, and that one's own group is entitled to set the rules for members of other groups to follow within a certain territory, or to assert territorial autonomy within specified boundaries.[68]

Nationalism elevates collective rights of a national group

in a state at the expense of individual rights. In extreme cases, whatever furthers the

interest of the national group is morally right,

An appeal to "collective rights" serves to justify �K notions that violence against group "outsiders" is morally justified (as in the case of "ethnic cleansing"); claims of a right to take house from "another nation" to redress losses by one's "own nation," demands for territorial and local autonomy; assertions of a right to secede, even against the wishes of the numerical majority (as claimed by the Bosnian Serbs in 1992) and equations of the nation with the state.[69]

In practice, such an approach makes "second class citizens" out of every who is of a different ethnic or national heritage or who does not condone the authoritarian approach of nationalistic leaders,

Underlying the assertion of the doctrine of collective rights is the demand for conformity �V the demand that all persons within a certain territory speak the same language, believe the same things, worship the same God, observe the same customs, and, ideally, identify with the same collective construction ("We are all Serbs here" or "We are all Muslims here"). [70]

In practice, the theory of nationalism can become a powerful motivator for large collectivities of people who see themselves as part of an ethnic or national group that does not have the nation-state they believe they have a "right" to. It motivates people because of,

Its underlying conviction "that one��s own ethnic or national tradition is especially valuable and needs to be defended at almost any cost through creation or extension of its own nation-state... It arises chiefly where and when a particular ethnicity or nation feels itself threatened in regard to its own proper character, extent or importance."[71]

A. Ethnic vs. Civic Nationalism

Most political scientists distinguish between two ways of structuring society in a nation-state: "ethnic nationalism" and "civil nationalism"[72] (see Table 3). In popular usage, civic nationalism is often called "patriotism." Miller writes,

Scholars have long detailed, and for the most part accepted, a dichotomy between civic (or political) and ethnic (or cultural) nationalisms. The first asserts the primacy of political ideals in the composition of a national identity; the second posits the ethnic group as the fundamental basis of nationhood."[73]

Ethnic nationalism defines the "nation" in ethnic terms and excludes from the "nation" anyone who is not a member of the same ethnic group. Civic nationalism defines the nation on a territorial basis. Using Ramet's terminology, civic nationalism is a based on guarantees of individual rights[74] and ethnic nationalism is based on the doctrine of "collective rights" which involve the exultation of one particular community or culture within and over a given society. She explains,

The Enlightenment era saw the preeminence of a new category of social differentiation: membership in the nation, defined in terms of citizenship�K where the state was supposed to be a citizen's state (građanska država) that protected the rights of all citizens equally�K For many postmoderns, the state is seen as ideally constituting itself as the state of a specified people �V not a citizen's state, but a national state (nacionalna država). In a nationalna država, those citizens not of the majority nationality enjoy fewer rights than other citizens.[75]

In this study, when I use the term nationalism, I have in mind "ethnic nationalism."

Table 3 �V Ethnic vs. Civic Nationalism

|

"Ethnic" Nationalism |

"Civic"

Nationalism |

|

Celebrates

inherited cultural identity |

Celebrates

the freely chosen and purely political identity of participants in modern

states |

|

Primacy

of "collective rights" (the ethnic nation) |

Primacy

of "individual rights" (the individual) |

|

Exemplified

by Nazi Germany, pre-WW II |

Exemplified

by |

|

Focus

on ethnos |

Focus

on demos |

|

"Ethnic

purity" valued |

"Multi-culturalism"

and diversity valued |

|

Special

rights given to the dominant ethnic group |

Equal

rights for all ethnic groups |

|

|

|

Another contrast scholars sometimes make is between French nationalism and German nationalism. Rogers Brubaker explains,

The contrast between

It appears that ethnic nationalism being is conceptualized differently today than in previous generations. Delanty writes,

There does appear to be widespread consensus that at some level nationalism has been closely related to the development of industrial society and the centralized state in the late-nineteenth century�K The new nationalism, on the other hand, is more the product of the crisis of the nation-state and the collapse of the modernization project... [It] is primarily a nationalism of exclusion, while the old nationalism was one of inclusion... Nationalism no longer appeals to ideology but to identity. Thus the predominant form that national identity takes today is that of cultural nationalism.[77]

Nationalism in

Rather than pointing the finger of blame [for ethnic atrocities]

at particular religious and ethnic groups who have committed such atrocities at

various times and places, we consider that the root cause of this terrible

malady has been the 'ethnic' conception and

definition of nationhood�K If

exclusive and frequently illiberal 'ethnic' nationalism has not been the

'original sin' or root of all evil' in twentieth-century eastern European

politics, it has come pretty close to that. It has poisoned the wells of

liberalism and democracy in the region for as long as independent nation-states

have existed there.[78]

I follow Bideleux and Jeffries in seeing ethnic nationalism as an inherently harmful and destructive concept. In the context of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the nationalism in question is best described as "ethno-nationalism."[79] It is based on a German, rather than French concept of nationhood. Friedman writes,

This term [ethno-nationalism] forges the concepts of ethnic group and nation, emphasizing 'the political dimensions of solidarity.' Ethno-nationalism differs from nationalism in intensity, membership, or the degree of mobilization of its adherents�K The term portrays the political repercussions of the actualization of national identity.[80]

Ethnic nationalism, in its extreme forms, is difficult to sustain,

The ferocious version of nationalism considered by many westerners as endemic in the Balkans has only ever been sustainable for brief periods by governments before it begins to soften, then fragment, then finally decay.[81]

Slobodanka Nedović, professor of sociology at

There we were in the late eighties with a new ideology and a new

task of indoctrination for all national elites�K It permeated all of life�K The

process was more or less identical in all former

B. Contemporary theories of nationalism

A recent postmodernist theory of nationalism is that of Michael Billig.[83] He calls his approach "banal nationalism." The theory considers how national identity is produced and reproduced by daily social practices." Delantry writes,

Nationalism today mo longer appeals to ideology but to identity... One of the pervasive forms the new nationalism takes is what Billig calls 'banal nationalism', the nationalism which pervades everyday life. This of course does not mean that ideology has come to an end, but that it has fragmented into a politics of identity"[84]

When Billig uses the term nationalism, he is using it to describe a practice, not a theory or doctrine and he is using the term to refer primarily to "civic nationalism." He contends that nationalism and the active reproduction of national identity is occurring continually within all nation-states. His central question is 'Why do people not forget their nationality?' and the answer he offers is that "in established nations there is a continual "flagging" / "reminding" of nationhood.[85] This "flagging" occurs in all sorts of public ways, for example, through words and symbols in songs, on flags, stamps, and banknotes, etc. Torsti writes,

Although Billig developed the concept to analyze the presence of the nation in relatively stable Western societies, the idea of banality, the taken-forgranted nature of meanings that this concept refers to and which provides a continuous background for cultural production and political discourse, is a fitting characterization of presence of history in Bosnian society.[86]

Researcher Srdjan Vucetic, who himself is Bosnian, has studied the role that humor plays a role in structuring national identity at the level of everyday life.[87] This would be another example of "banal nationalism" at the level of everyday life.

Another contemporary approach, popular around the world, is Samuel Huntington's controversial "Clash of Civilizations" thesis. This is both a post-national theory and a form of neo-primordialism. He argues that with the waning of the importance of "ideology," nation-states are losing their importance and people are returning to more basic and traditional identities,

The most important distinctions among peoples are not ideological, political or economic. They are cultural. People and nations are attempting to answer the most basic questions humans can face: Who are we?[88]

People define themselves in terms of ancestry, religion, language, history, values, customs, and institutions. They identity with cultural groups: tribes, ethnic groups, religious communities, nations and at the broadest level, civilizations. People use politics not just to advance their interest but also to define their identity. We know who we are only when we know who we are not and often only when we know whom we are against�K [89]

As the West declines, other ancient civilizations are

beginning to assert their global influence.

C. Types of nationalism

Sabrina Ramet has developed a typology of nationalism that highlights the fact that there are different types of nationalism.[91] She notes that nationalism comes into sharper focus at certain points in time in the life of a "nation," typically during crisis and always during war. She distinguishes between Croatian nationalism which she describes as defensive nationalism and Serbian nationalism, which she labels traumatic nationalism,

Defensive nationalism does not aspire to save the world or parade its glories or expand its influence or to fight and defeat a threatening world, �K it seeks rather to defend the core interests of the nation itself.

When a nation both recalls its past as rife with suffering,

catastrophe and cataclysm, and views the world as threatening, the result is traumatic nationalism... [Serbian

nationalism] draws its energy, by habit and by nature, from a reinterpretation

of

Nations and nationalism in the former Yugoslavia

Tito applied Stalin's theory of "nations" to the

Yugoslav context in post World War II

A historically formed and stable community of people which has emerged on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life and psychological make-up, the latter being manifest in a common shared culture."[93]

Nationhood, therefore, is not a racial or tribal phenomenon. While including subjective components (national character, psychological makeup, and culture) this approach is based on a relatively objective set of characteristics that must be met to establish a group as a "nation." His approach differs from the western understandings of "ethnic groups" in that it is the state, not the individual who defines group identity. In socialist societies the state "objectifies" nationality by conferring or not conferring the status of nationhood on a given community (see Table 4).

Table 4 - Stalin's "Theory of Nations"[94]

|

Socialist / Yugoslav

approach |

Western approach |

|

The

state confers the status of "nationhood" (narodi) on chosen groups.

|

"Nation" refers to the

political unit, i.e. the state.

Citizenship describes a person's relationship to the state, regardless

of his or her ethnic identity. |

|

Nationality

is different from and in addition to citizenship. It is an identity that a person can

either inherit or adopt (i.e. it can be self-ascribed). |

|

|

The

state also recognizes minority groups.

These are groups smaller than the nations with official recognition

(12 were recognized in |

The existence of a minority

group or "ethnic group" is self-determined by the group

itself. It is possible for ethnic

and minority group identities to be imagined and manipulated by individuals

and communities. |

|

|

|

Initially five social groups in the former

Bosniaks, until the late 1960s, were not

included in any of these three classifications. At that point they were recognized as a

"nation" (narod), but

unlike the other "nations" (narodi)

of

D. Terminology to be clarified

The most challenging issue I faced in the course of our research was choosing which English term to use to describe the three social groups of Bosnia-Herzegovina. While western writers usually refer to the "peoples" of Bosnia-Herzegovina as "ethnic groups" the term ethnic group has a somewhat different meaning in western societies. Table 5 helps clarify this difference.

Table 5 �V National Identity in Bosnia-Herzegovina vs. Ethnic Identity in the West

|

|

National identity in |

Ethnic identity in the

West |

|

Group boundaries |

National group are defined from outside the

group, i.e. by the state. |

Ethnic group boundaries are defined both

from inside and outside the group.

This is called the double boundary of ethnicity. |

|

Number of identities |

Each person has two primary national

identities: one ethnic (Bosniak,

Serb or Croat) and one civic (a citizen of Bosnia-Herzegovina). |

Individuals can and often do have multiple

primary identities. |

|

|

|

|

While the term ethnic group is widely used in the English speaking world, both in everyday discourse and in the scholarly literature, it is not in common use in Bosnia‑Herzegovina. Bosnia-Herzegovina is a multi-ethnic state, but Bosnians don't talk about their "ethnic group" (naša etnička grupa) or their "nation" (naša nacija). Instead they talk about their "people" (naš narod).[95]

|

Language of BiH |

English equivalent |

|

|

Narod |

People |

Peoplehood |

|

Nacija |

Nation |

Nationality |

|

Etnička

grupa |

Ethnic group |

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

Unfortunately, the closest English

translation of the term narod, i.e.

"people" is not used in the scholarly literature. Slavic researcher Teodor Shanin calls

this the "case of the missing term" in the English language.[96]

John Allcock , a specialist in South East European studies, agrees,

One of the persisting difficulties experienced by people from the English-speaking world in understanding Balkan politics is the problem of translating ideas. The term "nation" and its derivatives are potentially among the most confusing in this respect. The word which is translated as "nation" (narod) is also often translated either as "folk" or as "people's" (narodna muzika as "folk music", or Jugoslavenska Narodna Armija as "Yugoslav People's Army"). Whereas the English term "nation" tends to set in motion a chain of associations of a primarily political character, linking it to the state (especially for North Americans), for South Slavs the associations are more likely to point towards a sense of belonging to a group with a shared past and culture.[97]

Anthropologist Betty Dentich offers a similar assessment,

In South Slavic languages, the word "narod" means both "people" and "nation." Thereby, the "nation-state" is attached to a specific "nation", or "people," conceived as an ethnic population. The essential incompatibility between this concept and American definitions can be illustrated by a recurrent piece of dialogue between myself and Yugoslavs discovering that I was an American. "But what is your nationality," they would ask. "American," I would respond. "But American is not a nationality, only a citizenship. What is your descent (poreklo)? Where did your people come from?" Missing is the essential notion of American nationhood: that nationality is an attribute of citizenship, and can even be chosen, regardless of ancestry. The equation between "people" and "nation", contained within the single word "narod" provides no allowance for nationhood detached from ancestry.[98]

We have decided to use the term "nation" in our study to refer to the three narodi of Bosnia-Herzegovina.[99]

4. National Identity

Having reviewed related foundational subjects, we are now in a position to consider national identity. Jasna Milošević Đorđević, in a useful article published in the Serbian journal Psihologija (Psychology), comments that before studying national identity, two key questions that must be answered: 1) What is national identity and how does it relate to similar concepts like "nation," race, ethnic group, and nationalism? and 2) How can we classify the many and very diffuse theories of national identity?[100] We began our literature review on national identity with these questions.

A. What is national identity?

The first question that must be considered is how to define national identity. Đorđević's argues that,

It is best to begin by analyzing the meaning and structure of national identity for individuals, examining what it means in its essence, how those individuals understand and experience it.[101]

Nancy Morris offers the following definition, "An individual's sense of belonging to a collectivity that calls itself a nation."[102] Milton Esman offers a more detailed definition,

The set of meanings that individuals impute to their membership in an ethnic community [Esman's usage of this term is similar to my definition of a "nation"], including those attributes that bind them to that collectivity and that distinguish it from others in their relevant environment. A psychological construct that can evoke powerful emotional responses, ethnic identity normally conveys strong elements of continuity.[103]

National identity is only one of several forms of collective identity. "The types of identities that people choose for themselves," writes Sandra Joireman, "tend to fall into a few categories: regional, religious, racial and linguistic. "[104] In her usage of the term, national identity is the politicized form of ethnic identity that develops when an ethnic group adopts a common political identity and their ethnicity is no longer just a cultural or social identifier.[105] Her distinctions begin to break down in a context like Bosnia‑Herzegovina where the term "nation" refers primarily to a people rather than a political "state," where there is only one race and where the ethnic / religious categories overlap almost completely (i.e. Croat = Catholic, Serb = Orthodox, Bosniak = Muslim). Velikonja observes that,

The perception of national identity in eastern, central and

southern

Differences of perception exist not only between the

peoples of eastern and western

National identity developed from

medieval traditions of statehood .. [while

for Bosnian Muslims] the evolution of national identity was �V besides some

clear religious-cultural characteristics �V to a large degree a response to the

territorial appetites of their neighbors in the late nineteenth century and

especially in recent decades.[107]

The term "nationalism" is often used to describe the same phenomena as "national identity," i.e. as a descriptor of a people's sense of affiliation with their nation. This causes confusion. Đorđević admits that it is hard to distinguish between nationalism and national identity. The key question, she suggests, is "Are they essentially the same thing, differing only in intensity, or do they describe two different phenomena?"

In this study, I used the term "national identity" in a neutral way (it is neither good nor bad, it just "is") and I used the term "nationalism" in a negative way (to refer to something that is "bad"). In this I follow the approach of John Keane who passionately argues that,

Nationalism is a scavenger. It feeds upon the pre-existing sense of nationhood within a given territory, transforming that shared national identity into a bizarre parody of its former self. Nationalism is a pathological form of national identity which tends�Kto destroy its heterogeneity by squeezing the nation into the Nation. Nationalism has a fanatical core. In contrast to national identity, whose boundaries are not fixed and whose tolerance of difference and openness to other forms of life is qualitatively greater, nationalism requires its adherents to believe in the belief itself�K Nationalism has nothing of the humility of national identity.[108]

Nancy Morris' definition, "an individual's sense of belonging to a collectivity that calls itself a nation," adequately describes the individual and subjective dimension of national identity, but fails to include the objective, collective dimension of national identity that is of equal importance in the context of Bosnia-Herzegovina. As I've already indicated, I used the term national identity in this study to refer to three dimensions of identity: 1) the objective categories of national identification available in a given context, 2) an individual's subjective sense of belonging to one of those categories of identification and 3) the strong emotional sense of collective solidarity people in a "nation" feel toward others in the "nation."

Dutch professor Joep Leerssen makes the astute observation that as constructivism in social, cultural and political thought became the dominant social discourse over the past thirty years, the term national identity shifted,

From meaning an objective essence�K to something like 'collective self-awareness' �V a self-awareness which is acquired, malleable, and as such a historical variable rather than an anthropological constant; an ideological construct rather than a categorical donnée. In fact it seems to have met, and merged with, what is now its near-synonym: culture. Identity and culture have become almost interchangeable terms.[109]

In considering the emergence and development

of national identity among the "nations" of Bosnia-Herzegovina, it is

very helpful to compare Bosnia-Herzegovina with its neighbor

B. Theories

of national identity

As in the study of ethnicity and nationalism, the basic divide between theories of national identity is between primordial theories and constructivist theories. Đorđević suggests the following classification scheme (see Table 7).

Table 7 �V Đorđević's Classification of Theoretical Approaches to National Identity

|

Dimension |

Description |

|

|

Nature of |

The

primordialistic concept of |

Contemporary

approaches: instrumentalist, constructivist, functionalistic |

|

Fundamental

determinants |

Language, culture (music, traditional myths), state symbols

(territory, citizenship), self-categorization, religion, personal

characteristics and values |

|

|

|

|

|

Anthony D. Smith's suggests a different, four-fold classification of the main theories of national identity (See Table 8). I find his classification more useful.

C. Models of national identity

In our review of the literature I discovered two conceptual models of national identity and a model of national identity formation.

Table 8 �V Smith's Classification of the Theories of National Identity

|

Theory |

Description |

|

Primordialist |

Theories that are essentially primordial, i.e. that

view national identity as emerging from kinship, cultural or historical ties

that are enshrined in the collective memory of the culture. |

|

Perennialist |

|

|

Ethno-symbolic |

|

|

Modernist |

A constructivist approach that views national

identity as an elusive socially constructed and negotiated reality, something

that essentially has a different meaning for each individual. |

|

|

|

a. The "Socio-Cultural Model of Nations."

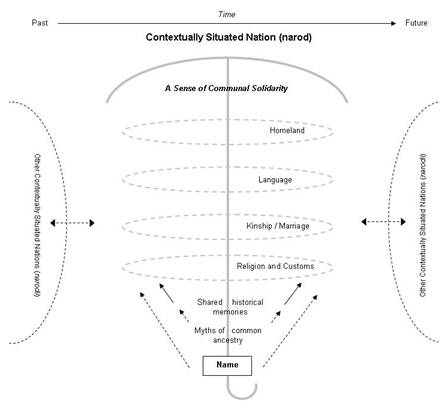

Biblical scholar Dennis During developed a Socio-Cultural Model of Nations based on the framework of the Anthony Smith��s ethosymbolism theory (see Figure 1).[111] This model postulates a concept of national identity based on the "stuff" under the cultural umbrella, but it recognizes that cultural characteristics are subject to self-definition and change by the group itself. During described his model this way,

[It] highlights key representative (not comprehensive) socio-cultural features (a homomorphic model) and is an outsider's model (etic model) that is "imposed" on the available data. It is general and abstract and therefore runs the risk of oversimplifying distinctive local ethnographic and historical information. Finally, it is in danger of being academically ethnocentric. However, models that omit detail in this way should not be seen as true or false, but rather heuristic. They invite criticism and modification--even alternative reconstruction. [112]

I found this model useful for this

study because it "fits" both the Bosnian context and is similar to

the concept of "nations" found in Scripture (see Chapter 4 of the study).

Figure 1 �VSocio-Cultural

Model of "Nations"

b. Ruhu's "Social-cultural Model of Identity."

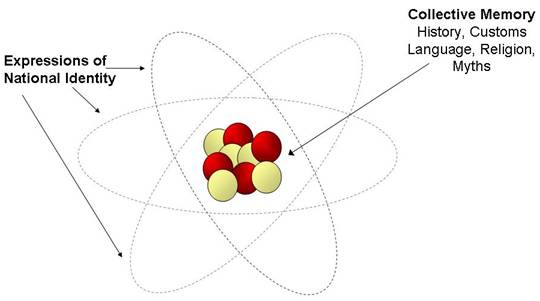

Romanian scholar Horatiu Ruhu suggests a Social-cultural Model of Identity (see Figure 2) with a slightly higher level of generality that attempts to integrate primordial and constructivist theories of national identity.[113] The model, like an atom, has two parts �V an identity nucleus core, and a continually changing expression of national identity related to the core, like protons circling the nucleus.

Figure 2 - Ruhu's Social-Cultural Model of National Identity

The nuclear core consists of

specific sociocultural values (the intangible cultural heritage of a

"nation") that have persisted over time �V items that are expressed in

"perennial" traits of national identity such as language, customs,

myths, and religion. These deep

layers of a culture (its "collective memory") can and do, however

slowly, change. Such changes have become especially apparent in the transition

from pre‑modernity to modernity and from modernity to post-modernity. Such changes are in turn reflected in

the continually changing structure of the orbiting protons.

c. Bellamy's "Development of National Identity Model."

Alex Bellamy, focusing on the development of national

identity in

In his opinion, national identity should be seen as the

result of a complex relationship between different factors that end up being

manifested at a local level and impacting individuals in multiple social

spheres.[116] In his study of

Table 9 - Bellamy's Multi-level Model of National Identity

|

Approach |

Description |

|

The "big stories" |

The first level is an abstract level of 'big stories' that distinguish

the nation from other nations. |

|

The instrumental usage of the

"big stories" by elites |

The

second level looks at the political and intellectual elites who attempt to

make sense of these 'big stories' in order to legitimize particular political

programs. |

|

"Banal Nationalism" |

The third

level examines how narratives of national identity articulated by political

and intellectual elites are constantly reinterpreted in social practice. |

|

|

|

4. Religion

Velikonja emphasizes the importance of religion for understanding national identity,

Religion is generally considered to be one of the earliest and most fundamental forms of collective distinction. The religious dimension also represents one of the most important factors in the creation of national consciousness and politics, especially in the absence of other, more compelling, factors. Indeed, the religious dimension is considered one of the most enduring factors, persisting even when other factors weaken and vanish. Churches and religious organizations, as institutionalized manifestations of religions, are social and political entities and, as such, play an important role in the creation and survival of a nation�K Religious differences play a greater role in the shaping of national identity in those states where religious heterogeneity was and is prevalent.[117]

One of the biggest challenges modern scholars of religion face is agreeing on a definition of religion. While some form of religion is universally present in the cultures of the world, the diversity of forms it takes makes definition difficult. The challenge is to come up with a definition that is specific enough to be meaningful, but inclusive enough to not leave out certain religions.

A. Religion in western societies vs. religion in collective societies

Most scholars who have studied religion in Bosnia-Herzegovina come from modern, secularized societies where religion has been marginalized. They tend to perceive religion as "a separate sphere of an individual's experience which one can choose to join, or not to join, and to change when desired."[118] Under the influence of modernity, westerners, especially Americans, have come to view one's religion as a matter of individual choice.

In the collective societies, religion is experienced differently.[119] The focus is not on the individual �V whether or not he or she is a religious person, but on the ethnic or national community as a whole. That community or "nation" already has a special "covenantal" type of relationship with their traditional religion. Every individual belonging to that community (usually by being born into it) automatically belongs to that religion. For example,

In the Balkans, entire groups of people (tribe/nation) became Christianized in mass conversions, so that one dates the conversion usually to the conversion of the king, who then, more or less by command, brings the entire people under the leadership of the clergy, many of whom stem from royal or noble households.[120]

The idea that religion is something a person "chooses" is foreign to most Bosnians. Labrine writes,

The first thing that

one must realize when examining religion in

One of the results of a collective understanding of religion is that it makes the "nation" of central importance, promoting ethnocentrism, in contrast to the western, individualistic understanding of religion that makes the individual central and promotes selfishness. Scripture judges both. Rooy writes,

Divergent views of humankind have spawned two wrong approaches with respect to people in community: an individualistic anthropology or a collectivistic sociology. Neither reflects biblical anthropology. Each person receives God��s care; each is called by his name. At the same time, no one lives to himself. The individual has existence only in relation to others. Individualism proclaims self-reliance, self-dependence, and self-development. Collectivism teaches state control, state-centered decisions, and state-directed goals.[122]

The

way religion's role in society and culture is understood varies from culture to

culture. An evangelical missionary

from American, for example, will have a very different perspective on this

than, say a nationalistic Serb in

An important invariable

quantity that must be considered when examining the religious history of

B. The narrative (or mythical) dimension of religion

Religion, according to David Filbeck, "helps to maintain society and plays an important role in forming the cognitive map through which members of society make sense of the world."[124] In shaping the way people in a society perceive reality,

Religion provides a people with beliefs about the ultimate nature of things, as deep feelings and motivations, and as fundamental values and allegiances.[125]

This is the narrative dimension of religion. The primary way religion achieves this is by serving as guardian of a people's collective narratives or myths, what some scholars call a culture's "collective memory." The popular understanding of the word myth as an imagined or fictitious story stands in sharp contrast to the way the term is used in anthropology. In anthropology, myths refer to,

Transcendent stories believed to be true, which serve as paradigms people use to understand the bigger stories in which ordinary lives are embedded. They are master narratives that bring cosmic order, coherence and sense to the�K everyday world by telling people what is real, eternal and enduring�K The language of myth is the memory of the community, of a community which holds its bonds together because it is a community of faith.[126]

Anthony D. Smith's ethno-symbolist approach locates the ��core�� of national identity in the collective historical memories of a culture (memories expressed in historical narratives (myths) and religious symbols). Today many modern scholars operate from the perspective that,

The main channel through which national identity is actively

contended and negotiated is through historical narratives�K if [as

A nation's historical memories and myths make national identity "appear clear and natural." They function as a key instrument of "cultural reproduction," that is, the passing on of national identity to the next generation,[128]

The beliefs a people holds about its shared fate represent one of the fundamental driving forces of modern society. National myths are crucial to understanding the world we live in. Yet strangely, although they are constantly being evoked, little concerted work has been done on the nature and functions of myths concerning nationhood.[129]

The role of historical myth in supporting

ethno-religious nationalism has recently become a popular field of study,

especially since the publication of the influential Myths and Nationhood in 1997.

One of the leading scholars on role of historical myth in the Balkans is

Norwegian scholar Pål Kostø. He

recently edited a collection of (emic) essays on the role of historical myth

in Balkan societies.[130] In the Introduction, Professor

Kostø argues that myths have played a key role in the Balkans in providing boundary-defining mechanisms used by

nationalist leaders to justify political legitimation of states,

We have scrutinized in particular one aspect of historical myth that has quite specific social consequences. This is the tendency to function as a boundary‑defining mechanism that distinguishes various communities from each other. The factors that lead members of two groups to see each other as different rather than as members of the same collective are often 'mythical' rather than 'factual.'[131]

Kostø identified four basic categories of

myths that serve this function:

Myths of sui generis, of antemurale, of martyrium, and of antiquitas.

Velikonja notes that a nation's "mythology" is both internally cohesive, i.e. part of a larger whole, and dynamic, i.e. continually changing. A society's "mythology" serves three (religious) functions: integrative, cognitive and communicative. Historical and religious myths "integrate" a society by explaining who is included and who is excluded (what Kostø calls "boundary-defining mechanisms"). They serve a cognitive function by "explaining important past and present events and foretelling future ones" and a communicative function by providing "specific mythic rhetoric and syntagma." [132]

He suggests a nation's myths fall into two broad categories: traditional and ideological. Traditional myths are those stories familiar to all or most members of a society �V stories of key events and people from the past. Ideological myths, in contrast, while drawing on "ancient wounds" from the past, look to the future and suggest a specific course of action. These ideological myths are usually articulated by a small group of people, usually academic or religious leaders, and used by political leaders to "inspire collective loyalties, affinities, passions and actions" to "mobilize and energize political behavior."[133]

C. The social (or political) dimension of religion[134]

Sociologists generally argue that society shares five major social institutions: government, religion, education, economics, and family.[135] Religion, in all societies, has a social or political dimension. In an individualistic, secular society, religion is separated from politics and becomes a matter of personal preference. In a collective society, religion and politics work together to strengthen and protect the ethnic community from outside threats. In this approach,

Religion [is]�K enmeshed with all other cultural and civilization aspects of life to the degree that it [is] �K not possible to clearly delineate where religions ended and politics, art and science began, and visa versa. Among the great world religions, Islam to this day most closely maintains this model. Muslims frequently will say that Islam is not a religion but a way of life.[136]

This is the way religion is understood and experienced in Bosnia-Herzegovina. An almost complete overlap exists between the three main religious communities and the three ethnic communities. Bosnians, when referring to themselves or their neighbors, use the ethnic labels (Bosniak, Croat, and Serb) and the religious labels interchangeably (Muslim, Catholic, and Orthodox). Religion and ethnic identity have become "so enmeshed that they cannot be separated."[137]

In societies where religious and ethnic identity and nationalism are congruent and where a religious institution exists that is seen as the 'progenitor and guardian of the nation' the tendency exist for an authoritarian religious monopoly to develop. Usually this monopoly portrays itself as "natural" political order. The phenomenon is strengthened by the strong tendency toward authoritarianism in the Balkans.

D. Historical and social factors.

This intermingling of religion and ethnic identity in Bosnia-Herzegovina took place over many hundreds of years in a specific historical and social context. During the period of Ottoman rule in Bosnia-Herzegovina, religion, not nationality, was the very essence of the identity of Bosnians. Religious institutions and religious leaders played a leading social and political role in Bosnia-Herzegovina. With the rise of national ideologies in the nineteenth century, an attempt was made to substitute religion and religious identity with national and political ideologies. This resulted in the development of an interdependent relationship between religious leaders and nationalist politicians. Religion became "so closely intertwined with cultural and national programs and national ideologies [that it] remains at the heart of a people's collective understanding."[138] For this reason, an examination of national identity in Bosnia-Herzegovina must include an examination of each "nation's" religious history. "Although the Communists tried to loosen or even dissolve this century long symbiosis, it is obvious that they failed to do so."[139]

E. Religion, politics and nationalism.

In such a context, instead of the ideal being the separation of church and state, the ideal is that of a symbiotic relationship between religious leaders and political leaders �V each depending on the other for support, and each working for the good of the nation. From the mid 1980's on, as Yugoslav began to fall apart and nationalism re-emerged, religion became increasingly important and the influence of religious leaders increased proportionately. This symbiotic relationship between ethnic nationalism and religion does not make sense if religion is seen in a modern, individualistic sense. Mojzes refers of this as ethnoreligiosity. Vrcan calls this "the politicization of religion" and the "religionization of politics." [140] Vjekoslav Perica coined the term "ethnoclericism" to describe the same phenomenon,[141]

Ethnic churches are designed as instruments for the survival of ethnic communities�K They are authoritarian-minded and centralized organizations capable of organizing resistance against an outside threat and maintaining stability inside the community. The upper section of clerical hierarchies exercise a hegemony in ecclesiastical affairs (at the expense of lower clergy and lay members). Ethnoclericism is thus both an ecclesiastical concept and political ideology. It champions a strong homogeneous church in a strong homogeneous state, with both institutions working together as guardians of the ethnic community. Ethnic churches depend on the nation-state as much as the nation depends on them.[142]

The primary role of institutional religious leaders is not thought to be that of "nurturing the faith of believers" but that of "protecting and preserving the ethnic community from outside threats." The ultimate sin is not disobeying God's moral laws, but defection, i.e. conversion to another faith.

Cultural anthropologists explain that religion can be conceptualized as a systems of beliefs, symbols, behaviors and practices."[143] Symbols serve to integrate and give expression to inward beliefs,

In simple terms, myth is the narrative, the set of ideas, whereas ritual is the acting out, the articulation of myth; symbols are the building blocks of myth, and the acceptance or veneration of symbols is a significant aspect of ritual�K Myths are encoded in rituals, liturgies and symbols, and reference to a symbol can be quite sufficient to recall the myth for members of the community.[144]

The use of religious symbols became important in Bosnia-Herzegovina with the rise of ethno-religious nationalism. Religion provided,

Nationalists with a rich source of symbols and rituals with which to inspire national identification, separateness, and internal cohesion of the ethnic group.[145]

Religion and the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina

In

the recent war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, religion was clearly a factor. Dunn is certainly correct to assert that

"the character of the conflicts raging in the former

�P The war was a religious war

�P The war was not a religious war but religious leaders and religious symbols were manipulated by ultranationalists to achieve their purposes

�P The war was an ethnoreligious war.[147]

Religious

nationalists led the way in portraying the war as a religious war. For example,

a history textbook in use among Serbs blamed the war on the

Launched a battle against Orthodoxy and Serbs through the Catholic Church and its allies.[148]

Those

who hold this perspective contend that specifically religious divisions give

the conflict a dimension similar to the other religious wars

One of the problems with this approach is the largely secular perspective of people in the region. Many people identify themselves as Muslim, Orthodox or Catholic but do not profess or practice any religion. Most of the recent political and military leaders are secular people, not people motivated by religion. At this point, religious identity begins to lose its religious meaning. Mojzes concludes, "insofar as this is a 'religious' war, it is being fought largely by irreligious people who wear religion as a distinguishing badge but do not know what the badge stands for."[151]

Another problem with this position is that in Bosnia-Herzegovina, not all religious leaders have supported the ultranationalist's vision of culturally-homogeneous societies. Many leaders, especially in the Muslim and Catholic communities, have insisted that their future depends on the success of a multi-cultural, multi-religious, multi-ethnic state in Bosnia-Herzegovina. An excessive focus on religious and cultural differences tends to obscure other factors �V political, economic and military. Peter Kuzmić argues, "the genesis of the war was ideological and territorial, not ethnic and religious."[152] Powers argues that the roots of the war are better understood by looking at the rise of extreme nationalisms, incited by former communists who sought a new ground of legitimacy. He writes,

The war's barbarity and intractability have been due less to ancient hatreds than to the fears intentionally induced by warlords and criminals, the logic of extreme nationalism, which thrive by inciting religious and cultural conflict and the hatred and vengeance that feed on and intensify cycles of violence.[153]

It

is clear that religious leaders did contribute to ethnic separation and

national chauvinism by encouraging ethnically-based politics, by sanctioning

and sanctifying wars of national self-determination, and by showing little

concern for the human rights and fears of other ethnic and religious groups.[154]

They were more than neutral religious leaders who were manipulated by

nationalistic politicians. Paul

Mojzes caustically observes,

To put it bluntly, the leaders of each religious community justify their enthusiastic and uncritical support of rising nationalism among their peoples. yet they condemn rival religious leaders for an "unholy" support of nationalism, which, they believe, contributed to the outbreak of the war.[155]

Mojzes and others support a third position - that the war had an ethnoreligious character. In this perspective, the conflict was about nationalism, not religion per se. While the war was primarily "ethno-national" not religious, it did have a religious dimension because leaders of each religious community provided "enthusiastic and uncritical support of rising nationalism among their peoples."[156] An example of this would be a Croatian writer's portrayal of the war as,

A real war for the

'honoured cross and golden liberty,' for the return of Christ and liberty to

Both Partos and Goodwin agree with Mojzes,

Religion is so intrinsically bound up with nationalism in the region that its role cannot be ignored. Even if it is exploited by people with no religious beliefs, is misused for propaganda purposes, or is applied as a thin veneer to conceal other ulterior purposes, religion has been a component of the conflict that in recent years has torn countries, nations, and communities apart.[158]

Many

religious leaders were willing participants in nationalist causes and not

merely co-opted by powerful political elites.

5. Missiology and the issue of ethnicity and national identity