Youth-Centric

Movements:

Trends and Challenges for

The Modern Missions Movement in India

Joseph Frederick Kolapudi

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org. October 2018

Abstract

Over recent generations, a paradigm shift occurring within the modern missions movement has had a profound effect on the way missionaries and workers in cross-cultural settings are engaging in missions. This shift relates to local ethnic peoples designating national missionaries to reach their own countries for the sake of the Gospel. Increasingly, the missionaries being sent out are young, highly-educated professionals, especially within the Global South. This article explores how youth-centric movements are sparking changes within today’s missions movement, as well as how India, known as the world’s largest democracy, has a significant role to play in Christian missions.

Introduction

From the first wave of the Protestant modern missions movement that reached the shores of South India, pioneers such as William Carey initiated a new way to both view and engage in cross-cultural missions, paving the way for scores of other missionaries to follow. This movement can still be felt and seen today, with far reaching effects on the Global South and beyond. In particular, the second and third waves of current missionaries today are now increasingly being sent from their home countries to the West.

According to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, research shows that by the year 2020 India will be amongst the top ten countries in the world in terms of growth rate of Christians, with a rate of almost five percent (Johnson 2013, 15). Such research suggests how the modern missions movement has taken hold in formerly receiving missionaries that are now becoming sending nations.

However, questions remain about who the national missionaries are and how they are being trained at the local level to reach their own nations, and the nations of other continents, for the sake of the Gospel. In relation to the biblical engagement within local populations, we turn to the world’s largest democracy, known as the nation of India. As a nation coming out of British colonialism to become an independent nation state in 1950, India has seen Christianity continue as a religion that has remained a minority in terms of cultural acceptance.

Initial Youth-Centric Research Findings

In order to explore further the cause and trends related to biblical engagement within the Indian culture, a recent study was undertaken in joint collaboration between the Forum of Bible Agencies International (FOBA) and its Indian counterpart, the Indian Forum of Bible Agencies (FOBAI) (Srinivasagam, 2015). This study points to a number of findings, in particular, the biblical engagement of “Next-Gen,” referring to youth of 16-30 years of age.

This particular demographic was chosen due to several reasons, the most poignant being that, amongst the current population of India’s 1.3 billion inhabitants, approximately 65% are 35 years of age and under, according to research conducted in the India Leadership Study (David 2002). Other reasons include current growth trends of India’s population, higher education demographics, and the predicted increase of youth over the next several decades. For the purposes of research, an alliance of more than 25 leading international Bible agencies, mission organizations, and local churches began to explore these trends with a focus on engagement amongst the Next-Gen youth, gathering and collecting data from over 1500 respondents, primarily from India, and also including respondents from Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh, Chin, Pakistan, Myanmar, and Bhutan (Srinivasagam 2015, 12).

At the outset, the research methodology proposed to tackle such a seemingly large populace in three major areas: (1) missiology audience research, (2) technological media research, and (3) program innovation (Srinivasagam 2015, 7). The intention behind the research survey was to investigate the link between Scriptural engagement and the current methods utilized by youth designated by the Next-Gen demographic. This research initiative was then entitled, Exploration of Scripture Engagement amongst Next Generation in South Asia (Srinivasagam 2015), which was gathered in two phases of preliminary findings and comprehensive findings.

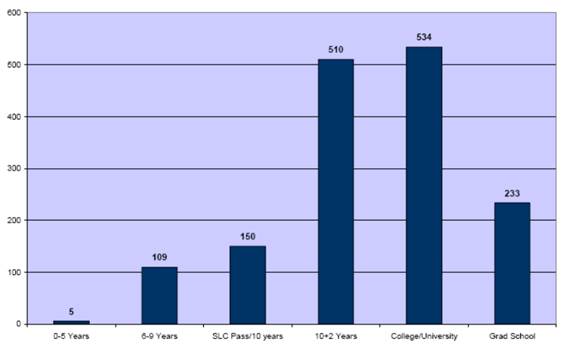

Regarding the respondents, research findings showed that approximately 498 respondents were 16-20 years of age; 661 were 21-25 years of age; and, 382 respondents were 26-30 years of age (Srinivasagam 2015, 14). The indicator of biblical engagement among these particular demographics was referred to as Frequency of Exposure (FOE). From the respondents as mentioned, those of ages 16-20, as well as of ages 21-25, had the lowest FOE rates among all respondents surveyed (Srinivasagam 2015, 14). As shown in Figure 1, the majority of respondents had a higher education from college or university.

Gender also has an impact on the FOE rates in relation to biblical engagement. Of the total respondents, 774 were male and 767 were female, with the latter having a higher FOE rate (Srinivasagam 2015, 18). Additionally, of the total respondents, 129 respondents had at least one parent being a Christian, while 94 had neither of their parents as Christians (Srinivasagam 2015, 20). These findings point to the fact that women usually have a stronger inclination to engage with Scripture, whereas male counterparts often scored lower on access and Biblical engagement, due mainly to reasons described below.

Figure 1: Respondents by Educational Levels

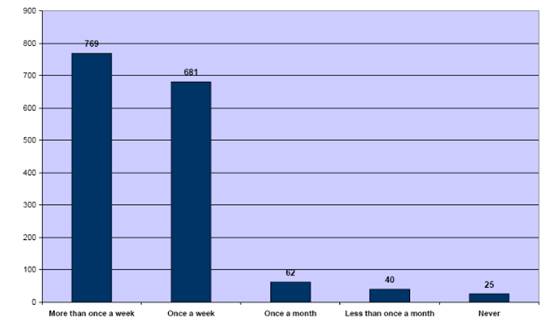

The majority of respondents attended a local church gathering more than once a week, showing that those who did so had higher FOE rates in comparison to their counterparts who attended church just once a week (see Figure 2 below). Results show that there is a linkage between church attendance leading to higher FOE rates, if the attendance exceeds the regular rate. Of the survey respondents, those who were not able to attend a local church gathering cited several reasons, including personal difficulties and lack of Scriptural understanding (Srinivasagam 2015, 26). Many (39%) cited lack of time, while 29% indicated that distance travelled was a key hindrance in lower church attendance, resulting in lower FOE rates.

However, combating these hindrances required alternative methods of engagement, especially amongst Next-Gen youth exposed to cultural trends and new technologies. The research conducted also took into consideration the utilization of social media and Bible software across all age groups as indicated. The use of social media and Bible software had a positive bearing on FOE rates across the board, the most frequently used social media platform being Facebook and Google Plus, along with Bible Gateway and YouTube.

These key findings seem to suggest that higher educational rates have a positive bearing on FOE, coupled with the engagement on a local level with a local church gathering. However, the major demographic with the lowest impact average across all regions included in the survey research was the 16-20 age bracket. Primary reasons for the low FOE rates among this particular demographic are outlined below, especially regarding Scriptural engagement on both a reading and listening level.

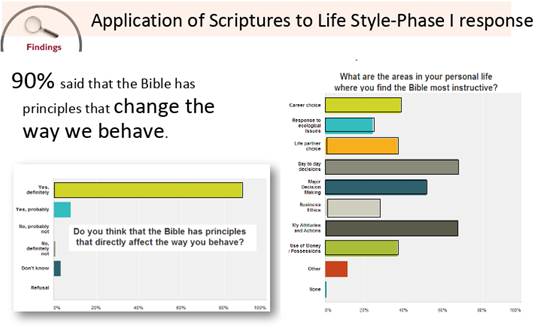

In terms of FOE engagement rates, most of the respondents indicated that they believe the Bible has principles that change the way they behave, with the major influences being the impact on day-to-day decisions, attitudes and actions, and career choices (see Figure 3). However, in comparison to the issues that the youngest Next-Gen demographic faces, the top three issues outlined by respondents had little to no relation to those of their previous respondents. In actuality, the issues facing this demographic were much more serious.

Figure 2: Frequency of Church Attendance

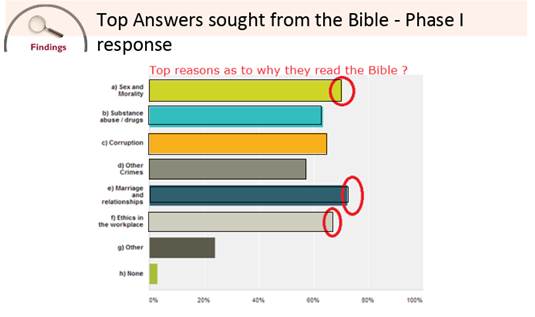

The data collected point to deeper relational issues that impact decisions made by the Next-Gen demographic in relation to both peers as well as to wider society. In regard to these issues, the major areas described were more related to issues of morality, including decisions regarding sex, marriage, and relationships, as well as ethics in the workplace (see Figure 4). Unlike the actionable results relating to day-to-day decisions, attitudes or career choices, the most poignant decisions made by this age bracket were in relation to the impact on long-term behavior. As aforementioned, this distinctive set of concerns has a major impact on the FOE of youth in comparison to that of their counterparts.

As much as the Next-Gen age demographic are facing such issues, one noteworthy point is that higher education correlates positively with higher FOE rates involving biblical engagement and church involvement, regardless of relational and morality issues of consequence. The main reason for such a correlation is that, unlike other age demographics, this particular youth age group has sparked a movement in response to the social and cultural issues as aforementioned, and this youth-centric movement, in so doing, has changed the way the modern missions movement is impacting the Global South.

Figure 3: Response to Biblical Impact

The paradigm shift has caused a major ripple effect throughout the country on a national scale, in that the Christian community, and the wider society, has been conversely impacted by the positive response of the youth-centric movement in response to issues of morality and relational dilemmas. As can be seen in the discussion below, the spark of the youth-centric movement in the modern missions paradigm has been cause for change on a far-reaching scale.

Figure 4: Response to Relational Issues

As the research points to a significant push by youth in response to various stimuli related to engagement with Scripture, the results have uncovered several unanswered questions, mainly in relation to the response of the local church. Unlike the first wave of the missions movement, the second and third wave of missionaries have primarily been made up on national missionaries trained by cross-cultural trainers, who now have enabled the local church to train their own members. However, the modern missions movement has paved the way for youth to lead a movement specifically engaging their own demographic. This youth-to-youth movement has the potential to equip emerging leaders in all areas of society, in order to have a wider impact for the sake of the Gospel.

Due to the widespread number of Next-Gen youth, as the research shows, a unique opportunity has come to the forefront of the modern missions movement. This opportunity pertains to the response to social and relational issues that stem from a much deeper, spiritual search. Unlike the previous generation, Next-Gen youth have the tools necessary to implement change at a far-reaching level, and in a relatively short period of time. As aforementioned, the use of digital tools, such as Bible software and social media, has led to a niche opportunity for the youth of large nations, such as India, to be involved in a youth-centric movement.

Such a model of missions calls for strategic direction, trainings and resources, in order for the youth of India and other nations within South Asia, and the Global South at large, to be thoroughly equipped for the effective communication of, and engagement with, the gospel. Certain mission agencies and organizations have begun the work of equipping, encouraging, and engaging youth, including well-established initiatives such as Interserve, IMB, CMS, YWAM, TEAM, Pioneers, and others. However, new organizations led by Next-Gen youth, especially within India, have begun to initiate youth-centric movements with the support of established organizations. These movements been effective, due to the focus on primary issues affecting youth, tailored solutions to these issues, and the provision of strategic initiatives and solutions to meet the need of the hour. Unlike previous movements, this youth-centric movement is led by the youth, and for youth.

Research Implications

Through Indian-based initiatives, such as Destiny, a Christian platform for Next-Gen youth, there have been organizations developing and targeting large sectors of professional industries, such as the growing Information Technology (IT) industry within North India. Pioneered by a Next-Gen young leader in North India, one initiative in which a safe space for young, Indian IT professionals is provided outside of the professional sphere has gathered significant numbers of youth to what has become known as the THI (Third Home Initiative). This model has been successful in drawing numbers of believers and non-believers into a provisional place where the gospel is shared and lives have been transformed. Many of those involved in the initiative have dealt with social and relational issues, but as a result of the initiative have been able to identify answers to these issues.

As much as such initiatives have taken their time to establish a firm footprint within Indian society, local ethnic platforms have started to form to raise the banner for other youth-centric movements to follow. In South India, a region of the nation which has had a long-standing Christian tradition, the corporate business world has taken over large metropolis locations. Corporate fellowship networks held within the city have had a major impact in bringing together young corporate workers; one such network is known as Interface. In addition to holding monthly meetings and outreaches, this particular corporate Christian network also brings together large gatherings outside of the corporate offices and within the greater Hyderabad region, in order to facilitate the spread of the gospel message.

Emerging church plants have also been planted by young professionals who are bi-vocational leaders, with close proximity to business and IT hubs, in order to bring together larger groups of Next-Gen youth to the church gatherings. Meeting in rented office spaces, public halls, and schools, these church plants have grown exponentially, not only in size, but also in meeting the needs of young, highly educated professionals.

However, the larger need that remains to be filled is the gap in Scriptural engagement and collaboration between youth and the local church. As much as mission agencies and organizations have made significant progress in sparking a number of youth-centric movements, unfortunately these have been few and far between. There still exists a gap between church initiatives and biblical engagement tailored towards the Next-Gen youth. Much of the reason for this gap can be found in the cultural paradigm of the ingrained caste system.

Unlike their Western counterparts, local churches in India still suffer from the effects of the caste system, which ostracizes and separates social classes through a cultural and spiritual divide. Even though many second- and third-generation believers have forsaken the caste sentiment, the local church still remains significantly affected by the entire caste system. Due to this effect, even though youth-centric movements have gained traction within the corporate world and wider society, the church has remained unengaged with the youth, who have disengaged as a result.

Furthermore, the traditional church established within India falls under the Church of North India (CNI) and the Church of South India (CSI). Functioning within the tradition of Anglicanism, both the CNI and CSI churches still dominate the rural landscape as well as the inner city. However, Next-Gen youth, who often leave the villages for the metropolitan areas due to opportunities for employment or higher education, either shift to churches attended by young professionals or do not attend church altogether. In this way, a gap still exists between the youth and the church today.

Recognition by the church of the large populace of youth within the rural and metropolitan areas should call for youth-centric movements to lead and equip emerging youth for the purposes of biblical and gospel outreach and engagement. For the majority of youth, the lack of awareness and opportunities for engagement has led to a gradual decline in church attendance, less involvement in Christian fellowships, and avoidance of church-based initiatives.

Even so, partnerships between the local church and youth-centric movements do in fact exist. Youth-led meetings, retreats, and outreaches within villages and cities have proven to work well in recent years. The major shift for churches has been to relinquish control of programme-based initiatives and turn over leadership roles to the younger demographic; such control continues to involve a power struggle for many of the established churches. However, changes brought about by the youth-centric movements, and their impact on the younger demographic and society at large, are beginning to be recognized by the church.

The India Missions Association (IMA), a nationwide network that is the second-largest mission network in the world with over 250 mission agencies and churches, in 2004 inaugurated a national youth leaders conference, bringing together youth leaders from all over the nation. As a result, the CSI, CNI, and other traditional and long-established churches have been committed to identifying young leaders within their own congregations to represent their churches at this nation-wide annual gathering. Over the years, the gap between the missions agencies and the local church has begun to close, with the cross-collaboration of youth across the country converging in an effort to be part of a nation-wide movement of change.

As the modern missions movement has shifted its paradigm in order for the youth-centric movement to make its mark, a new conceptualization of traditional methods has taken place, and it continues to evolve. One of the most significant reconceptualizations has been the adoption of the business-as-mission (BAM) model. Bringing together both the business platform and the mission-minded outlook of witness within the country, this particular model has been extremely successful in adoption to the Indian marketplace.

Several local Christian business leaders have been able to pioneer new businesses to serve the wider community, and in so doing have both become major contributors to society and opened up new opportunities to engage with the Christian church and the non-believers within the corporate world. Utilizing this two-pronged approach, a large number of young professionals across several industries have responded well to the witness within the workplace approach and have benefited greatly, and, as a result of their witness, have begun to witness to others.

For the Next-Gen youth, this approach to participating in youth-centric movements has widened the net in regard to the missiological paradigm. As a result, there now exists a platform through which work and witness can co-exist within a Christian environment.

Additionally, the repercussions within the Indian diaspora at large as a result of youth-centric movements have been widespread. Beyond the borders of the South Asian nation states, the overseas diaspora has also become a contributor to, not only a beneficiary of, youth-centric movements. Many business-as-mission initiatives, also known as Great Commission companies, have bases both in India and in overseas locations. As a result, the wider diaspora has felt the effects of the youth-centric movement, and the young professionals within India have had the opportunity to work cross-culturally from within their own Next-Gen demographic. The change within the Next-Gen youth leaders and individuals has also led to positive changes within workplace culture, faith-based outreach and engagement, and wider witness across multiple locations. For the Indian diaspora, this platform has enabled many of the previously isolated youth to become reconnected and re-engaged within the Next-Gen age group.

Within the widespread diaspora community, the changes to the mission dynamic have not come without complications. Due to the plethora of organizations being founded and run by Non-Resident Indians (NRI’s), naturalized overseas citizens, and second and third-generation Indian Next-Gen leaders, much of the focus has been centered on competition, and collaboration has been sparse. Outside of India, the case is reversed, due in part to South Asian diaspora communities still remaining a minority, even within the multicultural framework of open nation-states. However, within India itself, the majority of youth find it difficult to connect or collaborate within their own demographic, due to societal pressure to perform, family and parental obligations, and, of course, the ingrained caste system.

Despite the emphasis on Christian heritage and upbringing, as the previous research findings show, the primary research undertaken has limited the labelling of impending outside influences that have a bearing on Biblical engagement amongst youth, and their implications in limiting this said engagement. One of the primary factors can be attributed to the caste system. Though technically the caste system does not apply to those from a Christian background (as the caste system divides social classes within the framework of Hinduism), new converts, especially first- or second-generation Christians, often trace back their caste to their parents or ancestors in an effort to secure social standing, employment, or even for future settlements, including marriage. As a result, many of the newer church plants and communities still harbor this “secret” caste sentiment when establishing their church initiatives and outreach, especially as it pertains to the Next-Gen youth.

However, the reality of today’s missions movement has begun to shift the balance of power from the clutches of tradition to the openness of opportunity in the hands of the Next-Gen youth as part of the youth-centric movement’s forward progress. Though the progress has been slowed by such indicators as shifting political influences, migration issues, and the everyday problems affecting youth worldwide, the youth of India seem surprisingly optimistic that their reality will not be defined in the same way as with their predecessors. As a result, the changing dynamic of participation within the modern missions movement, and inclusion of Next-Gen youth has caused the youth-centric movements to catalyze new leaders who are shaping the way that India, and the world, is viewing missions across the globe.

Conclusion

In summary, the

shift within the modern missions movement from the hands of seasoned

practitioners and senior church leaders to the emerging leaders within the

Next-Gen youth demographic has seen widespread change within countries such as

India. However, there remain major issues in relation to biblical engagement,

societal pressures, and cultural complications that remain problematic to youth

within this age range, as the research shows. Nevertheless, within the

youth-centric movements, new leaders are catalyzing change across

denominational, geographical, and ethnic borders to inspire change among youth

to lead by example, collaborate across cross-cultural locations, and spur one

another to the forefront of missions engagement. As a result, the larger South

Asian diaspora has seen and felt the far-reaching effects of change and have

become changemakers within their own communities. For the emerging generation,

this new standard of global engagement for the modern missions movement is one

that sees the youth-centric movement as a forward-moving trend for the

foreseeable future.

References

Johnson, T. (2013). Christianity in its Global Context – 1970-2020. Society, Religion, and Mission, p. 1-92.

David, D. R. (2002). India Leadership Study – A Summary for Indian Christian Leaders. Retrieved from http://www.firstfruit.org/india-leadership-study/. Accessed August 23, 2018.

Srinivasagam, T. (2015). Scripture Engagement and NextGen in South Asia. Indian Forum of Bible Agencies. Retrieved from http://www.forum-intl.org/. Accessed August 24, 2018.