Orthoproxy:

Ethical Storytelling in Cross-cultural Engagement

M. Andrew Gale

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, April 2020

Abstract

Emerging generations are growing up in a world surrounded by political correctness, where how one speaks about a person, situation, or issue matters. This is especially true for millennials raised in the United States. Missions has utilized story throughout its history as a way to encourage both financial and physical support of global work. But how one tells the story matters – and it matters even more to millennials. Using Carmen Nanko-Fernández's concept of orthoproxy (speaking rightly on behalf of another), I explore the challenges and opportunities of storytelling and how one might engage in ethical storytelling that is captivating to the reader, while maintaining the dignity of all involved.

Key Words: ethical storytelling, orthroproxy, millennials, mutuality

Introduction

Global ministry propels people into cross-cultural situations. These settings are certainly found outside one's own country but also domestically in cities, or even in smaller communities and even villages. In almost all cross-cultural settings, missionaries must connect those who have sent them out to their ministries, whether for financial support or physical assistance through short-term teams. Because of the need to bridge the cultural gap between home-base supporters and missionaries' contexts of ministry, there is a need to tell the story of the work God is doing. But how do missionaries describe, for instance, a financially impoverished community in rural Bangladesh to a supporting church in suburban Indianapolis, USA? Or how does someone explain the experience gained on a short-term trip with family and friends in a way that helps them truly understand the foreign culture visited? Without a frame of reference, the storyteller must give descriptive details, elements that pique the senses, and curious realities that differ from daily life in their home culture. But how do missionaries do that without caricaturing the people and context in which they work?

For years, missionaries, missions agencies, and local churches have told stories about the work God is doing around the world. They told stories in ways that captivated imaginations and challenged others to follow in their path. As millennials begin engaging in global work, how will their experiences be shared with those in their home countries? This article first looks at two traits of millennials which influence their storytelling. Second, the article considers the concept of orthoproxy proposed by Carmen Nanko-Fernández and explores how that construct might help missionaries, missions agencies, and local churches process ethical storytelling. Finally, the article offers a usable framework, closing with three principles of orthoproxy that can aid in telling stories in ethical ways.

Two Millennial Traits

Millennials, the age group often understood as those born between 1980 and 2000,[1] are one of the most researched age demographics. Researchers of millennials offer a large variety of evaluations, from bemoaning millennials' work ethic to praising their entrepreneurial spirit. What we know about millennials is that they are the largest and considered the most diverse generation in U.S.-American history (Clark 2007:28; Howe and Strauss 2000:4; Rainer and Rainer 2011:96). Though there are many identifiable generational characteristics of millennials, two highlighted here connect with ethical storytelling and global ministry: millennials value global engagement, and they value language.

First, millennials value global engagement, and they are poised to be one of the most globally aware generations – primarily because of access to technology and opportunities for travel (Gale 2018:78-88). In terms of technology, millennials do not just consume technology, but it seems to be woven into their intrinsic fabric of existence. For instance, roughly one-third of millennials' waking lives are spent on a computer (Rainer and Rainer 2011:198). Also, 83% of millennials say they sleep with their cell phones (Raymo and Raymo 2014:15).

Technology is not just entertainment but is increasingly becoming used by millennials as a force for social change. Millennials see technology as a means to remedy social problems (Clark 2007:28). The president and founder of the "Millennial Impact Report," Derrick Feldmann, wrote of millennials: "The first generation to grow up with digital outlets for their voices is turning them into megaphones for good" (Feldman 2017). Millennials want to use technology to express their experience and change the world. And, because of technology, they know they can engage in global change without leaving their homes (Kling 2010:47).

For many millennials, though, technology is just a starting point. With the increased ease and affordability of global travel, millennials can actually engage in person with global issues they learn about through technology. In a study limited to the U.S., Robert Wuthnow and Stephen Offutt estimate 1.6 million churchgoers participate in short-term missions trips annually. This number includes more than just millennials, but the research notes an increase in international travel to 12% for those who were teenagers in the 1990s (as opposed to only 2% for those who were teenagers in the 1950s, 1960s, or 1970s) (Wuthnow and Offutt 2008:218). As millennials travel and engage cross-culturally, they encounter people who are affected, whether directly or indirectly, by injustice in ways they have not noticed before. As the authors of Advocating for Justice express, through international and domestic missions trips millennials also encounter poverty in ways they have not experienced themselves and in turn become justice and poverty advocates (Offutt et al 2016:122).

For some this extensive access, through technology and travel, leads to apathy, a sense that the troubles in the world are overwhelming and unsalvageable. But for others it brings to light issues propelling them toward action. Brian Steensland and Philip Goff pick up on this characteristic, and in response they are studying the changes happening within the evangelical Christian community as evangelical millennials are living in newly accessible cultural contexts. They suggest that "consciousness-raising movements," begun to share about specific global injustices through technology, have led to a wider awareness of global injustices world including inequalities, sex trafficking, and health-related illnesses (Steensland and Goff 2013:16).

Second, millennials value language, especially as it relates to how one speaks about another person. This value is neither millennials' invention nor their innate trait, but it emerged from years of socialization (especially in school) that required political correctness. Millennials use politically correct speech almost without thinking, and it has become such a part of their culture that they are keenly aware when other generations do not adopt the same appropriateness in speech. As one observer of the prominence of political correctness in the millennial generation writes, "where Boomers once sought to promote progressive values, Millennials want to minimize hurt feelings. Where Gen Xers once touted resilience and grit, Millennials tout tolerance and inclusiveness" (Howe 2015).

Why are millennials this way? Neil Howe and William Strauss, considered two of the most prolific writers on the millennial generation, suggest that "at any given age, every rising generation defines itself against a backdrop of contemporary trends and events" (Howe and Strauss 2000:46). In addition to socialization through education, a number of events have shaped this generation and influenced their political correctness including 9/11, women's marches, and movements like Black Lives Matter. It is important to understand, as Neil Howe points out, that millennials' use and acceptance of politically correct language is not necessarily part of a partisan or political stance as much as it is a socially conditioned part of their lives (Howe 2015).

In sum, millennials are globally engaged through technology and travel, and they are passionate about making a difference in the world. They also care about how people speak about others. As missions agencies and churches look to connect with millennials, for both missionary service and financial support, they must learn to share stories that are both captivating and ethically grounded.

Orthoproxy

Missions already has a history of telling captivating stories. From the early days of global engagement, missionaries have shared stories of their experiences. Books about missions work have been around for generations: writings by missionaries like Hudson Taylor and William Carey have called Christians to engage in global missions. There are also more recent iterations, like books written by or about the life of Jim Elliot, Brother Andrew, and Richard Wurmbrand. These stories were not just meant as photographs into the life and ministry of a missionary: they were meant to inspire others to take up the mantle and join the work. But when authors want to inspire, it is easy to lean on storytelling techniques that do not express the full story. Emmanuel Katongole and Chris Rice note, "The worst evils are committed not only in the name of evil but also in crusades in the name of fixing what is broken" (Katongole and Rice 2008:24). The problem is often not the intention in storytelling, but how that intention gets expressed.

A number of years ago, I ran across Carmen Nanko-Fernández's book Theologizing en Espanglish: Context, Community, and Ministry. The title immediately caught my attention. Nanko-Fernández is a Latin@ theologian who is professor of Hispanic Theology and Ministry, and director of the Hispanic Theology and Ministry program, at the Catholic Theological Union, Chicago, Illinois. Her book, published in 2010, looks at a number of theological concepts emerging from hybrid identity, such as the hybridity of Christ and issues related to immigration.

There was one concept that especially caught my attention and has stuck with me, Nanko-Fernández's concept of orthoproxy. Nanko-Fernández situates her term orthoproxy in relationship to the terms orthodoxy and orthopraxy. Orthodoxy, or right beliefs, and orthopraxy, or right actions, are part of an ongoing conversation, especially among Latin@ theologians, about which is primary, or which is the foundation for the other. Liberation theologians challenged the primacy of orthodoxy, leaning on orthopraxy as the way in which we learn and refine orthodoxy.

Within this duet of terms, Nanko-Fernández has offered a third concept, orthoproxy, or the right way of speaking on behalf of or representing another. The concept came out of Nanko-Fernández's own experience. As a Latin@ theologian, she said she was often asked to speak about the challenges of being an immigrant. She felt ill-equipped to respond to these questions since she was not an immigrant, having grown up in the Bronx in New York City. Though Nanko-Fernández has experienced discrimination because of her ethnicity, she was careful to point out that it was not because she was an immigrant. Speaking about the immigrant experience was thus outside the realm in which Nanko-Fernández felt comfortable. At the same time, there was tension, as Nanko-Fernández recognized, because it was important to share about the immigrant's plight and to educate those interested in the challenges that immigrants in the U.S. and elsewhere face. Her struggle was whether it was her role and, if she accepted that it was, how she could rightly speak about that experience.

Nanko-Fernández describes her dilemma this way:

Too often there is a temptation – even in the best of intentions – to move from solidarity with an other to a misguided assumption of commonality such that the other's agency is usurped. In other words, my good intentions, our shared humanity, and my particular experience of you and with you can lead me to believe that I can represent you and in turn speak for you and in your place. The result is a denial of agency for those who are being represented, reinforcing their under-representation. The challenge is whether it is possible to exercise a posture of what I would call ortho-proxy, a term coined here to express the posture of rightly and responsibly representing another (Nanko-Fernández, 2010:39).

My situation is not the same as that of Nanko-Fernández. I am not in a position where I am regularly asked to speak on behalf of immigrants. But, we who are part of a global non-profit that works with churches in 88 countries globally often share stories of the work these churches are doing (Global Strategy n.d.). And, even more recently, our organization has started to share stories from around the world on a podcast called "A World of Good" (Tatman and Gale 2020). Sharing these stories has led me to ask the question of whether we were speaking rightly on behalf of those with whom we partner around the world. If not, how do we begin to create filters that assist us in ethical storytelling?[2] There are many hindrances to sharing stories in ways that rightly represent the other, such as unexamined cultural bias and a tendency toward oversimplification. But there are still opportunities to share stories that inspire action and involvement in ways that honor and edify those with whom we work.

Clearly a framework is needed for storytelling that can aid in how stories are communicated. With that framework, offered next, come three important principles, utilizing Nanko-Fernández's writings in conversation with other theologians, to move toward orthoproxy.

Framework for Storytelling

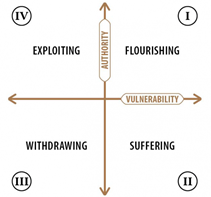

As Global Strategy has attempted to engage in orthoproxy, i.e., right speaking on behalf of another, we have looked for a framework to help process the stories we tell. We believe the problem with storytelling comes down to power. Those telling the stories have power over those whose story is being told. There is a power dynamic that is unfairly slanted toward those who advocate. As we began processing that dynamic, I came across Andy Crouch's book Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk and True Flourishing. In the book, Crouch wrestles with two concepts and their interrelation: authority and vulnerability. His writings offer a framework to analyze our stories. It is important to note that no framework will be all-encompassing in terms of analyzing the ethics of a story. The goal is not to find a one-size-fits-all framework, but to provide something that allows each story to be analyzed through the lens of power.

Crouch defines authority as the capacity for meaningful action and vulnerability as exposure to meaningful risk. Crouch also makes the distinction that authority is always conferred on a person (Crouch 2016:35-40).

With these definitions in mind, Crouch places these concepts on a quadrant, as seen in the image above (Crouch 2016:27). Quadrant one is where there is high authority paired with high vulnerability, which he defines as flourishing. Quadrant two, directly below quadrant one, is where there is low authority and high vulnerability, which he defines as suffering. Quadrant three, to the left of suffering, is where there is low authority and low vulnerability, which he defines as withdrawing. Finally, quadrant four, to the left of flourishing, is where there is high authority and low vulnerability, which he defines as exploiting.

Often when we tell stories, it is easy to be in the position of high authority and low vulnerability. For example, if the story is not about us, it is easy for us not to have any vulnerability with telling the story and be in a place of power as the storyteller. In these cases, we are often telling stories about other people which makes them high in vulnerability (experiencing meaningful risk) but low in authority (no opportunity for meaningful action). As the storyteller, it seems the only option to share a story without eliminating the authority of another is only to share our own story (putting ourselves in the place of vulnerability). Though sharing personally is something that should happen, there are dangers with that as well. For instance, we can make ourselves the hero or, if not the hero, we may be the center of the story with characters and action revolving around us. The alternative, it seems, if we move away from ourselves being the center, is simply to avoid telling stories of global work for fear of exploitation. Or, can we find ways to give authority to the person whose story we are sharing?

Three Principles

In this final section, I bring together Nanko-Fernández's concept of orthoproxy paired with Crouch's authority/vulnerability quadrant and offer three principles that aid us in telling honest, compelling, and more socially aware stories. The three principles are to (1) tell stories in the midst of long-term relationships, (2) value language, and (3) allow those whose story is being told to edit their story.

The first principle is to tell stories in the midst of long-term relationships. One of the first things we often try to do in telling captivating stories is to tell the story as if it were complete. This attempt arises partly from our need to simplify, but we also need to prove something is effective by showing a story that begins in a place of destruction and ends in a place of redemption. The problem is that, when we tell a story, we are often only telling a small part of the story but portraying the story as if it were complete. This selective and incomplete story-telling inevitably takes the story out of context.

In a beautiful book cataloguing her work with refugees in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, D. L. Mayfield shares the struggles and successes of caring for her neighbors. Mayfield is careful not to share stories as if they were complete, but instead she opens a window into the lives of those with whom she is connected. At one point, Mayfield shares about some friends who have been working for years in the most diverse neighborhood in the United States. She writes, "They have watched as people's testimonies went up and down the scales, as addictions and families and lies turned the static conversions into actual lives. They have seen stories as they really are: long-term and full of miracles and crushing disappointments, a constant tale of being saved and relapsing back into ourselves" (Mayfield 2016:87). By contrast, the stories we tell often are only portions of whole accounts. If we craft those stories in such a way to pull out only the parts we want to show, whether intentionally or unintentionally, we not only miss the beauty in the entirety of God's work, but we falsely claim a reality that is simply not true.

On a practical level, our stories must be told within the midst of relationships. Mayfield goes on to write, "We, the do-gooders, stay for a short while, because we crave the knowledge that we have done some good in the world. And we leave before we have a chance to see how poor in relationships we really are" (Mayfield 2016:88). The stories we tell should be grounded in long-term relationships. They should reflect deep involvements in people's contexts. The stories should recognize the history that has come before and that there will be more story that follows, whether it is captured in our telling or not. We must get better at understanding the larger context so we can locate the stories we want to tell within the larger story (Katongole and Rice 2008:49). How long have we been in relationship with the person whose story we are going to tell? Are we taking only part of their story to share? Are we putting too much emphasis on certain elements of their story? Life is complex, and sharing stories that minimize that complexity in order to drive home a point can do emotional harm to both the person in the story and the listener.

The second principle is that language matters. One of the most challenging aspects of composing a story is finding appropriate language. As expressed earlier in this article, many millennials care about language. They care about the way someone speaks about another person. They are sensitive to generalizations and are often aware of power dynamics. Nanko-Fernández reminds us that "Even the creation of space for marginalized voices to speak or be heard is not unaccompanied by undertones of privilege" (Nanko-Fernández 2010:46). The way we talk about those we work alongside, internationally or domestically, matters. Furthermore, even when we attempt to utilize language of equality, we must explore the unintentional privilege we express.

One example of language that challenges is the use of us/them language. Though we may not mean to create boundaries between ourselves and those we work alongside, the way we tell stories often makes sharp contrasts between our home culture and the culture in which we work. The use of us/them language may help connect the reader/listener with the storyteller ("I am like you") but can also inadvertently create false distance between those from another cultural background. This is not to say that there can be no discussion of differences between cultures, but often making clear-cut cultural distinctions is carried to an extreme to heighten the impact of a story. Even the way we categorize the characters of a story (those being served versus those serving) can perpetuate us/them understandings and distance.

On a practical level, taking language into account means we must edit our stories with language and power dynamics in mind. Using Crouch's quadrants, we need to process where we are exerting power and how to balance our authority with vulnerability. Who is the hero in the story? Is it the person we are sharing the story about or ourselves, our church, or our organization? Are there places where we utilize us/them language? Are we intentionally or unintentionally heightening differences?

The third and final principle is that our stories must be shared with (and edited by) those about whom we are sharing. Leroy Barber tackles issues of racism and injustice in his book Embrace: God's Radical Shalom for a Divided World. Barber offers some challenges to the way we advocate for those on the margins. For instance, in his writing Barber does not use the phrase advocate "for" (an important language distinction), but instead talks about advocating "with." He writes,

Trust has to be earned, and that can be done in many ways. One of the ways I think best is through advocacy: speaking with marginalized people as they seek justice. Justice sought alongside someone on the margins because of race, economics, gender, or nationality is a powerful tool when done in partnership with them. Advocating with friends is a transformative process for everyone involved (Barber 2016:104-105).

Similarly, Nanko-Fernández offers us a challenge to read within the context of community to avoid misinterpretation (Nanko-Fernández 2010:37).

On a practical level, before we publish or preach stories that are not our own, we should request the input and correction of those for whom we are speaking. One of the reasons this does not happen more often is that it takes time. It takes time to ask for feedback. Maybe the story is written in another language than that of the person who needs to offer correction. Maybe the person is in a remote location and difficult to engage. If such hurdles stand in the way, then it may be advantageous for us seriously to consider whether or not the story is worth sharing. Christine Pohl discusses the unique challenge she has faced when she has taught on offering hospitality to the marginalized and there are marginalized people present. She remarks that it changes the way we talk about those we serve when we know they are sitting in the pews where we are preaching and teaching (Heuertz and Pohl 2010:41). How would we tell this story if we were telling it with the person present? Have we offered the person in the story the opportunity to edit and correct the story before it is shared? Have I asked their permission to share the story?

Conclusion

We who are in the United States live in a culture that values individualism and consumerism, so we must be cautious that our stories do not treat our brothers and sisters as commodities for our own end. Indeed, all storytellers must examine how their own cultural values might negatively portray, impact, or exploit those who are being described. How we share our stories matters.[3] As Soong-Chan Rah writes, "The acquiescence to consumer culture means that churches fall into the vicious cycle of trying to keep the attendees happy. When a church entices consumers by using marketing techniques and materialistic considerations, is it possible to change that approach after the individual begins attending the church" (Rah 2009:55)? How do we make sure we do not fall into the same individualistic or consumeristic mindset?

Storytelling is an artform requiring incredible care and time. In order truly to tell stories that captivate a listener without disempowering those we serve, we must become better and more vigilant storytellers. Carmen Nanko-Fernández puts the onus on us:

While much attention has been given to bringing the voices of marginalized individuals and communities to the table, less has been done to shift the burden of responsibility to those who must do the hearing and attending. If we are to be ethically responsible, then we must take care to listen so as not to misrepresent what is being said or to reinterpret it through the lenses of our own agendas (Nanko-Fernández 2010:46-47).

It is with this heart for the voice of the marginalized that we must engage in ethical storytelling.

References

Barber, Leroy (2016). Embrace: God's Radical Shalom for a Divided World. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, an imprint of InterVarsity Press.

Carlson, Elwood (2008). The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. Springer Netherlands.

Clark, Natalie A. (2007). "An Exploratory Study of the Millennial Generation's Acceptance of Others: A Case Study of Business Students at a Private University." Ed.D. Dissertation, Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology.

Crouch, Andy (2016). Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk and True Flourishing. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, an imprint of InterVarsity Press.

Feldman, Derrick (2017). "The Rise of a Generation's Voice" The 2017 Millennial Impact Report, Phase 2: Power of Voice: A New Era of Cause Activation and Social Issue Adoption:ii. Achieve and The Case Foundation. Available online at https://www.themillennialimpact.com/sites/default/files/reports/Phase2Report_MIR2017_091917_0.pdf (accessed April 7, 2020).

Gale, M. Andrew (2018). "Practicing Justice: Justice in a Millennial, Wesleyan-Holiness Context." Ph.D. Dissertation, Asbury Theological Seminary. Available online at https://place.asburyseminary.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2441&context=ecommonsatsdissertations (accessed April 7, 2020).

Global Strategy (n.d.). Global Strategy website, www.chogglobal.org (accessed January 31, 2020).

Heuertz, Christopher L. and Pohl, Christine D. (2010). Friendship at the Margins: Discovering Mutuality in Service and Mission. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books.

Howe, Neil (2015). "Why Do Millennials Love Political Correctness? Generational Values" Forbes website, https://www.forbes.com/sites/neilhowe/2015/11/16/america-revisits-political-correctness/#bd0d5082de73 (accessed April 7, 2020).

Howe, Neil and Strauss, William (2000). Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation. New York: Vintage Books.

Katongole, Emmanuel and Rice, Chris (2008). Reconciling All Things: A Christian Vision for Justice, Peace and Healing. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books.

Kinnaman, David and Hawkins, Aly (2011). You Lost Me: Why Young Christians Are Leaving Church . . . And Rethinking Faith. Grand Rapids, MI: BakerBooks.

Kling, Fritz (2010). The Meeting of the Waters: 7 Global Currents That Will Propel the Future Church. Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook.

Mayfield, D. L. (2016). Assimilate or Go Home: Notes from a Failed Missionary on Rediscovering Faith. New York, NY: HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Nanko-Fernández, Carmen (2010). Theologizing en Espanglish: Context, Community, and Ministry. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

Offutt, Stephen, Bronkema, F. David, Murphy, Krisanne Vaillancourt, Davis, Robb, and Okesson, Gregg (2016). Advocating for Justice: An Evangelical Vision for Transforming Systems and Structures. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

Pew Research Center (n.d.). "Comparing Millennials to Other Generations" Pew Research Center website, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/03/19/comparing-millennials-to-other-generations/ (accessed December 31, 2015).

Pontier, Scott and DeVries, Mark (2017). Reimagining Young Adult Ministry: A Guidebook for the Ordinary Church. Ministry Architects Publishing: Ministryarchitects.com.

Rah, Soong-Chan (2009). The Next Evangelicalism: Releasing the Church from Western Cultural Captivity. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books.

Rainer, Thom S. and Rainer, Jess W. (2011). The Millennials: Connecting to America's Largest Generation. Nashville, TN: BH Publishing Group.

Raymo, Jim and Raymo, Judy (2014). Millennials and Mission: A Generation Faces a Global Challenge. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library.

Steensland, Brian and Goff, Philip, eds. (2013). The New Evangelical Social Engagement. Oxford University Press.

Tatman, Nate and Gale, M. Andrew (2020). "A World of Good – A Global Strategy Podcast" Global Strategy website, https://www.chogglobal.org/aworldofgood/ (accessed April 7, 2020).

Thomas, Gena (2017). A Smoldering Wick: Igniting Missions Work with Sustainable Practices, 2nd ed. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Wuthnow, Robert and Offutt, Stephen (2008). "Transnational Religious Connections" Sociology of Religion 69(2):209-232.