Overcoming “Domination”: A Vulnerable Approach to

Inter-cultural Mission and Translation in Africa

Jim Harries

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, July 2020

Abstract

This article considers how the African mission field can be a level playing field for Westerners and locals. Mission presenting of the gospel must be contextually appropriate. Choice of language is a part of this. Use of English as global language today is different from use of Greek in New Testament times. This article shows how terms can travel between cultures with or without their ‘cultural roots’. Local cultural characteristics, such as the prominence of witchcraft in much of Africa, should not be ignored. Africa in the 1970s called for a moratorium on Western mission. This article considers the implications of this not having happened. Western education is found to create an ‘island’ of knowledge in Africa. Vulnerable mission is proposed as the way forward, keeping Western missionaries on the ground.

Key Words: Africa, contextualisation, education, globalization, mission

Introduction

This article uses insights from pragmatics, which considers the meaning of language as derived from its context (Harries 2007:32), to address issues of financial and linguistic domination by the ‘West’ in the African Christian mission field. It shows how contextual issues are being ignored in widespread processes of translation. A careful consideration of contextual translation issues in the light of the current global context and culture leads to certain suggestions for ways to reform missionary practice. Missionary practice as here advocated is to be transformed from one in which the role of the West is primarily that of a donor and expert translator into one in which some Western missionaries can join non-Western Christian ministers in furthering their God-given tasks ‘hand-in-hand’ on a level playing field.

Choice of Language

A rapidly globalising world is bringing new challenges to inter-cultural translation in, amongst other places, the church. This article examines the nature, needs, and shortfalls of this communication process and proposes necessary changes to how it is to be engaged in the days ahead.

Missions scholars do well to note peculiarities of Paul’s contexts that may not apply today. Peoples of the Mediterranean basin under the Roman Empire, about which Paul moved, had a long history of trade, contact, and interaction. Human aspirations and disputes had caused numerous wars and skirmishes between them over many centuries. All this resulted in similarities in ‘culture’ from one part of the region to another. This situation is unlike, I suggest, much of intercultural mission today. While the impact of activities in the Mediterranean basin and Middle East had a profound effect on the people of Western Europe, and in turn the American continent (all of ‘the Americas’), the same cannot necessarily be said for the entire globe. The Far East took a different direction. Latin America was found to have diverse and varied cultures on the arrival of the Spaniards and Portuguese in the sixteenth century. Australian Aborigines, so called Primal peoples in other parts of the world and especially the people of sub-Saharan Africa, had remained largely ‘cut-off’ from developments in the so-called ‘civilised’ world until recent history. As a result, cultural chasms being crossed by inter-cultural missionaries today are vast by comparison to those faced by Paul and his companions in New Testament times.

If Paul’s sermons varied according to the nature of his audience, and his audience was less varied than are ‘audiences’ today, then presumably today’s sermons should be more varied than were Paul’s. Paul realised that there was no point in citing endless Old Testament texts when speaking to the gentiles in Athens (Acts 17:22-31), and he did not make reference to unknown Greek gods when speaking in Jewish synagogues (for example see Acts 13:16-41). Paul was able to make such adjustments to ways in which he translated his messages to the degree that he was familiar with both ‘worlds’. He clearly could not have spoken intelligently to Athenians if he had no clue about Athenian ways of life and philosophies.

Similarly, presumably, missionaries today need to direct what they say according to the contexts into which they speak. This suggests the need for theological texts (written as well as spoken) that are suited to a context. It suggests the need for locally rooted rather than universal syllabi for theological education programmes and preachers / teachers. These needs seem to run contrary to recent trends in which U.S.-American theological content is prescribed internationally, without translation.

Parallels are often drawn between the role of English as ‘global language’ today and Greek as international language in New Testament times. Similarities are indeed evident; Alexandria’s expansive occupations ensured a widespread adoption of Greek, which also served to carry Hellenism around the known world of the time. The Roman Empire added Latin to the mix but took advantage of Greek as well. This process is in some senses comparable to the way that the USA’s global ambitions take advantage of the wide spread of English that was brought about by the prior spread of the British Empire.

The differences between the way that Greek was spread and used in New Testament times and the way that English spreads and is used today are less often considered. These differences are many, diverse, and I believe of critical importance in looking at inter-cultural translation. Many of these differences arise from ‘advances’ in technology that have occurred since the days of the Greeks. Literacy was in New Testament times very limited. Communication was therefore predominantly oral. Even where written documents were circulated, the communication of those documents and the reception of their contents would have been mostly oral. Oral communication was limited to face-to-face contact situations. There were no electronic loud-speakers. There was no radio, television, or telecommunications network. There was no formal universal educational system. Even for written communication; there were no photocopiers, and there was no printing press, never mind fax machines, telegrams, postal service (except perhaps of a very basic nature) and certainly no Internet. That is to say, there was no digital or printed means of written communication whatsoever. Hand-written documents were carried and copied by hand.

I believe that the above constraints to the spread of a language are very significant. Greek was spread by word of mouth, by real people who were actually present in flesh and blood, typically to individuals or small groups of people, or occasionally one supposes through means of amphitheatres to crowds of a few thousand. Why am I emphasising this point? Because whereas the Greek language in biblical times was spread in connection with Greek (or non-Greek) cultures and ways of life, English has in more recent generations, particularly through developments in communication technologies, in a way that is less connected to any culture or way of life.

It is clear that languages usually have cultural roots attached; in addition to ‘simple meanings’, words also carry connotations, known in the field of pragmatics as implicatures (Leech 1983:153). Recent studies in linguistics no longer consider implicatures to be the fuzzy edges of words, like static interfering in a radio broadcast or the difficulty one may have at identifying people who are walking at a distance until they draw nearer. Rather, implicatures are seen as being the very essence of communication. (For an example in relevance theory, see Sperber and Wilson (1995).) This recognition of the central role that implicatures play in communication raises many questions for the process of translation.

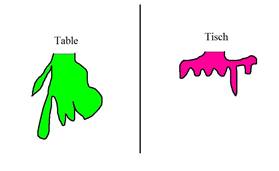

Options in translation can be illustrated with some very simple diagrams. Take the word ‘table’ and its translation into the German Tisch. Figure 1 illustrates the English word table in comparison with the German word Tisch before the process of translation has occurred. While in a sense it is true that Tisch is a translation of table, it is also true that the roots of these two terms are different. They have some very different implicatures in usage. For example, the apparently compound German Nachtisch would seem to translate into English as ‘after-table’, but in fact the English equivalent is ‘pudding’ (dessert). In one sense, then, for Germans tables are a part of their conceptualising of pudding in a sense that is not at all the case in English.

English person German person

Figure 1: Table and Tisch and their Roots, illustrating differences between words that translate each other

Note that the implicatures of the term ‘table’ (illustrated by its ‘roots’) in Figure 1 are different in shape from those of the word Tisch. Below, Figure 2 demonstrates an example of a German person who learns English with the roots of the words learned:

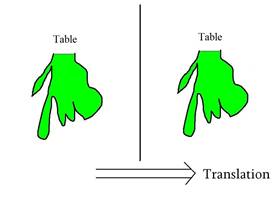

English person German person

Figure 2: Translation of a Word and its Roots

This German person knows that the English word for Tisch is table and also comprehends the roots of that English word. This is, I suggest, the way someone is able to learn a language ‘holistically’. This is a way of learning from someone face to face or, even more importantly, while able to observe the life of the person from whom one is learning the language. A German person who came to live in England and learn English in interaction with English people would learn English in this way. That person would acquire the contextual roots (and the context here could be far and wide – including linguistic context, physical context, social context etc. etc.) at the same time as learning the ‘phonetic-translation’ of the German word Tisch as being ‘table’. This is the kind of language learning that would have gone on in New Testament times with Greek.

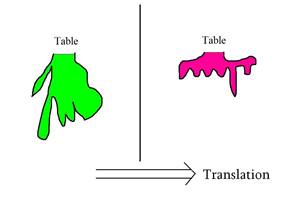

Figure 3 below illustrates an alternative option for language learning:

English person German person

Figure 3: Learning the Translation of a Word without its Roots

In this case, the German person has heard or been told that ‘table’ is the English word for Tisch. Yet, all the roots of the English term table, as assumed by the German, are actually the very roots as were there for the German word Tisch. This kind of learning is what occurs from a textbook, through the Internet, through a radio programme – in order words, at an impersonal distance. Such learning of a language is not being able to observe the way of life of the owner of the language from whom one is learning. This process results in super-imposing a foreign grammar and phonetics over the roots of the language being learned.

Although the diagrams above are clearly simplified, they do graphically illustrate two different ways of understanding a translation, namely with or without implicatures. For the purposes of this article, the latter means of translation to or from English (Figure 3) is especially widespread and common in today’s world, whereas the former (Figure 2) was common for translating Greek in New Testament times. This difference has arisen for some of the reasons mentioned earlier, especially in terms of the technology available for communication. Furthermore, today’s common means of translation have many and serious implications for functionality and mutual understanding between the peoples concerned. The epitome of the translation in which roots are not carried in translation is, of course, the use by a country (or church) of a language other than its own for its own purposes. Once, for example, an East African country begins to make use of English for its own affairs, its people will inevitably use English words as translations of their own terms, i.e., on the basis of the assumption that the English words have ‘indigenous’ (African) roots.

Here is another example to try to illustrate this point. Let us imagine that a U.S.-American preacher illustrates his message through reference to a barbecue. This U.S.-American was cooking sausages so as to give his friends hot dogs on a winter evening at a party celebrating his birthday. A translator into the African context with which I am familiar would have a difficult task in the following areas:

- Why is he (the preacher is a man) cooking, when cooking is a task for the ladies?

- What is a sausage?

- Why are people being given dogs, and in what sense are the dogs hot?

- What is winter?

- How were the friends going to get back to their homes when it is too dangerous to walk around in the dark?

- Why are Christians having a party and not a worship service?

- What is a birthday, and why is it being celebrated?

Because of these points of confusion, a translator might say, “The American’s wife was cooking meat for people to eat, and this was extraordinary because one does not usually eat outside at the time of year when it is so cold that (this cannot really be explained), and these people would later get home as they all – though you might find this difficult to believe –had their own cars, and they were celebrating the anniversary of the day the man’s mother gave birth to him (which is a strange American custom).” (The advent of the smartphone and recent spread of the Internet has resulted in a much greater global awareness of American ways of life than used to be there. The principles being put forward here however still apply.)

Here is a question worth considering: what would happen if the above were not translated? Clearly, on the assumption that the visiting preacher is a man of God, the people’s understanding of the above would have to be such as to fit within their context of what a godly preacher should do. Because men do not cook, the meaning of cooking could be ‘purchased’. Giving people hot dogs – well, Americans are known for their habit of giving out money, so ‘hot dogs’ is presumably a strange way of talking about money. A winter evening – probably he meant to say ‘Wednesday’ and not ‘winter’ but was misunderstood. His birthday obviously refers to Christmas, known to be the day on which we commemorate the birth of Jesus. In this instance, English is being appropriated into an African cultural context. If we were then to create a dictionary, we would conclude that:

‘Cook’ is used to mean ‘purchase’,

‘hot dogs’ is a name for ‘money’,

‘winter’ is another name for ‘Wednesday’, and

‘birthday’ is a way of referring to ‘Christmas’.

This is the kind of English that many African people nowadays use, once the official language of a country has become English. Such use of English makes it difficult for foreigners (to Africa, i.e., in the present discussion native English speakers) to ‘make sense’ of what is going on. They will not know that ‘hot dog’ is a way of talking about ‘money’, for example.

In today’s globalised world, foreigners (i.e., native English speakers) come to have more and more of a say in the way that English is used in Anglophone Africa. This is especially the case in countries whose educational systems are based on ‘foreign (British) English’, i.e., in most if not all of Anglophone Africa (Kanyoro 1991:403). This imposition of “native English” can force local people to use a language that is less and less integrated into their own context.

Amongst the assumptions made by the Western world in its relationship with Africa is that the economic system in Africa runs similarly to that in the West. If this were the case, then indeed it would make sense to give (i.e., to translate) the same economic ‘advice’ in Africa as one does in the West. But do African economies work in the same way? Not according to several authors (Harries 2008:23-40; Maranz 2001).

One feature of many African economies that distinguishes them from Western ones can be illustrated as follows. Many African people are amazed at how oblivious Westerners often are to witchcraft. Indeed, many Western missionaries do not even acknowledge the presence of witchcraft, which is a position that bewilders African Christian brothers and sisters, who labour daily under the influence of witchcraft. As to what witchcraft actually is, a reality that Westerners say they are not aware of, a simplified but helpful description is that the powerhouse of witchcraft is envy that has an inter-personal force (Harries 2012). The fear of envy, Maranz points out (in slightly different words), is rampant on the continent of Africa (Maranz 2001:139). One outcome of the fear of the envy of others is that people are reluctant to accumulate wealth unless everyone else is doing so at the same time. An instance of a time when ‘everyone’ (e.g. all farmers) acquire wealth simultaneously is at crop harvest. At other times, though, many people are very wary of acquiring wealth. Contrary to widely held assumptions of profit maximisation, African people may prefer to minimise profit to avoid having wealth when others do not have it, and so to avoid becoming the victims of envy, i.e. witchcraft attack.

One prerequisite for economic development on the African continent, according to the explanation above, is a reduction in envy, i.e., a reduction in witchcraft. However, such an analysis begs the question of how Western texts that are related, even obscurely, to economics, are to be translated. If witchcraft is compared to a brick wall preventing progress down a road of economic prosperity, then the direct translation of a text on economics from the West into an African setting is like instructions to keep driving down the road regardless of any brick walls barring the way.

In order to advocate indigenous advance, how a reduction in witchcraft can be achieved is needed. Such a reduction can be achieved when people have faith in God. This is one key reason why promotion of faith in God is a key prerequisite to African development. Should such a ‘key prerequisite’ be included in the process of translation of Western texts as a kind of inevitable addition? In other words; shouldn’t then the translation into African contexts of economic textbooks from the West include instruction on how to overcome witchcraft? This point will be further explored below.

African churches have long laboured under some of the kinds of misunderstandings illustrated above. Westerners have had expectations of African Christians that have been highly impractical, and these Africans have been obliged to use languages that make little sense to them. At the same time, they are constantly being plied by money and gifts of various types from the West; these ‘gifts’ come with various strings attached that represent conditions that frequently make little sense and may be impossible to fulfil.

Churches in Africa have responded to the pressure of working with such ‘strings’ in different ways. To classify these responses in perhaps over-simplistic terms, mission churches (founded by missionaries who are not Pentecostal) persist in giving the appearance of following directives from the West and keep other important activities going on ‘the side’. Pentecostal churches follow traditional African means of acquiring their needs through spiritual means but using such Western symbols as clothing and language. AICs (African Indigenous Churches) reject much Western symbolism and understand the use of such physical items as robes, candles, water, oil, and crosses to be means of getting the power to satisfy their needs. Put differently, mission churches attempt to take translations of theological texts from the West as they are, Pentecostal churches appropriate them, whereas indigenous churches reject them.

The next section considers ways in which Western mission efforts have attempted to adjust to the issues just described, albeit unclear about the roots of those issues.

Why Mission from the West has become Short-term and Money Focused

Two trends are particularly noticeable in mission from the West to Africa in recent decades. One is that mission has become increasingly donor-focused. Another is that Western mission has withdrawn from the front-line, often by becoming short-term. (Short-term missions have been much discussed. For how they make missionaries less vulnerable, see Henry 2014). Both of these trends have contributed to there being reduced contextual-sensitivity in Christian mission in recent years.

The end of the British Empire was marked by a growing wave of independence of African states from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s. This marking of the end of Empire clearly also caused missionaries to re-consider their position. Part of this ‘reconsideration’ resulted from an African call, led by Gatu in Kenya, for a moratorium for mission in the early 1970s (Kendall 1978:86-107). The Africans concerned with this moratorium were calling for Western missionaries to ‘go home’. In many ways, historians tell us, that call did not succeed. Western missionaries did not all get up and go. The fact that such a call was made, however, and that it received such wide acclaim is surely significant, and the call must have been cause-for-thought for many a missionary on the field. Presumably also, because the moratorium was not fulfilled, some of the problems in African churches that were being anticipated by those who called for the moratorium may now be coming to pass.

There has been and still is a widespread feeling that the mission task of Westerners in Africa has been completed (Kendall 1978). Many missiologists are guided on this point by the practice of the apostle Paul. Paul’s practice appears to have been to start a church, appoint leaders, and then move on (Acts 19:21-22). The Bible and more specifically the book of Acts closes with churches apparently ‘growing by themselves’; new churches seem to be ‘left alone’. So there is one missiological school of thought that says that recently planted churches should be ‘left alone’.

In reality, however, they were never ‘left alone’ in Paul’s day, and they should not intentionally be ‘left alone’ today. Churches planted by Paul continued to interact with other churches and Christians, and certainly in today’s world intercultural international church relationships continue apace.

The 1960s that saw the end of empire in much of Africa coincided with a great deal of missions activity. Much of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century missions experience, being in the context of empire, was an experience of domination. When domination was no longer possible in that classical sense, mission was in need of new direction. That new direction – doing mission from a position of vulnerability and weakness – has been hard to find. This article is seeking to point to that way of conducting mission.

With the end of colonialism has come the end of ‘colonial adventure’. Dreams of ‘conquer and exploration’ have lost their pertinence. European populations have moved on to other things. One of those things seems to be, more than in any other era, comfort. The West has developed its own comfort, e.g., health care, longevity, safety, and wants to share such with others. As a result, the missionary message has recently been re-interpreted or retranslated in many ways so as to become a message of ‘how to live a long and comfortable life’. While such a description may seem unnecessarily provocative, that way of stating the matter accurately portrays one aspect of the recent trend of trying to combine ‘development work’ with mission, sometimes even to the exclusion of the latter. This contentious issue, often considered as ‘evangelism verses social action’, is of course much debated and need not be pursued further here.

The decline in ‘religious belief’ besetting the West extends its effects to those who remain active in churches. That is, the orientation of Christian believers can be ‘less religious’ than that of believers in previous generations whose neighbours and colleagues were less hostile to the very foundations of Christianity. Christian belief in the West generally has come to be of a lower intensity, or “...diluted modern versions of Christianity...” (Larner 1984:114). The tenets of historical materialism, and more generally rational rather than spiritual causation, are given the most prominent roles. Missionaries are less inclined to sacrifice their lives for ‘spiritual principles’ when apathy and doubt with respect to the same have a high profile even in their own communities.

A rise in the prominence of material values (or a decline in faith in the spiritual) has contributed to the emergence and prominence of holistic or integral mission. Unheard of until recent decades, advocates of the above have through re-interpreting the Scriptures come to insist that ‘gospel preaching’ go hand in hand with economic development, health care, and other material benefits. The gospel alone is no longer considered sufficient (Harries 2011:83). This reconfiguration of what constitutes “mission is more of a change in terminology and justification rather than a change in practice, as mission from the West to Africa has always gone hand in hand with education and health services.

Another important factor in the decline of Western mission is the ‘guilt’ of the capitalist West. Guilt and implied guilt result in increased donor activity, but the desire not to be seen as imperialistic or authoritarian has brought a preference for being ‘hands-off’. That is, an increasing ‘withdrawal’ of Westerners from the front line of mission into support and donor roles enables people to feel (presumably) less responsible for any negative impacts of their activities. Delegating more power into indigenous hands presumably can result in a minimisation of some otherwise offensive or deleterious impacts of outsiders – but not without other implications, as explored in this article.

The Changing Nature of ‘Received’ Mission

Changes in the practice of mission combine with changes in the lived context of mission recipients. The non-actualisation of the 1970s moratorium marked the beginning of a new era for African churches. Outsiders had made it clear that they were not going to allow the whim of African people to force them into an exodus. Missionaries from the West were not going to ascribe their hosts with the authority to refuse their approaches. This was not only a refusal of Westerners to give up membership of and participation in African churches. It was rather, in effect, a refusal to give up on having a controlling power over churches in Africa, and beyond.

This situation coincided with a revolution in communication and with an enormous historically-unprecedented expansion in Western economies. The influences of contexts from which the moratorium sought relief have, as a result, been increasing geometrically. Direct links between African churches and individuals in the West, outstripping traditional relationships brokered by mission-agency professionals with wide inter-cultural experience, have added to the tendency to engage in mission short-term from a position of relatively little understanding. Additional factors, such as the widespread knowledge of Western languages in Africa that bypass traditional translation processes, have resulted in a general amateurisation of mission. Misunderstandings often put money flows, that have become a much larger part of basic survival in a fast developing world, at risk. Strategies continue to be developed in Africa that are designed to enhance the lucrativeness of relationships with the West. Corruption and lies have by this stage become the norm – even though these are hardly even noticed by the more pragmatic amongst donors of funds.

As a result of the above scenario, African Christians have been forced to consider how to co-exist with their determined foreign bed-fellows. They could not refuse their influence, but how was the influence of a paying-guest to your home who refuses to leave when asked to be handled? The money received can of course be useful. The answer on how to handle the donating foreigners thus becomes, in order to ensure the continuation of funding, to exclude donor-visitors from more sensitive contexts that they could otherwise misunderstand.

When, as at present, money is ‘pushed’ onto Africa without translation by a people who have a limited grasp of local contexts, something really has ‘got to give’. That which ‘gives’ is often truth. When there is a growing band of ready takers, as is assured by booming African educational systems in Western languages, the avoidance of truth, should there be a risk of its interfering with ongoing money flows, has become more and more of a norm.

The type and scale of translation confusion described earlier unfortunately aggravates the mis-communications that are already happening as a result of the position with finance just described. For the article to consolidate its several different points, it is important to comprehend the overall impact of the particular matters that have been taking place.

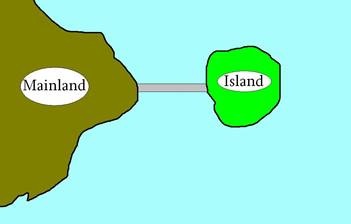

One ‘overall impact’ of the multitude of inputs coming from the West to African Christians can be termed the creation of an ‘island of knowledge’. This island constitutes knowledge from the West that is valuable because of the relationship that it engenders with the West, but that knowledge is relatively disconnected from associated indigenous bodies of knowledge. That is, African people are creating an island of understanding that is separated from their innate life comprehension by an intermediary space (represented here by water) that is navigated with some difficulty. Such an ‘island of knowledge’ is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 4 below:

Figure 4: Depiction of an Island of Knowledge

The ‘mainland’ in this illustration refers to African people’s implicit understanding of life, themselves, and the world, i.e., an African worldview. This worldview is a kind of unity of thought that has arisen and been passed on through many generations. The ‘island’, on the other hand, represents understanding acquired as a result of formal education and Western missionary teaching. The water in-between illustrates that, while the two are clearly cognizant of each other, the indigenous African worldview and Western-acquired knowledge are at the same time also distinct and separate. It is that distinction and separation that is both very interesting and very problematic. Conceptually, many African people can choose to function either on ‘the mainland’ or on ‘the island’, and those two bodies of thought are largely disconnected.

Language-translation does not necessarily aid, and certainly does not resolve, this issue. The current basis on which translation from one language to another occurs is the substitution of new words for original ones, as discussed earlier and illustrated in Figures 1 to 3 above. In short, translation that should be a process of communication between different contexts is these days frequently treated as a substitution of different words in an attempt at reproducing the original text. (While it could be argued that the above is appropriate for Bible translation, it does not follow that it is appropriate for the translation of all other texts.)

The dream of the West, as well as some Africans, is that Africans should abandon the ‘mainland’ – or at most keep some its ‘interesting’ and ‘exotic’ features - and develop only the ‘island’ (abandon their traditions and become Westernised). In reality, however, such a dream does not materialize. An alternative analogy that could help us better to understand this situation would be that of two liquids, e.g., a blue liquid (the West) entering a yellow liquid (Africa). If blue liquid mixes with the yellow liquid, then the outcome will not be bits of blue liquid in yellow liquid. It will rather be a green liquid! No matter how much blue liquid is gradually added, the colour of liquid in the glass will never be truly blue (Harries 2010:373-386). Africa will never lose its African character so as to become identical to the West. Instead, Western inputs into Africa will always be transformed on entry. Such transformations may well work against the originally intended functions of the Western inputs. Translation is called for, but is it actually happening?

Therefore, this article arrives is a three-part interim conclusion. One, for African people, Western understandings can resemble an island with minimal links to most of the thought-world that makes up their innate way of life. Two, the ‘island’ will never be purely ‘Western’ but will be influenced by African people’s innate ways of thinking. Three, while the island is made up of conceptual materials that are translations from the Western ‘mainland’, it will never replace the African-thinking-mainland. The mainland will be influenced by the West but will never lose all its African flavour.

Vulnerable Mission

I believe that God knows how he will ‘rescue’ African churches from the dilemmas mentioned above that they currently face. God will do it using his people from various ethnicities. The major role is surely to be played by the African people themselves. I pray indeed that their searching of the Scriptures be guided by God’s Spirit and result in the glorification of God’s name. But I also believe that the foreigner has a role in God’s church and that churches should all be open to receive Christians from other parts of the world.

Because there is a role for foreigners, I believe that there is a place for Western mission in Africa, as well as for international and inter-cultural churches. I believe that there is a role that can be played by Western missionaries in Africa, even today. I believe that this role must be a ‘post-colonial role’. Such an appropriate role can be described as ‘vulnerable mission’. That is, I suggest that some Western missionaries engage their key ministries, or at least a key ministry outside of the West, using local resources and local languages (Vulnerable Mission n.d.).

I do not believe that the African missionary task is complete, or that the era during which missionaries can be sent to Africa is over. I believe that the role of sending people should always be there, and that the task of encouraging and challenging the church will not end until the return of Christ. This sending role requires, amongst other things, the movement of Christian believers from churches in the West to the rest of the world.

Western Christians who so travel need to realise that the days of empire are over. Empire talked about domination. It is sometimes forgotten that people can appreciate being dominated if the ‘dominated’ as a result acquire an income. A vulnerable missionary avoids domination through controlling purse strings or linguistic privilege. Those things were, I believe, the real ‘problem’ that led to the 1970s moratorium call. If this is the case then a missionary does not have to stay away to avoid all the problems that the moratorium was trying to solve. But he or she should avoid using foreign money and foreign languages. The reason African people did not advocate that for foreign missionaries was – I believe – that they did not believe that Westerners could minister in such a vulnerable way. Can they be proved wrong?

To fulfil the conditions of VM (Vulnerable Mission) in ministry is no easy challenge. It requires a stepping outside of the traditional missionary ‘comfort zone’. But help is at hand! VM talks about one’s ministry and not about one’s lifestyle. It does not dictate what the nature of a missionary’s home-life ought to be. It only says how he or she ought to minister. Sometimes nationals of poor countries have been unhappy with missionaries who have served them while maintaining a standard of living way beyond their local one. The AVM (Alliance for Vulnerable Mission) asks that such people set aside their jealousy and be content with the missionary’s working with them on the same level. Jealousy, after all, is not a virtue but a sin that should not be practiced by true believers (see Exodus 20:17). While a Western missionary in a poor land ought to and will be challenged to live simply, the outworking of that challenge should be left to the missionary, God, and the, missionary’s supporters – and not dictated to them by the AVM (alliance for VM).

Overcoming the West’s predilection to faith in historical materialism, or the implicit belief that effective social change results from the investment of money and use of resources, is another challenge. The ‘fact’ of material cause and effect has so firmly captivated many in the West such that it is extremely hard to escape from it. But ‘escape’ is a must. The solving of problems is never as simple as providing whatever is overtly missing. Alternatives to the provision of ‘material’ are invariably there and must be sought. Translations of texts from the West should presumably allow for such. Here are some examples:

1. A girl’s father throws her out of her home because she has become a Christian. It might seem that a foreign missionary ought to provide a house for her. The best option, however, could be for her to go and beg her father to be allowed to return (Jack 2010:110).

2. Hungry-season food shortages in Africa may appear to require the provision of outside food aid. Realising that people intentionally produce less so as to avoid the witchcraft that arises if they have a surplus while their neighbour is hungry shows that a lasting solution is more likely to consist in undermining the power of witchcraft.

3. An old lady being neglected and hungry may be as a result of her children intentionally avoiding her because they are not ready to forgive her for previous injustices she committed. It is forgiveness and not handouts of food that are here required.

Solutions that advocate non-material provision should be priority for Christian missionaries. Encouraging people to ignore such solutions by simply translating texts that arise from a materialist community into a monistic one is a way of generating and perpetuating misunderstandings and often very unhealthy dependence on outside funds.

If ‘integral mission’ means that a Christian minister should be concerned for the physical as well as the spiritual needs of his flock, it is bang on target. If ‘on the other hand’ it means (which in practice is often the case) that mission efforts must be accompanied by funds from the West in order to be considered legitimate, then such ‘integral mission’ is misleading and potentially harmful. Supplementing evangelism with handouts from Western donors can very soon lead to evangelism being difficult or even impossible without such handouts. The latter hinders (or even prevents) true evangelism from local initiative.

Once again, the important factor of ‘guilt’ must be considered. There is little doubt that guilt currently underlies much activity from ‘the West to the rest’. Guilt seems to be at the root of the widespread supposition that a Westerner living in the poor world must be active in alleviating poverty by sharing resources from the West. This approach continues to be advocated even if introduced resources undercut local markets, create dependency, and cause strife, division, and endless disputes.

Guilt, however, should not dictate Western missionaries’ relationships with those who are poor. Why should people’s relocating themselves geographically automatically add guilt, or the obligation to ‘help the poor’, that was not there before they went there? If there is such an obligation to help the poor when one has moved, then this implies that there is also an obligation to move to where the poor are. If indeed there is an obligation to help the poor, surely that obligation applies equally to all who have the means to help. Does an obligation to help the poor mean that every worker in the poor world must be giving out handouts? Or could it mean, as an alternative, that a portion of the missions’ taskforce can fulfil the bulk of this role on behalf of their colleagues? If an individual missionary can fulfil his/her obligation to help the poor through material handouts by delegation to another missionary, then the former is enabled to interrelate in a way that is more comparable to that of local people, and so to give a life-example that can be imitated by local people.

To re-iterate the above paragraph, what I am proposing is not necessarily that any less money reach the African continent from the West (although that option might be preferable in many cases), but that this money be concentrated in fewer hands. If, for example, there are two missionaries who each raise $100,000 to give to the poor in Africa, one of the missionaries could give that money to the other to give out so that he/she be left free of an identity as ‘donor’ and thus be enabled to relate to African people much more ‘on the level’. Such identity ‘on the level’ enables missionaries to translate implicatures and impacts rather than only words and meanings of texts.

To return to the imagery in Figure 4 above, the process just outlined is a way of concentrating activity on the ‘mainland’ instead of doing it all on the ‘island’. The ‘mainland’, amongst indigenous people according to their indigenous way of life and principles, is the natural arena in which Christian ministry should take hold. This approach is in effect a way, and perhaps the best way, of contextualising the Gospel. This is not a contextualisation worked out theoretically in an ivory tower for later application on the field. Rather, it is contextualisation guided by God that occurs when the gospel is translated so as to be able to meet a particular way of life of a particular people.

The Challenge

The Western church has put itself into a trap in terms of its relationship with churches in the Global South. The trap is essentially a grip on power: the Western Church frequently only knows how to relate to the church in the Majority World from a position of power – which is really a position of domination. Many churches, in Africa at least, are ready to work on that basis, as long as they stand to benefit materially from such an agreement. ‘Passive resistance’ to such domination frequently takes the form of the corrupt misappropriation of funds for non-designated purposes. The failure to engage in contextual translation perpetuates these issues.

One response of the Western church in the light of today’s post-colonial scenario is to withdraw from mission. Another has been to change the shape of mission – from being long term involvement to short-term trips and offering of funds with fewer strings so that ‘misappropriation’ not be visible (and in that sense cease to be a problem for the donors). In terms of translation, the mechanical nature of Scripture translation has been extended to other forms of translation. Or the translation step has apparently been bypassed as a result of African people being taught to engage using the languages of their ex-colonial masters. The above have resulted in today’s scenario whereby African churches remain dominated (in some ways) by ignorant (of local contexts) and absent (largely) benefactors. Such blind domination - since it is impossible actually to do away with strings attached to funds or to translate impacts from one cultural context into another without a close knowledge of the latter culture - bodes badly for the future of the church internationally.

This article’s suggested alternative is a continuation of close involvement through relationship that avoids unhelpful obligations to share materially and thus enables ‘translation’ in the holistic sense of translating implicatures and impacts as well as ‘meanings’. That is, relationship from the West that does not have to be backed up either by material donations or oversimplified translation processes, and relationship from the South (Africa) does not need to include pleading poverty or ignorance. The resulting approach is ‘vulnerable mission’ (Vulnerable Mission n.d.). An important way forward for inter-cultural mission is for some to be engaged using the resources and languages of the people to whom they are reaching in ministry.

Conclusion

Among globalisation’s surprises are some little-explored complexities in inter-lingual relationships. The taking of Greek in New Testament times and English today as comparable international languages for use in church and society is questionable, since Greek tended to be spread orally by ‘real’ people, whereas English is today spread in textual form and using diverse types of technology. Hence the Greek language in those days carried more of its original cultural meaning as it spread than does English today. This article points out how assumptions about the context of the use of words can transform their perceived meanings until they are so different from the original as to be inappropriate for use by people coming from the original context, whether they realise this transformed meaning or not.

The moratorium on mission in Africa that was proposed in the early 1970s not having taken place presumably means, at least in the view of its promoters, that the damage to the African church that was to have been avoided by the moratorium is nowadays occurring. The ‘problems’ that resulted in the moratorium call arise, it is here suggested, not from the very presence of Western missionaries itself, but through their being financially over-endowed and linguistically naïve.

Missionary teaching these days, increasingly rooted as it is in issues concerning ‘development’ communicated through Western languages, has resulted in ‘islands’ of knowledge in people’s minds, that are largely disconnected from their daily lives. An escalating rate of partnerships being developed with African churches, in which Westerners invariably take the role of donor, is these days accelerating the development of these islands; and, because of their disconnect with the rest of life, these islands appear as if they will never fully meet the needs of African people. The temptation to enter the power-trap of rooting ministry in financial donations and simplified translations, often motivated by guilt on the part of Westerners for consuming an over-large proportion of global resources, must be addressed by having some Western missionaries operate on the basis of vulnerable mission principles. In conclusion, at least some Western missionaries must carry out their ministries in the ‘poor world’ using local languages and resources.

References

Evangelical Fellowship of Canada (2005). “The Code of Best Practice for Short-Term Mission” World Evangelical Alliance website, https://www.worldevangelicals.org/resources/view.htm?id=58 (accessed June 18, 2020).

Harries, Jim (2007). “Pragmatic Theory Applied to Christian Mission in Africa: with special reference to Luo responses to 'bad' in Gem, Kenya.” PhD Thesis. The University of Birmingham. Available online at http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/15/ (accessed June 22, 2020),

_____. (2008)., ”African Economics, and its Implications for Mission and Development in Sub-Saharan Africa” Journal of the Association of Christian Economists 38 (January):23-40.

_____ (2010). ”Translation and the Language of Implementation of Third-World Development – a Study on Sustainability in Africa” Journal for Sustainable Development in Africa 12(3):373-386.

_____ (2012). “'Material Provision' or Preaching the Gospel: reconsidering holistic (integral) mission,” in Jim Harries, Vulnerable Mission: Insights into Christian Mission to Africa from a Position of Vulnerability. Pasadena: William Carey Library, 81-98.

_____ (2012). "Witchcraft, Envy, Development, and Christian Mission in Africa" Missiology: An International Review 40(2):129–139.

Henry, John (2014). “What Can Vulnerable Mission Contribute to the Short-term Missions Discussion?” Occasional Bulletin Spring, 27 (2):15-17.

Jack, Kristin, ed. (2010). The Sound of Worlds Colliding: Stories of Radical Discipleship from Servants to Asia’s Urban Poor. Coventry: Servants to Asia’s Urban Poor.

Kendall, Elliott (1978). The End of an Era: Africa and the Missionary. London: SPCK.

Larner, Christina (1984). Witchcraft and Religion: The Politics of Popular Belief. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Leech, Geoffrey H. (1983). Principles of Pragmatics. London and New York: Longman.

Maranz, David (2001). African Friends and Money Matters: Observations from Africa. Dallas: SIL International.

Musimbi, Kanyoro R.A. (1991). “The Politics of the English Language in Kenya and Tanzania,” in Jenny Cheshire, ed., English around the World: Sociolinguistic Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 402-419.

Sperber, Dan and Wilson, Deidre (1995). Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Second edition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Vulnerable Mission (n.d.). Vulnerable Mission website, http://www.vulnerablemission.org/ (accessed June 22, 2020).