The Culture Tree:

A Powerful Tool for Mission Research and Training

Mark R. Hedinger, Terry Steele, Lauren T. Wells

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, July 2020

Abstract

This article introduces a model of cultural analysis based upon the organic nature of a culture, called the “Culture Tree.” Culture is an integrated system of ideas, actions, authorities, and unseen presuppositions. These elements of people groups work together to create patterns that can be analyzed and understood with the appropriate tools. Just like cultures, trees have different elements that are integrated into a living, growing organism. The “Culture Tree” model seeks to provide a tool to demonstrate the integrated nature of cultural elements similar to integration within a living organism.

Mission training and mission strategy both benefit from models of patterned interactions that occur within people groups. Thus, the model seeks to accurately reflect the structure, organic nature, and complexity of cultures. This article will also demonstrate the accuracy of the model and its usefulness to culture training and mission planning.

Key Words: culture, Culture Tree, model

Introduction

Mission training and mission strategy both benefit from models of patterned interactions that occur within a group of people. The closer the model reflects reality, the more effective it can be in providing guidance for ministry.

This article is an introduction to a model of culture that we call the “Culture Tree.”[1] The model is based on the physical characteristics of a tree and is an analogy that proves to be quite powerful and accurate when applied to various aspects of culture. The article is designed around a simple outline that will describe why modeling is important, compare other models of culture that are used in ministry situations, and then explain in detail the Culture Tree as we use it in our training organization (CultureBound n.d.). After that explanation, we will consider the accuracy and usefulness of the model. Our intention in this article is to provide a new and highly effective model for teachers, trainers, and mission strategists to use in their analytical and educational programs.

We will begin with some important definitions. Enoch Wan and Mark Hedinger define “culture” as the patterned interaction between Beings/beings (Wan and Hedinger 2017). This definition reminds us that people groups are affected by interactions with God, and that the triune God also has patterns of interaction.

We will base this article on what Wan and Hedinger call “horizontal relationships” (Wan and Hedinger 2017). Horizontal relationships exist between created beings – for the purposes of this article, between people. Horizontal relationships are different from vertical relationships which include both created beings and the three Persons of the triune Creator.

The Culture Tree, then, is a model for understanding the patterns of relationships that exist within and between human communities. Though God is certainly present in these relational patterns, we are limiting our discussion to the human members of any given group in order to simplify the introduction of this model.

The Importance of Models

Culture is a heuristic concept. That is, it is a concept only; it does not exist in any physical, measurable sense. One cannot go to the store to buy a pound of culture. One cannot measure the amount of “culture” per se. One can only create analogies and models that represent the factors that make the concept salient.

A further complication for understanding culture is that culture represents the patterns of a people group that are enculturated from generation to generation. Intergenerational teaching is aimed at the youngest members of the group: at the people who have no point of reference with which to compare the patterns of their own people with patterns of any other people. The result is that the patterns that one learns as a child become standards by which all of life’s expectations are measured. The patterns are learned by trial and error at such a young age that they become deeply ingrained habits. One does not need to think about how to respond to a given situation. These “intuitive” responses have been learned through the trial and error of childhood and adolescence.

The very nature of culture, both seen and unseen, makes it necessary to use models or analogies in order to understand the structure and function of culture. The challenge is that an analogy is only helpful to the extent that it reflects the nature of actual reality. In the case of an analogy or model of culture, we believe that the Culture Tree can significantly contribute to the understanding of the structure and function of culture.

Contemporary Models of Culture

There are three primary models currently used to represent the nature of culture. The first is the anthropological model (Hofstede 1997; Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner 2014) that divides culture into numerous components and then describes each of those components. For instance, a culture may be analyzed in terms of achieved status or ascribed status, as well as in terms of individualist focus rather than collectivist. Those traits (achievement/ascription dominance and individualism/collectivism) are clearly important in culture studies, and this model is beneficial in examining how varying degrees of explicit and implicit culture patterns represent important patterns of behavior and thought. At the same time, the anthropological model is limited to understanding culture as a series of binary characteristics and, if used as the sole model of culture, can lead to under-discussing other important characteristics. The anthropological model is limited as it does not express the fluidity and interconnectedness of culture.

A second model of culture is the iceberg (Hall 1989). The iceberg shows that there is more to culture “under the water” than just what is observed “above the water.” The patterns of a culture, in other words, include both visible actions and events and, at the same time, invisible elements that undergird those visible parts. This model illustrates that many of the patterns of behavior of a people group are based on invisible traits such as values or beliefs. Those invisible yet massive components are key to understanding what is visible. The iceberg model graphically demonstrates that important parts of a culture rest below the surface. However, the model’s weakness is that it does not illustrate the various layers of culture that lay both above and below the surface.

A third model is the onion (Smith 1992). According to this model, culture has an invisible core outside of which are other layers that are influenced by that core. This model has the ability to subdivide a culture into components such as organizational administration, values, beliefs, and views of history. The onion model of culture, along with similar layered models (Hiebert 1985; Schein 1985), excel as tools for analysis of culture in a stable, static form. Notably, however, onions are inert once harvested. The onion model is thus limited in effectively illustrating a strong sense of life and connection to other objects.

Important Characteristics of an Accurate and Useful Culture Model

What then should be included in a model of human cultures? We would suggest that an accurate and useful model of human culture will both incorporate general traits that all cultures share and allow for particular values, beliefs, and behaviors that various cultures exhibit. The model will also illustrate the complexity of relationships and social structures within a culture as well as the process of growth and change within culture. Finally, an accurate and useful model of culture will be able to illustrate the potential interactions between distinct cultures.

The Culture Tree Model

This article suggests then that the Culture Tree Model exhibits the characteristics needed for an accurate and useful model of human culture.

General Traits of the Culture Tree

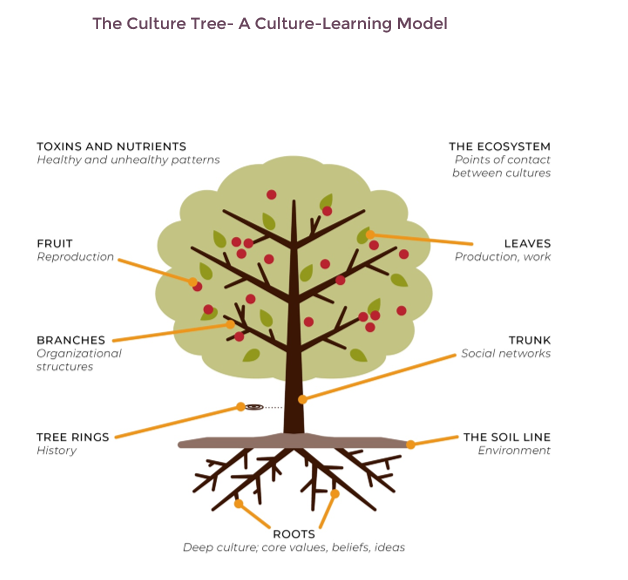

The diagram below shows nine aspects of physical trees that represent cultural patterns, as described further below.

Roots – values, beliefs and expectations that are not in plain sight.

Arguably the most important aspect of cultures (as noted by both the iceberg and the onion) is that cultural patterns are not random. The patterns we observe in the life habits of any people group can be seen in the invisible truth statements, beliefs, values, and expectations that the people share. The roots of a tree provide this analogy.

In a recent study done in the rain forests of Panama (Sinacore 2017), scientists measured the biomass of root systems in a forest. The invisible, buried roots accounted for a full 28% of the total tree biomass. The root system extended, on average, to a distance as great as the distance from the trunk at ground level to the crown of the branches. Roots, in short, contribute extensively to the mass of a tree. In a tree, those roots provide support, nutrition, and hydration.

In a culture, the invisible beliefs (what is true), values (what is important), and expectations (what is normal) are represented by the roots. When an outsider is learning an unfamiliar culture, an important part of the process is to discover the “worldview” of values, beliefs, and expectations. When those invisible traits are understood, it is more likely that existing structures and habits will make sense, and it is also more likely that changes or introductions to the culture can be presented in acceptable ways. For example, when an U.S.-American university student seeks to build a relationship with a Chinese colleague it is helpful to understand U.S.-American individualism and Chinese collectivism, and that U.S.-Americans tend to make friends one at a time while Chinese tend to make friends in groups.

The Soil Line

Trees have an invisible part and a visible part. The soil line is where that break is. The soil line is also where contact with the physical and living environment is the most noteworthy. The soil line is also a place where pests and disease can intrude.

Cultures come in contact with the greater context in many places, but it is always helpful to recognize the places where a culture interacts with its environment. Patterns of life in desert cultures will be different from patterns of life in a sea-going people. The physical environment is one critical element to analyze when we think of a group of people, since climate affects the necessary activities and resources that are available to a people group.

Branches and Organizational Patterns

Rising from the soil line we find a main trunk that has branches which come directly off of that trunk. Any culture will have the need for organizational patterns. Those are represented by the branching that we see on the Culture Tree. For example, there are culturally acceptable ways to organize the workplace: perhaps it is under the direction of a chief or boss, perhaps it is more independent and individual. The organizational patterns will overlap so that schools, medical facilities, and businesses all demonstrate largely the same sort of organizational preferences. The values and beliefs of the roots will give shape to the branches and trunks that are visible, “above ground.”

Interaction with Other Cultures – Ecosystem

One of the interesting characteristics of trees is the variation possible in how much they interact with their surroundings. Trees in a savannah grassland may be very far from other trees and in fact might be surrounded by a relatively small number of other organisms. On the other hand, in forest situations trees interact with their environment and with other trees at many levels: roots intertwine, branches touch, and animals can jump from one tree to another. In human terms, the isolated cultures may have relatively few encroachments from other human groups. In more densely populated parts of the world, though, the patterns of one group of people will be influenced by and interact with the patterns of nearby neighboring cultures. In large cities, populations from many cultural groups may literally be on the same block. While the patterns of each group will be distinct, there is also a relative ease for interaction.

Leaves – The Production of the Culture

The photosynthesis that takes water and CO2 from the atmosphere and generates sugars for the energy needs of the tree takes place in the leaves. The shape of those leaves varies from the needles on pine trees to the differing leaves found on deciduous species. The important point is that trees interact with the environment which leads to the production of nutrition that sustains life. Geert Hofstede speaks of the cultural values that he calls “masculine and feminine” (Hofstede 2010). The difference is what sort of value those differing cultures place on differing kinds of production. Masculine cultures focus their energy on factory output and military expenditures, while feminine cultures prefer medical and educational production for the wellbeing of their population. The point is that there are values involved in the production that takes place within a culture.

Fruit – What Is Prepared and Passed to the Next Generation

Trees also are involved in replication. Some tree species can start new life all alone (monecious); other species require two trees to produce fruit and viable seeds (dioicous). At any rate, tree species that survive have ways for each generation to give rise to another. Human cultures have the same need. Some of those cultures can meet all of the needs for advancing the next generation by themselves. Other cultures end up “exporting” and “importing” people in order to survive from generation to generation.

Besides the analogy of how flowers and fruits are produced, there is also the important issue of values that can be seen when we talk about cultural reproduction. The values of a people are probably most strongly seen in what they teach to their young. The stories, corrections, truth statements, and other carriers of values are informally but very carefully passed from generation to generation. When a younger generation refuses to carry out the traditions of the elders, great cultural strife can result.

Pathways within the Culture– Water and Nutrient Conduction

Within a plant, there is a series of specialized tissues that draw water and other material from the roots to the highest points of the leaves, then allow the descent back to storage tissues. It is not a system that can be mapped easily. There is movement within the tree, but it is not a simple matter to view how that movement takes place.

Cultures are similar. Communication, decision-making, leadership, parenting, and teaching patterns are just a few examples of the pathways that vary greatly from one culture to another. The Culture Tree gives an analogy of complex pathways that exist within the living organism. Cultures, too, have complex pathways through which important resources flow.

Environmental Sensitivity – Toxins and Nutrients

Trees have a level of health or illness that may have to do with internal issues (genetics, for example) but also is highly influenced by the environment. Small amounts of trace minerals can make the difference between a healthy plant and an unhealthy plant. Toxic materials in the soil or water can create harm. Nutrients like nitrogen can provide sudden growth.

The cultural patterns of a people are also impacted by even small amounts of social toxins or social nutrients. As an example, within some cultures people teach and lead one another on the basis of a set standard of right and wrong – they see the world through guilt/innocence. Imagine a neighboring nation that teaches and leads on the basis of shame/honor. The guilt/innocence nation can easily say things or make gestures that would bring shame to their neighbor. One nation feels it deeply; the other is not aware that any offense has taken place. What is a “non-issue” to one is a toxin to the other.

Differing susceptibilities to economic ups and downs are also part of this environmental sensitivity. Worldwide economic difficulties will have more impact in some cultures and less impact in others. The variations have to do with many factors, including level of economic connection with other nations and cultures. Those that are more isolated may weather the storm of economic ups and downs more easily than economic systems that are tied tightly to international markets.

Growth, Change, and Adaptability – Tree Rings

The last of the Culture Tree components has to do with the fact that trees have a life cycle. Though much longer, in general, than the life cycle of people, a healthy tree will grow, slow in its growth, senesce, and eventually die.

The life cycle of a tree is recorded in its tree rings: over the years there is a change in the girth of the tree. That growth can be seen in what we commonly call the “grain” of the wood. Alternating layers of tissue permit the nutrient capacity of the tree to expand as the physical size also expands. The history of the tree is “written” into those bands that we call “tree rings.”

Cultural patterns of people groups are constantly growing and changing rapidly throughout their lifespan. Models of culture that reflect this growth pattern are able to show the organic patterns of a people group. Knowing how a given group of people pattern their corporate changes and how they permit for the growth of new initiatives is a significant part of cultural analysis.

The Accuracy of the Model

Earlier in this article we suggested that a healthy model of culture will be able to exhibit that, while cultures differ in values, beliefs and behaviors, all cultures share general traits. A helpful model will also illustrate the complexity of relationships and social structures within a culture as well as the process of growth and change within culture. Finally, an accurate and useful model of human culture will illustrate the potential interactions between distinct cultures. The model in other words must demonstrate unity, diversity, complexity of relationships, growth and change, and interactions with other cultures.

Unity: The Culture Tree allows us to see interaction between cultures even as we see the varying ways that cultures take care of needs that are common to all humanity. All peoples need food, water, and a means for reproduction. The Culture Tree lets us see how those universal needs are met through individual patterns within a given cultural group.

Diversity: The Culture Tree is based on the idea that, just as there are diverse kinds of trees that still are properly called “trees,” there are also many cultural approaches to meeting human needs. There is great diversity in how cultures meet human needs.

Complexity of Relationships and Social Structures: There are few direct lines between such realties as government patterns, economic structures, and religious organizations. Yet those and many other subsections of a culture are clearly interactive. The Culture Tree allows us to see the complexity of social structures within a given culture, while also noting the patterns that are part of that culture.

Growth and Change: Human cultures are not static. The Culture Tree model allows for shifts and changes: there is a root system that brings stability and nutrition, and yet that root structure also permits growing and changing both at the root level and in the visible, upper level.

Interactions between Cultures: What happens in one culture will impact other cultures. Globalization has increased market interactions as well as the spread of illnesses and the diffusion of technology. Nations are in contact with many other nations, and somehow the model we choose for understanding human cultures needs to allow for that interaction while at the same time understanding the characteristics of the culture itself. The Culture Tree model allows for that perspective of cultural interaction.

The Usefulness of the Model

The CultureBound training program has used the Culture Tree as a model for training for several years now. We find that it has a number of strengths:

It permits us to talk about the sociological elements that are regularly recognized as part of a culture. We can talk about history, organizational structures, invisible values and beliefs, production, and reproduction. The tree allows us to see the complicated patterns of a culture in light of common but flexible elements.

The Culture Tree provides us a tool for learning about a new culture. If one is sent to minister and/or work in an unfamiliar culture, the Culture Tree can be a helpful guide to analysis and discovery. At times we have used the phrase “culture map” to talk about simple discovery of the common elements found in the layers of our Culture Tree. Seeing those cultural elements graphically represented across the outline of a tree helps to recognize how the organizational patterns, history, education, productivity standards, desires for future generations, and other cultural realities all attach to the invisible roots.

It also permits us to create teaching and discipleship tools that deepen biblical impact on people’s norms, standards, and experiences of the people. In short, the Culture Tree is more than just an analytical tool: it also facilitates discernment of the Holy Spirit’s work among people groups. At CultureBound we use the Culture Tree every time we have a training. The Culture Tree allows culture learners to gain experience in training contexts that they later carry to their intercultural situations.

One of the most flexible parts of the Culture Tree is that it can be used successfully by children as well as adults. In fact, CultureBound began using this model after a children’s book on the Culture Tree was published by one of the authors of this article (Wells 2018). As families transition from one culture to another, one of the great strengths we see for using the Culture Tree is that parents and children can together explore a new way of life using the culture tree as their guide. For young children, that exploration may involve just the invisible and the visible (roots and leaves). For older teens, it may include analysis and culture mapping much like we have suggested for adults. The model allows for use at many different levels.

Conclusion and Findings

This article has presented a tool for culture learning that we have found to be very effective. While no model is as complete and accurate as the actual reality being depicted , in the case of a concept as complex as the heuristic we call “culture,” it is very helpful to have a model that shows unity, diversity, internal complexity, contextual sensitivity, and the possibility of generational growth. We would recommend the use of the Culture Tree for course work in missions, anthropology, sociology, and many subsets of those disciplines.

References

CultureBound (n.d.). CultureBound website, https://culturebound.org/ (accessed May 19, 2020).

Hall, Edward T. (1989). Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor Books.

Hiebert, Paul G. (1985). Anthropological Insights for Missionaries. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Hofstede, Geert (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Intercultural Cooperation and its Importance for Survival. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational Culture and Leadership: A Dynamic View. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sinacore, Katherine, et al. (2017). “Unearthing the hidden world of roots: Root biomass and architecture differ among species within the same guild” PLoS ONE 12(10): e0185934. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185934.

Smith, Donald K. (1992). Creating Understanding: A Handbook for Christian Communication Across Cultural Landscapes. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

Trompenaars, Fons and Hampden-Turner, Charles (2014). Riding The Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Wan, Enoch and Hedinger, Mark (2017). Relational Missionary Training: Theology, Theory & Practice. Skyforest, CA: Urban Loft Publishers.

Wells, Lauren (2018). Cora’s Culture Tree. Portland, OR: CultureBound.