An Investigation of the Social Identity of

Muslim Background Believers (MBBs) in Bangladesh in Light of the

Set Theory, Critical Contextualization, and Self-Theologizing Teachings of Paul Hiebert (Part I)

Peter Kwang-Hee Yun

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, July 2020

Abstract

This article investigates the social identity of Muslim Background Believers (MBBs) in Bangladesh. The author narrates the historical context of MBBs in Bangladesh up to the present day with a particular emphasis on four MBB social identity groups in Bangladesh taken from Tim Green’s writings: Christian, Isai, Isai Muslim, and Muslim. Through using the qualitative case study method, the author selected three MBBs whose cases provide significant representation across each social identity. He deals with questions in three areas: new social identity formation, social integration, and Four-self dynamics in Bangladeshi Jamaat (house church or a small gathering of MBBs). Each subject interacts with Paul Hiebert’s three well-known theories: Set theory, Critical contextualization, and Self-theologizing. Through using simple figures and tables, the author tries to explain and incorporate various viewpoints of contextualization in a real context. The findings and implications of this research call for understanding and cooperation between each social identity group and between foreigners and Bangladeshis to foster a healthier future for the MBB community in Bangladesh.

Key Words: contextualization, insider movements, MBBs (Muslim Born Believers), Paul Hiebert’s theories, social identity

Introduction

To start with my personal journey, holistic poverty alleviation was the concept and motivation that drew me to come to Bangladesh. Since my initial short-term visit in 2008, the vision to fulfill both the physical needs of one of the poorest countries in Asia and the people’s spiritual needs (90% Muslims, 9% Hindu, and 0.3% Christian) has made me eager to learn and travel throughout this country. During several years in Bangladesh as a cultural learner and researcher, I have been focused on friendship and participation in the realities of life of Muslim Background Believers (MBBs) here. The context of spiritual hardship from the Muslim majority’s pressure and of physical needs is the starting place in the contextualization discussion in Bangladesh, one of the most fruitful but also controversial fields among Muslim majority countries. Edward Ayub, one of the MBB leaders in Bangladesh, reveals his unpleasant feeling that Bangladesh has been used as “the laboratory and parade ground” of insider ideology (Ayub 2009: 21).

“The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14, NIV). Since Jesus’s Incarnation and Pentecost, the gospel of Jesus Christ has been delivered across cultures. The gospel, which is transcultural and not culturally relative, also “must be expressed from within culture” (Gililand 1989:28; Hiebert 2009:31). Due to two key characteristics of the gospel—translatability (across cultures) and indigeniety (within cultures)—the tension between the universal truth of the gospel and these two characteristics has always existed up to the current globalized mission era. The term “contextualization” reveals this tension as well as the effort for the gospel to break through across cultural boundaries (Moreau 2005:321). For understanding and developing modern missiology and mission work, contextualization has become one of the most significant concepts and practices in current missions.

Contextualization as both concept and practice brings to the surface many kinds of questions from different contexts. In considering Darrell Whiteman’s three functions of contextualization—communicating cross-culturally, criticizing cultures, and creating community (Whiteman 1997), we must consider how to determine what is appropriate contextualization. In practical current missions, “the need for contextualization” by Muslim background believers, inquirers, and mission practitioners has been recognized and discussed (Woodberry 1989:283). There are reports of growing numbers of Muslims who have been drawn to faith in Christ worldwide by Bible reading (sometimes by reading the Qur’an as well), a dream or vision, faithful friends’ witness, or the power of prayer in the name of Isa (Jesus). As diverse as the ways and means through which MBBs have dedicated their lives to Christ, there is an equally great range in varying expressions of their faith.

Due to the diverse ranges of MBBs’ expressions of faith, as is now widely known John Travis, a Christian mission scholar and practitioner, published a wide range of perspectives on Christ-centered communities in the Muslim context called the C1-C6 spectrum (1998:407-408; Travis and Woodberry 2010:30):

C1 – Believers in traditional Christian fellowships where worship is not in the mother tongue;

C2 – Same as C1, but worship is in the believers’ mother tongue;

C3 – Believers in culturally indigenous Christian fellowships that avoid Islamic forms;

C4 – Believers in culturally indigenous fellowships that retain biblically permissible Islamic forms, but not identifying as Muslims;

C5 – Muslim followers of Jesus in fellowships within the Muslim community, continuing to identify culturally and/or officially as Muslims, though a special kind;

C6 – Muslim followers of Jesus in limited, underground fellowship.

The spectrum tries to address diversity differentiated by language, culture, and religious identity. Among the six categories, the characteristics between C4 and C5 have proven to be the most controversial; and, among the three factors distinguishing C4 and C5, the religious identity issue has been seen as the most crucial (Parshall 2003:71-73; Green 2013b:62).

However, this article wishes to assert that “contextualization” is not the most appropriate category to understand the struggle facing local MBBs, even though it is for foreign practitioners seeking to understand indigenous believers and their community. “Social identity” is a more accurate and practical phrase for describing the complex reality MBBs confront in their actual life as a religio-social minority. Their minority status includes MBBs’ efforts to contextualize both foreign practitioners’ and Bangladeshis’ Christian teaching in Bangladesh.

In order to examine Bangladeshi MBBs’ challenge of social identity, this article interacts with paradigms and theories developed by Paul Hiebert to help understand and diagnose this reality, especially biblically. Three theories proposed by Paul Hiebert are employed for engaging several alternative paradigms as well as for understanding the reality of the social identity of Bangladeshi MBBs. The three theories are set theory, critical contextualization, and self-theologizing. Hiebert (1994) provides three frameworks in “Set Theory” — Well-formed sets [Bounded sets], Fuzzy sets, and Centered sets that are helpful for analyzing the situation and phenomenon of MBBs in Bangladesh:

Well-formed sets [Bounded sets] have a sharp boundary. Things either belong to the set or they do not. The result is a clear boundary between things that are inside and things that are outside the category.

Fuzzy sets have no sharp boundaries. Categories flow into one another. For example, day becomes night, and a mountain turns into a plain without a clear transition.

Centered sets [are] created by defining a center… [and] have two types of change inherent in their structure: entry or exit from the set (based on relationship to the center), and movement toward or away from the center (Yoder, Lee, Ro, Priest 2009:180).

With these three “sets” concepts, Hiebert’s two other concepts (1985) are used for this article’s analysis of the data:, “critical contextualization” enables interaction between the text of Scripture with a particular context in order critically to move forward to new contextualized practices; and, self-theologizing allows younger churches to interpret the Bible for themselves and in their own contexts.

The article consists of three parts. The first part explains the historical context of Bangladeshi MBBs’ problems of social identity. Three research questions explore social identity on both personal and community levels. The second part of the article presents a theory of social identity and its interaction with Bangladeshi contexts based primarily on some recent research by Tim Green. The third part details the research data analysis along with three selected MBBs’ case studies, all the while focusing on the three central concepts of new social identity formation, social integration with the majority, and social identity with their own believers’ community. The findings will be examined in light of Paul Hiebert’s ideas and theories. The conclusion will deal with missiological implications for mission practitioners and indigenous believers.

The Historical Context of Bangladeshi MBBs

In the context of Bangladesh, there were very few Muslim converts to Christianity until the 1970s. This was because Christians came mostly from a Hindu background under the influence of William Carey’s outreach and Bible translation for Bengali Hindus. These converts had a strong adhesion to their former religion and culture (Croft 2014:39). Because the initial formation of Christian identity in Bangladesh took on a distinctly Hindu cultural shape, Muslim converts were sometimes required to adopt Hindu cultural forms and regulations as verification of genuine conversions, such as changing their names, using Hindu-dialect Christian terminology, and even eating pork (Taher 2014). These kinds of behaviors by Muslim convert Christians met a hostile reception from their family and community and often resulted in expulsion. Those ‘exiles’ wandered among churches and foreign missionaries for their survival (Johnson 1999:25).

This pattern has diminished since the 1970s due to a few local converts resisting the pressure to follow previous examples and several foreign missionary organizations passionately reaching out to Muslims outside of the existing traditional Christian churches. Despite their goal to build culturally relevant and spiritually sincere communities, the gap between cultures of the existing churches and Muslim converts was too great. For this reason, several foreign mission agencies have tried to build an MBB community separate from traditional churches so as to allow Islamic cultural forms and to encourage the MBBs to remain within the boundaries of family and community (Johnson 1999:27-31).

Another crucial reason for the formation of separate communities between traditional Hindu-background Christians and MBBs was the birth of a new Bible translation in Mussolmani (“Muslim’s”) Bangla, the Kitabul Mokaddos (Kitab) (“the Holy Books”). This new version has been published and distributed since the late 1970s with the assistance of a foreign organization passionate to reach out to Muslims in their heart language (Jennings 2007:24). Along with the use of the Muslim friendly Bible, Jamaats (house or small church gatherings of MBBs) have been started from the mid-1970s. However, because of the lack of knowledge and experience of the leaders of Jamaats, these groups have not been built up to maturity (Taher 2009:1)

Additionally, another turning point in Muslim evangelism has been the initiative of local MBBs outside of the direct involvement of foreigners. After realizing the influence of foreign missionaries’ outreach, the government has started to restrict their outreach toward local Muslims by minimizing the direct evangelistic activities of foreigners and limiting developmental work through registered NGOs. Conversely, these restrictions on foreigners helped local MBBs own their responsibility to reach out to their Muslim neighbors. The situation has made them more proactive in thinking about how locals and foreigners can work together (Johnson 1999:27-31).

However, after the last 30 years of history in the Bangladeshi MBB community, things have not all gone smoothly for two major reasons. Firstly, MBBs have been struggling with their social/cultural positioning/identity in the local Muslim majority society. Some Muslim converts shifted directly to the established Christian church by changing to Christian names and following existing Christian cultures. Some other Muslims wanted to keep staying in the majority community, retaining their religious identity for fear of persecution and sometimes for continued ability to reach out to their Muslim neighbors, whether by their own choice or foreigners’ encouragement. Others are located somewhere between these two margins (Taher 2009:1). All of these MBBs have strived to find appropriate social positions and cultural behaviors such as the use of religious language, religious forms, and participating in important social activities and festivals according to their new faith and identity. Therefore, the issue of social identity is directly connected with contextually interpreting the gospel by deeply considering the religious and cultural forms and context. For them, social identity regarding contextualization has become a significant issue.

Secondly, considering the relatively poor economic situation in Bangladesh, financial factors have always been “a stumbling block” for the MBB society developing maturity. In their daily lives, MBBs have had economic disadvantages, such as finding it hard to get a job and facing difficulties gaining promotions, or losing customers when their conversions are revealed. More importantly, indigenous MBB evangelists have had a tendency to depend on the financial support of foreign missionaries and organizations for their livelihood (Jennings 2007:59). However, funds from outside are not always certain, consistent, or stable. For example, if a church (or several house churches) is (are) planted and a pastor is supported by foreign funding and then the funds stop suddenly, not only does the pastor lose support for livelihood but local MBBs also lose their shepherd. From time to time disputes among local organizations have occurred regarding financial support in evangelistic work. For MBBs, being a self-sustaining faith community is another significant issue.

In several decades of history of the Bangladeshi MBB community, practitioners generally agree that several situational realities exist in which MBBs are immersed. In his presentation for new practitioners, one veteran worker in Bangladesh describes the situation of MBBs in Bangladesh as follows:

1. Evangelism: The gospel has normally been spread first to rural and lower class people rather than to urban and upper-middle class people.

2. Livelihood: Most local MBB pastors and evangelists are dependent on foreign funds.

3. Leadership: There is very little organized biblical training for building up the new generation of leaders.

4. Conflict: Conflict frequently occurs over the extent of contextualization and differing amounts of foreign funds received.

5. Community: It is very hard to find self-sustaining communities and leadership.

6. Network and Partnership: Indigenous partnerships and networks often stop or are severely hampered after only a few gatherings due to conflict (Lee 2014).

This description of the situation of MBBs in Bangladesh can be categorized into four areas: evangelism, funding, leadership, and application of the Bible individually and communally.

These four areas connect directly with the social application of Four-self dynamics: self-propagating (evangelism), self-supporting (funding), self-governing (leadership), and self-theologizing (application of the Word of God in the culture). Researching these Four-self dynamics in the context of Bangladeshi MBBs can be a measure of social dynamics and the future development of their faith community. Researching MBBs’ intention and understanding of the self-propagating (generating) dynamic helps establish the possibility of enhancing the gospel movement continuing beyond the life of paid evangelism. The self-supporting (sustaining) and self-governing (organizing) dynamics connect to the continuity of the next generation of MBBs’ community by minimizing the effect of the uncertain continued involvement of missionaries but maximizing the local initiative of the movement. The self-theologizing (reflecting) dynamic demonstrates how MBBs take the initiative to apply their understanding of Scripture to their own particular Muslim majority society and culture.

As mentioned above, the major problems of social identity and self-sustaining faith communities that Bangladeshi MBBs face are ongoing and not-easily solved. However, these two problems cannot be considered separately. These are interwoven by historical and situational factors in this specific context. The research informing this article incorporates these two issues under the theme of social identity in terms of the individual and community through three areas of questioning: new social identity formation, social integration with the majority, and social identity at a collective level (four-self). The three research questions are as follows:

1. What factors were involved in MBBs coming to identify themselves as followers of ‘Isa? Have the ways in which MBBs identify themselves religiously changed since their conversion?

2. To what extent and in what ways are MBBs integrated into the social and cultural fabric of the broader Muslim community life?

3. To what extent and in what ways do MBBs think their views are different from majority Muslims? Do their views affect whether, or how, they share the gospel with Muslims and their self-standing (four-self) faith community in the long run?

Social Identity Theory and Practice

There is no universal definition of identity among the extensive relevant social science literature (Green 2013a:43). One authoritative resource defines “identity” as having two levels: personal—“the fact of being whom or what a person or thing is”; and, communal—“a close similarity or affinity” (Lexico 2020). Within such a framework, identity cannot be defined only by either selfness or otherness. These personal and social characteristics of identity interact dependently and in conflict with each other (Mol 1976:59). In this sense, most scholars agree that identity has multiple levels.

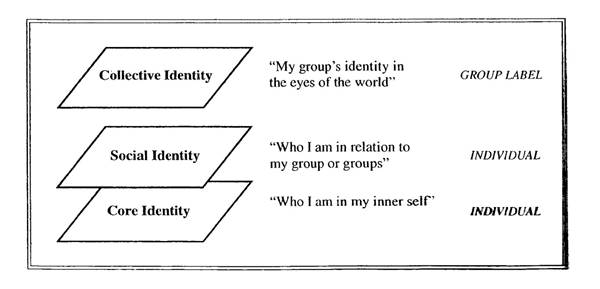

One identity researcher on MBBs, Tim Green, cites psychologist Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi’s book about three levels of identity: collective, social, and ego-identity:

At the top I would place collective identity, i.e. identity as defined by the group… In the middle I would place social identity labels as used by the individual and by others to identify him(self). At the bottom or deepest level I would place ego-identity, which is privately or even unconsciously experienced by the individual (Beit-Hallahmi 1989:96-97; Green 2013a:44).

After synthesizing identity theories and considering the contribution of practitioners, Green presents three layers of identity as core, social, and collective identity (see Figure 1 below) after changing Beit-Hallahmi’s terminology from ‘ego-identity’ to ‘core-identity.’

Figure 1. Identity at Three Levels (Green 2013a:44)

Firstly, ‘core identity’ is an individual level of identity: “Who I am in my inner self?” One example would be a self-identified follower of Isa, who has belief in Isa as Lord and Savior. Secondly, ‘social identity’ is also an individual level of identity but includes the influence of community, family, and friends: “Who I am in relation to my group or groups?” The social identity of MBBs therefore connects to each one’s belonging to either Muslims, Christians, or somewhere in between in relation to their acquaintance with the specific social group. Lastly, ‘collective identity’ relates to how others, for example the majority Muslim community, recognize the groups of believers: as ‘Christian’, ‘Muslim’, or somewhere in between (Green 2013a:45-47).

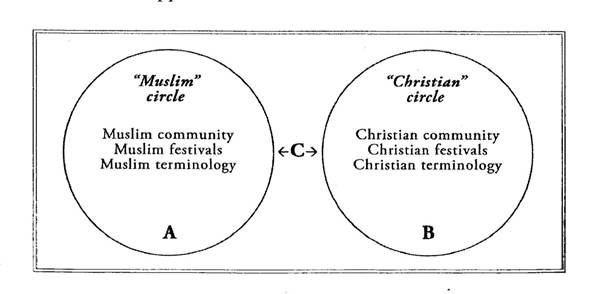

In another article, Green introduces two circles of identity showing two religious boundaries of identity deeply related to the social community and cultural activities (Figure 2):

Figure 2. Circles of Identity (Green 2013b:54)

Figure 2 illustrates two different religious backgrounds including community, festivals, and terminology. Historically in Bangladesh, these two religious communities have hardly shared religious festivals and terminology. Muslims in Bangladesh who came to faith in Christ inevitably experienced a crossing from their former boundary (position A) to the other (B). In the practical situation of new MBBs, however, many are hard to place exactly in one circle or the other. Rather, they say they are somewhere in between (C). Also, MBBs might switch their behaviors and socio-religious identity depending on their surroundings, where they are and who they are with, such as namaz (five times formal prayer daily) and celebrating Eids (two big religious festivals such as fasting and sacrifice), or Christmas and Easter with their two different groups of religious friends. This switching can sometimes be done openly or secretly (Green 2013b:54).

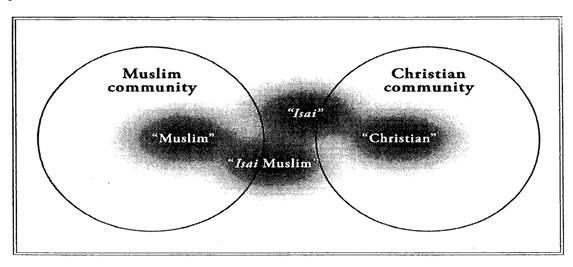

Due to the social and religious complexity of MBBs’ identity in contexts like Bangladesh, Green suggests an alternative categorization with a major focus on ‘social identity’. With the help of a local MBB leader in Bangladesh, Abu Taher, Green has created a diagram advancing discussions of Christ-centered community spectrum called the ‘C-Spectrum’ for the Bangladeshi context. Because of the differences between the historical and social situations of Pakistan and Bangladesh, Green explains that Bangladesh has a more matured MBB community than Pakistan (2013b:62). The diagram below (Figure 3) reflects the “multi-dimensional realities of the situation” and reflects a matured community situation in Bangladesh in contrast with other Muslim majority countries such as Pakistan or Middle-Eastern countries.

Figure 3. Groups of Believers from a Muslim Background in Bangladesh (Green 2013b:60)

Using Paul Hiebert’s concept of “bounded sets,” Green describes the Bangladeshi MBB community as having “more ambiguous social identities and more permeable boundaries” than a “long-established religious community.” All four “fuzzy” groups of MBBs in Bangladesh sometimes “merge and overlap with each other and with the traditional communities” (Green 2013b:61-62). Green’s description of the four groups of MBBs in Bangladesh is detailed in Table 1 below.

|

Christian |

Isai |

Isai Muslim |

Muslim |

|

Completely assimilated in the traditional church |

Close to Christians, but some contacts with Muslims. Switching Christian and Muslim terminology. |

Mostly with Muslims, but little contact with Christians. Most use of Muslim terminology. |

Remain within the Muslim community and follow customs. Two groups: one is cultural; the other is practicing Muslims. |

Table 1. Summarized Characteristics of Four Groups of Bangladeshi MBBs (full version in Appendix A)

The first “Christian” group, who are excluded by their Muslim relatives, incorporates the traditional Christian community and religious activities. The second and third groups, “Isai” and “Isai Muslim,” have varying amounts of contact with Christians and Muslims, with the later more accommodating to terminology and acceptance of the majority Muslim community than the former. The “Muslim” group identifies themselves and others as Muslims regardless of their attendance at Mosque and Eid sacrifice. Interestingly, it is possible to compare Travis’ C-Spectrum with Green’s alternative categorization: C2 – Christian; C3 – Isai; C4 – Isai Muslim; and C5 – Muslim. These two scales are similar, but Green’s view in consultation with an indigenous leader moves one step forward in terms of reflecting contextual details and providing a visual representation.

Research Setting and Three Case Interviews: Interacting with Paul Hiebert

This article employed a qualitative field research method to investigate social identity and social integration of MBBs, using the two research tools of observation and interview. Specifically, the article focuses on three interviews with Bangladeshi MBBs from a wide range of social identity among 48 local interviews and 10 foreigners. Per Paul Hiebert’s guidance, the researcher gave the respondents “considerable freedom to wander” (Hiebert 2009:167) from the questions during the interview and, as a foreign researcher through long-term friendship and observation in past three years, tried not to omit insider (emic) perspectives. Based on Tim Green’s previous research and my research about four (fuzzy) social identities of Bangladeshi MBBs, each research question dealt with Paul Hiebert’s three theories: set theory, critical contextualization, and self-theologizing.

New Social Identity Formation with Paul Hiebert’s Set Theory (RQ1)

|

|

Hasan |

Ahmed |

Rana |

|

Social Identity |

Christian/Isai |

Isai Muslim/Muslim |

Christian/Isai in Jamaat Isai Muslim/Muslim at work |

The three people in Table 2 came to faith in Isa (Jesus) from different gospel proclaimers and methods. Hasan heard the gospel from a Hindu background Christian using the traditional Christian language Bible adapted from Hindu terminology (Hasan 2014). Ahmed was curious about the Inzil Sharif (Gospels or New Testament) when he found a copy in a burning suitcase, but he received teaching about Isa in a one-week seminar that first looks at Isa in the Qur’an, then later in the Kitab (Holy Book) (Ahmed 2014). In Rana’s case, after believing Isa through the guidance of traditional Christians from non-Muslim background and foreigners, he was associating within both boundaries, Christian and Muslim, differently at work and at home (Rana 2014). Concerning simultaneous dual belonging in two communities, Tim Green introduced three strategies: switch, suppress, and synthesis (2013b:56).

Table 2. Three Cases of New Social Identity Formation (full version in Appendix B)

In Bangladesh, a Muslim converted to Christianity oftentimes lives in a state of social confusion and emotional fatigue. In addition, the cultural power of shame in their Muslim society causes these converts to have constant pressure from being labeled as betrayers or enemies of their nation (Meral 2006:510). Both negative effects — extraction and anomie — are interwoven in both personal and public levels, because a Muslim’s conversion is not only a matter of the individual but affects the entire family and community within the culture. Moreover, converts might find it difficult to adjust to their new lives due to negative reactions from the Christian community (Baig 2013:71). It has been for the sake of avoiding the negative effects of extraction that so-called “insider movements” have been taking place. An “insider movement” tries not to “extract believers from their families and pre-existing networks of relationships, significantly harming these relationships” (as happens with the Western “aggregate-church” model) and retain their Muslim identity (Lewis 2007:75).

In his article “Should Muslims Become ‘Christian’,” Bernard Dutch (2000) investigates self-identity issues among MBBs. Dutch argues that Western Christians have a tendency to overemphasize the MBBs’ self-identity and to judge the issue too easily without considering the context. One of the main reasons for avoiding the term “Christian” is that the term, in the place where he served, means “Animist background Christian.” For the people in the village, “Christian” means a practitioner of “the polytheistic path of animism” and a betrayer of family and community. Dutch actually categorizes seven types of believers:

1. Animist background Christians;

2. Christians with Muslim culture (most receive outside funding);

3. Neither Christian nor Muslim (there is no supporting community);

4. Jesus Muslims (Muslims regard it as a disguise for Christianity);

5. Mystical Muslims (Sufi background: regard Jesus as a mediator before God);

6. Muslims with non-mainstream beliefs and practices (compromise several rituals);

7. Full Muslims (remove any trace of difference between themselves and an orthodox Muslim identity) (Dutch 2000:18-19).

Contrary to “Animist background Christians,” “Full Muslims try to fulfill all the pillars of Islam, as they did before coming to faith in Christ. This approach is considered by other believers as syncretistic and undermines any effective witness. Finally, Dutch suggests low profile approaches, which involve “remaining in society; identifying those who are open; appropriately arousing people’s interest; and wooing them toward Christ” as bearing a sensitive witness toward potential believers and maintaining good relationships with family and community (Dutch 2000:19, 21).

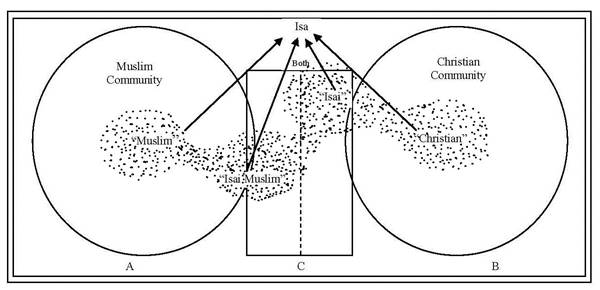

When we apply these findings to Hiebert’s Set Theory (Hiebert 1994), displayed in Figures 2 and 3 above, it is hard to put Bangladeshi MBBs’ current situation into the Muslim and Christian boundaries. Historically, there has existed a clear boundary between Christian communities and Muslim communities, but since Muslims started to come to faith, several “fuzzy” groups have emerged. Phenomenologically, MBB groups in Bangladesh are like a “Fuzzy set community” rather than a well-formed set, because they lack clear boundaries and static characteristics, plus the groups are rather frequently changing. Also, it is very difficult for Isai Muslims/Muslims (left side in Figure 4 below), whose community has been formed over a long period of time, to move to the Isai Christian/Christian (right side) in a short amount of time. Isai Muslims/Muslims groups are also provided social benefits, such as social security, because they aren’t known as an apostate, plus they have the opportunity to draw Muslims to Isa in a relatively less offensive manner. By contrast, the Christian/Isai group has such benefits as a clear converted identity from a Muslim background and the possibility to focus on the Bible and spiritual matters. However, the actual reality of daily life is not very optimistic. The Christian converts feel drained emotionally and financially damaged because of social isolation from family and society, so they have a tendency to find alternative (foreign) supporters. These difficulties and tendencies hinder Christian/Isai groups from continuing to focus on Isa and grow in him. In this sense, centered sets with fuzzy groups can be a possible alternative to encourage people to move toward Isa in the Bible and follow his way beyond strictly bounded sets (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Groups of MBBs in Bangladesh with Centered and Fuzzy Set

In Figure 4, it is more important for each MBB group to have a relationship with Isa than “monitoring and maintaining the boundaries” (Yoder et al. 2009:182). As this article’s case studies have shown, Hasan can be in the Christian/Isai Fuzzy group between B and C; Ahmed is located in the Muslim/Isai Muslim Fuzzy group between A and C; Rana is mostly situated around C — both Isai and Isai Muslim, but he comes and goes between all areas depending on the situation. Rather than flippantly assigning a person to a particular location, the first step should be to show Isa (Jesus) as the center, with everyone moving toward him from every direction. Each group needs to follow “theo-centered directionality” (Baeq 2010:204) or Isa-centered directionality by the word of God rather than focus on certain religious dogmas and regulations. The issue of whether a certain position such as position A is permissible will be dealt with in RQ2 with Paul Hiebert’s Critical Contextualization.

Appendix A – Four Groups of Muslim Background Believers in Bangladesh (Green 2013:59)

|

Christian |

Isai |

Isai Muslim |

Muslim |

|

Completely assimilated in the traditional church with its festivals, language, and social relationships. They no longer have any contact with their Muslim relatives |

Mostly live in the Christian community but preserve a little contact with their Muslim relatives, visit them at Eid and so on. They switch between Christian and Muslim terminology according to the group they are with. Christian tend to understand the need of Isais to compromise in this way; their Muslim relatives view them as heretical but not beyond the bounds of social contact. |

Mostly in the Muslim community but they preserve a little contact with Christians. They use Muslim terminology. Many in the Christian community view them as “fake Christians.” Muslims view them as an odd kind of Muslim, but acceptable within the range of Muslim sects. |

Remain within the Muslim community, follow Muslim customs, celebrate Muslim festivals, and use only Muslim terminology. They have no contact with Christians. They are considered Muslim by the Muslim community and also by the Christian community. There are two kinds in the group: one is Muslim but does not attend the mosque or carry out the Eid sacrifice. They keep full contact with their Muslim relatives, who would regard them as religiously slack but nevertheless Muslim. Believers in this group meet for fellowship with each other. The other is observing Muslims including prayer at the mosque and the sacrifice at Eid. Others around them do not know they are followers of Jesus. And they do not meet up with other Jesus-followers either. |

Appendix B – Three Cases of New Social Identity Formation

|

|

Hasan |

Ahmed |

Rana |

|

Family Background |

Muslim who worked making lungis (male comfortable skirt). Followed most of the Islamic laws. |

Muslim whose grandfather was a Haji (one who was Mecca pilgrim) and father was Imam. |

Muslim family whose mother was working for a Christian pastor’s house as a housemaid |

|

Background Of Change (Conversion) |

Feeling of uncertainty and doubt about the Islamic way of salvation. Small book purchase but did not understand due to Hindu-background Bible languages. After 10 years, he met an evangelist as his customer and bought one Bible from him. In his expression, with the help of the Holy Spirit, he could understand most of the languages and believe in Jesus. Afterward, he began to open one spot of his shop to gather together as a Jamaat even before taking Baptism. |

In class seven, bought a book at a cheap price and learned something about Isa Moshi from the Bible and Qur’an verses. When a house was burnt down, found an Inzil sharif in a suitcase. From that time, the desire to know more has grown. Next year, joined a one-week training course teaching about Isa as the Savior through the Qur’an. Trainers were satisfied with his positive response. After coming back from the training, he and several others were baptized in his home town. |

As a child boy, he joined the house worship and sometimes learned biblical teaching. Not allowed to go to church by mother as a Muslim. He tried to be baptized but was denied and asked to wait because he was a Muslim. Also, after uncovering a false report culture and struggling for several years, came to city and worked with foreigners. Through discipleship with them, confessed sins and felt some changes in his inner being even to outside circumstance |

|

Family & Community Response |

Expelled from family. Persecuted verbally and physically by the Muslim majority in the village. Some Muslims took his goods on purpose or did not pay for their purchases. Thus, he decided to get a Baptism certificate to prove that he was a Christian because the police can protect him and his family from unreasonable persecution. |

Because his father was Imam and he had completed requirements to be an Imam from childhood. He started work in Mosque as a local Imam to preach about Isa for 5 years. Three times social judgment, but no harm because of being self-dependent. Now a free preacher sometimes in Mosque, or in church. |

Because of the good reputation of Christians in his hometown such as caring the poor and working Christian NGO several years, not too much persecution. |

|

The motive of present social Identity |

In order to communicate with the majority of Muslims, he uses Kitabul Mokaddos (Mussolmani Bible) and he also identifies as Isai. |

Isai Muslim, but someone sees him as a Muslim in his local area, but some others also see him as a Christian when preaches the Bible to the other town tribe of Christians |

Was encouraged to be identified as an Isai Muslim following the organization’s heart to reach out to Muslim neighbors. When he goes to the village where the organization works, sometimes introduce himself as a Muslim because of dealing mostly with village Muslims and not falling trouble. |

|

Social Identity |

Christian/Isai |

Isai Muslim/Muslim (mainly) (sometimes considered Christian) |

Christian/Isai and Isai Muslim/Muslim |

References

Ahmed (pseudonym) (2014). Interview by author. Dhaka, Bangladesh. November 27.

Ayub, Edward (2009). “Observation and Reactions to Christians Involved in a New Approach to Mission” St Francis Magazine 5:5 (October):21-40.

Baeq, Daniel Shinjong (2010). “Contextualizing Religious Form and Meaning: A Missiological Interpretation of Naaman’s Petitions (2 Kings 5:15-19)” International Journal of Frontier Missions 27:4 Winter:197–207.

Baig, Sufyan (2013). “The Ummah and Christian Community” in David Greenlee, ed., Longing for Community: Church, UMMAH, or Somewhere in Between? Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 69-78.

Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin (1989). Prolegomena to the Psychological Study of Religion. London: Associated University Press.

Croft, Richard (2014). “Muslim Background Believers in Bangladesh: The Mainline Church Scene with These New ‘Church’ Members from Muslim Backgrounds” St Francis Magazine 10:1 (April):37-59.

Dutch, Bernard (2000). “Should Muslims become ‘Christian’?” International Journal of Frontier Missiology 17:15-24.

Green, Tim (2013a). “Conversion in the Light of Identity Theories,” in David Greenlee, ed., Longing for Community: Church, UMMAH, or Somewhere in Between? Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 41-52.

_____ (2013b). “Identity Choices at the Border Zone,” in David Greenlee, ed., Longing for Community: Church, UMMAH, or Somewhere in Between? Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 53-68.

Hasan (pseudonym) (2014). Interview by author. Bangladesh. December 9.

Hiebert, Paul G. (1994). Anthropological Reflections on Missiological Issues. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House.

_____ (2009). The Gospel in human context: Anthropological explorations for contemporary missions. Grand Rapids, MI: BakerAcademic.

Jennings, Nathaniel Issac (2007). “The Muslim Background Believers Movement in Bangladesh.” Th.M. Thesis. The Queen’s University of Belfast. UK.

Johnson, Carl (pseudonym) (1999). “Training Materials for Muslim-Background Believers in Bangladesh.” D.Miss., A Major Project. Trinity International University. Deerfield, IL.

Lee, Musa (pseudonym) (2014). Interview by author. Dhaka, Bangladesh. May 3.

Lewis, Rebecca (2007). “Promoting movements to Christ within natural communities” International Journal of Frontier Missiology 24:75-76.

Lexico (2020). “Identity,” Lexico (powered by Oxford) website, http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/identity (accessed June 16, 2020).

Meral, Ziya (2006). “Conversion and apostasy: A sociological perspective” Evangelical Mission Quarterly 42 (April):508-513.

Mol, Hans J. (1976). Identity and the Sacred. New York: Free Press.

Moreau, A. Scott (2005). “Contextualization,” in Michael Pocock, Gailyn Van Rheenen, and Douglas McConnell, ed., The changing face of world missions: Engaging contemporary issues and trends. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 321-348.

Parshall, Phil (2003). Muslim evangelism: Contemporary approaches to contextualization. Waynesboro, Georgia: Gabriel Publishing.

Rana (pseudonym) (2014). Interview by author. Dhaka, Bangladesh. November 3.

Taher, Abu (2009). “Society of Bangladesh/ The Obstacles to build up Jamaat (Bangla).” Translated by Md. Golam Rabbani. 1-3. Education Welfare Trust, Gajipur, Bangladesh.

_____ (2014). Interview by author. Dhaka, Bangladesh. October 24.

Travis, John (1998). “The C1 to C6 spectrum” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 34:407–408.

Travis, John, and Woodberry, Dudley (2010). “When God’s kingdom grows like yeast: Frequently-asked questions about Jesus movements within Muslim communities” Mission Frontiers 32 (July-August):24-30.

Whiteman, Darrell (1997). “Contextualization: the theory, the gap, the challenge” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 21:2-7.

Woodberry, J. Dudley (1989). “Contextualization among Muslims: Reusing common pillars,” n Dean S. Gilliland, ed., The Word among us: Contextualizing theology for mission today. Dallas: Word Publishing, 282-312.

Yoder, Michael L, Lee, Michael H., Ro, Jonathan, and Priest, Robert J. (2009). “Understanding Christian Identity in terms of Bounded and Centered Set Theory in the writings of Paul G. Hiebert” Trinity Journal 30NS:177-188.