The Life and Ministry of Erlo Hartwig Stegen

Elfrieda M.-L. Fleischmann and Ignatius W. Ferreira

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, October 2021

Abstract

While the start of the twentieth century was marked by great Protestant mission advances in the Global South, other interest groups such as European colonialists promoted their own sets of ideologies that often impeded missionary work. In an effort to bring the gospel to the Zulu nation in South Africa, Louis Harms envisioned his missionaries bringing the gospel to Africans before they would experience the destructive influence of colonization. About a century later, Erlo Hartwig Stegen, true to Harm’s vision played a fundamental role in bringing the gospel to the Zulu nation. This article provides insight into the missionary role that Erlo Stegen played both during and after the South African Apartheid dispensation, focusing on his missiological context, style, principles, and legacy.

Key Words: Erlo Hartwig Stegen, KwaSizabantu Mission, revival, South Africa, Zulus

Introduction: Historical Roots of Revival and Missions (1708–1902)

In contrast to the European Reformation during the sixteenth century, adherents of Humanism only a century later contended that truth could be obtained only by reasoning and thereby rejected all claims to truth that they considered in opposition to common sense (Paas 2016, 234). Rationalism reached its peak in the seventeenth century and was followed by Romanticism. Europe during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was therefore exposed to a confluence of philosophies that undercut the authority of Scripture.

In sharp contrast to this increasingly autonomous atmosphere of the nineteenth century, a Protestant revival was experienced in Lüneburg Heath, northern Germany in 1840 under Louis Harms (Kim 2011, 252). This revival swept humanistic philosophies aside and realigned Christianity and Christian living with Scripture. Some historians have favorably compared the effect of the Lüneburg revival to the Reformation brought about by Martin Luther three centuries earlier (Jackson 1953, 156-157). The effect of Bible-based preaching in the Lüneburg revival was felt throughout the whole region of lower Saxony in northern Germany. One direct consequence of this revival was a great overflow of missionaries, with many missions being established in countries spread throughout various continents, such as India (1864), Australia (1866), North America (1867), New Zeeland (1875), Persia (1880), Brazil (1898), and later Ethiopia (1927), Indonesia (1974), Egypt (1978) central Africa (1980), and South Africa (Oosthuizen 1985, 13).

As part of his effort to safeguard a commitment to scriptural authority against the onslaught of critical human philosophical influence, Harms envisioned missionaries who would share God’s salvation plan with Africans and protect them against the increasingly autonomous European mind-set of individualism, materialism, and secularization (Fleischmann 2021). With this long-term goal in sight, Harms aimed through his missionaries to educate indigenous African people to read the Bible for themselves before the destructive influence of Europe’s Enlightenment could arrive and capture their attention. As spiritual life and belief in the authority of Scripture was ebbing in Europe, Harms placed a sacred trust in his missionaries to Africa, in the hope that Africans would in turn be instrumental in reviving Europe through the sincere and undiluted preaching of Scripture (Stegen 1983). From Harms’s prayer life emanated the vision to build a ship, the Kandaze, that would take the gospel to Africa (Harms, 1900). The Kandaze brought the forefathers of another great missionary, Erlo Hartwig Stegen, to South Africa. Erlo Stegen would become instrumental in a significant revival among the Zulus, in which God empowered Zulu missionaries to preach God’s word with authority even to Europeans. That revival among the Zulus seems to have been a fulfilment of Harms’s missionary and revival vision of a century before. This article focuses on the role that Stegen played during and after the Apartheid South African dispensation, focusing on his missiological context, style, principles, and legacy.

Erlo Stegen the Person

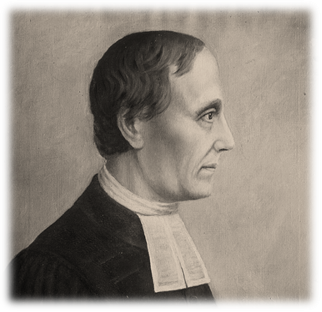

Figure 1: Louis Harms (left) and Erlo Stegen (right)

Stegen’s ministry has been conducted mainly among the Zulu nation, and little academic work has been done on his life, ministry, and teachings. Important to note at this juncture is the fact that there are some remarkable similarities between the ministries of Louis Harms and Stegen, two men who served a century apart from each other. In fact, Stegen’s work was an indirect result of Harms’s missionary endeavors.

Ancestral Roots and Christian Influence

Both Harms (1808–1865) and Stegen (1935–) came from Christian family backgrounds. Harms’s ancestors were Protestant Christians. Stegen’s maternal ancestors, the Witthöfts, arrived on the Kandaze (the ship that Louis Harms had built) in 1871 in Port-Natal (Durban) (Du Toit 1986a, 32; Kitshoff and Basson 1985, 14). Stegen’s paternal grandfather, Heinrich Christoph Stegen (1849–1904), encountered the revival led by Harms and felt a calling to Africa. Heinrich, age 33, and his wife Catharine (1862–1934), age 21, left by ship from Hamburg for South Africa in June 1883. They planned to support Harms’s Hermannsburg Mission Society through agricultural activities (KSB 2016a; Volker 2017, 427).

Early Years and Education

Erlo was the fourth son among six children and was born at Paardefontein, South Africa. He was forced to quit his schooling at an early age due to recurrent headaches, which became his “thorn in the flesh.” Unable to attend school, Stegen instead used his spare time to study Scripture, memorizing large portions thereof as he was confined to the farm. During these isolated years he developed a deep love for Scripture and often meditated over its contents (Fleischmann 2021).

Conversion

Erlo Stegen’s conversion was intense. Through the inspired preaching of Anton Engelbrecht at Lilienthal, he became increasingly aware of the evilness of his own heart and his tendency to lie and fight—even after taking Communion. He realized his need for the working of the triune God in his life. Although at the age of about 13 he had a desire to live a life that was pleasing to God, Erlo found his nature revealing the opposite; the conflict drove him to turn to Christ as his Savior. Scripture passages impacting his conversion were James 1:22–24, James 2:10, Matthew 5:21–22, and Ezekiel 18:4 (Fleischmann 2021).

Calling

Stegen received his calling soon after his conversion. However, being confronted by the prospect of a poor life in economic terms, he disregarded it. Young Erlo cherished three activities: farming, making money, and sports, the last of which he hoped would be his destiny. For 18 months during 1950 and 1951 Erlo went through inner torment, which he later described as like a foretaste of hell (Stegen 1988). To put his mind on something else, he took part in various activities and worked hard at them. He excelled in tennis, even qualifying for the national South African under-16 team (Du Toit 1987, 20). However, even though he accomplished this particular dream, Stegen remained utterly unhappy and restless until he accepted God’s calling on his life.

The Ministry of Erlo Stegen

Whereas Louis Harms was a preacher doing mission work, Stegen was a missionary who also became a preacher after he established the KwaSizabantu Mission in the heartland of what is now South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province in 1970. Since then, the mission has grown into one of the largest Protestant missions in the Southern Hemisphere. It is a hub for mission activities, with semi-annual youth conferences that draw between four and six thousand youth for seven days of services. Various national and international outreaches are also conducted from this mission. As a pioneer of experimental farming activities, Stegen equipped the mission to sustain itself economically (Fleischmann 2021).

Revival

Under Harms’s preaching revival came to Hermannsburg in 1848 (Kim 2011, 252). Prussians, Saxons, and Hessians would come from the surrounding villages, sometimes walking 80 kilometers to hear sermons over the weekend (Harms 1900, 49). The church building was soon too small. As a solution to this problem, Harms conducted three services every Sunday (Stegen 2013, 5). His once-a-year mission festivals drew crowds of up to 6,000.

Revival came to Stegen and his little Zulu congregation at Maphumulo in 1966 after months of studying the book of Acts and honest introspection. Confronted by God’s Word, as they measured themselves against the first church in Acts, they cried out to God for his mercy and sought to mend their ways where they had lived unscripturally, dishonoring him (Visser 2014). As they sought Him with all their hearts, they suddenly became aware of his presence (KSB 2007). They experienced a “rushing of the wind” and knew that God had answered their prayers.

Directly after this experience, the first person who came to Erlo Stegen for help was the head of a school for witches (Khwela and Dube 2019). Thoroughly convicted she confessed her sin, Stegen prayed for her, and she was delivered. The Holy Spirit convicted individuals of sin, righteousness, and judgment starting with the strongholds of evil. Day and night, people arrived uninvited to seek Stegen’s assistance (Khwela and Dube 2019). They all had a strong desire to find peace with God.

Becoming a Popular Preacher

As with Harms, large crowds would congregate to hear Stegen preach in Zulu. Speaking with a strong sense of God’s authority, he quickly became a popular preacher. His fearless and honest preaching awakened the people to their lost and miserable state. Some loved him for it, while others hated him for refusing to compromise with their sin. Whereas Harms’s sermons have been printed and published in text, hundreds of Erlo Stegen’s audio sermons can be found on various digital platforms (for example, Sermon Index2021; KwaSizabantu Mission 2021). Ministers’ conferences at KwaSizabantu Mission have typically drawn nearly 2,000 ministers and preachers of the gospel; semi-annual seven-day youth conferences have attracted 4,000 to 7,000 youths at the Mission’s expense (Fleischmann 2021). An estimated three million people have visited KwaSizabantu Mission over the past half century free of charge (Fleischmann, Ferreira and Muller 2021a).

Opposition

The construction of Harms’s mission ship, the Kandaze, encountered opposition from friends and brethren who hinted that he was out of his mind (Greenwald 1867, 18; Stevenson 1862, 333). Although he received warning letters, Harms carried on with the work (Harms 1900, 80). Convinced that the ship was God’s will, he sought God for the funds. God in return provided the needed finances in various ways, and “the vessel was built by faith and laden with prayer” (Harms 1900, 81).

Two themes have appeared prominently in Stegen’s ministry: rivers of life and opposition (Fleischmann, Ferreira, and Muller 2021b). From the very start of the revival, many turned from their sin to Christ and received new life. Others fell away along the road and became bitter enemies of the work (Fleischmann, Ferreira, and Muller 2021b). One of his leading admirers, the Zulu Prince Buthelezi, remarked that “despite extraordinary burdens wrought through spiritual battle, Stegen has flourished and his life’s work at KwaSizabantu has flourished with him” (Buthelezi 2015, 1-2). Similarly, Hammond stated that Stegen’s mission “has thrived in spite of times of great opposition and slanderous campaigns against it (Hammond 2006, 4). Stegen experienced waves of attacks from various angles on him personally and on his mission work” (Fleischmann, Ferreira, and Muller 2021a). Since he was meeting with Zulu brethren during the zenith of Apartheid, Stegen was frequently interrogated by the South African police, who suspected him of being a communist (Khwela and Dube 2019). His ability to hold assemblies was strictly curtailed because, according to the Native Administration Act of 1927, meetings of more than ten persons in native areas were allowed only by permission of the Native Commissioner or Resident Magistrate (Landis 1957, 46).

The Missiological Impact of Stegen’s Ministry

The impact of Stegen’s ministry can be witnessed in the lives of many. First, from the inception of the associated Zulu revival, the gospel has radically changed the lives of the worst of sinners, as further described below. Second, during the 1980s Kurt Koch conducted extensive research on these cases and published a book, God amongst the Zulus, in German and in English (Koch 2011). Third, Stegen has gone on extensive missionary trips and been invited to speak at outreach events on every continent (Fleischmann 2021). Fourth, with the coming of the digital age, his sermons have been indexed on numerous digital platforms and have been downloaded worldwide (Sermon Index 2021). Fifth, the annual KwaSizabantu ministers’ conferences have brought together a network of preachers, ministers, and Christian workers from all denominations and have provided a platform for dialogue and discussion (Fleischmann 2021).

Stegen’s missiological context was an Apartheid and post-Apartheid South Africa. At the zenith of the Apartheid system, he worked among the Zulu nation within KwaZulu Natal province. Stegen therefore had to face much opposition, not only from the Apartheid government of that time but also from many white South Africans. Due to the lack of educational opportunities for the Zulu nation, Erlo Stegen followed the school of Old Testament prophets as well as Jesus in the New Testament, namely training people through personal mentoring rather than classroom study. He equipped his Zulu co-workers for over five decades through the integration of work and learning, enabling them to become capable missionaries who spread the gospel through a scriptural life and revival power (Fleischmann 2021). In turn, these Zulu co-workers are now training a younger generation of missionaries. As the Zulus grew in spiritual depth, the mission work expanded.

Stegen led the mission work with a firm conviction that God would provide. Although Stegen did not open a theological seminary, he and his wife, Kay, established a teacher training college for missionaries, today called Cedar International Academy NPC. Trusting God to sustain the mission work, Stegen never requested donations or took collections from people but brought his needs to God in prayer (Fleischmann 2021). Stegen has continued until today to make his mission and its branches multi-racial and self-sustainable through experimental farming (Joosten 2019). KwaSizabantu Mission has grown to become one of the largest mission stations in the Global South. In addition, African missionaries have been equipped to take the gospel back to Europe in a powerful manner.

The Legacy of Erlo Hartwig Stegen

Stegen has created a missiological legacy with wide-ranging influence in evangelical circles. His stance that mission stations should be self-supportive has borne fruit. Today the KwaSizabantu Mission has developed into a self-sustainable mission station (Fleischmann 2021). Yet to Stegen, God’s call to obedience remains more important than anything else. Stegen holds the view that if there is no unconfessed sin between him and God, he is usable in God’s hands to accomplish His purposes (Fleischmann, Ferreira, and Muller 2021b; Visser 2014). Stegen therefore views his top priority as caring for his relationship with God (Fleischmann 2021).

Mission, Not Apartheid

Experiences on multiple dimensions provided Stegen with a conceptual lens to make sense of the pain caused by the racial hierarchies of the Apartheid regime. Having grown up under a mixture of South African Apartheid and entrenched, nationalistic German culture, Stegen first had to come to grips with the issue of racism and nationalism in his own life (Fleischmann 2021).

Confronted by the Holy Spirit and having accepted God’s call to service among the Zulus, Stegen experienced God’s resurrection power in his life to overcome his own pride and nationalistic tendencies, and it became his constant prayer to see the world as God sees it. Stegen’s example of serving the Africans (Khwela and Khwela 2019) as a missionary affected other farmers as well, to the extent that they, too, during the height of Apartheid allowed Africans to sit in the front seat with them as they traveled, even though they were despised by some other farmers for doing so (Duvel 2019). When Mrs. Mzila, one of his congregants, lacked food, Stegen ordered seeds, hoed her garden, and planted vegetables, showing her how to sustain herself and her family practically (Duvel 2019). His way of living and serving his Zulu neighbors within a time of racial hatred made a deep impression among the Zulu nation (Dube 2019). In Stegen’s attitudes toward interracial relationships, he was half a century ahead of his time, breaking new ground and preparing the way for others to follow.

Under Apartheid (which cut through both laws and culture), whites did not mix with other races. The year 1950, during which the Group Areas Act—setting up the basis for the construction of an apartheid society—was passed (Kaplan et al. 1971, 86), was also the time of Erlo’s conversion, which in hindsight laid the foundation for the construction of a multi-cultural society, even in the midst of Apartheid. As South Africa became increasingly polarized along racial lines, God destined Stegen to bridge the widening racial gulf through sacrificial living and service to his fellow human beings (Fleischmann, Ferreira, and Muller 2021b).

During the Apartheid years, the law forbade establishment of a mission outpost within three miles from another one (Van Rooy 1987, 12). This law restricted Stegen from preaching in the more densely populated Umvoti River area, since another missionary or church was already there (Du Toit 1987, 29). In 1957, a new regulation issued by the Minister of the Interior prescribed further restrictions. Through the earlier Communal Reserves Act of 1909, any religious organization other than the established church was required to obtain special permission to hold any service to be attended by more than five members (Kaplan et al. 1971, 303).

Stegen’s only option was to pitch his evangelization tent at Kings Cliff, south of the Umvoti Valley on his brother Friedel’s shop grounds, where he would preach daily for the next 14 months (Fleischmann 2021). Later he moved his tent to Maphumulo, north of the river and onto another one of Friedel’s shop grounds.

As noted earlier, white missionaries living among the Zulu nation and supporting them, such as Stegen was doing, were viewed with suspicion by the Apartheid government. As no mainline church was financing Stegen’s ministry, he used his farming skills and experimented with various projects to provide the necessary means of support to the Zulu people (Joosten 2019). At the same time, the Holy Spirit abolished separatist attitudes and racism lurking within the hearts of his congregation (Ngubane 2018). Stegen’s converts became one sanctified body in Christ.

Mission as Living a Counterculture Informed by the Word of God

Stegen’s preaching has emphasized living a scriptural and holy life, pleasing to God (Visser 2014). Living a simple life informed by the Word of God has enabled Stegen to break through the layers of Zulu pride (Fleischmann 2021). Living in their midst as they lived, even through the trying Apartheid years, touched the Africans deeply. KwaSizabantu Mission was established in 1970 as a multi-cultural mission with no racial apartheid (Fleischmann 2021). Even during these early years, all races shared their meals together in the dining hall.

Conclusion

It could be said that the vision of Louis Harms, to send missionaries to Africa to safeguard the gospel against the onslaught of the Enlightenment in Europe, has been realized in the ministry of Erlo Stegen. In both ministries, mission was the fruit of revival. Through the revival that occurred among the Zulus, God equipped missionaries to bring the message of revival to Europe.

More than 18,500 youth dealing with drug addiction have passed through the spiritual restoration program at KwaSizabantu Mission over the past seven years. Their testimonies of God’s transforming power in their lives have reached over 5,500 schools across South Africa during this time. As mission work is God’s business, God has provided the Global South with missionaries able to reach out to the Global North. In his sovereignty, he can use any sanctified vessel to impact the world through revival.

References

Buthelezi, Mangosutho (2015). “In Celebration of the 80th Birthday of the Reverend Erlo Stegen” Inkatha Freedom Party website, https://www.ifp.org.za/in-celebration-of-the-80th-birthday-of-the-reverend-erlo-stegen/ (accessed 15 September 2021).

Dube, Lidia (2019). Erlo Stegen/ Interviewer: E. M.-L. Fleischmann. Fleischmann Private Collection.

Du Toit, Welly (1987). God se Genade, die verhaal van Kwa Sizabantu (God’s Grace, the Story of Kwa Sizabantu). Pretoria: Publication Scan.

Duvel, Carl H. (2019). Erlo Stegen/Interviewer: E. M.-L. Fleischmann. Fleischmann Private Collection.

Fleischmann, Elfrieda M. (2021). “Erlo Hartwig Stegen: A missiology evaluation of his life, ministry and teachings.” Unpublished PhD dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom.

Fleischmann, Elfrieda, Ferreira, Ignatius W., and Muller, Francois (2021a). “A two-tier protestant evaluative framework for cults applied to KwaSizabantu Mission” In die Skriflig 55(1): 1-9. Available online at https://indieskriflig.org.za/index.php/skriflig/article/view/2686 (accessed 20 September 2021).

_____ (2021b). “Protestant Revivals (Awakenings) and Transformational Impact: A comparative evaluation framework applied on the revival among the Zulus (South Africa)” Transformation: An international journal of holistic mission studies Available online at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/02653788211027269 (assessed 20 September 2021).

Greenwald, Emanuel (1867). Foreign Mission Work of Pastor Louis Harms and the Church at Hermansburg. Philadelphia: Lutheran Board of Publication.

Hammond, Peter (2006). “40 Years of Revival at KwaSizabantu” Christian Action website, https://www.christianaction.org.za/index.php/articles/revival/292-40-years-of-revival-at-kwasizabantu (accessed 13 October 2021).

Harms, Theodor (1900). Life Work of Pastor Louis Harms. Trans. By M. E. Ireland. Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society.

Jackson, Samuel M. (1953). New Schaff-herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (Vol. 5). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Joosten, Dietmar (2019). Erlo Stegen/ Interviewer: E. M.-L. Fleischmann. Fleischmann Private Collection.

Kaplan, Irwing., McLaughlin, James L., Marvin, Barbara J., Nelson, Harold D., Rowland, Ernestine E., and Whitaker, Donald P. (1971). Area Handbook for the Republic of South Africa. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Khwela, Emanuel, and Dube, Jabulani (2019). Erlo Stegen/ Interviewer: E. M.-L. Fleischmann. Fleischmann Private Collection.

Khwela, Emanuel, and Khwela, Grema (2019). Erlo Stegen/ Interviewer: E. M.-L. Fleischmann. Fleischmann Private Collection.

Kim, Huyan J. (2011). “Protestant communities as mission communities.” Unpublished PhD dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom.

Koch, Kurt E. (2011). God among the Zulus. Cape Town: Christian Liberty Books.

KSB (2007). When God Came Down. Kranskop: KwaSizabantu Mission. DVD.

KwaSizabantu Mission (2021). KwaSizabantu Mission website, https://www.ksb.org.za/ (accessed 13 October 2021).

Landis, Elizabeth S. (1957). “Apartheid Legislation” Africa Today, 45-48.

Ngubane, P.M. (2018). Erlo Stegen/ Interviewer: E. M.-L. Fleischmann. Fleischmann Private Collection.

Oosthuizen, Gert J. (1985). Kwa Sizabantu-sending, 'n ondersoek na sy ontstaan en funksionering (KwaSizabantu Mission, an Investigation of its Establishment and Function). University of Pretoria.

Paas, Steven (2016). Christianity in Euroafrica. Wellington: Christian Literature Fund.

Sermon Index (2021). “Erlo Stegen (1935-Present).” Available online at https://www.sermonindex.net/modules/mydownloads/viewcat.php?cid=256 (accessed 20 September 2021)

Stegen, Erlo H. (1983). “Die wese van herlewing” (“The Nature of Revival”). Unpublished, transcribed.

_____ 1988. “Revival Number One.” Unpublished, transcribed.

_____ 2013. Herlewing begin by jouself (Revival Starts with Yourself). 2nd ed. Kranskop: KwaSizabantu Mission Publishers.

Stevenson, William F. (1862). Some account of what men can do when in earnest. New York: Robert Carter & Brothers.

Van Rooy, Jacobus A. (1987). Kwa Sizabantu, dieptestudy van 'n herlewing (KwaSizabantu, an In-depth Study of a Revival). Vereeniging: Reformatoriese uitgewers b.k.

Visser, Theo (2014). Revival and Conviction of Sin. Cape Town: Christian Liberty Books.