An Enkiteng Hermeneutic—

Reading (and Hearing!) the Bible with Maasai Christians:

A Review Essay and Proposal

Joshua Robert Barron

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, October 2021

Abstract

God’s communication of his Word to people has always been culturally specific. Rather than falling prey to a feared cultural relativizing of the Christian gospel, the cultural contingency or particularity of divine-human communication entails the importance of contextual realities within different cultures, often represented by their languages. Human contexts should therefore be taken seriously by biblical hermeneutics. Moreover, care must be taken not to denigrate any cultural context due to its alleged inferiority to another, as has happened all too frequently in modern interactions between Europeans and Africans.

The “Maasai and the Bible” project, sponsored by VID International University in Norway in cooperation with Tumaini University Makumira in Tanzania, has taken the specifically Maasai human context seriously in an examination of biblical hermeneutics. The project has resulted in four recent publications studying Maasai reception and hermeneutics of biblical texts. This article introduces that project, reviews its four books, then proposes an enkiteng (cow) hermeneutic as an appropriate approach to Scripture in Maasai contexts.

Key Words: African hermeneutics, intercultural hermeneutics, Maasai Christianity

Introduction

We all read, or listen to, Scripture through a hermeneutical lens. All such lenses are necessarily tinged by culture. No reading, or hearing, of Scripture is acultural (Ukpong 1995, 6). All human understandings of Scripture, like all Christian theologies, are culturally contingent. This should not surprise us because Scripture itself is not acultural. Rather it is itself contingent on the particularity of its languages and, therefore, of those languages’ cultures. This is true of the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts as well as every translation ever produced. All divine-human communication is necessarily specific to a given culture. Because this cultural contingency is inherent in all human understanding, “none of us has a neutral perspective on … the Bible” (Mburu 2019, 22). Acknowledging this reality does not relativize the message of the gospel. Instead, the cultural contingency of human understandings of the Bible entails that the contextual realities within different cultures—often represented by their languages—matter. It is therefore not appropriate to demand, for instance, that an African adopt a European culture in order to follow Christ. By extension, then, biblical hermeneutics must not neglect human cultures but engage them.

Some practitioners of historical-critical methods of biblical interpretation are convinced that they are just reading scripture with all culture cut away. They are, of course, gravely mistaken and confused by their own cultural myopia. A healthy hermeneutic will not only attempt to explain, insofar as this is possible, what the text meant to the original recipients (whether as readers or as listeners) in their particular cultural contexts but will also deliberately engage with the cultures of contemporary recipients.

Just as “a Theologia Africana which will seek to interpret Christ to the African in such a way that he feels at home in the new faith” (Sawyerr 1971, 240) is necessary for a healthy African Church, so do healthy African hermeneutics require “African biblical scholars [who are] wary of running away from their African selves or identities and relying heavily on Western paradigms” (Masenya and Ramantswana 2015, 2). Moreover, “Interpreting the biblical text is never, in African biblical hermeneutics, an end in itself. Biblical interpretation is always about changing the African context. This is what links ordinary African biblical interpretation and African biblical scholarship, a common commitment to interpret for contextual transformation” (West 2018, 248).

In the specific context of the Maasai people of East Africa, “While there are certainly areas where Maasai culture can benefit from Christian transformation, a recovery of traditional Maasai cultural values through a theologically robust process of inculturation can strengthen the Maasai churches as well” (Barron 2019, 17). This process will necessarily require a contextual African (Maasai) hermeneutic. The Maasai and the Bible project (directed by Professor Knut Holter at VID Specialized University in Stavanger, Norway), researching the responses of the Maasai of Tanzania and Kenya to the Bible, has resulted in four recent publications. This article introduces the “ordinary reader (African) hermeneutics” used by the researchers of that project and by myself, introduces the Maasai and the Bible project and briefly review its publications, and propose a hermeneutical model for Maasai hermeneuts. Note that I have more fully reviewed those volumes elsewhere (Barron 2021c); some of my observations there will necessarily overlap with what follows. Note as well that the three Peter Lang volumes are academic monographs, whereas the Acton volume is more accessible.

Intercultural Hermeneutics, African Hermeneutics, and the Intersection between the Academy and Ordinary Reader

Academically trained “professional” readers and untrained “ordinary” readers often approach biblical texts from strikingly different perspectives. Both groups have something to offer the Church, however, and neither should scorn what the other brings to the table. Biblical scholars such as Justin S. Ukpong of Nigeria and Gerald O. West of South Africa have emphasized, specifically within African contexts, the value that ordinary readers bring to biblical interpretation and the ways in which ordinary readers and trained scholars each have something to offer the other. Within the maturing field of African biblical studies or African hermeneutics, interpreters deliberately address African contextual realities. Because no one approaches biblical texts from a neutral cultural perspective (even if some people might think, in their monocultural myopia, that they achieve this feat), it is just as important to be aware of the cultural and linguistic contexts of readers (and listeners) as it is of the various contexts of the original audiences of the biblical texts. Intercultural hermeneutics recognizes both that no readings of Scripture are free from cultural bias and that the cultural context of the readers actually enable understanding. In addition, intercultural hermeneutics admits that any given biblical interpretation may be more or less valid (Elness-Hanson 2017, 16–17 and 40) as well as that the biblical texts are inherently “plurivalent” (Nkesela 2020, 11). While many recent studies make use of intercultural hermeneutics to privilege the voices of “ordinary African readers” in Bantu contexts (e.g., see Kĩnyua 2011), heretofore there have been few examinations of Nilotic cultural contexts.

In many parts of the world, engaging with the culture necessarily entails engaging with the orality of the culture. As an overly literate exegete, it is all too easy for me to neglect the importance of the intended aurality of the Scripture: these texts were written not just to be read, but to be listened to. While Augustine of Hippo may have been inspired by the singsong chant of tolle lege (“take and read”), Paul does not teach us that faith comes by reading but rather that “faith comes by hearing” (2 Cor 5:17). Deuteronomy claims to be “the words that Moses spoke” to the Israelites and to which they listened (Deut 1:1). When Hilkiah found the lost book of the Torah, the people did not gather around to read it silently. Rather, Shaphan read it to Josiah, and then the king read it to all the people (2 Ki 22:3–23:2). While it is commendable to devote oneself to read and study the Word of God like Ezra (Ezra 7:10), even so that Word is meant to be heard. It is clear that “the ancient societies of the Bible were overwhelmingly oral. People originally experienced the traditions now in the Bible as oral performances” (Rhoads 2009, ii). Likewise, orality and aurality remain essential to many African societies today. Many African Christians—including among groups like the Maasai—primarily experience the Word of God as a spoken Word. It is therefore necessary for biblical interpretation in Maasai contexts to consider biblical texts as they are heard, not only how they appear in literate form.

Maasai and the Bible Project

Knut Holter of VID Specialized University in Norway recently oversaw a several-year project entitled “Potentials and problems of popular inculturation hermeneutics in Maasai biblical interpretation,” informally abbreviated as the “Maasai and the Bible” project. The Maasai are a Nilotic people living in Kenya and Tanzania. This Maasai and the Bible project was carried out in the context of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania (ELCT) and in collaboration with Tumaini University Makumira. A Maa language translation of the Bible has been available at least in part for 50 years. The Bible is by far the most widely available Maa language text and can truly be said to be “a Maasai book.” It is daily read, or listened to, by Maasai Christians striving to live their faith within Maasai contextual realities. The Maasai and the Bible project sought to explore the hermeneutics of Maasai “ordinary readers.”

When I informed missiologist Doug Priest, Jr.—former missionary among the Maasai of both Kenya and Tanzania and author of Doing Theology with the Maasai (Priest 1990)—about the books resulting from this project, he observed to me that “contextualization and indigenous theology have come a long ways since my time.” They have indeed! Peter Lang’s “Bible and Theology in Africa” series, edited by Knut Holter, has been a blessing toward this end, providing examples of this contextualization and indigenous Christian theology for the benefit of World Christianity. The description of this series reminds us that

The twentieth century made sub-Saharan Africa a Christian continent. This formidable church growth is reflected in a wide range of attempts at contextualizing Christian theology and biblical interpretation in Africa. At a grassroots level ordinary Christians express their faith and read the Bible in ways reflecting their daily situation; at an academic level, theologians and biblical scholars relate the historical traditions and sources of Christianity to the socio- and religio-cultural context of Africa. In response to this, the Bible and Theology in Africa series aims at making African theology and biblical interpretation its subject as well as object, as the concerns of African theologians and biblical interpreters will be voiced and critically analyzed (Peter Lang 2021).

The Maasai and the Bible Project has provided, in addition to a handful of academic articles, three monographs to this Peter Lang series and an edited collection of research essays published in Nairobi:

Elness-Hanson, Beth E. (2017). Generational Curses in the Pentateuch: An American and Maasai Intercultural Analysis. Bible and Theology in Africa 24. Edited by Knut Holter. New York: Peter Lang, 291 pp., ISBN 9781433141218. Hardback. US$97.60.

Lyimo-Mbowe, Hoyce Jacob (2020). Maasai Women and the Old Testament: Towards an Emancipatory Reading. Bible and Theology in Africa 29. Edited by Knut Holter. New York: Peter Lang, 225 pp., ISBN 9781433173493. Hardback. US$99.95.

Nkesela, Zephania Shila (2020). A Maasai Encounter with the Bible: Nomadic Lifestyle as a Hermeneutic Question. Bible and Theology in Africa 30. Edited by Knut Holter. New York: Peter Lang, 227 pp., ISBN 9781433173684. Hardback. US$99.95.

Holter, Knut and Justo, Lemburis, eds. (2021). Maasai Encounters with the Bible. Nairobi: Acton Publishing, 180 pp., ISBN 9789966888934. Paperback. Kenyan Shillings 1900.00 (between US$18.00–19.00).

As my professional life for the past 14 years has revolved around the realities of Maasai Christianity, and since I speak the Maa language, I learned of this project with great anticipatory excitement.

Content Summaries of the “Maasai and the Bible” Publications

Generational Curses in the Pentateuch:

An American and Maasai Intercultural Analysis

The first monograph published as a fruit of the Maasai and the Bible project was Elness-Hanson’s Generational Curses in the Pentateuch. Given the cultural importance of the curse (oldeket) in Maasai culture, I was especially pleased when this volume was released. Whereas “American, Enlightenment-influenced has frequently demythologized the concept of the curse” (8), as well as other spiritual realities, for the Maasai (and other African groups), the efficacy of both curses and blessings is assumed as a matter of course: “the results are real” (95). While Maasai consider blessings to be “the way of life,” frequently “the fear of curses” is what “drives and controls behavior” (91–92). Thus typical Western hermeneutics often fail to have answers for the questions which Maasai Christians, in common with many Christians across Africa, are asking. Elness-Hanson attempts to come alongside Maasai readers, recognizing her own outsider status, with an intercultural hermeneutic (15) that takes seriously the African (and specifically Maasai) questions being asked of the biblical texts.

After discussing the importance of intercultural analysis within World Christianity in order to “purposefully nurture agency for the voices of those on the margin” (3), Elness-Hanson outlines the contexts from which she researches and writes, and she introduces key terminology. She then begins her research by asking, “How does the traditional Maasai worldview shape the Maasai theologians’ interpretative lens when viewing Pentateuchal generational curses?” to come to “a fuller understanding” the biblical texts in question for both the Maasai as well as for the rest of us (57). Diving deeply into Maasai cultural contexts, she notes the importance of reconciliation as foundation to Maasai understanding of curses and provides a dialogical exegesis of four primary OT texts. Anyone interested in doing the hard work of intercultural hermeneutics, especially in African contexts, should read this book. Elness-Hanson concludes by emphasizing the value of intercultural biblical hermeneutics in “building brides of understanding across cultures,” especially in the context of “the rise of World Christianity” (248).

Maasai Women and the Old Testament:

Towards an Emancipatory

Reading

A biblical scholar from Tanzania, Hoyce Jacob Lyimo-Mbowe helpfully approaches her work from an African cultural perspective. Informed by the work of African women scholars such as Mercy Amba Oduyoye, and especially by Madiapoane Masenya’s bosadi hermeneutic (e.g. Masenya 2004), Lyimo-Mbowe inquires whether biblical texts are oppressive or liberative and emancipatory for Maasai women. (Bosadi means “womanhood” in Northern Sotho.) A traditional Maasai man stereotypically treats the Maasai woman (enkitok) as inferior to the man, counting her as a mere child rather than as an adult (e.g., see Barron 2019). As most Maasai churches are overwhelmingly female (see Hodgson 2005), it is important that the voices of Maasai Christian women (inkituaak) are not silenced. Lyimo-Mbowe’s proposed enkitok biblical hermeneutic lays a foundation with the social action philosophy of “see, judge, and act” (80) that has a goal of bringing a Jesus-centered social transformation. Her discussion reminds me favorably of Andrew Walls’s discussions on the nature of Christian conversion (Walls 1990, 2004, 2012; for conversion in Maasai contexts see Barron 2021a). Lyimo-Mbowe then adds two important Maasai values: unity and solidarity (83). The result is “a participatory approach that brings together the oppressed [i.e., Maasai women] and oppressors [i.e., Maasai men] to discuss their challenges from the biblical point of view and find solutions together” (85). After reviewing the understandings of Maasai “ordinary readers” of four OT passages, including one story that deals with a polygynous family that resonates with Maasai contextual realities, Lyimo-Mbowe concludes with a recognition of the transformative role of the Christian faith, emphasizing that “the Church as a voice for the voiceless should intensify efforts towards the emancipation of women” (212). I believe that her enkitok approach to biblical hermeneutics may provide an opportunity for an “Ephesians Moment” (Walls 2002, 2007) of reconciliation between Maasai men and women (see also Barron 2019).

A

Maasai Encounter with the Bible:

Nomadic Lifestyle as a

Hermeneutic Question

Zephania Shila Nkesela, another Tanzanian biblical scholar, considers the very culture and lifestyle of the Maasai as a hermeneutical question. Within the worldview of traditional Maasai culture, there is no such thing as private ownership of land (enkop). Instead, temporary occupiers of land hold it in trust from God (enkAi) Godself, the creator and true owner of the land (121). (The Maa name for God is ɛnkÁí. The predominate dialect of Maa in Tanzania pronounces this as ɛŋÁí or ŋÁí, which these three Peter Lang monographs anglicize as “Ngai.” For more on Maasai naming of God, see Barron 2021b.) Politically, Tanzania’s forced Vijiji vya Ujamma or villagization policy under President Nyerere (1979–1977) constrained the semi-nomadic Maasai to live in settled villages. Moreover, Kenya’s earlier policy limited Maasai herdsman to designated “group ranches,” and Kenya’s current policy forces privatization of land resources. Even so, many Maasai men continue to travel with their flocks and herds seeking adequate grass and water for their livestock. These contextual worldview and political realities unavoidably impact Maasai understandings of Scripture.

Nkesela wryly notes that “Christianity does not demand changing all aspects of the indigenous people’s culture.” He proceeds to observe that insisting that converts to Christianity must abandon their cultures “might not be a good strategy for Africans like the Maasai” who place such a strong value on their ethno-cultural identity (41). As Kwame Bediako noted nearly 30 years ago, “A clear definition of African Christian identity” is impossible apart from an integration into “an adequate sense of African selfhood” (Bediako 1992, 10). Thus Nkesela acknowledges the cultural “oral text” from which Maasai will necessarily approach the biblical text (37–38). Building on Knut Holter’s “complementary model” of contextualized OT studies (e.g., Holter 2006; see also Holter 2000 and 2008), trained biblical scholars such as Nkesela (and myself) are able to partner with Maasai “ordinary readers” who “acknowledge each other as equal participants despite the different contributions” which each group offers (113). This Maasai contextualized biblical study can address “traditional [and] modern African experience and concerns” (12) while providing “mutual enrichment” (194) for ordinary readers and scholars alike.

Maasai Encounters with the Bible

Knut Holter, a Norwegian theologian with a long history researching African biblical scholarship, and Lemburis Justo, a Maasai theologian, have edited this important collection of essays arising from The Maasai and the Bible Project. In the Foreword, Kenyan theologian Jesse N. K. Mugambi notes that this book contributes to “the necessity and importance of counter-balancing biblical hermeneutics with biblical exegesis” (9). Listed below as subtitles are the nine chapter’s authors and titles of Maasai Encounters listed in the table of contents; some chapters are given longer titles in the text itself.

1. Knut Holter, “Content of a Contextual Project”

Stressing that “the Bible is a Maasai book!” (13), Holter outlines the volume goals, offers “some reflections and perspectives on the encounter between Maasai and the Bible” (13–14), notes “the changing cultural contexts of Christianity” (14–18), provides a brief ethnographic introduction to the Maasai, and briefly summarizes each of the following chapters.

2. Hoyce Jacob Lyimo-Mbowe, “Genesis 1:27 in Maasai Context”

The chapter’s longer title is “Reading Genesis 1:27 with Maasai Research Participants.” After distinguishing between “ordinary readers” and “professional readers,” Lyimo-Mbowe offers a distillation of the pertinent parts of her monograph reviewed above.

3. Zephania Shila Nkesela, “Genesis 13:8–9”

The full title is “Abraham’s Solution to the Land Crisis in Genesis 13:8–9.” Noting that the instinctive Maasai interpretation of this pericope is “If this worked for Abraham and Lot why not for us?” in contemporary land crises, Nkesela’s essay gives glimpses into his PhD research project; his dissertation was later revised as the monograph reviewed above.

4. Suzana Sitayo, “Women, Land, & Bible in Context”

The full title of this essay is “Women, Land, and Bible: Reflections on Mbowe’s and Nkesela’s Essays.” As a Maasai, a woman, and a trained theologian with a pastoral calling in the ELCT, Sitayo’s reflective response is most welcome. Sitayo acknowledges that within Maasai Christianity, “The traditional worldviews continue to dominate people who attend church services, and they also tend to shape the Christians’ view of the Bible.… [T]he church cannot any longer ignore the role of traditional practices and worldviews, simply because it shapes the way people read, understand, and interpret the Bible” (62). She then observes that many “popular” readings (which I would call misreadings) of the Bible actually “cement an oppression of women that is culturally based” (64). Sitayo then asserts that intercultural hermeneutics can serve to emphasize that the proper message of the Scripture offers emancipation and liberation for Maasai women (65). My own research among Kenyan Maasai confirms Sitayo‘s claim (Barron 2019).

5. Gerrie Snyman, “Coloniality, Christianity & Identity”

Snyman’s essay, more fully entitled “Is There a ‘Post’ in ‘Colony’? Reader Reception and a De-Colonial Framework,” sets the book’s essays within the broader context of African hermeneutics and biblical studies generally, noting the legitimate concern for decolonization.

6. Lemburis Justo, “Maasai Context in Relation to the Bible”

Lemburis Justo, co-editor of this book along with Knut Holter, is the second Maasai contributor. On a personal note, I must report that I had only just become acquainted with Justo in December 2020 and was looking forward to getting to know him and to collaborate with him when I learned of his untimely death from illness at the beginning of this year (2021). The full weight of his loss will be felt not only by his family but also by the Maasai Christian community.

The full title of his essay is “Maasai Context in Relation to the Bible: Experiences from Theological Education by Extension.” In Tanzania the Theological Education by Extension (TEE) program, which is widely used across Africa, began operating in 1974 as “a joint venture between the Arusha Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania (ELCT) and the [Roman] Catholic Archdiocese of Arusha” (91). As such, the program has extensive experience “of Maasai contextuality in relation from the Bible” (91). Because TEE is designed to arise from and take place within local contexts (92), it provides an opportunity for “the community involvement” which “enriches and complements the work of theological and biblical scholars” (93).

Justo laments that too often there has been a rift between any theologizing by Maasai ordinary readers and that done by academically trained church leaders. With great frequency, African “professional interpreters” have disregarded “their own cultural contexts as incompatible” with proper scholarly exegesis. In that context, he reminds such professional readers that, though “our exegetical methods detach and distance us from our own culture by offering scientific techniques, the cultural reality of the exegete cannot be excluded from the process of scriptural interpretation” (95). Justo’s point is that, instead of rejecting their Africanity as foreign to Christianity, African exegetes should bring the perspectives which arise from their very Africanity into the exegetical process. When an African disregards or discards his or her culture in favor of the “objective” methods of Western scholarship, the typical result is merely an imposition of Western cultural paradigms “on African interpretive communities” (95), bringing about the need for the hermeneutical decolonization which Snyman discusses in the previous chapter.

Engaging with Kenyan theologian John S. Mbiti (1979), Justo emphasizes that Christian conversion takes place within cultures rather than throwing out culture (96–97). As Andrew F. Walls states in many places, Christian conversion is the turning toward Christ “what is already there.” Justo then gives an example of this understanding of conversion with an intercultural exploration of the Maasai concept of the “firstborn” in dialogue with the Christological uses of “firstborn” (πρωτότοκος) in the NT (99–105). Acknowledging that the Maasai “ELCT is not at ease, yet, with contextual theology” (105), he points the way forward for “Maasai hearers, readers, preachers, and interpreters” to be enabled to “relate the message of Christ to their own framework of thought” while remaining thoroughly within “the realm of Christian faith and tradition” (105). Note as well how Justo lists “Maasai hearers” first, before “Maasai readers.”

7. Knut Holter, “Maasai and Ancient Israelites”

Anyone who has spent any time with the Maasai will appreciate the full title of this next essay, “The Maasai and the Ancient Israelites: Religio-Cultural Parallels.” When my wife and I moved, with our young children, to live among the Maasai adjacent to the Maasai Mara over 14 years ago, it was not long before we noticed many similarities between the Maasai and the ancient Israelites whom we read about in the biblical texts. We were not the first. In 1910, Moritz Merker published an ethnography of the Maasai in which he went so far as to claim that the Maasai must be either Jewish or “one of the so-called lost tribes of Israel” (109). In popular discourse, much has been made of these similarities. Some, following Merker, have argued for a genetic approach, i.e., that the Maasai are the lineal descendants of ancient Israel. Holter offers a robust critique of three versions of this interpretation (108–112). Others take a thematic approach, noting that such similarities can arise from “more or less corresponding socio-economic conditions” (112–113); Lyimo-Mbowe and Nkesela’s contributions to this volume take this approach. Leonard A. Mtaita, a Maasai Lutheran theologian, provides an earlier example of this framework, investigating a “conscious contextualization of faith and church in relation to doing mission with the Maasai” (113; see Mtaita 1998). Others, such as Justo in this volume, have pushed this socio-economic connection further with a deeper dive into biblical studies. The chapter concludes by noting that the thematic approach to these similarities “has a great potential—partly for ‘enculturating’ biblical texts and motifs in Maasai culture, and partly also for facilitating a deeper understanding of these biblical texts and motifs” (117).

8. Beth E. Elness-Hanson, “YHWH in the Kimaasai Bible”

This chapter was the first one I read in this volume, as I have been deeply invested in the relevant issues. As I observe elsewhere,

The divine name, YHWH, in the OT is typically rendered as Lord in English translations, with the small caps distinguishing the divine name from various titles (such as Adonai) which are translated as Lord. The then-current edition of the Maa Bible (1991) obliterated this distinction by translating both Lord and Lord as Olaitoriani (the Maa version was translated from the English RSV with no reference to the biblical languages); olaitoriani is derived from the Maa verb aitore, “to rule over, to be in charge” (Barron 2021c).

When I served as a Bible translation consultant with The Bible Society of Kenya for their project of revising/correcting the Maa Bible (2011–2017), I made a case for doing something different (see Barron 2021b, 9–11 and 13–14). I was unsuccessful, and the 2018 edition of the Maa Bible retained the usage of Olaitoriani. In this chapter, Elness-Hanson makes a stronger case than I had been able to make that rendering YHWH as Olaitoriani in OT texts is both unsuitable and limiting. (Disclosure: though I had quite forgotten the matter until I read this chapter, Elness-Hanson had actually consulted with me on this issue, and on p. 138 she cites an email I wrote to her in 2013.)

In important ways, using olaitoriani to render God’s divine name, the title Adonai, and other titles of lordship (including for human masters) serves “to reduce the dynamics of Hebrew vocabulary and flattens the dimensions of the text” (135). “At the core of the identity represented by the name YHWH is the relationship with a covenantal, reconciling, and relentlessly loving God. However, “the God who rules” does not adequately relay this in a Maasai context” (137).

I could not agree more. I only wish that the entire revision committee of The Bible Society of Kenya had had an opportunity to read this essay or, better, to discuss this issue with Elness-Hanson before the 2018 edition of the Maa Bible had gone to press.

9. Jesse N. K. Mugambi, “Bible and Ecumenism”

In this chapter, “The Bible and Ecumenism in African Christianity: In honour of Professor Knut Holter,” Professor Mugambi “explores usage of the Bible” specifically “as the scriptural foundation of the Christian faith” (147). He expresses hope that other scholars will follow the example of the many books resulting from Holter’s teaching and research (including the three volumes reviewed here). He rejoices in John S. Mbiti’s signal achievement as “the first African scholar to translate the entire New Testament from original Greek Text into an African language as the sole author” (149), which he considers as a primary mark of maturity for African Christianity (149–150). Blaming the ignorance on the part of translators of either the biblical languages and/or of the target language (with its culture), Mugambi notes that for many Africans the Bible is considered an alien book. Nonetheless, for African Christians the Bible retains a “unifying and indispensable function … in the Christian faith” (158). Believing that the participants of The Bible and Maasai Project have set an example for others, he encourages others concerned how “the Bible is used in the African context” (169) to “go and do likewise!” (179).

Maasai and the Bible Project: Observations and Conclusions

Each of these four volumes clearly demonstrates that “the Bible has the potential to strengthen” Maasai culture (Nkesele 2020, 213) and thus, by extrapolation, African culture in general. The books show how “the concepts of authentically Christian and authentically African are complementary rather than contradictory” (Barron 2021c). While these publications have some room for improvement (see my critique, Barron 2021c), I wholeheartedly recommend all four of these books as “must reads” for anyone working in missions or in theological education among Nilotic groups generally and the Maasai and Samburu specifically. I likewise recommend then for anyone, African or otherwise, who works with African Christians or with African churches.

Ordinary Reader Hermeneutics Is Vernacular

It is increasingly recognized within the discipline of African Biblical Hermeneutics that “both scholarly readers and the ordinary readers [are] capable hermeneuts” (Kĩnyua 2011, 2; see also West 1999, Elness-Hanson 2017, Lyimo-Mbowe 2020, Nkesela 2020). Ordinary readers, of course, are those who are not part of the scholarly guild or who otherwise lack training in interpreting biblical texts. As someone who is a scholarly reader with a commitment to equipping ordinary readers, I must ask myself whether “our biblical scholarship is committed more to our (elitist) peers than to people on the grassroots” (Masenya 2016, 4). It is also apparent that ordinary readers are most at home when approaching the biblical text in their own vernacular. Kwame Bediako saliently reminds us that “Mother tongues and new idioms are crucial for gaining fresh insights into the doctrine of Christ” (Bediako 1998, 111)—true not just for Christology but for biblical interpretation generally. As a foreign missionary myself, I remember that access to vernacular Bible translations necessarily results in African hermeneutical agency as well as placing foreign missionaries in a subordinate position to the local Christians (Sanneh 2009, 196; West 2018, 245). I am a partner of ordinary Maasai readers, and I am not in charge.

An Enkiteng Hermeneutic?

After observing that “the Bible in African languages remains the most influential tool of rooting the Bible in African consciousness,” Masenya (Ngwan’a Mphahlele) and Ramantswana go on to note “the limitations of foregrounding the Bible as written word within aural contexts” (Masenya and Ramantswana 2015, 5) of Africa. These twin realities loomed large for my wife and me when we moved in 2007 to “the bush” of Maasai Land in southern Kenya in order to assist the local churches with curriculum development. Our work must be grounded in the Maa translation of Scripture and must take account of the importance of orality in Maa culture. We must not be concerned only with the “ordinary Maasai reader” but primarily with “the ordinary Maasai listener.” The first matter at hand, of course, was to learn the Maa language. But eventually we had to begin creating curricula! We had previously taught at a small Bible institute in South Africa (2000–2001). We had seen that simply transplanting western ways of thinking and studying was not working. Pastors could be trained to preach a good sermon in English, but they weren’t being equipped to exegete Scripture in their own vernacular. (Of course, we have also seen U.S.-American seminary grads who could pontificate doctrine but who couldn’t connect with the ordinary readers and hearers in the pews of their churches.) So we were committed to finding a different way. First of all, we knew that Maasai church leaders needed to teach in the Maa language and as Maasai Christians instead of just reproducing a British style lecture. What would that look like?

We learned that, traditionally, the Maasai teach and engage in character formation through storytelling, parables, drama, and proverbs—and never through a western style lecture! (Etymologically, a lecture is the act of reading something that had been written. In many Kenyan schools and universities, lectures are the act of a lecturer reading his or her lecture notes, which were written by someone else. So from start to finish a lecture is simply foreign to Maasai culture.) This same teaching style is common across much of Africa. Kĩnyua, an Agĩkũyũ biblical scholar from Kenya, proposes that scholarly readers and ordinary readers alike should “engage the Bible through the language of the African theatre and storytelling” (Kĩnyua 2011, 322). Why, we wondered, weren’t we seeing that in the local Maasai congregations? Why were Maasai Christians instead trying to imitate foreign models? We set out at once to learn as many traditional Maasai stories and proverbs as we could and to learn traditional Maasai modes of communication. Effective communication had to be appropriately contextual for the culture. This brings us to enkiteng.

Enkiteng is the Maa word for “cow.” Traditionally, the Maasai are semi-nomadic herdsfolk, raising cows, sheep, and goats. Culturally, cows are the most important animal. To be wealthy means to have cows and children. The Maasai will see the wealthiest (in others’ eyes) world leader who has neither cows nor children as impoverished. The plural of enkiteng is inkishu. Interestingly, the Maa word for “life” is enkishui. This linguistic similarity points to the integral and intimate connection in the worldview of the Maasai between cows and human life.

So when we were asked to teach an “inductive Bible study” course at a local Discipleship Training School (since rebranded as the Maasai Discipleship Training Institute), we started with a parable about cows. Cows, of course, are ruminants—they chew the cud. They don’t just swallow chunks of food down without chewing. They chew it thoroughly before swallowing. Later, they regurgitate the grasses they have eaten and chew the cud a second time. In that way they can extract all the goodness out of the grass—something that elephants, for example, cannot do, as even a casual comparison of cow and elephant dung will reveal. Likewise, a good shepherd (the most common Maasai designation is olchekut (for men) or enchekut (for women), both referring to a shepherd of livestock generally, not just of sheep) knows the importance of pasture rotation. Only grazing in one spot is bad for the pasture and eventually bad for the cows as well. Instead, it is necessary to migrate to new pastures to allow the grass to recover at the former one. In the same way, Christians should intake Scripture as the cow intakes grass, taking time to “chew the cud.” Similarly, Christians should “graze” throughout the whole of Scripture, not just from their favorite Gospel or Epistle.

It is worth mentioning here that “eating” or “chewing” is a common idiom in Maa. Where Hebrew speaks of “cutting a covenant,” Maa speaks of “eating an oath.” Traditional greetings include elaborate exchanges of “eating the news.” When you want to catch up with someone, you will invite them, mainosa ilomon! (“let’s eat the news!”); the word ainos is one of the verbs for eating; enkinosata refers to the act of eating. Thus we speak of enkinosata Ororei le Nkai, “eating the Word of God,” anaa enkiteng nanyaal ing’amura, “as the cow chews the cuds.” (The Maa phrases meaning “eating the news,” using the verbs ainos or anya, are usually translated as “chewing the news” in English, though anyaal is the proper term for “to chew;” this is probably due to the influence of the English idiom of “chewing the fat.”) We have developed this intricate subject more fully in Maa elsewhere (e.g, Barron and Barron 2008, 27–28 and 48–57).

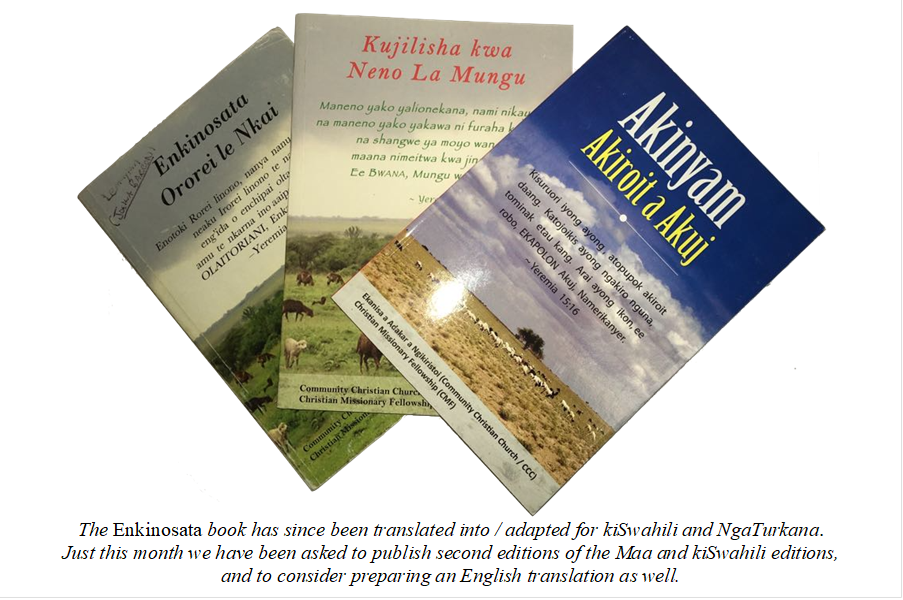

That first course on Enkinosata Ororei le Nkai was so well received and proved so helpful that we developed it into a full curriculum which went to press in December 2008. The full title translates to “Eating the Word of God: Comprehending the Holy Bible: How You Can Really Listen to the Word of God in the Bible so that You Grasp Its Meaning.” We created it with the understanding that for the majority of the Maasai congregants in rural congregations orality is far more important than literacy, especially among the older generations. Sometimes the teacher or preacher might be the only reader in the gathering. (In other words, we took the African contextual reality of the importance of orality quite seriously.) After an introductory “instructions for teachers” which explains how to use the following lessons and demonstrates the importance of communicating in a Maasai fashion, there are ten lessons (though most Maasai teachers take more than ten sessions to teach the material). All the lessons are parable based, using parables which arise naturally out of Maa culture—just as the parables of Jesus rose naturally out of his surrounding cultural context—and include the frequent use of enkiguran (“drama”). We give examples of how one may, as a Maasai, “chew the cud” of the biblical texts in order to direct Maa cultural questions to Scripture.

Charles Nyamati, the Tanzanian theologian, taught that “the Christian has something to learn from the traditional African; not in the sense of new doctrines, but in the sense of new insights and new ways of understanding God” (1977, 57); I would add “new insights and new ways of understanding Scripture.” As we worked on the Enkinosata project and as I have continued to develop in my other research and teaching what I have here called an enkiteng hermeneutic, I have tried to encourage Maasai believers “to embrace and celebrate the use” of their Maa language in their biblical interpretations and in their theologizing and “to make full use both of Maa culture and language” in intersection with the Scripture as they build up the Church of Christ in Maasailand (Barron 2021b, 15). I hope that as a professional reader I thus have been able to join Maasai indigenous and ordinary readers of Scripture as “partners in an ethical way of relating the biblical texts to the context” (Nkesela 2020, 10).

Conclusion

Like Masenya and Ramastwana, I am convinced that “For Africans to contribute meaningfully in the global village, they are not required to abandon their African optic lenses. Rather, it is through such lenses that they are called upon to contribute to the global intercultural theological or biblical hermeneutics table as equal partners” (Masenya and Ramantswana 2015, 3). Through this enkiteng hermeneutic—an intercultural Maasai African Biblical hermeneutic—Maa culture and the cultural sensibilities of the ordinary readers among the Maasai people are privileged. This “encounter between the Maasai and the Bible provides conceptual tools for strengthening not only [Maasai culture] but also African culture and identity more generally” (Nkesala 2020, 194), enabling Maasai Christians to translate “biblical truth into [the] vernacular categories and worldview” (Shaw 2010, 167) “of the broader Maa culture” (Barron 2021a, 5). Masenya and Ramantswana correctly assert that “the survival of African Biblical Hermeneutics depends on African biblical scholars digging more wells from which Africans will quench their thirst” (Masenya and Ramantswana 2015, 11). Through an enkiteng hermeneutic, I have seen numerous such new wells flow with the enkare namelok (“sweet water”) of new insights for Maasai Christianity (for some examples of possibilities of such new wells, see Barron 2019 and Barron 2021b).

References

Barron, Joshua Robert (2019). “Lessons from Scripture for Maasai Christianity, Lessons from Maasai Culture for the Global Church” Priscilla Papers 33(2): 17–23.

_____ (2021a). “Conversion or Proselytization? Being Maasai, Becoming Christian” Global Missiology 18(2): 12 pages.

_____ (2021b). “My God is enkAi: a reflection of vernacular theology” Journal of Language, Culture, and Religion 2(1): 1–20.

_____ (2021c, forthcoming). “A Four-in-One Book Review: On the Bible and Intercultural Hermeneutics among the Maasai” International Review of Mission 110(2): pagination forthcoming.

Barron, Joshua [Robert] and Barron, Ruth (2016). Akiyen Akiroit a Akuj. Translated by Simon Eipa. Edited by Joshua Barron and Simon Eipa. Lodwar, Kenya: Community Christian Church.

_____ (2008). Enkinosata Ororei Le Nkai: Enkibung’ata Bibilia Sinyati: Eninko Teninining Ororei le Nkai te Bibilia Nimbung Enkipirta enye: Inkiteng’enat Tomon. Nairobi: Community Christian Church.

_____ (2015). Kujilisha kwa Neno La Mungu. Translated by Joseph Okulo, Elijah Ombati, et al. Nairobi: Community Christian Church.

Bediako, Kwame (1992). Theology and Identity: The impact of culture upon Christian thought in the second century and modern Africa. Regnum Studies in Mission. Oxford: Regnum Books.

_____ (1998). “The Doctrine of Christ and the Significance of Vernacular Terminology” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 22 (3): 110–111.

Biblia Sinyati: te nkutuk oo lMaasai o natisiraki eng’ejuk (2018). Nairobi: The Bible Society of Kenya.

Biblia Sinyati: te nkutuk oo lMaasai o sotua musana o sotua ng’ejuk (1991). Nairobi: The Bible Society of Kenya / Dodoma: The Bible Society of Tanzania.

Elness-Hanson, Beth E. (2017). Generational Curses in the Pentateuch: An American and Maasai Intercultural Analysis. Bible and Theology in Africa 24. Edited by Knut Holter. New York: Peter Lang.

Hodgson, Dorothy L. (2005). The Church of Women: Gendered Encounters between Maasai and Missionaries. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Holter, Knut (2008). Contextualized Old Testament Scholarship in Africa. Nairobi: Acton Publishers.

_____, ed. (2006). Let My People Stay! Researching the Old Testament in Africa. Nairobi, Acton Publishers.

_____, ed. (2000). Yahweh in Africa: Essays on Africa and the Old Testament. Bible and Theology in Africa 1. Edited by Knut Holter. Peter Lang.

Holter, Knut, and Justo, Lemburis, eds. (2021). Maasai Encounters with the Bible. Nairobi: Acton Publishing.

Kĩnyua, Johnson Kĩriakũ (2011). Introducing Ordinary African Readers’ Hermeneutics: A Case Study of the Agĩkũyũ Encounter with the Bible. Religions and Discourse 54. Oxford: Peter Lang.

Liew, Tat-siong Benny, ed. (2018). Present and Future of Biblical Studies: Celebrating 25 Years of Brill’s Biblical Interpretation. Leiden: Brill.

Lyimo-Mbowe, Hoyce Jacob (2020). Maasai Women and the Old Testament: Towards an Emancipatory Reading. Bible and Theology in Africa 29. Edited by Knut Holter. New York: Peter Lang.

Masenya, Madipoane (2004). How Worthy Is the Woman of Worth?: Rereading Proverbs 31:10–31 in African South Africa. Bible and Theology in Africa 4. Edited by Knut Holter. New York: Peter Lang.

Masenya (Ngwan’a Mphahlele), Madipoane (2016). “Ruminating on Justin S. Ukpong’s inculturation hermeneutics and its implications for the study of African Biblical Hermeneutics today” HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72 (1): Article # 3343, 6 pages.

Masenya (Ngwan’a Mphahlele), Madipoane and Ramantswana, Hulisani (2015). “Anything new under the sun of African Biblical Hermeneutics in South African Old Testament Scholarship?: Incarnation, death and resurrection of the Word in Africa” Verbum et Ecclesia 36 (1): Article #1353, 12 pages.

Mburu, Elizabeth (2019). African Hermeneutics. Carlisle, England and Bukuru, Nigeria: HippoBooks.

Mtaita, Leonard A. (1998). The Wandering Shepherds and the Good Shepherd: Contextualization as the Way of Doing Mission with the Maasai in the ELCT – Pare Diocese. Makumira Publication 11. Usa River, Tanzania: The Research Institute of the Makumira University College.

Nkesela, Zephania Shila (2020). A Maasai Encounter with the Bible: Nomadic Lifestyle as a Hermeneutic Question. Bible and Theology in Africa 30. Edited by Knut Holter. New York: Peter Lang.

Nyamiti, Charles (1997). “The Doctrine of God” Chapter 6 in John Parratt, ed., A Reader in African Christian Theology. 2nd ed. London: SPCK, 57-64.

Parratt, John, ed. (1997). A Reader in African Christian Theology. 2nd ed. International Study Guide 23. London: SPCK.

Peter Lang (2021). “Bible and Theology in Africa” Peter Lang website, https://www.peterlang.com/series/6772 (accessed October 19, 2021).

Priest, Doug, Jr. (1990). Doing Theology with the Maasai. Pasadena, California: William Carey Library.

Rhoads, David (2009). “Biblical Performance Criticism,” in James A. Maxey, From Orality to Orality: A New Paradigm for Contextual translation of the Bible. Biblical Performance Criticism Series Vol. 2, ed., David Rhoads. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, ii.

Sanneh, Lamin (2009). Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture. 2nd edition, revised and expanded. American Missiology Society 13. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books.

Shaw, Mark (2010). Global Awakening: How 20th-Century Revivals Triggered a Christian Revolution. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic.

Sugirtharajah, R. S., ed. (1999). Vernacular Hermeneutics. The Bible and Postcolonialism 2. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press.

Ukpong, Justin S. (1995). “Rereading the Bible with African Eyes: Inculturation and Hermeneutics” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 91 (3): 3–14.

Walls, Andrew F. (1990). “Conversion and Christian Continuity” Mission Focus 18(2): 17–21.

_____ (2002). “The Ephesians Moment: At A Crossroads in Christian History.” Chapter 4 in The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission and Appropriation of Faith. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 72-81.

_____ (2004). “Converts or Proselytes? The Crisis over Conversion in the Early Church” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 28(1): 2–6.

_____ (2007). “The Ephesians Moment in Worldwide Worship: A Meditation on Revelation 21 and Ephesians 2” in Charles E. Farhadian, ed., Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices. Calvin Institute of Christian Worship Liturgical Studies Series, ed., John D. Witvliet. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans.

_____ (2012). “Worldviews and Christian Conversion,” Chapter 11 in John Corrie and Cathy Ross, eds., Mission in Context: Conversations with J. Andrew Kirk. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 155–166.

West, Gerald O. (1999). “Local is Lekker, but Ubuntu is Best: Indigenous Reading Resources from a South African Perspective” in R. S. Sugirtharajah, ed., Vernacular Hermeneutics. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 37–51.

_____ (2018). “African Biblical Scholarship as Post-Colonial, Tri-Polar, and a Site-of-Struggle,” in Tat-siong Benny Liew, ed., Present and Future of Biblical Studies: Celebrating 25 Years of Brill’s Biblical Interpretation. Leiden, Brill, 240–273.