Prerequisites for Movements? Questioning Two Widely-Held Assumptions

Emanuel Prinz, with Dave Coles

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, January 2022

Abstract

The data presented in this article challenge two assumptions that have been held widely among movement thinkers and practitioners: “Movements can only happen after lengthy previous gospel proclamation, by the actual movement catalyst or by preceding pioneers”; and, “Movements only occur among people groups that are receptive to the gospel.” Both notions are challenged by the data of recent research into 35 different movements.

Key Words: catalyst, movement, pioneer

Introduction

This study’s recent research among 35 movements in 15 different countries suggests fresh consideration of two very important questions: “Must a movement build on lengthy previous gospel proclamation?” and “Do movements only occur among receptive people groups?” Commonly held assumptions of affirmative answers to these questions may unnecessarily have hindered efforts to initiate movements, in particular among unreached Muslim peoples.

The movements examined in this study represent the major regions of the Muslim world, including West Africa, East Africa, the Arab World, Turkestan, South Asia, and Southeast Asia (also referred to as Indo-Malaysia). Most movements researched took place in Indonesia (18). Other countries with multiple movements included in the study are India (3), Jordan (2), Ethiopia (2), and Bangladesh (2). One church planting movement is underway in each of the following: Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Mozambique, Sudan, Pakistan, China, and Myanmar. One movement has grown from Kenya across the borders into Somalia and Tanzania.

Of the nine regions of the Muslim world that Garrison describes as the different Rooms in the House of Islam (2014), only North Africa and the Persian world are not represented in this study. (The initial pioneer leaders of the two movements in these regions have passed on and were thus unable to contribute to the research.) The movement among the Kabyle-Berber of Algeria was catalyzed in the 1970s (Marsh 1997; Blanc 2006), and the one among the Persians of Iran in the 1980s (Garrison 2014, 90-94, 130-141).

Biblical and Theological Foundations

The research for this study rests on the conviction that three factors influence the emergence or impediment of movements: the sovereignty of God, the receptivity of the gospel’s recipients, and the person (traits) and ministry (competencies) of the pioneer (Packer 1961; 2008; Clark 2006; Snyder 2010).

The first factor, the sovereignty of God, eludes all human investigation (Luther [1516] 1937; Calvin [1536] 1989; Grudem 1994). This elusiveness reflects the Apostle Paul’s conviction, “How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!” (Rom. 11:33; all Scripture quotations are from the ESV). This study rests on the theological foundation of God’s sovereignty and human responsibility.

God determines “all things” (Eph. 1:11) according to his perfect, eternal will and plan. At the same time, humans are responsible for their every action, and their decisions are genuine decisions: they have a real impact on the outcome of events (Grudem 1994, 315-337). These convictions mean that the following propositions are equally true (Packer 1961; 2008; Clark 2013):

• Wherever people come to faith in Christ Jesus, it is ultimately because of God’s sovereign election and predestination. Wherever a movement emerges, God has sovereignly willed for it to happen.

• Each person who hears the gospel (assuming sufficient maturity and mental faculties) has the capacity to make a genuine decision in rejecting or accepting Jesus Christ, a decision for which they will be held responsible. Wherever the message of Jesus Christ has been adequately proclaimed and people have not received it, they have willfully rejected the gospel.

• All pioneers make genuine decisions about how to live their lives and carry out their ministries among the societies where they live and serve. Those decisions can be conducive to or impede the catalyzing of a movement (Goldmann 2006).

The second factor affecting effective catalyzation of a movement is the receptivity of the people among whom the good news is spread. The Bible teaches that the amount of fruit may not lie in the effort of the sower, but in the fertility of the soil (see Matt. 13:23). A rough survey of the world today confirms this teaching. Some people groups and regions show great receptivity, and almost every church planting team serving among those groups and regions sees fruit. Examples among Muslim peoples include Albanians and the Kabyle Berbers in North Africa (Mandryk 2010, 95, 98; Blanc 2006). Some other people groups seem so unreceptive that church planting teams have seen hardly any fruit at all, for example the Malay and Bruneians (Mandryk 2010, 557, 172).

The third factor related to catalyzing a movement is the person of the pioneer. While affirming the above theological factors, the pioneer leader remains a critical factor in whether or not a movement emerges. We teach what we know, but we reproduce who we are. Modeling plays an absolutely essential role in Christian discipleship (2 Tim. 3:10). Thus, the traits of pioneers will influence their effectiveness.

Since God has chosen to use human agents to take the good news of his kingdom to mankind, the person of the disciple maker impacts the results in pioneer church planting. The Apostle Paul’s sequential chain in Romans 10 seems to indicate the critical factor of the pioneering gospel messenger. Romans 10:14-15 outlines the chain that must occur for unreached peoples to come to faith in the gospel:

1. God sends (ἀποσταλῶσιν - apostalosin) a “sent one” (the meaning of “apostle” or “missionary”).

2. The sent one preaches.

3. The unbeliever hears.

4. The unbeliever believes.

5. The unbeliever, now a believer, calls on the name of the Lord.

6. The believer is saved.

This chain of elements can be summarized in the rhetorical question, “How can they call on the Lord without the sent one—the pioneer?” They cannot! The person and ministry of the pioneer is essential.

The Apostle Paul, the ultimate model for all pioneers, describes the diligence of his own efforts, stating, “Like a skilled master builder I laid a foundation” (1 Cor. 3:10b). He refers explicitly to his skills; hence, skills do affect the outcome. “The fire will test what sort of work each one has done” (1 Cor. 3:13). A modern church planting team’s ministry will face a similar test. Accordingly, “what sort of work” a pioneer does directly affects whether or not that work will produce lasting fruit.

The Apostle Paul succinctly formulates the confluence of the divine and the human factors, and summarizes the theological foundation of this study, when referring to those who build God’s church as “God’s fellow workers” (1 Cor. 3:9). The Greek word used for fellow workers (sometimes translated “coworkers”) is συνεργοί, the source of the English word “synergy.” This study’s research builds on David Garrison’s assertion that effectively catalyzing a movement results from the synergy of the human element with the divine, “a divine-human cooperative” (Garrison 2014, 255). Consequently, this research particularly focuses on the person of the pioneer.

Must a Movement Build on Lengthy Previous Gospel Proclamation?

Many have thought that movements can only be catalyzed among people groups who have had many years of previous Christian work sharing the gospel (Livingstone 1993, 18). Some would express this assumption more moderately: movements seem highly unlikely to occur in pioneer situations. The biblical principle referenced is, “whoever sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and whoever sows bountifully will also reap bountifully” (2 Cor. 9:6). The oft-cited prime examples are the movement among the Kabyle-Berber in Algeria and the mid-to-late 1960’s mass movement to Christ in Indonesia. The movement among the Kabyle-Berber occurred in the 1970s after several generations of Christian witness with hardly any response at all, starting with the pioneer Charles Marsh nearly 50 years earlier in 1925 (Marsh 1970; Marsh and Verwer 1997). In Indonesia between 1965 and 1971 two million Muslims turned to Christ (Willis 1977), but only after more than three centuries of Christian missionary work in the country.

The data informing this study indicate that this notion should be reconsidered. Movement breakthrough does not necessarily require a long period of sowing. At the time of their participation in this study, the pioneer leaders and their teams had been ministering between two and 24 years since taking up residence among the people groups in which they were serving. One participant had an itinerant non-residential ministry approach, in which he did not live among his people group. Of those participants living among their focus people groups, the average length of ministry was 8.4 years.

The length of ministry among the people group before the first fellowship of Jesus followers started a daughter fellowship ranges from three months to 15 years. The birthing of the first second-generation fellowship is considered the tipping point, where reproduction begins happening and a movement is catalyzed. Six church planting movements took between only three and six months of ministry for that to occur. Sixteen movements took between one and three years to be catalyzed. Four movements took between four and eight years. In only two movements did that process take place between 11 and 15 years. Three survey participants were not able to answer precisely the question about when the movement was catalyzed. The average time between the pioneer leader arriving on the ground and the birthing of the first second-generation fellowship was only two years and seven months.

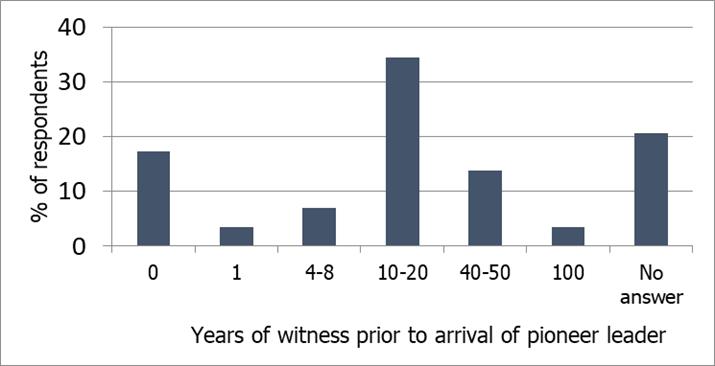

Figure 1: Time of Pioneer’s Ministry Prior to Movement Breakthrough

A related consideration is the number of years of any known gospel proclamation prior to the ministry of the pioneer leader and his or her team. This period ranged from zero to 100 years. Five participants answered zero: there had been no gospel proclamation at all prior to their arrival among the people group. For one movement it had been one year. For two movements it was four to eight years. The largest portion of participants, representing ten movements, answered between ten and “20+” years. Four movements had been preceded by 40 to 50 years of gospel proclamation, and in one movement it had been 100 years. Eight participants could not answer the question precisely, one describing it simply as “many” years. The median among those who answered the question was 15 years.

Figure 2: Year of Witness Prior to Arrival of Pioneer

This data are surprising in light of commonly held assumptions. It has been widely held that movements can only be catalyzed among people groups where there have been many years of previous Christian work sharing the gospel. The above figures of this study indicate that such a notion needs to be reconsidered. Some movements had been preceded by up to 100 years of gospel sowing, but others by only a few years—and others had had no previous sowing at all! These numerous examples show that only a small proportion of the movements among Muslims have built on a significant history of Christian work. Many of the movements have occurred without building on any foundation of previous work. They have been catalyzed by the very first pioneer among the people group.

This finding is new in the sense of being a first-time verification by specific data. However, the hypothesis had already been formulated in 2008 by an expert panel of church-planting movement (CPM) trainers from multiple regions globally. They concluded: “there seemed to be no difference in the … CPMs in terms of how long there had been gospel exposure in the area previously. For example, in both large and small CPMs, there were examples of longer and shorter histories of Christian work” (Stevens 2008, 3).

The data of this present study substantiate the earlier observations of those CPM trainers. Prior gospel witness seems to play little or no role in the likelihood of a movement being launched among a Muslim people group. This data-based conclusion debunks the heretofore common assumption that lengthy prior gospel proclamation must precede a movement being catalyzed.

Do Movements Occur Only among Receptive People Groups?

Concerning the second assumption, the supporting research data suggest no association between a people group’s gospel receptivity and the effective catalyzing of a movement among them. Movements are apparently unrelated to the overall receptivity of the people group.

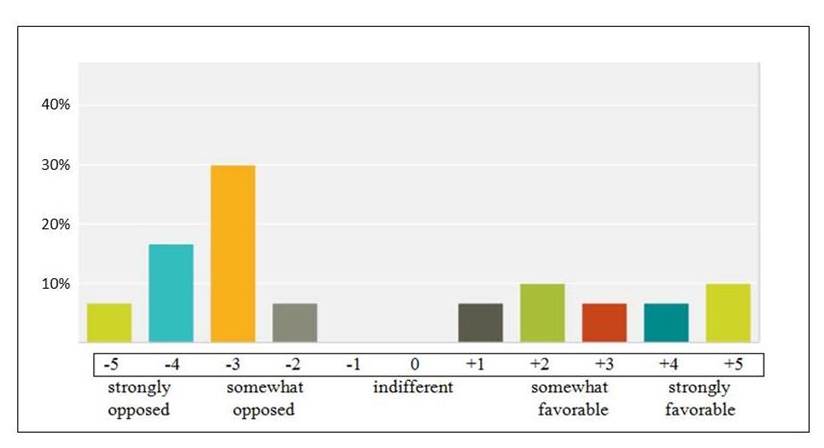

The receptivity of this research’s people groups toward the good news varied significantly at the time when the pioneer leaders first took residence among them. Participants used the Dayton Scale (Dayton and Fraser 2003), which ranges from -5 (strongly opposed) to +5 (strongly favorable) to measure the receptivity of societies and people groups toward the gospel. Among the people groups surveyed in this study, seven were assessed to have been strongly opposed (-5 and -4) to the gospel at the time when the pioneer leader first took up residence among the group. In 11 people groups, receptivity was assessed as somewhat opposed (-3 and -2). Two people groups were described as indifferent to the gospel (rated -1 to +1), while five were assessed as somewhat favorable to the gospel (+2 and +3). Only five out of 35 people groups were considered strongly favorable to the gospel when the pioneer leaders began their work among them. The following chart shows the nearly even distribution.

Figure 3: Receptivity of People Groups Toward the Gospel

The data show no correlation between gospel receptivity of a people group and the effective catalyzing of a movement among them. Movements seem unrelated to the overall receptivity of the people group. How can we explain this counter-intuitive reality?

Perhaps receptive pockets exist within most or all societies, including those having a low level of overall receptivity. Steve Smith’s research into church planting movements affirms this conclusion: “There may be hardened people groups, but in every one there are harvestable individuals” (Smith 2011, 83). Trousdale’s research comes to a similar conclusion, pressing further to note that often “the hardest people yield the greatest results” (Trousdale 2012, 155). This observation in many movements does not refer to gospel receptivity among entire people groups but to individuals and subgroups in society. The key open individuals are often referred to as “persons of peace,” based on Jesus’ instructions in Matthew 10 and Luke 10 (Trousdale 2012, 190; Watson and Watson 2014, 123-139). Trousdale also observes the principle that “sometimes the most difficult person to reach with the gospel will become the most dedicated follower of Christ” (Trousdale 2012, 161).

Conclusion

Any movement results from three factors: the sovereignty of God (which eludes human analysis and understanding), the receptivity of those who hear the gospel, and the pioneer who is responsible to share the gospel wisely. As the Apostle Paul experienced in the city of Corinth, some situations may manifest significant opposition to the gospel (Acts 18:6), yet the perspective of God’s eternal election reveals “many in this city who are my [God’s] people” (Acts 18:10).

The data of the research demonstrate that movements may happen irrespective of the receptivity of the overall population. This underscores the role of the pioneer, adding weight to the part he or she plays in catalyzing a movement. The data suggest a tentative hypothesis that certain pioneer leaders can become effective in catalyzing a movement, irrespective of the receptivity of the overall population in that community.

Since the divine element eludes human investigation, our understanding of the factors that contribute to movements leans even more heavily on the person of the catalyst. This focus confirms Greg Livingstone’s premise: “The human factor will be the variable between effective and ineffective church planting efforts” (Livingstone 1993, 26). Through demonstrating that neither length of prior gospel proclamation nor gospel receptivity are normative factors, this study points to pioneering movement catalysts as a key factor in catalyzing movements. This study and corresponding research (Prinz 2021) verify this conviction, showing a strong association between a catalyst who exhibits certain traits and competencies and the effective catalyzing of movements.

This article should encourage expectant faith and boldness among those the Lord is calling to catalyze a movement among the unreached. Neither limited length of gospel proclamation nor apparent lack of receptivity among a people group should diminish anyone’s faith that a movement breakthrough is possible and indeed may be imminent. The great need is a catalyst equipped with a set of particular traits and competencies who works in synergy with God as skilled master builder.

References

Blanc, Jean L. (2006). Algérie, tu es à moi!, signé Dieu (Algeria, You Are Mine!, Signed by God). Thoune: Editions Sénevé.

Calvin, Jean (1989 [1536]). Institutes of the Christian Religion. Trans. by Henry Beveridge. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Clark, Gordon H. (2006). Predestination. Unicoi: The Trinity Foundation.

Clark, Jeffrey W. (2013). If God Is in Control of Everything, Why Evangelize? The Evangelistic Theology of James I. Packer in Contemporary Literature and Practice. WaveCloud.

Dayton, Edward R. and Fraser, David A. (2003). Planning Strategies for World Evangelization. Eugene: Wipf & Stock.

Farah, Warrick, ed. (2021). Motus Dei: The Movement of God and the Discipleship of Nations. Littleton: William Carey.

Garrison, David (2014). A Wind in the House of Islam: How God is Drawing Muslims around the World to Faith in Jesus Christ. Midlothian: WIGTake Resource.

Goldmann, Bob. (2006). Are We Accelerating or Inhibiting Movements to Christ? Mission Frontiers 28, 8-13. Available online at http://www.missionfrontiers.org/issue/article/are-we-accelerating-or-inhibiting-movements-to-christ (accessed January 25, 2022).

Grudem, Wayne A. (1994). Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Livingstone, Greg (1993). Planting Churches in Muslim Cities: A Team Approach. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

Luther, Martin 1973 [1516]. Römerbriefvorlesung (Lectures on Romans). Hg. von S. Borcherdt & Georg Merz. München: Chr. Kaiser Verlag.

Mandryk, Jason (2010). Operation World: The Definitive Prayer Guide to Every Nation. 7th ed. Colorado Springs: Biblica Publishing.

Marsh, Charles (1970). Too Hard for God? Carlisle: Paternoster Publishing.

Marsh, Daisy M. and Verwer, George (1997). There’s a God in heaven: Life Experiences among North Africans. London: Gazelle Books.

Packer, James I. 2008. Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press.

Prinz, Emanuel (2019). Der Missionar den Gott zu Großem gebraucht (The Missionary Whom God Uses for Great Things). Nuremberg: VTR.

_____ [2022]. Movement Catalysts: The Profile of the Leaders God Uses to Catalyze Movements. (Forthcoming).

Smith, Steve and Kai, Ying (2011). T4T: A Discipleship Re-revolution. Monument: WIGTake Resources.

Snyder, Jason W. (2010). Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God: How God’s Irresistible Grace Compels us to Share. Dallas: Dallas Theological Seminary.

Stevens, M. (2008). “Focus on next steps…: Lessons from the multi-region trainers forum.” Unpublished paper, Singapore.

Trousdale, Jerry (2012). Miraculous Movements: How Hundreds of Thousands of Muslims are Falling in Love with Jesus. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

Watson, David and Watson, Paul (2014). Contagious Disciple Making: Leading Others on a Journey of Discovery. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

Willis, Avery T. (1977). Indonesian Revival: Why Two Million Came to Christ. South Pasadena: William Carey Library.