Meeting the Needs of Internally Displaced Christian Boko Haram Victims:

A Case Study of Mokolo in the Far North Region, Cameroon

Moussa Bongoyok

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, October 2023

Abstract

Since 2014, the Far North Region of Cameroon has experienced regular attacks from Boko Haram and, more recently, the Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP). These attacks have affected followers of all three major religions in the region, but Christians have been hit the hardest. Many have been forced to abandon their churches, villages, farms, and businesses and seek refuge in Mokolo, where they feel safe. While nonprofits and churches have quickly provided urgent needs like food, medical assistance, and shelter, many other crucial needs are often overlooked. This study dives deeply into the Mayo Tsanaga division victims' needs, offering insights into a holistic and sustainable approach to relief and aid. The article also highlights the importance of critical strategic preventive measures in at-risk villages and cities.

Key Words: aid, Boko Haram, Cameroon, holistic, Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP), Mokolo, persecution, relief, sustainable development, prevention

Introduction

Cameroon is a culturally and religiously diverse nation. This study focuses on the three northern regions of the country (Adamawa, North, and Far North) where Islam has impacted the populations the most. Of all three areas, the Far North was the very first to be exposed to Islam, and it is also the only one that has gone through severe attacks from Boko Haram (which means “foreign education is taboo” in the Hausa language) and, recently, the Islamic State of West Africa Region (ISWAP).

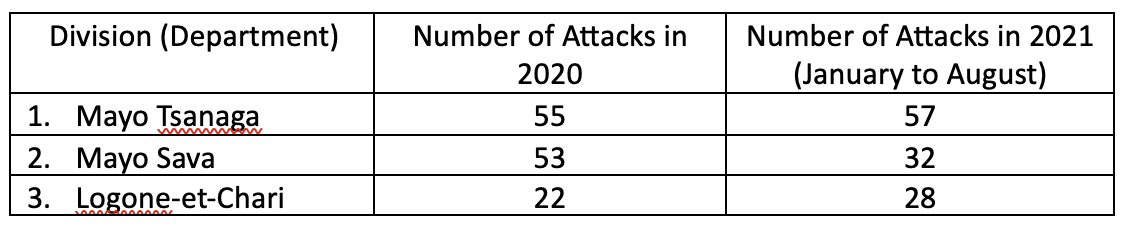

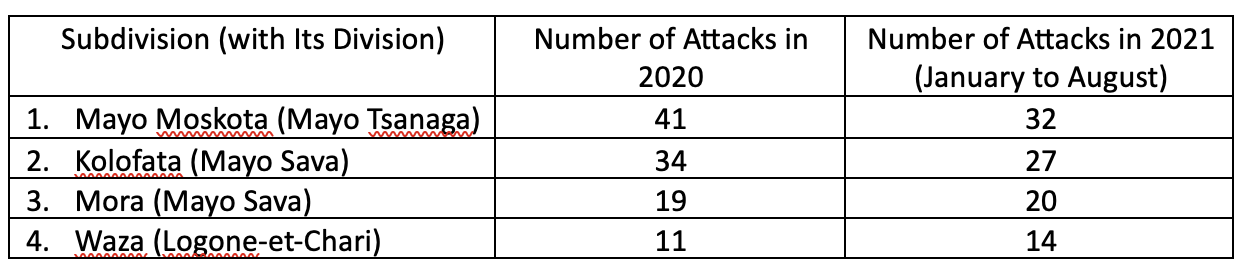

Three Far North divisions (or “departments”—what some English speakers might call “districts,” “counties,” or “divisions”) suffered the most from recurrent terrorist attacks: Logone-et-Chari, Mayo Sava, and Mayo Tsanaga. Although Boko Haram also carried out deadly terrorist attacks in 2015 in the Far North’s headquarters (capital) Maroua in the Diamaré division, thanks to God’s protection and the joint efforts of the Cameroon army and police placed under the leadership of the very apt Police Commissioner Hayam Martin, Maroua has not been attacked again.

To enhance the quality of its research, this study focused on one division, Mayo Tsanaga, because it is the most populated division and the one that lost the most significant number of lives and churches. For data collection, a combination of participant observation, interviews, and focus groups were used. Data analysis consisted of content analysis and discourse analysis. Due to space limitations this article primarily focuses on describing the geographic context, the historical background, some of the root causes of the terrorist attacks, the impact on churches and Christians resulting from these attacks, and some of the key felt needs of the internally displaced Christians. The article also suggests a preliminary proposal for a holistic and sustainable strategy for the displaced to survive.

Geographic Context

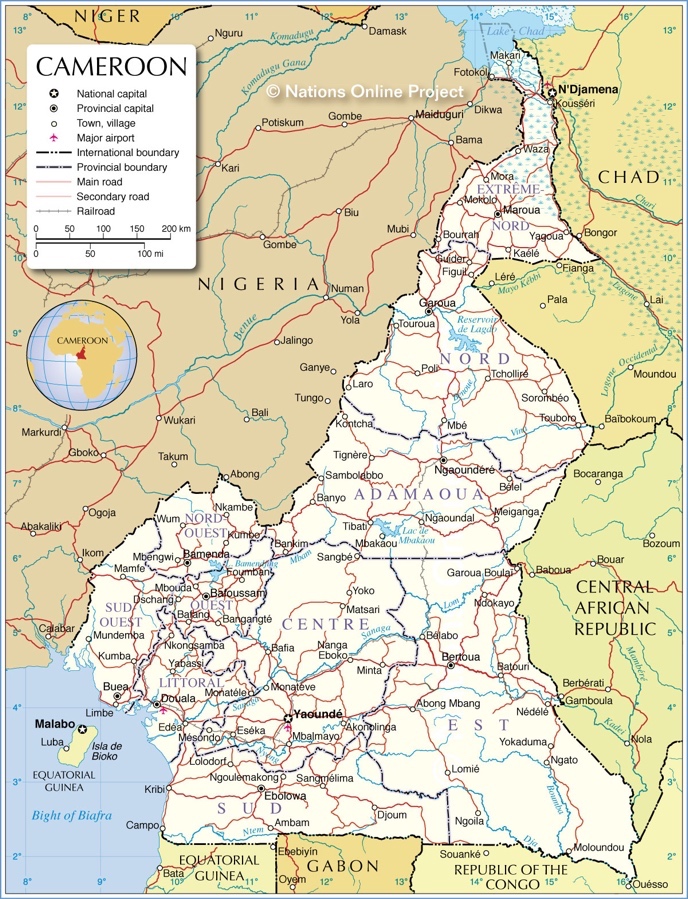

Cameroon is a West African nation surrounded by Chad in the North, the Central African Republic in the East, Gabon, Congo, Equatorial Guinea in the South, and Nigeria in the West. Of all its neighbors, it shares the most extensive border with Nigeria, as seen on the Figure 1 map below.

Figure 1: Administrative Map of Cameroon (Nations Online 2021)

Furthermore, in Maiduguri in northeastern Nigeria—which shares a border with Mayo Sava—Muhammed Yusuf founded Boko Haram in 2002 (Thurston 2018). Maiduguri is predominantly the territory of the Kanuri people, who also live in Cameroon, which explains why the movement spread quickly on the Cameroonian side. Maiduguri is also home to a large Mafa population, the largest ethnic group in the Mayo Tsanaga division. This explains why many fighters are very familiar with the languages, cultures, and hiding places at the border between the two nations, making it more difficult to control their movements in the context of asymmetric war.

The Mayo Tsanaga department, seen on the map of Cameroon’s Far North Region in Figure 2 below, has a Sahelian climate, with only three to four months annually of rain. The population relies on agriculture, but land is becoming scarce due to mountains, overpopulation, high illiteracy rate, and, to make the situation worse, overexploitation. Most of the population lives in abject poverty, which exposes the youth to the temptation of joining the ranks of terrorists, hoping they will have a better socio-economic condition.

Figure 2: Administrative Map of the Far North Region (NIS 2020, 4)

Religiously, Mayo Tsanaga is the first area in Cameroon where missionaries from the Sudan United Mission (SUM) settled and planted churches, primary and secondary schools, professional schools, Bible schools, and medical clinics. Under SUM leadership, the Bible was translated into the Mafa language and used by the SUM-birthed Union of Evangelical Churches in Cameroon as well as by other Protestant denominations, including the Baptists, Lutherans, Pentecostals, and Seventh-day Adventists. As a result, Mayo Tsanaga has one of the highest concentrations of churches in the whole of Northern Cameroon, and more Christians are in Mayo Tsanaga than followers of other religions. Historically, however, that was not the case.

Historical Background

The history of Cameroon is full of unexpected changes (Mveng 1984; 1985). In 1804, Usman dan Folio, a Pullo (Fulani), launched a jihad from neighboring Nigeria, significantly changing the northern regions of Cameroon. Predominantly inhabited by followers of African Traditional Religions before the jihad era, Islam was slowly but tactically imposed on rulers first and then the inhabitants of Cameroon’s northern half (current regions of Adamawa, North, and Far North). In fact, today’s Far North had been exposed to Islam much earlier through the Kanem Kingdom, which was formed in the seventh century and became Muslim in the eleventh century (Seignobos 2000, 44). Some sources date the Islamization of Kanem even earlier, in the ninth century (SOAS 2016.) In any case, Islam remained a minority religion, including in the Far North of Cameroon, until the beginning of the nineteenth century.

During the early nineteenth century jihad, even though Fulbe (Fulani) fighters took the leadership of most cities, rural areas remained closed to Islam. The dynamic started to change only when the German, British, and French colonial powers partnered with Muslim laamiibe (rulers) to achieve their agendas (Nkili 1984). Islam then gained ground in the region. Independence in 1960 did not change the movement of Islamization for the simple reason that the first President, El Hadj Ahmadou Ahidjo, was a Northern Muslim. During his long leadership (1960-1982), Islam flourished. “Non-Fulbe political leaders were encouraged to convert to Islam, supporting the myth of a homogenous Islamic North” (Regis 2003, 16). Northern Christians even went through severe persecution in the 1970s, not because the President ordered it but because some rulers took advantage of the political circumstances to push their religious agendas. Eventually, Christians were progressively free to live their faith and even evangelize and plant churches because of answers to prayers. It must be observed that God used key Christian leaders like Pastor Hans Eichenberger, whose advice Ahidjo took seriously (the author’s upcoming biography of Hans Eichenberger will provide more details).

If welcome change for Christians began during Ahidjo’s reign, it is really under the leadership of President Paul Biya, who has ruled the nation since 1982, that the Christian community in the three northern regions has thrived. When the systematic evangelism outreach “Cameroon for Christ” started in the year 1996 with three denominations joining forces—the Union of Evangelical Churches in Cameroon, the Lutheran Brethren Churches of Cameroon, and the Union of Baptist Churches of Cameroon—Christians enjoyed freedom and peace. Hundreds of new churches were planted in the Far North Region alone between 1996 and 2014.

Spiritually speaking the church was flourishing, but the overall social conditions of the Far North Region were showing signs of weaknesses and danger since independence. As Saïbou Issa puts it,

Since Cameroon's independence, the Far North has been the scene of arms, oil, drug trafficking, and various forms of violent banditry. This permanent insecurity is part of the long history of raids and pre-colonial and colonial wars in which this region has been the site, which still affects community relations. Community tensions were compounded around the 1980s by the phenomenon of highway robbers and hostage takers and land conflicts (Issa 2104, 581; my translation from the French original).

Unfortunately, the church became the first target of Bako Haram in 2014 and has given room to persecution, destruction, trauma, and chaos until now. The overall condition and future of the Sahel region are challenging, and there has been a rise in Islamism since the 1990s (Cincotta & Smith 2021, 9).

The Root Causes of Terrorist Attacks

In my PhD dissertation, I identify the major root causes of Islamism or Islamic fundamentalism in Northern Cameroon as historical, psychological, socioeconomic, doctrinal, ethical, and cultural (Bongoyok 2006, 38-50; cf. Ngassam 2020). The root causes of Islamic militantism in Borno State (Nigeria) and the Mayo Tsanaga division (Cameroon) are almost identical. This similarity leaves one wondering if the governments involved in the fight against religious terrorism in Cameroon, as well as the wider international community, have developed proper strategies in addition to and beyond the military responses that have been taken—in such a way that political, administrative, and religious leaders address all the leading root causes in an all-encompassing holistic strategy. Ignoring the other root causes of the current phenomenon besides those that have been dealt with by military means is a recipe for a disastrous failure. This understanding is particularly important in the city of Mokolo and its neighboring villages and towns.

The population of Mokolo, the headquarters of the Mayo Tsanaga division in the Far North Region of Cameroon, is about 300,000. Situated 80 km west of Maroua (headquarters of the Far North Region), the overall population of Mokolo and its environs is made up of Christians, Muslims, and followers of African Traditional Religions. The main local languages spoken in the area are Mafa and Fulfulde.

Mokolo is a hilly city, with agriculture being the area's main economic activity. Cash crops are cotton and soya beans, while the major food crops are millet, groundnuts, and maize. People also breed domestic animals as local economic savings. The area and other localities in northern Cameroon face severe land degradation due to the abusive use of chemical fertilizer, overuse of farmland, and deforestation from the uncontrollable destruction of trees for firewood. This land degradation causes soil erosion and soil fertility loss, crucial barriers to increasing agricultural yields. A decrease in agricultural products and the insufficiency of alternative sources of income are determinant factors for the perpetuation of poverty in this part of the country. It is worth noting that the Mayo Tsanaga division is one of the poorest areas in the poorest region (Far North) of Cameroon. The Far North has Sudano-Sahelian vegetation and climate and thus has little economic potential. A strong possibility is the exploitation of heretofore hidden natural resources.

Having noted such discouraging negatives, one can only salute the approach adopted towards the former Boko Haram and ISWAP fighters revolving around the following five key concepts: Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation, Reinsertion, and Reintegration. However, is that laudable approach sufficient to impulse a dynamic of sustainable holistic transformation in the communities and eliminate, or at least minimize, the current and future impact of terrorist attacks?

The Impact of Terrorist Attacks on Churches and Christians

Terrorism is a tragedy even for the perpetrators, in this case Muslim terrorists. Most Muslims in the Far North Region, and in the Mayo Tsanaga division, are in fact peaceful. They would not fight their neighbors in the name of a religious conviction. For this reason, many of them became targets of militant Islam. Although Boko Haram and ISWAP fighters have attacked Christians, Muslims, and followers of indigenous religions, the first targets of Boko Haram were Christians, foreign missionaries, churches, and Christian institutions. That strategy aligns with the ideology of war against the West and its multiple sources of influence, which radical Muslims see as dangerous and contrary to Islamic values. Although technically Christianity originated in the Middle East (not Europe or America), because Western missionaries were the first to spread the Good News in most African nations, confusion still exists in many Africans’ minds between Western civilization and the Christian faith. That confusion explains why churches and followers of Jesus suffered the most from terrorism in the Mayo Tsanaga division. The figures in Tables 1 and 2 below (Feubi 2021) show how more terrorist attacks have been directed against Mayo Tsanaga (and contiguous Mayo Sava) than any other division:

Table 1: Most Attacked Divisions (Departments)

Table 2: Most Attacked Subdivisions

These repeated attacks, sometimes carried out with incredible violence, have added to the misery of populations already disadvantaged by the ambient and anemic poverty among them. This situation should not only awaken the empathy of other Christians not directly affected by the attacks but should compel us to know more about the impacts of the attacks, the aid and assistance received, and above all the prospects for 'the future. Many have lost their houses, businesses, church buildings, and loved ones. Many lost their lives near Moskota, Koza, and Tourou, to name only these locations. The study underlying this article has involved a focus group of key displaced Christians to understand better the condition of those internally displaced and fearful for their own lives because of direct attacks on their communities.

Felt Needs of Internally Displaced Christians

Only someone who has lived through a sudden and violent attack in the middle of the night can truly understand the range of emotions an individual goes through, even when they are a believer in the Lord Jesus Christ. In desperate conditions some believers panic, others question God’s love and care, and others feel abandoned by their peers or neighbors. They leave their homes unprepared, traumatized, and empty-handed, sometimes leaving behind the elderly, handicapped, sick, weak, or sleeping family members. Those interviewed for this study were mostly internally displaced between 18 and 37 years old. It seems that many who were attacked were too young such that some did not realize the danger and simply escaped while others were killed or kidnapped to join the ranks of the fighters, become suicide bombers, or become the fighters' spouses against their will. Other victims were too old to run in the dark on a rocky and mountainous landscape, even when they were conscious of the deadly menace.

In their flight, some escapees went to Nigeria, Chad, Gabon, or major cities of Cameroon, mainly Maroua, Garoua, Touboro, Ngaoundéré, Bertoua, Yaoundé, and Douala. Others, too poor to travel far or obliged to care for family members left behind, stayed as close as possible to their villages or towns. Mokolo’s population has thus tripled in less than ten years to the point where it is challenging to purchase a piece of land or a farm due to scarcity and cost.

Needs have varied from person to person. Needs have also changed depending on the scope of the attack and the nature of loss (family members, neighbors, friends, parts of their body, house, church, legal documents, job, source of income, goods, peace, joy, etc.), the level of trauma, and the capacity to connect with family members or friends in the new location. Many have struggled with basic needs like shelter, food, school fees for children, and medical care. Others have been victims of depression, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder, with no Christian mental care specialist around to meet their felt needs. Others have needed re-training (learning new trades), having been farmers, herders, or in businesses but who lost their employment or even everything during an attack. Some have been gifted entrepreneurs and in need of financial support to get started and even create jobs for their fellow internally displaced. Even so, no bank would loan them money, and no Christian microfinance has met that specific felt need.

In this situation and others like it, the diversity of needs is such that a pastor or evangelist cannot fully help. It takes a team of believers with spiritual, social, professional, legal, medical, psychological, financial, logistic, and other relevant skills, expertise, and gifts to help the internally displaced. How does the church train and equip them for an intervention when needed? A robust contextual strategy is required.

Beyond Short-term Aid and Relief: A Holistic and Sustainable Development Strategy

While conducting individual interviews, our research team noted various situations. Here are what ten informants reported. Names and exact locations have been changed for security reasons.

1. John (male, age undisclosed)

Boko Haram fighters attacked his village eleven times between March 1 and June 27, 2022. They made an incursion on the village during the night and proceeded to loot the goods and food of the population. John lost clothes, food (millet, peanuts, and others), animals, and the property of the church, of which he is the pastor. The attacks did not impact him physically, but currently he is going through psychological trauma—including fear attacks that made him sick—from the stoppage in studies for his children and the loss of his property that made him dependent on aid. He has received no assistance to date. He is longing for spiritual and psychological comfort, securing the locality by strengthening the military presence, funding to restart his agricultural and pastoral activities, and emergency food aid.

2. Mary (female, age undisclosed)

The first attacks occurred in 2014. Since then, she has undergone multiple displacements that have led her to Mokolo. The attackers burst into the locality, burning houses, looting property, shooting civilians at point-blank range, and shelling women and girls. She lost everything. She left her village with only the clothes she had with her at the time of the attack. She had a month-old baby and was also pregnant. There was no physical impact but huge psychological impacts: fear and nightmares. She received one bag of millet. Apart from that, she has received nothing. She longs for a place to stay (family or house) and subsistence.

3. Peter (male, age undisclosed)

The first attacks took place in 2020 (two in total). The Boko Haram terrorists bombed a military camp. His neighbors were kidnapped. He lost his clothing and telephone. There was no physical impact on him, but huge psychological impacts: fear, nightmares, insomnia. The only assistance he received was one bag of millet in 2021. He is longing for food to eat (specifically millet), financial means to restart his economic activities, and clothing.

4. Adam (male, age undisclosed)

The first attacks took place in 2017 (twice), and another attack in 2022. In 2022 the Boko Haram attackers destroyed everything and burned down the village. He lost his house, food provision (millet), goats, lambs, and poultry. His family members only saved their lives. The attack had no physical impact but enormous psychological impacts: fear, nightmares, insomnia, his children dropping out of school, economic dependence, and lack of sustenance. Since that latest attack, he has only received one bag of millet. He needs millet for subsistence and financial means to restart his economic activities (to buy another mill to grind cereals), and clothing.

5. Abel (male, 18 years old)

Boko Haram did not reach his village directly; however, when they learned that a neighboring village was attacked, all the inhabitants of his locality fled as a preventive measure. There was no looting or bombing, but the village was emptied of its inhabitants. He had to abandon his house, land, and certain objects. There was no physical impact but enormous psychological impacts: fear, nightmares, insomnia, his children dropping out of school, economic dependence, and lack of sustenance. He has not received any assistance. He is longing for army protection and food.

6. Sarah (female, 35 years old)

The first attacks occurred in 2014 (twice), and one in 2022. There was bombing, looting, and killing, including his uncle's wife. In addition to losing a relative, he lost livestock, a sewing machine, clothing, and all household affairs. He did not have a physical injury, but he had enormous psychological impacts: fear, nightmares, insomnia, her children dropping out of school, economic dependence, and lack of sustenance. She received food from the host church every year. She longs for the return of security subsistence and resuming her sewing activities by purchasing another sewing machine.

7. David (male, 38 years old)

The first attacks occurred in 2018 (more than ten have already been recorded). The Boko Haram and ISWAP fighters set fire to their houses and perpetrated heavy shooting, looting, and kidnapping. As a result, his house and all its contents were completely burned. He lost stored food, livestock, and official documents, including his National Identity Card. He was not physically injured, but the attackers chased him. This all left him with huge psychological impacts: fear, nightmares, insomnia, his children stopping studies for a school year, economic dependence, and lack of subsistence. He received only one bag of millet in 2021. He currently needs millet for subsistence and financial means to restart his economic activities that stopped because of attacks, including trading in animals.

8. Lea (female, 35 years old)

The first attacks took place in 2018. Jihadists attacked with weapons, killing and looting. Her uncle's throat was slit. She lost her clothing. She was physically injured and there were huge psychological impacts: fear, nightmares, and insomnia. She received one bag of millet. She needs more millet for subsistence.

9. Richard (male, 37 years old)

The first attacks occurred on 12 September 2017 (six attacks have already been recorded). Boko Haram attackers surrounded the village. They burned houses. They took a 13-year-old hostage and killed two people. They burned his house, and he lost everything (livestock and other household affairs). There was no personal injury but enormous psychological impacts: fear, nightmares, insomnia, disruption of children's studies, and cessation of economic activities, including trade and agriculture. He received support for his children's schooling, clothing, food, and psychological and spiritual accompaniment from NGOs and the church. He needs land for agriculture and funding to revive his business. He also needs training to learn an income-generating trade.

10. Samuel (male, age undisclosed)

The first attacks took place in June 2022. Two neighboring villages were attacked. All the villagers left the locality. They abandoned their fields at the beginning of the rainy season. There was no physical injury but huge trauma: economic losses, school closures, the church emptied. He received did not receive assistance.

Considering the felt needs of the ten internally displaced believers listed above, short-term aid or relief must be improved. Some did not receive any help, and most got one bag of millet. Only one man received full support for his mental health, while nine out of ten did not have any support for a problem more complex than physical need (cf. Gingrich & Gingrich, 2017). It is possible and even necessary to provide better help than that, but doing so requires much prayer, thinking, analysis, planning, prevention techniques, safety measures, management, follow-up, discernment, wisdom, and above all genuine love.

The school I serve as President, Institut Universitaire de Développement International (IUDI), has started an experiment in two of the poorest villages of the Mayo Tsanaga department since 2019. IUDI asked the community leaders to select 20 unemployed young men and women and send them for training and mentoring. Forty people received six months of theoretical training in holistic and sustainable development, including entrepreneurship. They also did an internship for two months to have hands-on experience. IUDI asked each student to submit a proposal for an income-generating project that could be conducted within their village with a budget of $200. Our faculty members guided them in the process, and we gave the amount mentioned above to each of them. Some have already fructified the seed money and quadrupled it. Others are struggling but learning life-transforming valuable lessons in the process. The next stage is to grant more funds to graduates who show outstanding entrepreneurship skills so that they can grow more and even employ other youth in the community. Our administrative and faculty team commits to providing coaching and mentoring for at least two years until the trainees can thrive and multiply without any external help. So far the experiment is successful and can be used in similar contexts.

There is no single strategy that applies to all contexts. Strategic severe planning is necessary in each location and social group. However, this study would like to suggest that each strategy has the following essential aspects, organized with the full involvement and ownership of the community around the acronym “PREPARE”: Pray, Research, Elaborate, Partner, Act, Re-examine, and Equip.

Pray: It is necessary to ask God’s wisdom as His guidance is always the best in any situation.

Research: Research must precede planning. A SWOT analysis conducted by local community leaders who identify challenges and opportunities is strongly recommended.

Elaborate: A strategic plan with a team of resource people must be made.

Partner: Find a team of like-minded, qualified, and faithful Christians to meet holistic felt needs.

Act: Move from theory to practice, in words and deeds, with integrity and respectful fear of God.

Re-examine: Wise leaders should evaluate actions regularly and make necessary changes.

Equip: Equipping people for a sustainable development movement is the secret for lasting impact.

Conclusion

A closer look at recent human history shows that, despite all the hopes that humanity puts in science and technology, there are more questions than answers, more problems than solutions, more deadly rivalries than peaceful partnerships, more hatred than love, and more chaotic events than orderly ones. More religious persecutions will occur as society moves away from the only God and Creator. Christians should not be taken by surprise. The question is, how well are God’s people prepared not only to meet the immediate and holistic felt needs of people who come under Islamist terrorist attacks but also to equip them to be enabled to take care of themselves and even sustainably help others?

This article does not pretend to cover all the aspects and depth of the needs, or how to meet those needs, of displaced Christian victims of religious attacks. The article mainly presents the status of those who are displaced because of religion based violence. However, the study of the group of Christians internally displaced due to Boko Haram and ISWAP attacks in the Mayo Tsanaga division shows that it is essential to move quickly beyond the emergency and to plan prevention and sustainable development strategies in contexts and at-risk communities under recurrent attacks. Such planning is hard work but can be done with genuine love for God and neighbors.

References

Bongoyok, Moussa (2006). The Rise of Islamism among the Sedentary Fulbe of Northern Cameroon: Implications for Contextual Theological Responses. PhD dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary.

Cincotta, Richard & Smith, Stephen (2021). « Quel avenir pour le Sahel? » (“What Future for Western Sahel?”) Atlantic Council.

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/quel-avenir-pour-le-sahel/

Feubi, Steve (2021). « Boko Haram: le temps de la paix durable est-il arrivé? » (“Boko Haram: has the time for lasting peace arrived?”) Fadjiri Magazine. https://fadjiri.gredevel.fr/index.php/decryptage/item/27-boko-haram-le-temps-de-la-paix-durable-est-il-arrive

Gingrich, Heather Davediuk & Gingrich, Fred C., eds. (2017). Treating Trauma in Christian Counseling. Madison, WI: IVP.

Issa, Saïbou (2014). « Les cadres territoriaux du développement : frontières, gestion des conflits et sécurisation » (“Territorial frameworks for development: borders, conflict management and security”), in — Lemoalle J., Magrin G. (dir.), 2014 – Le développement du lac Tchad : situation actuelle et futurs possibles. Marseille, IRD Editions, coll.

Mveng, E. (1984). Histoire du Cameroun, Tome I (History of Cameroon, Vol. I). Yaounde: CEPER.

_____ (1985). Histoire du Cameroun, Tome II (History of Cameroon, Vol. II). Yaounde: CEPER.

Nations Online (2021). Administrative Map of Cameroon.

https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/cameroon-administrative-map.htm

Ngassam, N. R. (2020). « Historique et contexte de l’émergence de la secte islamiste Boko Haram au Cameroun » (“History and context of the emergence of the Islamic sect Boko Haram in Cameroon”), [Cahier Thucydide n° 24, Université de Paris II].

Nkili, Robert (1984). « Les pouvoirs administratif et politique dans la région nord du Cameroun sous la periode francaise 1919-1960 » (“Administrative and political powers in the North of Cameroon during the French Period 1919-1960”). Ph. D. dissertation. Aix-en-Provence.

National Institute of Statistics (NIS) (2020). « Enquête Complémentaire à la quatrième Enquête Camerounaise Auprès des Ménages (EC-ECAM 4) » (“Supplementary Survey to the Fourth Cameroonian Survey Among Households (EC-ECAM 4”). Republic of Cameroon, National Institute of Statistics. https://ins-cameroun.cm/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/RAPPORT-MONOGRAPHIE-EXTREME_NORD_VF.pdf

Regis, Helen A. (2003). Fulbe Voices. New York, New York: Routledge.

Seignobos, Christian & Iyébi-Mandjek, Olivier, dir (2000). Atlas de la Province de l’Extrême-Nord Cameroun (Atlas of the Far North Province of Cameroon). Marseille, IRD Editions.

SOAS (2016). “Borno and Old Kanembu Islamic Manuscripts.” SOAS Digital Collections. https://digital.soas.ac.uk/okim/about/

Thurston, Alexander (2018). Boko Haram: The History of an African Jihadist Movement Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.