More Local than the Locals:

An Ethnoscopic Analysis of a Philippine Seminary

Danyal Qalb

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, January 2024

Abstract

Most Filipinos are oral learners; seminaries in the Philippines are often copies of their Western counterparts with minimal contextualization. Using Thigpen’s four-step “ethnoscopic analysis,” I embark on a mission to examine theological education in the Philippines from cultural, scriptural, missiological, and pedagogical perspectives.

The findings from the ethnoscopic analysis prompted significant changes in my teaching approach and interactions with students at a local seminary. Join me on this journey as I explore improved ways for my students to learn and enjoy class more.

Key Words: mission, orality, pedagogy, theological education

Introduction

Since 2018, I have taught at a local seminary where I noticed students grappling with a curriculum akin to my educational experience in Germany. I have been trying to contextualize since I arrived in the Philippines in 2007. However, the seminary strongly emphasizes the Western educational system, training its students to adopt a Western way of teaching, thinking, and using English.

My students are not illiterate, but their comprehension of print-text is deficient, as they remain oral learners. I take you along in this article as I explore how theological education can become more engaging and effective for my students. I will look into cultural, scriptural, missiological, and pedagogical factors. Thigpen (2023) calls this four-step approach “ethnoscopic analysis” (30).

Education in the Philippines (Cultural Lens)

Filipinos highly value their children learning English, as I can attest from having two children in a Philippine school. As English is the language of well-educated, successful individuals (Box 2014, Chapter Perception of Literacy by Oral Societies, para. 1), a considerable portion of our curriculum is devoted to instructing students from rural areas in proper English. I agree that “English is becoming the lingua franca of Christianity in the twenty-first century” (Dörnyei 2009, 156). English is so ubiquitous in theological education in the Philippines that some see a need to add “theological English” to the curriculum (Gaston-Dousel 2011, 65). While acknowledging the benefits of using English, I also see how it poses a challenge for most of my students.

Oral learners start with real-life problems, or as Ong (2002) puts it, “Close to human to the lifeworld” (42–43). Kolb’s (1984) experimental learning theory is integral to the Philippines curriculum (Corpuz & Salandanan 2015, 198). When theory is not separated from praxis, learning becomes “truly effective” (Johnson 2017, 47). Connecting theory and praxis fits Filipinos’ learning preferences, but in reality practical aspects of experiential learning fall short. Instead, the focus is on input rather than the output or competencies of the students (Wiggins & McTighe 2005, 15). The taxonomy of Bloom et al. (1956) is used to guide teacher’s accessing their student’s learning achievements throughout the Philippines (Bilbao et al. 2015, 75–80). Teachers are encouraged to be “focused on higher-order thinking questions”; however, a recent study revealed that multiple choice is the most used evaluation tool by teachers, showing that in praxis lower-order thinking questions are prioritized (Mohammad et al. 2023).

Lingenfelter (2001) rightfully points out that contextualization is not applied to theological education (449–450). Western theological education is often embraced by local leaders and seen as authoritative (Mercado 2002, 302). Non-Western seminary students have come to expect Western ways of doing theology (cf. Bird & Dale 2022, 274). “Global institutions function as if oral communicators were not the majority, as if reading were the norm” (Thigpen 2022, 4). “Local trainers may have trained elsewhere and when they return to their local area, forget their old ways and use the foreign ways they were trained in” (Bird & Dale 2022, 283). When I see my students or talk to students from other seminaries, I too often feel that they are being educated away from their congregations. Madinger (2017; 2022) calls this phenomenon the Orality Gap (OG) (55–56, 51–52).

Jesus, the Master Teacher (Scriptural Lens)

The Bible offers numerous teaching examples, but I will only briefly touch on some methods Jesus used. He spoke in ordinary language, employed close-to-life stories, questions, and repetition, and focused on execution.

The New Testament was written in Greek, the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean of the time. However, Jesus spoke Aramaic, the language of the ordinary people, as evident in Mk. 5:41 and Mt. 27:46. Jesus was also aware of the literacy level of his audience. When quoting the Old Testament to ordinary people, he consistently began with the phrase “You have heard that it was said…” (Mt. 4:14; 5:21, 27, 31, 33, 38, 43; 8:17; 12:17; 13:35; 21:4; 27:9). In contrast, when addressing the chief priests, elders, Sadducees, scribes, or Pharisees, he employed the phrases, “It is written…” or “You have read…” (12:3, 5, 19:4, 21:13, 16, 42, 22:31).

Jesus’s stories related to the everyday experience of ordinary people of his time. In Lk. 15, Jesus shared three stories, illustrating God’s delight when even one sinner repents. People connected with these stories, and repeating the same truth in different narratives is a powerful tool for making that truth memorable. Unlike plain abstract truths taught as systematic theology, the narrative engages the heart; it “involves, disturbs and challenges us and as such is to be preferred” (Bausch 1991, 27).

When Jesus’s parents found him in the temple after a three-day search, he was listening to the teachers and asking them questions (Lk. 2:46). Some of his questions were rhetorical (Mt. 16:26), others responded to trick questions (Mt. 21:23-27, 22:15-22), and sometimes his questions challenged his followers (Mt. 16:13-15).

At the beginning of his ministry, Jesus challenged his future disciples to follow him (Mk. 1:17, 19; Jn. 1:43) and to see for themselves (Jn. 1:39, 46). Jesus’s teaching was connected to real-life situations, one way oral people learn best (Bird & Dale 2022, 275; Ong 2002, 42–43). He did not merely preach servanthood; he demonstrated it by humbly washing his disciples’ feet (Jn. 13:4-5). “Oral learners favor learning in real-life contexts and can, in fact, learn abstract principles through this means” (Bird & Dale 2022, 284).

Jesus’s teaching can be described as performance-based pedagogy (Bird & Dale 2022). This instruction puts more value on execution than knowledge (274). An example is his end-time speech, where Jesus clearly favors those who do what is right to those who acknowledge his lordship with their lips only (Mt. 25:34-46). Jesus wants his followers to be doers of God’s will (Mt. 7:21). Before his disciples fully grasped the entirety of Jesus’s mission, he sent them out to proclaim the arrival of God’s Kingdom. Initially, Jesus sent twelve (Lk. 9:1-6), then 72 disciples to nearby areas (Lk. 10:1-12). When they returned, Jesus debriefed them and connected their experiences with additional lessons (Lk. 10:17-20).

Spreading the Word as it was Taught (Missiological Lens)

As seminaries largely remain uncontextualized (Lingenfelter 2001, 449–450), pastors and ministers keep using Western materials that are, at best, translated into local languages to disciple new believers (Song 2006). Sunquist (2017) contends that the principal duty of theological contextualization lies with the indigenous converts themselves (258). However, this is a tall order if they have been accustomed to Western theology (de Mesa 2016, Chapter Experiencing God through the culture, paras. 1–2).

What holds true for education also extends to evangelism. I have been involved in campus ministry for over a decade and have collaborated with various ministries in the Philippines. The most commonly used evangelism strategies are based on Western materials like the Four Spiritual Laws, Evangelism Explosion, or variations of these methods. As Filipinos tend to make decisions without having fully understood and thought through them (cf. Acoba & Asian Theological Seminary 2005, 5–6), a more obedience-oriented approach to evangelism seems more intuitive to me in this context, as a “sinners prayer” is not a good indicator of true repentance.

Knowledge and being should not be separated (Miller 2023). Differentiating between them can be attributed to the Enlightenment. Our primary focus on teaching knowledge “has unnecessarily fragmented generations” (Johnson-Miller & Espinoza 2018, 157). Christian education must refocus on heart transformation over intellectual information: “The whole person is generally overlooked in catechesis and other forms of formal Christian education in the church” (166).

Having interacted with numerous Philippine sending agencies, I see a close resemblance to their Western counterparts. Western missionaries often go as highly trained and well-funded experts, and that pattern can be replicated only by rich Filipino churches. Most Filipinos abroad are overseas Filipino workers (OFW) employed as household helpers, cooks, seafarers, or construction workers, creating vast opportunities for bottom-up missions (Sunquist 2017, 65). Western missiology does not have all the answers to this approach, leaving Filipino churches the chance to find their own theology of missions instead of relying on Western methods. Bottom-up missions is also exemplified by Jesus, who proclaimed that he came to serve (Mk. 10:45).

Relating Pedagogies to Jesus’s Way of Teaching (Educational Lens)

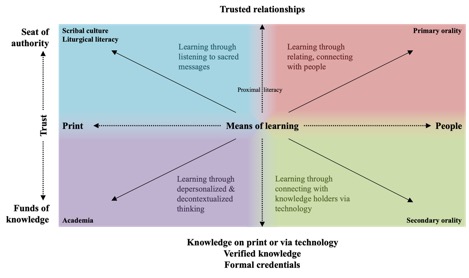

What are some pedagogical approaches suitable for oral learners? The social aspect of teaching is of primary importance in the Philippines. Learning cannot be divorced from its social environment (Gibbons 2020, 2803), as many researchers have confirmed (Lave 2009, 202). Saiyasak (2023) demonstrates that relationships are the key to effective teaching in Southeast Asia (4-7), where “Christian teachers must build relationships with students before they can teach effectively” (Lingenfelter & Lingenfelter 2003, 42). According to Thigpen’s (2020) “Learning Quadrants,” as depicted in Figure 1, oral learners trust in people rather than in printed text (124). For oral people, print text reflects only the author, but communal knowledge is backed by many trusted people (Lingenfelter & Lingenfelter 2003, 38). Jesus had a close relationship with his disciples as they followed him (Mk. 1:17, 19, Jn. 1:43) and observed his ministry (Jn. 1:39, 46).

Figure 1: Learning Quadrants adapted from Thigpem (2020, 124)

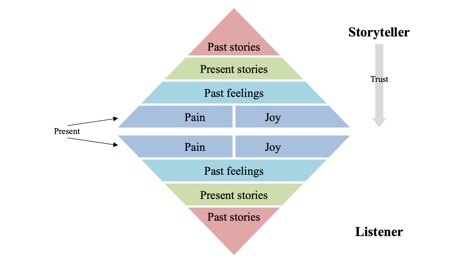

Newbigin (1992) points to the Enlightenment as the reason for “the shift from a way of seeing truth as located in narrative, to a way of seeing truth as located in timeless, law-like statements” (6). Still, stories are at the core of worldview formation and transformation (Storr 2021, 51; Wesch 2018, 320–332). Stories cause us to shed hormones that can make us emotionally more receptive (Phillips 2017). Savage (1996) introduced the “Story Listening Pyramid”, showing that through stories listener and storyteller connect emotionally, as shown in Figure 2. Stories connect the narrator with the audience on a brain-to-brain level (Silbert et al. 2014). The relationship between the storyteller and the listener is vital for accepting the message (Mburu 2019, 108).

Figure 2: Story Listening Pyramid adapted from Madinger (2022, 84)

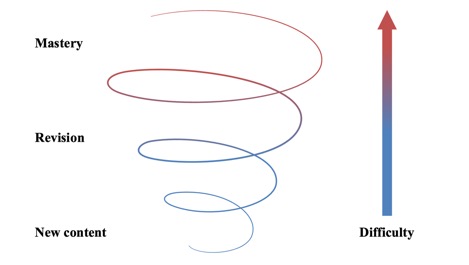

It was Bruner (1960) who suggested that students revisit the same topic year after year, building on the previous knowledge, calling it the “Spiral Curriculum” (13), as seen in Figure 3 below. This way of thinking suits oral learners as they start from the general, narrowing it down to the specific (Shaw 2021, 50) or from the known to the unknown (Mburu 2019, 7), from the “whole to part” (Steffen 2009, 109). Spiral thinkers are inclined to share seemingly unrelated stories that collectively illustrate a central point from various perspectives as they tend to use a more supple communication style by which they prepare the listener to accept the point, often without even mentioning the point directly (Maggay 2023).

Figure 3: Spiral Curriculum (Brunner 1960)

Collaborative learning focuses on groups and must be connected to “real-world problems” (Crumly 2014, 29) and situational (Ong 2002, 48–56). Hofstede’s (2010) data shows that Filipinos tend to be collectivistic, while most Western countries tend to be strongly individualist (97). Learning in groups is more effective as people learn faster, remember better, and can help each other’s understanding (Watson & Watson 2014, 188–210). The mix of real-world and theoretical learning, often in groups, is known as experiential learning, recognized as a very effective way to learn (Johnson 2017, 47).

Wenger (2009) coined the term communities of practice to describe groups of individuals who come together, intentionally or unintentionally, to collaboratively learn and solve real-world problems within a shared field of human activity. Most Filipinos are literate, but they prefer to learn through oral communication. Craftsmen, for example, have told me they obtained their skill “on the job,” not in formal settings. Active learning involves hands-on learning, providing immediate feedback to learners, fostering critical thinking, and encouraging the application of higher-order thinking skills to analyze, synthesize, solve problems, and evaluate outcomes (Crumly 2014, 29).

Case-based learning usually starts with a story or a case (Crumly 2014, 30–31). Jesus often used this approach for deep interactions. For example, it was after telling the Parable of the Sower (Mt. 13:1-9) that he elaborated on its meaning (Mt. 13:18-23). Combining experiential learning with case-based learning can be more effective because the story at the beginning of a learning session is replaced by a real-life experience. Going even a step further, we can look at embodied cognition. The theory states that learning, physical experiences, and emotions are interconnected (Adams 2021). All these different pedagogies can be seen in Jesus’s teaching.

Using Oral Pedagogies to Transform Seminary Education

Can we implement oral pedagogies as used by Jesus in Philippine seminaries, given that students are used to the Western system and are expected to adjust to the teacher (Crabtree & Sapp 2004, 107)? Rather than offering specific recommendations, I will share my ongoing changes with my students, focusing on fostering transformative learning beyond mere information acquisition.

Because English is often seen as superior, I try to elevate the significance of heart-language communication. In class, I predominantly use Tagalog with some commonly used English terms. Additionally, students can engage in classroom discussions and do their assignments in Ilonggo or Cebuano. To reduce the need for reading assignments, I often incorporate videos, songs, illustrations, stories, and even games into my teaching. Moreover, I encourage my students to submit their assignments in their preferred formats: visual arts, mind maps, videos, or voice recordings. Physical movement and other visual forms of expression are encouraged in my class because these have proven to reduce students’ cognitive load while improving learning simultaneously (Ferreira 2021). Whenever possible, I use stories to illustrate a point and as the primary teaching point. I have transformed my syllabi from lists of abstract concepts to narratives, creating an engaging student experience. During the first day of class, we enjoy reading the syllabus together, as different students are assigned to various characters in the story.

Filipinos do not want to stand out from a group even for their academic achievements (Lingenfelter 2001, 455). Learning should not be competitive but collaborative. In the course Community Development, my students collaboratively start and maintain an organic vegetable garden, graded not by the produce quantity but by their collaboration and teamwork.

Relational learning is essential. Chatting about personal and impersonal issues before and in class is a way of connecting (Crabtree & Sapp 2004, 116). In my Anthropology class, we start with a movie night featuring Smallfoot. Later in the course, we analyze the film, as it offers valuable insights into culture and worldview. We enjoy it as we bond and engage in this story, making learning fun and memorable.

Rather than grading exams, my students face post-class challenges related to the topic. For instance, after studying culture shock, they document themselves engaging in an activity unusual for their culture for a week, like sitting on the floor and placing their plate on the chair at mealtimes. This experiential learning is more memorable than memorizing definitions for exams. Many challenging tasks are performed as groups and submitted as multimedia into a group chat. Students still need to research, but we all enjoy their vlogging as, for example, the students picture themselves in the ancient cities of the Roman Empire and conduct interviews with attendees of Paul’s sermons. Students are encouraged to watch each other’s submissions and comment on them to learn from each other.

Do you know how learning a new language in a foreign country feels? Try to memorize to say and write the Great Commission in Japanese. Theory cannot replace the experience of struggling to accomplish something in praxis. For the course Campus Ministry, we follow a dynamic approach. First, we invite representatives from three campus ministries to share their strategies. Afterward, my students collaborate to devise a plan for implementing campus ministry on a nearby campus. Learning takes a hands-on approach in the latter half of the course as students actively engage in campus ministry rather than studying within the classroom.

In the subject Partnership Development, we collectively select a one-week evangelistic outreach project the class will undertake. Following my instruction on connecting with partners, newsletter writing, and presentation skills, the students are tasked as groups with preparing newsletters and delivering presentations in churches to secure funding for the implementation of our outreach project. Nothing I can theoretically teach in class could prepare my students better than their experience.

Conclusion

Examining the seminary environment in the Philippines through cultural, biblical, missiological, and pedagogical lenses has been instrumental in identifying the divergence between my students’ learning preferences, Jesus’s ways of teaching, and conventional Western teaching approaches. Consequently, I have embarked on a transformational journey in my own teaching methodology, striving to align it more closely with the teaching methods of Jesus, as this approach resonates better with how my students learn best. “Christian practices do not require schools or blackboards or textbooks; they are a form of discipleship that fits well with traditional learning strategies of observation and imitation and of learning by doing” (Arrington 2018, 224).

References

Acoba, E. & Asian Theological Seminary, eds. (2005). Doing theology in the Philippines. Asian Theological Seminary; OMF Literature.

Adams, J. D. (2021). More than a feeling: The influence of emotions in learning and implications for church ministry. Christian Education Journal: Research on Educational Ministry, 18(1): 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739891320967017

Arrington, A. (2018). Reimagining Discipleship: The Lisu Life–Rhythm of Shared Christian Practices. International Bulletin of Mission Research, 42(3): 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396939317750550

Bausch, W. J. (1991). Storytelling: Imagination and faith. Twenty-third Publications. https://archive.org/details/storytellingimag00unse

Bilbao, P. P., Corpuz, B. B., & Dayagbil, F. T. (2015). Curriculum development for teachers. Lorimar Publishing, Inc.

Bird, C. H. & Dale, M. (2022). Education and discipling in a performance-based or rote learning context. Missiology: An International Review, 50(3): 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/00918296221103269

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R., eds. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals: Vol. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. David McKay Company.

Box, H. (2014). Don’t throw the book at them: Communication the Christian message to people who don’t read. William Carey Library.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The Process of Education. Harvard University Press. http://edci770.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/45494576/Bruner_Processes_of_Education.pdf

Corpuz, B. B. & Salandanan, G. G. (2015). Principles of teaching 2 (with TLE). Lorimar Publishing, Inc.

Crabtree, R. D. & Sapp, D. A. (2004). Your culture, my classroom, whose pedagogy? Negotiating effective teaching and learning in Brazil. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1): 105–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315303260826

Crumly, C. L. (2014). Student-centered pedagogies and tactics. In Pedagogies for student-centered learning: Online and on-ground. Fortress Press, 21-42. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9m0skc

de Mesa, J. M. (2016). The faith of Jesus as “pagsasaloob at pangangatawan”: A cultural approach. In P. D. Bazzell & A. Peñamora, eds., Christologies, cultures, and religions: Portraits of Christ in the Philippines. OMF Literature.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The English language and the Word of God. In S. W. Wong & S. Canagarajah, eds., Christian and critical English language educators in dialogue: Pedagogical and ethical dilemmas. Routledge, 154-157.

Ferreira, J. M. (2021). What if we look at the body? An embodied perspective of collaborative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4): 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09607-8

Gaston-Dousel, E. G. (2011). Interfacing theology, culture, and the English language. Education Quarterly, 69(1): 50–71.

https://www.journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/edq/article/view/2904/2678

Gibbons, A. S. (2020). What is instructional strategy? Seeking hidden dimensions. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(6): 2799–2815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09820-2

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind; intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. Rev. and expanded 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill.

Johnson, D. W. (2017). Together: Group Theory and Group Skills. Pearson.

Johnson-Miller, B. C. & Espinoza, B. D. (2018). Catechesis, mystagogy, and pedagogy: Continuing the conversation. Christian Education Journal: Research on Educational Ministry, 15(2): 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739891318761673

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Lave, J. (Ed.). (2009). The practice of learning. In Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists … In their own words. 1st ed. Routledge, 200-208.

Lingenfelter, J. (2001). Training future leaders in our classrooms. Missiology: An International Review, 29(4): 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/009182960102900404

Lingenfelter, J. & Lingenfelter, S. G. (2003). Teaching cross-culturally: An incarnation model for learning and teaching. Baker Academic.

Madinger, C. (2017). Applications of the orality discussion. Evangelical Missions Quarterly, 53(1): 54–59.

_____. (2022). Transformative learning through oral narrative in a participatory communication context: An inquiry into radio drama-based training among Zambian caregivers of exploited children [Doctoral dissertation, University of Kentucky]. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/comm_etds/110

Maggay, M. (2023). Personal communication.

Mburu, E. W. (2019). African hermeneutics. HippoBooks.

Mercado, L. N. (2002). Lakaran: A Filipino way of proclaiming christ. Studia Missionalia, 51: 301–332. https://search.ebscohost.com.oca.rizal.library.remotexs.co/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edscal&AN=edscal.14025747&scope=site

Miller, J. A. (2023). Native knowing, western knowing, and Scripture’s knowing [Paper presentation]. Evangelical Missiological Society, Annual Meeting, Dallas, TX.

Mohammad, N., Ma, H., & Akrim, A. (2023). Examining assessment practices of K-12 public school teachers in Maguindanao province [Preprint]. In Review. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2960913/v1

Newbigin, L. (1992). “The Gospel and our culture: A response to Elaine Graham and Heather Walton. Modern Churchman, 34(2): 1–10. https://newbigindotnet.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/92goc.pdf

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. Routledge.

Phillips, D. (2017). The magical science of storytelling. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nj-hdQMa3uA

Saiyasak, C. (2023). Presenting the gospel message in alignment with the Asian learning mode and style in the context of interpersonal relationships. Asian Missions Advance, 29(4): 1–8. https://www.asiamissions.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/ChansamoneSaiyasak.pdf

Savage, J. (1996). Listening & caring skills: A guide for groups and leaders. Abingdon Press. https://archive.org/details/listeningcarings0000sava

Shaw, P. (2021). Communication, language, and cross-cultural teaching. In R. Kassis & M. A. Ortiz (Eds.), Teaching across cultures: A global Christian perspective. Langham Creative Projects, 47-61.

Silbert, L. J., Honey, C. J., Simony, E., Poeppel, D., & Hasson, U. (2014). Coupled neural systems underlie the production and comprehension of naturalistic narrative speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(43). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323812111

Song, M. (2006). Contextualization and discipleship: Closing the gap between theory and practice. Evangelical Review of Theology, 30(3): 249–264.

Steffen, T. A. (2009). Evangelism lessons learned abroad that have implications at home. Journal of the American Society for Church Growth, 20(1): 107–135. https://place.asburyseminary.edu/jascg/vol20/iss1/8

Storr, W. (2021). The science of storytelling: Why stories make us human and how to tell them better. Abrams Press.

Sunquist, S. (2017). Understanding Christian mission: Participation in suffering and glory. Baker Book House.

Thigpen, L. L. (2020). Connected learning: How adults with limited formal education learn. American Society of Missiology Monograph Book 44. Pickwick Publications.

_____. (2022). Deconstructing oral learning: The latest research. In T. A. Steffen & C. D. Armstrong (Eds.), New and old horizons in the orality movement: Expanding the firm foundations. Pickwick Publications, 15-45.

_____. (2023). How a novel research framework resulted in fruitful evangelism and discovery: Introducing ethnoscopy and spiritual patronage. Great Commission Research Journal, 15(2): 25–43. https://place.asburyseminary.edu/gcrj/vol15/iss2/14/

Watson, D. L. & Watson, P. D. (2014). Contagious disciple-making: Leading others on a journey of discovery. Thomas Nelson.

Wenger, E. (2009). A social theory of learning. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists ... In their own words. 1st ed. Routledge, 209-218.

Wesch, M. (2018). The art of being human: A Textbook for cultural anthropology. New Prairie Press. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/20

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Expanded 2nd ed. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.