A Mathematically Based Model of

Disciple Making Movements

Chris Keener and Dave Foster

Published in Global Missiology, www.globalmissiology.org, January 2025

Abstract

Although many practical resources are available to encourage and facilitate Disciple Making Movements (DMM), a quantitative theoretical framework to undergird the conclusions of authors and practitioners is currently unavailable. Such a model will be useful to assist in increasing the rate at which disciples are able to multiply and could help more slowly reproducing groups of disciples to transition over time into DMM’s. We have developed a model of disciple multiplication that builds from the starting point of an individual disciple maker. This article provides conclusions and applications that are comprehensible to every practitioner, without delving into the underlying mathematics. A key conclusion comprises the twin necessities of investing significant time sowing the gospel among those who are yet far from God and of the mobilization of all (or most) disciples into the harvest (John 4:35). By focusing on disciples’ most controllable factor—prioritization of time on more receptive individuals and on existing close relationships—rates of multiplication can be doubled in most contexts. Furthermore, the model explains how different optimization strategies are needed for different contexts as average receptivity and relational connectedness vary.

Key Words: Disciple Making Movements, disciple multiplication, Discovery Bible Study, mathematical model

Introduction

All over the world this gospel is bearing fruit and growing, just as it has been doing among you since the day you heard it and understood God’s grace in all its truth. (Colossians 1:6)

Multiplication of Jesus’s followers in Disciple Making Movements (DMM) is powerfully impacting global Christianity (Long 2020 & 2023). At the foundation of every DMM are disciples actively leading people who are far from God to become disciples of Jesus, who in turn reproduce more disciples. In order to gain a more thorough understanding of these movements, we have developed a mathematical model to describe the relationship of the micro—individual disciples making more disciples—to the macro—rapid multiplications of streams of disciples across any given region, continent, and even the globe. The model takes into account three factors: each disciple’s relational network, receptivity of hearers to the gospel message, and time spent in gospel-related conversations and Bible study. In this article, we share some of the conclusions of the in-depth analysis of these three factors, details of which can be accessed online (Keener & Foster n.d.) or by contacting us, the authors, via this journal.

The gospel of Jesus is good news. It is proclaimed and received. In the parable of the sower (Mark 4:1-20), Jesus conveys clearly that the proclaimed gospel is received well by some but has little impact on others. Describing this variation quantitatively enables us as gospel messengers to adapt priorities and methodologies as we communicate the message. One message, the gospel, is transmitted, although the way that message is communicated is influenced by the messenger’s own background and relationship with Jesus. But what is received can be garbled by noise, suppressed by inattentiveness, distorted by misunderstanding, or outright rejected.

For the sake of God’s glory, practitioners in Disciple Making Movements are seeking to maximize both the number of new followers of Jesus and their depth of relationship with the Lord. Because we the authors are using math as our tool, this article focuses on the quantitative aspect of DMM. However, this use of math does not equate people to numbers. Fundamentally, every disciple must rely upon the leading of the Holy Spirit, who empowers Jesus’ followers for the purpose of witness (Acts 1:8). A DMM leader writes, “Disciple Making Movements are not a program, not a strategy or a curriculum. It is simply a movement of God. Without Him, there is nothing” (Sunshine et al. 2018). Jesus Himself makes clear that his disciples are absolutely dependent upon him (John 15:5), including dependent upon him to be his witnesses, as he commanded. Mathematical modeling is useful for general principles, but each specific movement and every human being is uniquely constructed by God. A model cannot solve every problem and certainly cannot replace the many valuable case studies and other research in missions literature (see, for example, Farrah 2021 and Larsen 2018).

Though theoretical, this model does have immediate practical implications. For example, we the authors are able to answer questions that have nagged us for decades, such as: If a practitioner considers two options to spend an equal amount of time and effort— 1) purely scattering the seed of the Gospel, and 2) spending more time developing a small group of people from nonbelievers into faithful followers of Jesus—which option will lead to more people ultimately coming into a deep relationship with Christ marked by a life of obedience and love? As we shall see, Option 2 will be far more effective, regardless of the practitioner’s context. Although many applications of our model have already been naturally discovered by leaders, some Christian groups who are struggling to multiply may benefit by considering the sound logical reasoning that is available in a mathematical model.

The rate at which a group of disciples doubles depends on several factors. Using the common experience of disciple-making practitioners, we start from the assumption that the likelihood of a nonbeliever becoming a follower of Jesus depends on these three factors: 1) Among people who do not know God, receptivity to the gospel varies. 2) The more a person is exposed to gospel-related conversations and participates in Bible-related discussions, the more likely that person is to become a follower of Jesus. 3) A person is more likely to receive the gospel if the message comes from someone they know personally than if they hear from a stranger. In summary, making a disciple depends on the receptivity of the hearer, closeness of relationship between disciple and hearer, and amount of time spent talking about the gospel, God, and the Bible. For DMM to occur, new followers of Jesus must make disciples, following the example of the people who invested in them. From these three assumptions, we will discover many practical implications for disciple-makers.

Significantly, different strategies are appropriate for each different scenario. In most cases, optimizing the approach to the context can result in a movement multiplying up to twice as fast. For example, where receptivity is low, practitioners can be most effective by searching for the few people with higher receptivity. And where interpersonal relationships are slow-forming and few, followers of Jesus will want to capitalize as much as possible on their existing close relationships. Relevant to this conclusion, practitioners of one context should be sensitive to those in different contexts and understanding that, while others’ tools may not be fully applicable in one’s own setting, the same tools could be quite useful in another setting.

Ingredients of the Model

Elements in the Rate of Multiplication: Sender Component

Even in the best case where the hearer of the gospel message is potentially completely receptive, if no disciple ever shares the gospel with that person, he or she will not become a follower of Jesus. Believers must share the good news as Jesus commanded, and Jesus declares that this command applies to anyone who is called his disciple (Mark 8:34-38). Equally vital is reliance upon the Holy Spirit Jesus gave for the purpose of witness (Acts 1:8). Further, a disciple’s own personal relationship with Jesus influences and grounds his or her witness, and the Lord has uniquely placed each disciple in trusting relationships that facilitate this witness. One of the stated goals of DMM is that all disciples are equipped to penetrate their spheres with the gospel message (see, e.g., Smith & Kai 2011; Lim 2021).

Certain elements are essential in the “Gospel about Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Mark 1:1). A study of the gospel summaries in the book of Acts and other key Scripture passages shows that God created the world (Acts 17:24-26) and that everyone is bound in sin before they receive the gospel (Acts 17:30; see also John 3:18, Rom 11:32, Eph 2:13). In love, God sent Jesus into the world to sacrifice himself on the Cross as payment for human sin (John 3:16, Rom 3:25), and Jesus has risen from death to life as the living and glorified eternal Savior of all who receive him (I Cor 15:3-8, Acts 2:24-36). Therefore, all are called to repent and believe in the living Savior, upon which they receive forgiveness of their sins and the promised Holy Spirit, who is present in all followers of Jesus (Acts 2:38-39). These acts of God, corresponding invitation, and promise to people are what we the authors mean by the gospel. Also, it is generally fruitful to supplement this message with other narratives and teaching from both the Old and New Testaments.

Receiver Component

In reality, the response of unbelievers depends on many factors, such as the hearer’s relationship to the disciple, the amount of time the sharer spends with the seeker discussing the Word of God, prior exposure to the gospel (or exposure to hypocrisy, a negative influence), the receiver’s pride, hardship in his or her life, neighborhood, cultural predispositions toward or against Jesus, and financial income level. The likelihood of a hearer of the gospel becoming a disciple is specific to each hearer.

Receptivity is an aggregate of factors, many of which are also very important in themselves, such as life circumstances and personal disposition to the gospel. Although receptivity is largely a given, some aspects of receptivity may be influenced by a group of practitioners. Addressing poverty and genuine needs in a community is an integral part of DMM strategy in many cases (Kebreab 2021; John & Coles 2021: “Community Learning Centers”; Larsen 2018; Johnson 2017), with the goal of enhancing receptivity. This approach (often termed “access ministry”) is a dimension of obedience for disciples (see, for example, Luke 16), in addition to sharing the gospel. In many cases, miraculous healings improve receptivity (Luke 10:9 and its continued application). Believers working with integrity to serve the Lord in their “secular” jobs may also improve receptivity. Of course, in terms of spiritual dynamics that support higher receptivity, prayer in faith-filled reliance upon the Lord is critical (Garrison 2004).

Practitioners often describe a process over time in which a person who is far from God comes to know Jesus. Jesus described a teacher of the Law in terms that could be interpreted similarly (Mark 12:34), “not far from the Kingdom of God,” even though he defines only two states at Judgment Day (e.g., Matt 25). One of the most important factors is the amount of time that a hearer of the gospel spends in direct biblical or gospel-related discussion with one or more disciples of Jesus. This time refers to two-way interpersonal interaction with individuals or in small groups (in contrast to listening to sermons, which may also be valuable but is not considered here). The vital nature of this time is evident when considering the enormous fruitfulness of the Discovery Bible Study (DBS) approach around the world (Farrah 2021, chapters 1,2,3,7,10,12,13,16; Larsen 2018). Given sufficient time reading and discussing the Bible and how it applies to someone’s life, the probability of becoming a follower of Jesus can be very high, albeit requiring patience.

This time factor is understandable. It takes time for the gospel to sink in. Why, for example, is sacrifice necessary? Understanding the Law of Moses needs to develop. What is repentance in practice, or what should loving one’s neighbors actually look like? What is the clear distinction between light and darkness that makes the transmission of the gospel absolutely necessary? What does it mean practically for Jesus to be Lord? Many truths must be heard and demonstrated repeatedly to become clear to those who have no prior knowledge. And without clarity of understanding, it is difficult for seekers to hand over control of their entire lives to God. Patience is necessary as a seeker discovers truth about God and human sinfulness—even as God had been patient with disciple makers when they were still living without faith in Jesus.

Relational Connection

In many contexts, sharing the gospel through a relational network is much more effective than sharing with strangers (Shull 2021). Generally, trust and influence form over a period of time in relationships. Thus relational influence tends to increase with time spent together, although it also depends on personal preference and the positions of the disciple and the hearer within a group or relational network.

In some contexts, forming intimate relationships takes a long time, and each individual tends to have fewer close relationships. The time to form relationships can be significantly longer than the time needed to disciple someone. In this situation, sharing the gospel within a relational network has far more impact than the same amount of sharing with strangers, for whom it is difficult to quickly penetrate the hearer’s defenses.

It is important to note that a new believer has already invested significant time in developing relationships before believing in the gospel and beginning to share with others. It is well known that new believers are often the most effective witnesses for Christ (Hayward 2002, 225-226). A new disciple already has close relationships and can find those with high receptivity among them, so that less time is necessary to lead a few others into relationship with Jesus. Likewise, Discovery Bible Studies are most effective when they gather people from pre-existing social relationships, rather than bringing together people who do not already know each other.

How the gospel is conveyed contributes to the credibility of the disciple with the people being reached. For example, rural areas with more homogeneous cultures may resonate with a particular method of evangelism and discipleship, whereas cities with more diversity will likely not exhibit a high response to any one method but will require more complex and varied approaches from practitioners. The ability to communicate effectively improves over the time the outsider spends in a community, and those who grew up in a particular environment are generally better equipped to convey the gospel than the outsiders. Thus the outsider needs to be a good listener and quickly entrust gospel communication to new disciples.

Finally, although time spent focused on the Bible is more influential on disciple-making than other time spent with an individual, this time contributes to the total amount of time spent together thereby tending to enhance relational influence. The impact of DBS is enhanced by the strength of relationships formed through discussions focused on the Bible and its application to life.

Application to Various Contexts

Disciple Making in Various Contexts

Our discussion will now consider the cumulative impact of all the gospel sharing a believer does. Although disciples should not expect someone to believe every time they share the gospel, the impact of persistence adds up. Furthermore, efforts to share the gospel with certain individuals are more likely to pay off.

Potentially, a few receptive individuals may respond to the gospel quickly and thus strongly influence a disciple’s reproduction rate. David Garrison’s seminal booklet Church Planting Movements (Garrison 1999) employed the analogy of nets—broadcasting the gospel to many people—and filters—finding those with high responsiveness to the message. Effective practitioners share the gospel with many people, but they also filter by investing more time with those who respond positively to the initial declaration of the gospel. They realize that receptivity of any individual hearer is largely beyond their control but in the hands of the Lord, although they may collectively, gradually enhance average receptivity as their loving behavior contributes to a positive reputation of believers and Jesus in a community. On the other hand, after finding a responsive person, allocation of time is under the control of the disciple-maker. If Jesus only could do what he saw the Father doing (John 5:19), surely we who are his disciples must follow his example in all areas of life, including disciple making. By following the lead of the Holy Spirit to the people God is already working with, disciple-makers are able to multiply a little faster by investing time in them—especially if they find high receptivity in those who are already in closest relationship with them. In this way, they reap a harvest where God has been sowing. Likewise, for the same reason, trainers are wise to invest time in those who implement the training.

Returning to Relational Connection

Another example involves a U.S. urban context. Typically, ministry there that is focused on oikos (one’s closest relationships) is more effective than solely seed-sowing among strangers (Shull 2021). Although sharing with oikos is important in all contexts, it appears to be more crucial in cities in Europe and the U.S. In this case, close interpersonal relationships are a scarce resource. By focusing time on those few available closest individuals, the disciple’s rate of multiplying increases. This effect is further enhanced by the fact that a close friend or relative is more likely than a stranger to be willing to spend time in a DBS.

On the other hand, spending equal time developing all relationships in order to “earn the right” to share the Gospel is ineffective. First, doing so would be faulty worldly reasoning that is inconsistent with Jesus’s statement that all authority in heaven and on earth belongs to him (Matthew 28:18). With complete authority, he commanded his disciples to continue teaching obedience to all his commands (Matthew 28:19-20), in the power of God, the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:8, John 20:21-23)—himself being with us (Matthew 28:20). Surely, he granted authority to his disciples to obey him by proclaiming the gospel, and this authority is distinct from knowing that the gospel will be accepted. The proclamation should be done respectfully, but it can be done at an early phase of a relationship before relational closeness has grown. Second, it often takes a big investment of time to improve relational closeness with a few individuals, only to discover that most of them are not receptive to the Gospel (Smith & Kai 2011, 206). The best way to gauge receptivity is to observe the response to a presentation of the gospel or at least spiritual truths that prepare for understanding the gospel. Because of the time investment and lack of knowing an individual’s receptivity, the result of delaying gospel presentation is disappointment and demotivation for the believer. It is more advantageous for the believer to self-identify as a follower of Jesus, and openly share at least some spiritual truths, from early in the relationship. If certain individuals respond negatively, those with low receptivity may self-select to keep a high relational distance from the believer, who can then invest more time intentionally in those who are interested. Because receptivity varies significantly among individuals, the rate of making disciples improves greatly when the practitioner filters for high receptivity prior to intense investment of time in new relationships, of course relying on the Holy Spirit for guidance to responsive people (John 6:44).

Prior exposure to the gospel often functions to shorten the time to make disciples. Effectively, time that a nonbeliever spends hearing the gospel and other biblical truth accumulates regardless of which believer is the source. A quick harvest frequently reflects prior exposure to the gospel and the word of God. Thus Jesus’s observation that “one sows and another reaps” (John 4:37) applies to multiple contacts with believers as well as in the statement’s original context. (Jesus was referring to increased receptivity where the Samaritan people group had been influenced by God’s word preparing them for centuries.) Similarly, a believing community collectively has high leverage on multiplication. In the context of community, especially (but not limited to) a group DBS, the seeker is exposed to biblical discussion with multiple individuals, each contributing different perspectives that complement one another. The group effectively multiplies the amount of time hearing biblical truth and greatly enhances the rate of disciple making. Furthermore, the mutual responsibility to share the truth with others that is fostered in a group that practices healthy accountability is extremely important. Without this accountability, and just left to individuals, the degree of gospel and truth sharing will be much less.

Adjusting the Filter to Become More Efficient and Productive in Disciple-Making

When we believers get stuck and find it difficult to make disciples, often we have to adjust our net to cast more widely or adjust our filter one way or the other to spend our time more wisely. These adjustments are critical for launching a movement in any particular context. In our model for this article, we have considered a disciple’s multiplication rate for two different kinds of context, described in Table 1. Population A has a low average receptivity and less prolific formation of close relationships, so that launching a DMM is more challenging in this context. Population B has higher average receptivity and higher prevalence of close relationships. In Population A, there are relatively few close relationships, and in Population B, typically people have many close relationships as well as more distant acquaintances. It turns out that a disciple’s optimum prioritization of time in these two contexts is substantially different.

Assuming that a disciple has a certain number of hours per week available for gospel-related discussions, the amount of time spent with various hearers of the gospel has to be prioritized. For Population A, the optimum priorities involve exceptional patience with those closest in relationship to the practitioner—doing everything possible that might lead to a DBS with them. The more distant the relationship, the more selective the practitioner will be, until with strangers the goal is to find those with exceptionally high receptivity. For Population B, in order to achieve the optimum rate of multiplication, the practitioner must be more selective and only extensively disciple those with highest receptivity and reasonably close relationship.

|

Receptivity |

Relational Connectedness |

|

|

Population A |

Low receptivity |

Less relational |

|

Population B |

High receptivity |

More relational |

Table 1. Description of two distinct populations, A and B

The Critical Importance of Disciple-Makers’ Commitment and Availability

One critical conclusion of our study is that DMM requires a great deal of hard work on the part of every disciple. If the average disciple puts only one hour per week into disciple-making, the disciple reproduction rate for Population A is probably not going to be able to keep up with attrition and population growth. Likewise, if a congregation relies on paid staff to do this work, growth will not result. For example, if one person for every 50 believers is a full-time professional disciple-maker, that person could potentially spend more time than the average disciple-maker, with a contribution equivalent to perhaps 3-4 unpaid workers. Nevertheless, without contribution from lay people, the rate would probably be too low to achieve any significant growth. Reliance upon a core team of active believers does not achieve multiplication, either. Pray for more laborers.

It is important to note that disciple multiplication must prioritize time focused explicitly on making disciples, although this time may be either planned or spontaneous sharing during normal life activities. As essential as they are, other priorities such as laying the groundwork with community service, discussions about church, or conversations about peripherally related spiritual topics cannot by themselves result in more disciples.

The Critical Importance of Disciple-Makers Prioritizing Their Valuable Time

Common to both populations described above is how time prioritization results in significantly faster reproduction. Without any filtering, i.e., spending equal small amounts of time explaining the gospel to anyone without regard to their receptivity, cuts the multiplication rate in half, regardless of the context. Listening well and accurately assessing the response to spiritual conversations is extremely important.

Another general conclusion is that the outsider, who initially has no close relationships, can achieve reasonable results by filtering more tightly on receptivity. Thus by filtering to the top 5% of receptive individuals, the outsider can reap a significantly greater harvest than by purely random engagement. The resulting multiplication rate increases by 80% for Population A as a result of this filtering, and by 30% for Population B. This strong filtering on receptivity describes what practitioners call a “Person of Peace” (POP) search (perhaps more biblically accurately described as a Fourth Soil Person search), and this approach is relevant to both populations. An insider may choose to practice a POP search as a means of gaining experience sharing the gospel in an environment of strangers—thus lowering the risk of offending close relations. However, for an outsider, a POP search is the best available approach.

A final general conclusion is that the optimum fraction of time spent in DBS or other long-term spiritual discussions is around 80%. If a practitioner spends ten hours/week actively sharing, about eight hours of that time will be in Bible study, after an initial period of searching for receptive individuals.

A Closer Look at the More Prolific Population B

There are significant practical implications for the differences between Population A and Population B. For Population B, the response rate is so high that the optimum can only be achieved by filtering on both receptivity and relational connectedness. Practitioners will find the best results by seeking above-average receptivity among close relatives and friends, which may be 30-50 people, due to the highly social nature of the culture. Among these close relationships, practitioners will find enough responsive and connected people to form DBS groups that will eventually develop into churches.

In the environment of Population B, if believers share with everyone without regard to receptivity and depth of personal relationship, their time is used up largely with people who ultimately will not become followers of Jesus. Practitioners can quickly spread themselves too thin. This lack of “intentionality” slows DMM growth. Even so, any diligent effort to make disciples will be rewarded with a multiplying movement, as long as most believers are actively spending time sharing their faith.

Strategies to Improve Reproduction Rates for Population A

For Population A, on the other hand, the practitioner cannot afford to filter heavily on either receptivity or relational connectedness. In order to focus on close relationships, it is not possible to filter strictly on receptivity. However, below a certain level of receptivity, hearers will not be interested to spend time with the practitioner discussing spiritual things (i.e., they self-filter). Therefore, the practitioner must expand beyond the closest relationships, such as family members, to include neighbors, friends, and colleagues, probing a larger number of people for their spiritual interest, until finding those who are interested in ongoing gospel-related dialogue.

For Population A, only with extensive time spent discipling a few people can the practitioner compensate for the scarcity of relationships and receptivity. And because discipling people into the Kingdom takes a longer period of time, it is beneficial to be continuously probing those who move in and out of one’s relational networks, searching for receptive individuals. For some individuals, receptivity can increase during a time of crisis, and offering to pray for anyone who shares difficulties in life can be an avenue to simultaneously show love and probe for spiritual interest. Creative solutions, such as lighter discussions than DBS, and Stories of Hope (for example, see Sundell 2016), may enable increased time in spiritual discussions among those who are not prepared to commit to a DBS—perhaps leading to a DBS later. One approach is to have open discussions where the seeker is free to raise doubts and objections and has equal input with the believer to guide the topic of conversation—informally or formally. Optimally, by facilitating DBS with several people during the same period of time, the practitioner can have several individuals at various stages in the process of becoming disciples, potentially seeing new baptisms on a somewhat regular basis. For Population A, in the best case a new baptism would be, on average, every two years for each dedicated practitioner. If every follower of Jesus in this context is diligent, this process will lead to DMM, even though individual practitioners may feel that the growth is slow.

For Population A, there is no room to burn bridges in relationships. The parable of the Lost Sheep is especially relevant here. Rapid filtering is inappropriate to this context; because receptivity is not easily measured, disciple-makers need time to assess spiritual receptivity with wisdom from the Holy Spirit. Filtering on receptivity should be based on attitudes such as flagrant, persistent rejection of the gospel, consistent lack of interest, and deliberate choice to sin. Those who pursue relationship with disciples, knowing they are believers, and anyone who is sincerely seeking spiritual truth should be considered to have high receptivity. To maximize the disciple-maker’s controllable portion of building closer relationships, it is important to be a good listener and learn to communicate compassion (Keener 2021). Each community of believers needs to be united around the gospel, never divided. A loving community is attractive and increases receptivity. And bodies of believers will do well to serve the surrounding community in ways that may enhance receptivity. On the other hand, they have to reserve sufficient time to have gospel-centered conversations, and especially DBS whenever the opportunity arises, because serving a community without sufficiently sharing the gospel results in a low number of gospel shares and cannot possibly lead to disciple-making.

Church leaders who serve Population A need to set an expectation that most hearers of the gospel will need extended experience in biblically-related discussions before they commit to follow Jesus and to be baptized, and some will need continued discipleship for a long time before they can reproduce. New disciples may need time to develop a relational network through which the gospel can travel; rebuilding damaged relationships through forgiveness and humble reconciliation will be fruitful. They may need to learn how to love their neighbors in order to have more meaningful and peaceful conversations. In some cases, they need the power of the Holy Spirit to break their addictions. The work of making a disciple is not complete until he or she is making more disciples apart from outside help.

Mature followers of Jesus must be patient and persevere even when they seem to lack fruit for several years. They have to be reminded not to give up spending time among the lost, in obedience to Christ, out of love for him and the lost, not demanding the reward of seeing frequent positive results. A team of believers should celebrate together whenever a new soul is welcomed into the Kingdom of God anywhere in the network. The reward of disciples’ labor is in heaven, along with a closer walk with Jesus on earth through obedience and reliance upon him. Amidst Population B, persecution is often the norm. But with Population A, perseverance may be just as difficult. The believer needs to pray and commit to continue to do good (I Peter 4:19).

Alternatively, a believer living among Population A may sometimes seek out pockets of higher responsiveness—for example, among specific ethnic neighborhoods, or poor neighborhoods. This approach can be particularly helpful to encourage believers who have become discouraged by long periods without results. And some of the new believers emerging from minorities eventually may be encouraged to disciple the majority population. Long-term strategies for young believers to develop career paths in positions of societal influence will be helpful. Nevertheless, less responsive communities currently need a gospel witness. Perseverance has paid off historically. For example, investment of missions resources among Muslim peoples in the 1980’s and 90’s have resulted in a harvest in the last two decades (Garrison 2014). As Jesus said, “One sows and another reaps.” We must faithfully persevere in the hard places.

Strategies in Cities

In most large cities, the population is very diverse. Thus a single approach to evangelism or engaging in spiritual conversations will not be effective with everyone. In order to enhance the probability of positive reception, the believer needs to listen carefully to each person, not only to gauge the level of receptivity but also to understand that individual’s worldview. By personalizing a response to that individual, gospel-related communication will be clearer, and Jesus’s love is more likely to be perceived. Asking probing questions and showing genuine interest in the answers, as well as making effort to share in others’ interests, is very useful (Pollock 2010, Chapter 6 (65-74) and Chapter 11 (108-113)). Long-time followers of Jesus can remain challenged for many years learning about other worldviews and practicing good listening skills. New believers need encouragement to share fearlessly, so that they can bear fruit immediately and also begin learning. A related principle is expressed by one movement leader, “Keep doing what you’re doing, and you’ll get better at it” (Wood 2021). No one ever fully masters disciple-making; we are all equally learners, sitting at Jesus’s feet.

Further scenarios, Populations C and D

Consider two other groups, described in Table 2: Population C with low average receptivity (like Population A) but where it is relatively easy to form relationships (like Population B), and Population D with high receptivity but where it is difficult to form relationships (receptivity like Population B and relationships like Population A).

|

Receptivity |

Relational Connectedness |

|

|

Population C |

Low receptivity |

More relational |

|

Population D |

High receptivity |

Less relational |

Table 2. Description of populations C and D

Population C resembles much of the Muslim world in the 1980’s, when a new agency advertised with the slogan, “Missionaries to Muslims: Literally 1 in a Million.” After concerted effort, albeit only achieving 1 in 500,000 recently, God moved in ways far beyond human control, so that receptivity has increased in the twenty-first century (Garrison 2014). More than 30 years of prayer and sowing seems to have somewhat softened the soil.

For Population C, the optimum multiplication rate is achieved by filtering strongly to spend time discipling those with the highest receptivity (e.g., top tenth), but without discriminating as much on relationships (selecting roughly the half who are closest to the disciple maker). If such a community is not closed off to outsiders, strangers can function relatively well in this environment. On the other hand, for Population D, which is less relational, the best result occurs where time is focused on the closest relationships to the disciple maker (e.g., top tenth), with relatively loose filtering on receptivity (eliminating only the bottom half or so). Much of the U.S. is probably more nearly described by Population D (less relational but receptive) than by Population A (less relational and poor receptivity). The practitioner in this setting may want to initiate DBS starting with his or her closest relationships and working outward to the next closest relationships, until free time is filled up with DBS or similar groups, or DBS with individuals when necessary, in the case that willing participants don’t know one another. In general, the discipler should filter most strongly on the weakest characteristic of a people, whether that is receptivity or relational connectedness.

Summarizing the Reproduction Rates across the Different Contexts

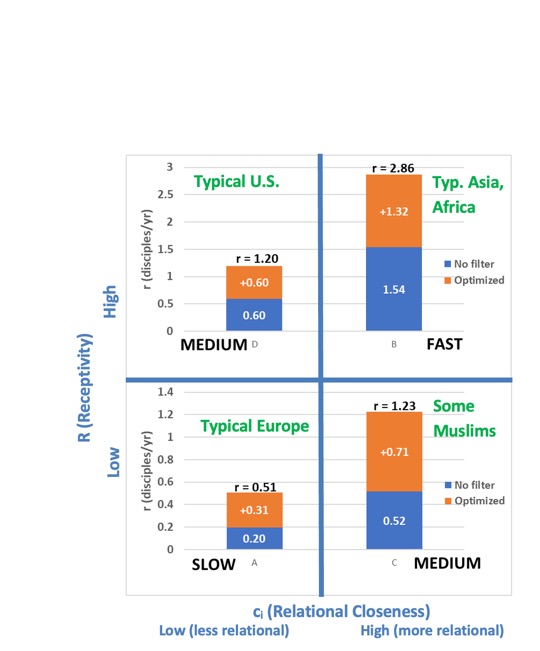

This article has been referring to a rate of disciple reproduction, which is the average number of times in a year that each disciple in a movement makes another disciple. This rate can be less than one. If, for example, it takes two years, on average, to make a disciple, the rate is 0.5. Or the rate can be more than one, e.g., 2 if two disciples are made each year. A rate of 1 means that the number of disciples doubles annually. For a convenient abbreviation, this rate is referred to as “r.” Figure 1 shows one of the outputs from our model, the dependency of r on context. Here, we have assumed that disciples generously contribute 16 hours/week for disciple making, thus these numbers are quantitatively optimistic. We note, however, that the range of r derived from the model with these optimistic assumptions is similar to that observed in actual DMM’s, in which r ranges from 0.2 to 1.7 (Keener & Foster 2025).

In Figure 1, two different rates are described. The blue bar describes the rate that can be achieved through randomly spending a short amount of time sharing the gospel with people indiscriminately, i.e., with no intentional filtering. The full height of the bar (including both blue and orange portions, labeled “r =…”) indicates the rate that can be achieved by optimizing filtering for each context. Optimization means that the disciple maker spends more time in DBS and in-depth spiritual conversations with relatively responsive individuals in already-existing closer interpersonal relationships. The optimum filtering may be based more on receptivity or more on relational closeness, depending on the context. What follows are the practical implications for disciple makers in each of the four contexts.

Populations A-D are labeled at the bottom of each bar in Figure 1. Population A, with low receptivity and weak relational ties, is the most difficult environment in which to launch movements. There, when casting seed broadly enough to find several individuals who are willing to participate in DBS, it should be possible to double a movement every two years (r =0.5), assuming all disciples are engaged with the same intensity. The rate r is directly proportional to the amount of time invested. Given people’s busy work schedules and family responsibilities, devoted disciples may only be able to dedicate about 5 hours weekly to evangelism and DBS (instead of 16 hrs/wk); then, realistically, it might require 6-7 years to double (r =0.16), even if all followers of Jesus are active in disciple-making. Given enough time, a large number of Jesus followers will result even with this lower doubling rate. However, if the disciple maker is merely randomly engaging the lost in brief conversations without filtering, regardless of receptivity or depth of relationship, at 5 hrs/wk, doubling could take over 13 years (r =0.075), or much longer when considering attrition, which is significant in this case. If only a fraction of disciples is engaged in reproducing, it is not difficult to imagine a decline in the number of Jesus’ followers over time.

In the other contexts (Populations B, C, D), rates are much higher. Movement is possible even without DBS, although the depth of discipleship would be lacking. In every case, attention to filtering approximately doubles the rate (from the length of the blue bar to the full length of the bar including both blue and orange portions).

Figure 1. Summary of disciple reproduction doubling rates (r) by population and filtering. Populations A-D are labeled at the bottom of each bar. Blue bars are the rate that is achieved without any intentional filtering. The full height of the bar, labeled “r=…”, is the rate that can be achieved with optimum filtering. Green text is the authors’ best estimate of environments that approximate the four populations.

Table 3 summarizes the applications of this model to the four contexts. Each context requires different means to achieve the optimum rate of growth. Although expert practitioners with years of experience will intuitively arrive at these conclusions, often with more nuance, these guidelines may be helpful for the majority who need some direction or desire to see more results in their specific context.

|

Population |

Receptivity |

Relational |

How to Optimize |

|

A |

Low |

Less |

· Probe relational network periodically for those who are willing to enter DBS. · Work outward from closest relationships. · Create low-commitment entry points into Gospel conversations. · Listen well and show genuine interest. |

|

B |

High |

More |

· Focus time selectively on friends and relatives with above-average receptivity. · Focus on groups, not individuals. |

|

C |

Low |

More |

· Focus time on those with highest receptivity. · Focus on groups, not individuals. · Respect authority of community leaders. |

|

D |

High |

Less |

· Focus time on closest relationships, and work outward as necessary. · May need to start DBS with individuals. |

Table 3. Summary of suggestions to optimize the doubling rate for different contexts

Conclusion

This model of DMM points out essential focal areas for practitioners who are seeking DMM. In summary, for the reader’s convenience, we have compiled some of the key practical recommendations from this article into the following list.

· Invest time in the Kingdom of God

1. Maximize time in harvest.

2. Spend time sharing the Gospel and in DBS.

3. Share the Gospel abundantly.

4. Do not depend solely on full-time workers.

· Prioritize time wisely

1. Filter to use time wisely and appropriately for each context.

2. Find connectedness in oikos, and encourage new disciples to reach their own oikos.

3. Do not give equal time to all relationships.

4. Spend enough time to be able to assess and filter for receptivity.

5. Find people with high receptivity to the Gospel and invest time in them.

6. Get to DBS asap to maximize exposure and connectedness.

7. Live out loud: self-identify as a Jesus follower early in a relationship.

· Collaborate to enhance receptivity

1. Serve the community, heal the sick, help the poor.

2. Rural: resonate with the culture.

3. Urban: listen attentively, and utilize a variety of tools.

Acknowledgements We are thankful for encouragement from Curtis Sergeant, technical discussions and support from John Hayward, and suggestions from Warrick Farrah, David Greenlee, Dave Dunaetz, and the Motus Dei network.

References

Farrah, W. (Ed.) (2021). Motus Dei: the movement of God to disciple the nations. William Carey Publishing.

Garrison, David (1999). Church planting movements. IMB.

_____ (2004). Church planting movements. WIGTake Resources.

_____ (2014). A wind in the house of Islam. WIGTake Resources.

Hayward, John (2002). A dynamic model of church growth and its application to contemporary revivals. Review of religious research. 43(3): 218-241. https://doi.org/10.2307/3512330

John, Victor & Coles, David (2021). Bhojpuri case study. In W. Farrah (Ed.), Motus Dei: the movement of God to disciple the nations. William Carey Publishing, 281-293.

Johnson, Shodankeh (2017). Passion for God, compassion for people. Mission Frontiers. Nov-Dec: 32-35.

Kebreab, Samuel (2021). Observations over 15 years of disciple making movements. In W. Farrah (Ed.), Motus Dei: the movement of God to disciple the nations. William Carey Publishing, 55-64.

Keener, C. D. (2021). Questions Jesus asked: Discovery Bible Study, available at https://1drv.ms/w/s!Ajq3KxSi6riyiAFDbPcAg5gpbEUn?e=BQDfH1.

Keener, C. D. & Foster, Dave (2025). Sister paper to be submitted for publication.

_____ (n.d.). Model of Disciple Making Movements.

https://1drv.ms/b/s!Ajq3KxSi6riyxGraTYmZLYOQ2V4y?e=Cp4mq8

Larsen, Trevor (2018). Focus on fruit: movement case studies and fruitful practices.

Lim, David S. (2021). A biblical missiology of kingdomization through Disciple Multiplication Movements of house church networks. In W. Farrah (Ed.), Motus Dei: the movement of God to disciple the nations. William Carey Publishing, 106-117.

Long, Justin (2020). 1% of the world: a macroanalysis of 1,369 movements to Christ. Mission Frontiers. 42(6), Nov/Dec: 37-42.

_____ (2023). How long to reach the goal? Movement engagements in every unreached people and place by 2025 (36 months). Mission Frontiers. 45(1), Jan/Feb: 34-37.

Pollock, Doug (2010). God space: where spiritual conversations happen naturally. Group Publishing.

Shull, Rodger. (n,d,). 2x2, oikos, and why research is important in CPMs. Accessed 3/12/2021 at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1f670FdATJ-okHfWcVlrTAOKL69baJg3Sv3AfA7mdvrA/edit?usp=sharing.

Smith, Steve & Kai, Ying (2011). T4T: a discipleship re-revolution. WIGTake Resources.

Sundell, Jeff (2016). Telling stories of hope. Mission Frontiers. 38(2), Mar/Apr; E3 Partners, accessed 8/22/2021 at

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1M4_IILSlmRF5ivsw3mVl8r9PKfjCEWfiesZSa0rAhYs/edit

Sunshine, G. S., Benoit, G. C., & Trousdale, J. (2018). The kingdom unleashed: how Jesus' 1st century kingdom values are transforming thousands of cultures and awakening his church. DMM Library. Quote of a leader named Younoussa Djao, Kindle location 2399.

Wood, Lee (2021). 7 things we’ve learned in 7 years, accessed 8/24/2021 at https://www.1body.church/7-things-weve-learned-in-seven-years/. Each of the 7 things is expanded in its own blog post.